Orbital Hybridisation from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Jump To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shapes and Structures of Organic Molecules HYBRIDISATION

Department of Chemistry Anugrah Memorial College, Gaya Class- B.Sc. 1 (Hons) Subject- Organic Chemistry Paper- 1C Unit- Shapes and Structures of Organic molecules Teacher – Dr. Nidhi Tripathi Assistant Professor Shapes and Structures of Organic molecules HYBRIDISATION The formation of bonds is no less than the act of courtship. Atoms come closer, attract to each other and gradually lose a little part of themselves to the other atoms. In chemistry, the study of bonding, that is, Hybridization is of prime importance. What happens to the atoms during bonding? What happens to the atomic orbitals? The answer lies in the concept of Hybridisation. Let us see! Introducing Hybridisation All elements around us, behave in strange yet surprising ways. The electronic configuration of these elements, along with their properties, is a unique concept to study and observe. Owing to the uniqueness of such properties and uses of an element, we are able to derive many practical applications of such elements. When it comes to the elements around us, we can observe a variety of physical properties that these elements display. The study of hybridization and how it allows the combination of various molecules in an interesting way is a very important study in science. Understanding the properties of hybridisation lets us dive into the realms of science in a way that is hard to grasp in one go but excellent to study once we get to know more about it. Let us get to know more about the process of hybridization, which will help us understand the properties of different elements. What is Hybridization? Scientist Pauling introduced the revolutionary concept of hybridization in the year 1931. -

VSEPR Theory

VSEPR Theory The valence-shell electron-pair repulsion (VSEPR) model is often used in chemistry to predict the three dimensional arrangement, or the geometry, of molecules. This model predicts the shape of a molecule by taking into account the repulsion between electron pairs. This handout will discuss how to use the VSEPR model to predict electron and molecular geometry. Here are some definitions for terms that will be used throughout this handout: Electron Domain – The region in which electrons are most likely to be found (bonding and nonbonding). A lone pair, single, double, or triple bond represents one region of an electron domain. H2O has four domains: 2 single bonds and 2 nonbonding lone pairs. Electron Domain may also be referred to as the steric number. Nonbonding Pairs Bonding Pairs Electron domain geometry - The arrangement of electron domains surrounding the central atom of a molecule or ion. Molecular geometry - The arrangement of the atoms in a molecule (The nonbonding domains are not included in the description). Bond angles (BA) - The angle between two adjacent bonds in the same atom. The bond angles are affected by all electron domains, but they only describe the angle between bonding electrons. Lewis structure - A 2-dimensional drawing that shows the bonding of a molecule’s atoms as well as lone pairs of electrons that may exist in the molecule. Provided by VSEPR Theory The Academic Center for Excellence 1 April 2019 Octet Rule – Atoms will gain, lose, or share electrons to have a full outer shell consisting of 8 electrons. When drawing Lewis structures or molecules, each atom should have an octet. -

Structures and Properties of Substances

Structures and Properties of Substances Introducing Valence-Shell Electron- Pair Repulsion (VSEPR) Theory The VSEPR theory In 1957, the chemist Ronald Gillespie and Ronald Nyholm, developed a model for predicting the shape of molecules. This model is usually abbreviated to VSEPR (pronounced “vesper”) theory: Valence Shell Electron Pair Repulsion The fundamental principle of the VSEPR theory is that the bonding pairs (BP) and lone pairs (LP) of electrons in the valence level of an atom repel one another. Thus, the orbital for each electron pair is positioned as far from the other orbitals as possible in order to achieve the lowest possible unstable structure. The effect of this positioning minimizes the forces of repulsion between electron pairs. A The VSEPR theory The repulsion is greatest between lone pairs (LP-LP). Bonding pairs (BP) are more localized between the atomic nuclei, so they spread out less than lone pairs. Therefore, the BP-BP repulsions are smaller than the LP-LP repulsions. The repulsion between a bond pair and a lone-pair (BP-LP) is intermediate between the other two. In other words, in terms of decreasing repulsion: LP-LP > LP-BP > BP-BP The tetrahedral shape around a single-bonded carbon atom (e.g. in CH4), the planar shape around a carbon atom with two double bond (e.g. in CO2), and the bent shape around an oxygen atom in H2O result from repulsions between lone pairs and/or bonding pairs of electrons. The VSEPR theory The repulsion is greatest between lone pairs (LP-LP). Bonding pairs (BP) are more localized between the atomic nuclei, so they spread out less than lone pairs. -

Chemical Bonding II: Molecular Shapes, Valence Bond Theory, and Molecular Orbital Theory Review Questions

Chemical Bonding II: Molecular Shapes, Valence Bond Theory, and Molecular Orbital Theory Review Questions 10.1 J The properties of molecules are directly related to their shape. The sensation of taste, immune response, the sense of smell, and many types of drug action all depend on shape-specific interactions between molecules and proteins. According to VSEPR theory, the repulsion between electron groups on interior atoms of a molecule determines the geometry of the molecule. The five basic electron geometries are (1) Linear, which has two electron groups. (2) Trigonal planar, which has three electron groups. (3) Tetrahedral, which has four electron groups. (4) Trigonal bipyramid, which has five electron groups. (5) Octahedral, which has six electron groups. An electron group is defined as a lone pair of electrons, a single bond, a multiple bond, or even a single electron. H—C—H 109.5= ijj^^jl (a) Linear geometry \ \ (b) Trigonal planar geometry I Tetrahedral geometry I Equatorial chlorine Axial chlorine "P—Cl: \ Trigonal bipyramidal geometry 1 I Octahedral geometry I 369 370 Chapter 10 Chemical Bonding II The electron geometry is the geometrical arrangement of the electron groups around the central atom. The molecular geometry is the geometrical arrangement of the atoms around the central atom. The electron geometry and the molecular geometry are the same when every electron group bonds two atoms together. The presence of unbonded lone-pair electrons gives a different molecular geometry and electron geometry. (a) Four electron groups give tetrahedral electron geometry, while three bonding groups and one lone pair give a trigonal pyramidal molecular geometry. -

Molecular Shape

VSEPR Theory VSEPR Theory Shapes of Molecules Molecular Structure or Molecular Geometry The 3-dimensional arrangement of the atoms that make-up a molecule. Determines several properties of a substance, including: reactivity, polarity, phase of matter, color, magnetism, and biological activity. The chemical formula has no direct relationship with the shape of the molecule. VSEPR Theory Shapes of Molecules Molecular Structure or Molecular Geometry The 3-dimensional shapes of molecules can be predicted by their Lewis structures. Valence-shell electron pair repulsion (VSEPR) model or electron domain (ED) model: Used in predicting the shapes. The electron pairs occupy a certain domain. They move as far apart as possible. Lone pairs occupy additional domains, contributing significantly to the repulsion and shape. VSEPR Theory Terms and Definitions Bonding Pairs (AX) Electron pairs that are involved in the bonding. Lone Pairs (E) – aka non-bonding pairs or unshared pairs Electrons that are not involved in the bonding. They tend to occupy a larger domain. Electron Domains (ED) Total number of pairs found in the molecule that contribute to its shape. VSEPR – Molecular Shape Multiple covalent bonds Bond Angle: around the same atom • Angle formed by any determine the shape two terminal (outside) Negative e- pairs (same atoms and a central charge) repel each other atom • Caused by the repulsion Repulsions push the pairs as far apart as possible of shared electron pairs. Hybridization What’s a hybrid? • Combining two of the same -

The Noble Gases

INTERCHAPTER K The Noble Gases When an electric discharge is passed through a noble gas, light is emitted as electronically excited noble-gas atoms decay to lower energy levels. The tubes contain helium, neon, argon, krypton, and xenon. University Science Books, ©2011. All rights reserved. www.uscibooks.com Title General Chemistry - 4th ed Author McQuarrie/Gallogy Artist George Kelvin Figure # fig. K2 (965) Date 09/02/09 Check if revision Approved K. THE NOBLE GASES K1 2 0 Nitrogen and He Air P Mg(ClO ) NaOH 4 4 2 noble gases 4.002602 1s2 O removal H O removal CO removal 10 0 2 2 2 Ne Figure K.1 A schematic illustration of the removal of O2(g), H2O(g), and CO2(g) from air. First the oxygen is removed by allowing the air to pass over phosphorus, P (s) + 5 O (g) → P O (s). 20.1797 4 2 4 10 2s22p6 The residual air is passed through anhydrous magnesium perchlorate to remove the water vapor, Mg(ClO ) (s) + 6 H O(g) → Mg(ClO ) ∙6 H O(s), and then through sodium hydroxide to remove 18 0 4 2 2 4 2 2 the carbon dioxide, NaOH(s) + CO2(g) → NaHCO3(s). The gas that remains is primarily nitrogen Ar with about 1% noble gases. 39.948 3s23p6 36 0 The Group 18 elements—helium, K-1. The Noble Gases Were Kr neon, argon, krypton, xenon, and Not Discovered until 1893 83.798 radon—are called the noble gases 2 6 4s 4p and are noteworthy for their rela- In 1893, the English physicist Lord Rayleigh noticed 54 0 tive lack of chemical reactivity. -

Hybrid Orbitals Hybrid Orbitals

Molecular Shape and Molecular Shape and Molecular Polarity Molecular Polarity • When there is a difference in electronegativity between • In water, the molecule is not linear and the bond dipoles two atoms, then the bond between them is polar. do not cancel each other. • It is possible for a molecule to contain polar bonds, but • Therefore, water is a polar molecule. not be polar. • For example, the bond dipoles in CO2 cancel each other because CO2 is linear. Figure 9.12 Prentice Hall © 2003 Chapter 9 Prentice Hall © 2003 Chapter 9 Molecular Shape and Molecular Shape and Molecular Polarity Molecular Polarity • The overall polarity of a molecule depends on its molecular geometry. Figure 9.13 Figure 9.11 Prentice Hall © 2003 Chapter 9 Prentice Hall © 2003 Chapter 9 1 Covalent Bonding and Covalent Bonding and Orbital Overlap Orbital Overlap • How do we account for shape in terms of quantum • As two nuclei approach each other their atomic orbitals mechanics? overlap. • What are the orbitals that are involved in bonding? • As the amount of overlap increases, the energy of the • We use Valence Bond Theory: interaction decreases. • Bonds form when orbitals on atoms overlap. • At some distance the minimum energy is reached. • There are two electrons of opposite spin in the orbital overlap. • The minimum energy corresponds to the bonding distance (or bond length). • As the two atoms get closer, their nuclei begin to repel and the energy increases. Prentice Hall © 2003 Chapter 9 Prentice Hall © 2003 Chapter 9 Covalent Bonding and Covalent Bonding and Orbital Overlap Orbital Overlap • At the bonding distance, the attractive forces between nuclei and electrons just balance the repulsive forces (nucleus-nucleus, electron-electron). -

Chapter 9. Molecular Geometry and Bonding Theories

Chapter 9. Molecular Geometry and Bonding Theories Media Resources Figures and Tables in Transparency Pack: Section: Figure 9.2 Shapes of AB2 and AB3 Molecules 9.1 Molecular Shapes Figure 9.3 Shapes Allowing Maximum Distances 9.1 Molecular Shapes between Atoms in ABn Molecules Table 9.1 Electron-Domain Geometries as a 9.2 VSEPR Model Function of Number of Electron Domains Table 9.2 Electron-Domain and Molecular 9.2 VSEPR Model Geometries for Two, Three, and Four Electron Domains around a Central Atom Table 9.3 Electron-Domain and Molecular 9.2 VSEPR Model Geometries for Five and Six Electron Domains around a Central Atom Figure 9.12 Polar and Nonpolar Molecules 9.3 Molecular Shape and Molecular Polarity Containing Polar Bonds Figure 9.14 Formation of the H2 Molecule as 9.4 Covalent Bonding and Orbital Overlap Atomic Orbitals Overlap Figure 9.15 Formation of sp Hybrid Orbitals 9.5 Hybrid Orbitals Figure 9.17 Formation of sp2 Hybrid Orbitals 9.5 Hybrid Orbitals Figure 9.18 Formation of sp3 Hybrid Orbitals 9.5 Hybrid Orbitals Table 9.4 Geometric Arrangements Characteristic 9.5 Hybrid Orbitals of Hybrid Orbital Sets Figure 9.23 The Orbital Structure of Ethylene 9.6 Multiple Bonds Figure 9.24 Formation of Two π Bonds in 9.6 Multiple Bonds Acetylene, C2H2 Figure 9.26 σ and the π Bond Networks in Benzene, 9.6 Multiple Bonds C6H6 Figure 9.27 Delocalized π Bonds in Benzene 9.6 Multiple Bonds Figure 9.32 The Two Molecular Orbitals of H2, One 9.7 Molecular Orbitals a Bonding MO and One an Antibonding MO Figure 9.35 Energy-level Diagram for the Li2 -

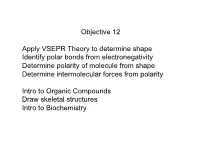

Objective 12 Apply VSEPR Theory to Determine Shape Identify Polar

Objective 12 Apply VSEPR Theory to determine shape Identify polar bonds from electronegativity Determine polarity of molecule from shape Determine intermolecular forces from polarity Intro to Organic Compounds Draw skeletal structures Intro to Biochemistry Structure ---> Shape ---> Properties, e.g., Polarity Water is the Universal Solvent What Makes a Substance Soluble in Water? Draw the structure of water. The shape of water is: a) tetrahedral b) trigonal planar c) linear d) trigonal pyramid e) bent Water is: f) Polar g) non-polar Is HCl soluble in water? Yes No Give reasons for your answer. Molecular Structure Determines Shape Which Determines Properties Shape is determined from Valence Shell Electron Pair Repulsion (VSEPR) Theory Electron pair - Like charges repel. - Where should the electron pairs be located so they are as far away from each other as possible? Central atom - Shape depends on # of e pairs around the central atom o 180 = bond angle - 2 e - - Linear shape pairs - 120o = bond angle 3 e- pairs Trigonal planar shape - - - 109o = bond angle 4 e- pairs - - Tetrahedral shape - Table 1. Shape at a Central Atom Based on VSEPR Theory # of e- # of bonding # of lone Shape Example pairs pairs pairs 2 2 0 Linear BeH2 3 3 0 Trigonal BH3 planar 4 4 0 Tetrahedral CH4 4 3 1 Trigonal NH3 pyramid 4 2 2 Bent H2O # of e- pairs = # of bonding pairs + # of lone pairs VSEPR Theory Tells You the Shape at Each Central Atom Treat a Double Bond or Triple Bond the Same as a Single Bond. E.g., ethylene = C2H4. Draw the Lewis structure. -

Shapes of Molecules and Hybridization

Shapes of Molecules and Hybridization A. Molecular Geometry • Lewis structures provide us with the number and types of bonds around a central atom, as well as any NB electron pairs. They do not tell us the 3-D structure of the molecule. H H C H CH4 as drawn conveys no 3-D information (bonds appear like they are 90° apart) H • The Valence Shell Electron Pair Repulsion Theory (VSEPR), developed in part by Ron Gillespie at McMaster in 1957, allows us to predict 3-D shape. This important Canadian innovation is found worldwide in any intro chem course. • VSEPR theory has four assumptions 1. Electrons, in pairs, are placed in the valence shell of the central atom 2. Both bonding and non-bonding (NB) pairs are included 3. Electron pairs repel each other Æ maximum separation. 4. NB pairs repel more strongly than bonding pairs, because the NB pairs are attracted to only one nucleus • To be able to use VSEPR theory to predict shapes, the molecule first needs to be drawn in its Lewis structure. Shapes of Molecules and Hybridization 2 • VSEPR theory uses the AXE notation (m and n are integers), where m + n = number of regions of electron density (sometimes also called number of charge clouds). AXmEn 1. Molecules with no NB pairs and only single bonds • We will first consider molecules that do not have multiple bonds nor NB pairs around the central atom (n = 0). • Example: BeCl2 o Molecule is linear (180°) • Example: BF3 o Molecule is trigonal (or triangular) planar (120°) Shapes of Molecules and Hybridization 3 • Example: CH4 o Molecule is tetrahedral (109.5°) • Example: PF5 o Molecule is trigonal bipyramidal (90° and 120°). -

Chemistry of Noble Gases

Prepared by: Dr. Ambika Kumar Asst. Prof. in Chemistry B. N. College Bhagalpur Contact No. 7542811733 e-mail ID: [email protected] Unit VI- Chemistry of Noble Gases The noble gases make up a group of chemical elements with similar properties; under standard conditions, they are all odorless, colorless, monatomic gases with very low chemical reactivity. The six naturally occurring noble gases are helium, neon, argon, krypton, xenon, and the radioactive radon. Chemistry of Xenon (Xe) Xenon (Xe), chemical element, a heavy and extremely rare gas of Group 18 (noble gases) of the periodic table. It was the first noble gas found to form true chemical compounds. More than 4.5 times heavier than air, xenon is colourless, odourless, and tasteless. Solid xenon belongs to the face-centred cubic crystal system, which implies that its molecules, which consist of single atoms, behave as spheres packed together as closely as possible. The name xenon is derived from the Greek word xenos, “strange” or “foreign.” Compounds of Xenon Not all the noble gases combine with oxygen and fluorine. Only the heavier noble gases like Xe (larger atomic radius) will react with oxygen and fluorine. Noble gas form compounds with oxygen and fluorine only because they are most electronegative elements. So they can ionise Xenon easily. 1.Xenon Fluorides: Xenon forms three fluorides, XeF2, XeF4 and XeF6. These can be obtained by the direct interaction between xenon and fluorine under appropriate experimental conditions, XeF2, XeF4 and XeF6 are colourless crystalline solids and sublime readily at 298 K. They are powerful fluorinating agents. -

Valence Bond Theory: Hybridization

Exercise 13 Page 1 Illinois Central College CHEMISTRY 130 Name:___________________________ Laboratory Section: _______ Valence Bond Theory: Hybridization Objectives To illustrate the distribution of electrons and rearrangement of orbitals in covalent bonding. Background Hybridization: In the formation of covalent bonds, electron orbitals overlap in order to form "molecular" orbitals, that is, those that contain the shared electrons that make up a covalent bond. Although the idea of orbital overlap allows us to understand the formation of covalent bonds, it is not always simple to apply this idea to polyatomic molecules. The observed geometries of polyatomic molecules implies that the original "atomic orbitals" on each of the atoms actually change their shape, or "hybridize" during the formation of covalent bonds. But before we can look at how the orbitals actually "reshape" themselves in order to form stable covalent bonds, we must look at the two mechanisms by which orbitals can overlap. Sigma and Pi bonding Two orbitals can overlap in such a way that the highest electron "traffic" is directly between the two nuclei involved; in other words, "head-on". This head-on overlap of orbitals is referred to as a sigma bond. Examples include the overlap of two "dumbbell" shaped "p" orbitals (Fig.1) or the overlap of a "p" orbital and a spherical "s" orbital (Fig. 2). In each case, the highest region of electron density lies along the "internuclear axis", that is, the line connecting the two nuclei. o o o o o o "p" orbital "p" orbital sigma bond "s" orbital "p" orbital sigma bond Sigma Bonding Sigma Bonding Figure 1.