The Qualies and the 2009 US Open

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WTT . . . at a Glance

WTT . At a glance World TeamTennis Pro League presented by Advanta Dates: July 5-25, 2007 (regular season) Finals: July 27-29, 2007 – WTT Championship Weekend in Roseville, Calif. July 27 & 28 – Conference Championship matches July 29 – WTT Finals What: 11 co-ed teams comprised of professional tennis players and a coach. Where: Boston Lobsters................ Boston, Mass. Delaware Smash.............. Wilmington, Del. Houston Wranglers ........... Houston, Texas Kansas City Explorers....... Kansas City, Mo. Newport Beach Breakers.. Newport Beach, Calif. New York Buzz ................. Schenectady, N.Y. New York Sportimes ......... Mamaroneck, N.Y. Philadelphia Freedoms ..... Radnor, Pa. Sacramento Capitals.........Roseville, Calif. St. Louis Aces................... St. Louis, Mo. Springfield Lasers............. Springfield, Mo. Defending Champions: The Philadelphia Freedoms outlasted the Newport Beach Breakers 21-14 to win the King Trophy at the 2006 WTT Finals in Newport Beach, Calif. Format: Each team is comprised of two men, two women and a coach. Team matches consist of five events, with one set each of men's singles, women's singles, men's doubles, women's doubles and mixed doubles. The first team to reach five games wins each set. A nine-point tiebreaker is played if a set reaches four all. One point is awarded for each game won. If necessary, Overtime and a Supertiebreaker are played to determine the outright winner of the match. Live scoring: Live scoring from all WTT matches featured on WTT.com. Sponsors: Advanta is the presenting sponsor of the WTT Pro League and the official business credit card of WTT. Official sponsors of the WTT Pro League also include Bälle de Mätch, FirmGreen, Gatorade, Geico and Wilson Racquet Sports. -

Additional Players to Watch Players to Watch

USTA PRO CIRCUIT PLAYER INFORMATION PLAYERS TO WATCH Prakash Amritraj (IND) pg. 2 Kevin Kim pg. 6 Kevin Anderson (RSA) Evan King Carsten Ball (AUS) Austin Krajicek Brian Battistone Alex Kuznetsov Dann Battistone Jesse Levine Alex Bogomolov Jr. pg. 3 Michael McClune pg. 7 Devin Britton Nicholas Monroe Chase Buchanan Wayne Odesnik Lester Cook Rajeev Ram Ryler DeHeart Bobby Reynolds Amer Delic pg. 4 Michael Russell pg. 8 Taylor Dent Tim Smyczek Somdev Devvarman (IND) Vince Spadea Alexander Domijan Blake Strode Brendan Evans Ryan Sweeting Jan-Michael Gambill pg. 5 Bernard Tomic (AUS) pg. 9 Robby Ginepri Michael Venus Ryan Harrison Jesse Witten Scoville Jenkins Michael Yani Robert Kendrick Donald Young ADDITIONAL PLAYERS TO WATCH Jean-Yves Aubone pg. 10 Nick Lindahl (AUS) pg. 12 Sekou Bangoura Eric Nunez Stephen Bass Greg Ouellette Yuki Bhambri (IND) Nathan Pasha Alex Clayton Todd Paul Jordan Cox Conor Pollock Benedikt Dorsch (GER) Robbye Poole Adam El Mihdawy Tennys Sandgren Mitchell Frank Raymond Sarmiento Bjorn Fratangelo Nate Schnugg Marcus Fugate pg. 11 Holden Seguso pg. 13 Chris Guccione (AUS) Phillip Simmonds Jarmere Jenkins John-Patrick Smith Steve Johnson Jack Sock Roy Kalmanovich Ryan Thacher Bradley Klahn Nathan Thompson Justin Kronauge Ty Trombetta Nikita Kryvonos Kaes Van’t Hof Denis Kudla Todd Widom Harel Levy (ISR) Dennis Zivkovic ** All players American unless otherwise noted. * All information as of February 1, 2010 P L A Y E R S T O W A T C H Prakash Amritraj (IND) Age: 26 (10/2/83) Hometown: Encino, Calif. 2009 year-end ranking: 215 Amritraj represents India in Davis Cup but has strong ties—with strong results—in the United States. -

Tournament Notes

TournamenT noTes as of may 31, 2010 2010 RECOATING WEST INC. USTA MEN’S $15,000 PRO TENNIS TOURNAMENT LOOMIS, CA• JUNE 5-13 USTA PRO CIRCUIT RETURNS TO LOOMIS TournamenT InFormaTIon The 2010 Recoating West Inc. USTA Men’s $15,000 Pro Tennis Tournament enters its USTA Site: Del Oro High School – Loomis, Calif. fourth year on the USTA Pro Circuit and is one of Websites: www.rwiprocircuit.org six Futures events hosted in California. Loomis kicks off three consecutive USTA Pro Circuit procircuit.usta.com hard court tournaments in California (Davis is Qualifying draw begins: Saturday, June 5 held next week, followed by Chico) to prepare players for the summer hard court season. Main draw begins: Tuesday, June 8 Main Draw: 32 Singles / 16 Doubles This year’s main draw includes tour veteran Vince Spadea, a two-time Olympian who Surface: Hard / Outdoor peaked at No. 18 in the world in 2005, beat Rising young American Alex Domijan was the Prize Money: $15,000 Andre Agassi to reach the quarterfinals of the No. 1-ranked USTA Boys’ 18s junior for much 1999 Australian Open and got to the fourth of 2009. Tournament Director: round at the US Open in 1995 and 1999; Monty Basnyat, (916) 316-7577 last year’s singles runner-up, Russia’s Artem [email protected] Sitak, who defeated former world No. 7 Mario Players expected in qualifying include: Sekou Bangoura, 18, who just completed his Tournament Press Contact: Ancic to win the $15,000 Futures in McAllen, Texas, in March; Greg Ouellette, a four-time freshman year at the University of Florida and, Allison Miller, (916) 813-7719 All-American for the University of Florida who in juniors, reached the singles final at the 2009 [email protected] peaked at No. -

AEGON OPEN NOTTINGHAM: DAY 2 MEDIA NOTES Monday, June 20, 2016

AEGON OPEN NOTTINGHAM: DAY 2 MEDIA NOTES Monday, June 20, 2016 Nottingham Tennis Centre, Nottingham, Great Britain | June 19-25, 2016 Draw: S-48, D-16 | Prize Money: €648,255 | Surface: Grass ATP World Tour Info Tournament Info ATP PR & Marketing www.ATPWorldTour.com www.lta.org.uk Mark Epps: [email protected] Twitter: @ATPWorldTour Twitter: @BritishTennis #AegonOpen Press Room: +44 333 011 1030 Facebook: ATP World Tour Facebook: British Tennis REIGNING CHAMPION ISTOMIN, BRITISH TRIO HEADLINE CENTRE COURT DAY 2 PREVIEW: The remaining 13 first round singles matches and one second round contest are on Monday’s schedule at the Aegon Open Nottingham. Reigning champion Denis Istomin and three British players are on Centre Court. First up is a continuation of Sunday’s match between Russians Mikhail Youzhny and Teymuraz Gabashvili, who leads the head-to-head meetings 2-1. Gabashvili, who is up 6-4, 3-3 in the match, has won the last two meetings, in 2008 Moscow and 2009 Zagreb. In the next match on, Malek Jaziri of Tunisia and wild card James Ward meet for the second time. Ward won the previous meeting 8-6 in the fifth set in a Davis Cup tie in 2011. Jaziri is playing in Nottingham for the second straight year.while Ward is looking for his first ATP World Tour win of the season (0-1). Ward’s best Aegon Open result is the quarter-finals in 2010. In the third match on, Lukas Rosol and British No. 3 Kyle Edmund square off for the second time. Edmund won the previous meeting in two tie-breaks in Bucharest in April. -

Take the Road to Success

B10 Thursday, April 12, 2007 Old Gold & Black Sports Baseball: Deacs go on five-game win streak, top Costal Carolina Continued from Page B1 As in the previous day, the Deacs saidd pitching coach Greg Bauer. “But One day later, Hunter made his first all the way to third base off a throwing er- jumped on the scoreboard early, as they it’s just exciting for our guys to have Wake Forest start as the Deacs defeated ror by the Chanticleers center fielder. scored all seven of their runs in the first their leader back.” Coastal Carolina 4-3 April 11. Costal Carolina managed to score an- innings. “It’s nice to put some things three innings. Returning home The Deacs got off to a good start, scor- other run in the sixth inning, but were together and get these wins,” junior Goff again keyed Wake Forest’s of- April 10, Wake ing a run in the first inning, when fresh- unable to overtake the Deacs, giving the outfielder Ben Terry said. fensive attack with a pair of hits and a overcame an early man catcher Michael Murray’s single to Deacs a 4-3 win and moving them to “We just have to carry this momentum pair of RBIs. deficit to demolish center field drove in Linnekohl. 20-16 on the season. and keep the bats and pitching going to Senior catcher Dan Rosaia and sopho- UNC-Greensboro Wake Forest held the Chanticleers “We’ve switched up the rotation a bit get these wins.” more shortstop Dustin Hood also col- by a final score of scoreless in the first two innings of play, and moved (junior fireballer Eric) Niesen The final game in the series on April lected two hits each. -

Tournament Notes

TOURNAMENT NOTES as of April 21, 2016 BOYD TINSLEY CLAY COURT CLASSIC CHARLOTTESVILLE, VA • APRIL 24-MAY 1 USTA PRO CIRCUIT WOMEN’S TENNIS RETURNS TO CHARLOTTESVILLE FOR 15TH YEAR, CONTINUES USTA PRO CIRCUIT ROLAND GARROS WILD CARD CHALLENGE The Boyd Tinsley Clay Court Classic returns to TOURNAMENT Charlottesville for the 15th consecutive year. INFORMATION It is the only USTA Pro Circuit women’s event held in Virginia. Charlottesville also hosts a Ryan USTA/Steven Site: Boar’s Head Sports Club $50,000 USTA Pro Circuit men’s Challenger in Charlottesville, Va. early November and, for the first time, will host a $25,000 men’s event in June to kick off the Websites: www.boarsheadinn.com new USTA Pro Circuit Collegiate Series. procircuit.usta.com Qualifying Draw Begins: Sunday, April 24 Charlottesville is also one of three consecutive women’s clay-court tournaments (joining last Main Draw Begins: Tuesday, April 26 week’s $50,000 event in Dothan, Ala., and Main Draw: 32 Singles / 16 Doubles next week’s $75,000 event in Indian Harbour Beach, Fla.) that are part of the USTA Pro Surface: Clay / Outdoor Circuit Roland Garros Wild Card Challenge, Prize Money: $50,000 which will award a men’s and women’s wild card into the 2016 French Open. Along with Tournament Director: these three women’s tournaments, the men’s Top seed and 2013 Charlottesville singles champion Shelby Rogers advanced to the third Ron Manilla, (434) 960-3364 tournaments that are part of the challenge round at the 2015 US Open as a qualifier. -

Return of Organization Exempt from Income

l efile GRAPHIC p rint - DO NOT PROCESS As Filed Data - DLN: 93490321002056 Return of Organization Exempt From Income Tax OMB No 1545-0047 Form 990 Under section 501 (c), 527, or 4947( a)(1) of the Internal Revenue Code ( except black lung benefit trust or private foundation) 2 00 5_ Department of the Open -The organization may have to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements Treasury Inspection Internal Revenue Service A For the 2005 calendar year, or tax year beginning 01 -01-2005 and ending 12 -31-2005 C Name of organization D Employer identification number B Check if applicable Please United States Tennis Association Inc 13-5459420 1 Address change use IRS l a b el or Number and street (or P 0 box if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite F Name change print or type. See 70 West Red Oak Lane 1 Initial return Specific E Telep hone number Instruc - City or town, state or country, and ZIP + 4 (914) 696-7100 F_ Final return tions . White Plains, NY 10604 (- Amended return F_ Application pending fl Other ( specify) * Section 501(c)(3) organizations and 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable H and I are not applicable to section 527 organizations trusts must attach a completed Schedule A (Form 990 or 990-EZ). H(a) Is this a group return for affiliates? F Yes F No H(b) If "Yes" enter number of affiliates 0- G Web site: - www usta com H(c) Are all affiliates included? F Yes F No 3 Organization type (check only one) 1- F 501(c) (6) -4 (insert no ) (- 4947(a)(1) or F_ 527 (If "No," attach a list See instructions ) H(d) Is this a separate return filed by an organization K Check here - 1 if the organization's gross receipts are normally not more than $25,000 The covered by a group ruling? (- Yes F No organization need not file a return with the IRS, but if the organization received a Form 990 Package in the mail, it should file a return without financial data Some states require a complete return. -

P17 Layout 1

TUESDAY, JANUARY 14, 2014 SPORTS Islanders dump Stars DALLAS: John Tavares scored with 1:24 to is tied in points with Washington for sec- go and Brock Nelson added an empty-net- ond place in the Metropolitan Division - ter, leading the streaking New York one ahead of Philadelphia. Islanders to a 4-2 victory over the slumping The Rangers have won seven straight Dallas Stars on Sunday. against the Flyers at home, outscoring Kyle Okposo had two goals in New them 28-8. Ray Emery rebounded after the York’s fourth consecutive victory. The rough first period and finished with 31 Islanders (18-22-7) also have won seven saves for the Flyers. Lundqvist lost his straight road games. shutout bid when Mark Streit scored a The Islanders rallied past the Stars after power-play goal 6:49 into the third. trailing 2-0 after one period for the second time in a week. This time, New York scored BLACKHAWKS 5, OILERS 3 three goals in the final 4:16. Dallas (20-18-7) Marian Hossa had a power-play goal has lost six in a row for the first time since and an assist as Chicago beat Edmonton to March 2011. Ray Whitney and Sergei end a three-game losing streak. Gonchar scored first-period goals for the Ben Smith, Andrew Shaw, Jonathan Stars against goalie Kevin Poulin, who fin- Toews and Brent Seabrook also scored for ished with 29 saves. Dallas goaltender Dan Chicago, which had 15 goals against Ellis stopped 27 shots. Edmonton in a three-game sweep of the season series. -

Brisbane International 2013 ORDER of PLAY Sunday, 30 December 2012

Brisbane International 2013 ORDER OF PLAY Sunday, 30 December 2012 PAT RAFTER ARENA SHOW COURT 1 SHOW COURT 2 COURT 10 COURT 14 Starting At: 11:30 am Starting At: 11:00 am Starting At: 10:30 am Starting At: 10:30 am Starting At: 10:30 am WTA ATP WTA WTA Urszula RADWANSKA (POL) Donald YOUNG (USA) [WC] Bojana BOBUSIC (AUS) Monica PUIG (PUR) 1 vs vs vs vs Tamira PASZEK (AUT) Mischa ZVEREV (GER) Kristyna PLISKOVA (CZE) Bethanie MATTEK-SANDS (USA) Starting At: 11:30 am followed by followed by followed by followed by WTA WTA ATP WTA WTA Roberta VINCI (ITA) Lucie HRADECKA (CZE) John MILLMAN (AUS) Lesia TSURENKO (UKR) Vania KING (USA) 2 vs vs vs vs vs [WC] Jarmila GAJDOSOVA (AUS) Anastasia PAVLYUCHENKOVA (RUS) Alex BOGOMOLOV JR. (RUS) Olga PUCHKOVA (RUS) Ksenia PERVAK (KAZ) followed by followed by followed by followed by followed by WTA WTA ATP ATP ATP Gilles MULLER (LUX) or Petra KVITOVA (CZE) [6] Daniela HANTUCHOVA (SVK) Igor KUNITSYN (RUS) Denis KUDLA (USA) Jesse LEVINE (USA) 3 vs vs vs vs vs Carla SUAREZ NAVARRO (ESP) Lourdes DOMINGUEZ LINO (ESP) James DUCKWORTH (AUS) Ricardas BERANKIS (LTU) Frank DANCEVIC (CAN) followed by Not Before 2:00 PM followed by followed by followed by WTA ATP ATP ATP ATP Grigor DIMITROV (BUL) Serena WILLIAMS (USA) [3] Kei NISHIKORI (JPN) Ryan HARRISON (USA) Hiroki MORIYA (JPN) Ivo MINAR (CZE) 4 vs vs vs vs vs Varvara LEPCHENKO (USA) Mikhail ELGIN (RUS) Bastian KNITTEL (GER) Steve JOHNSON (USA) Di WU (CHN) Denis ISTOMIN (UZB) [4] Not Before 2:00 PM ATP Eric BUTORAC (USA) Paul HANLEY (AUS) [1] 5 vs [WC] Chris GUCCIONE -

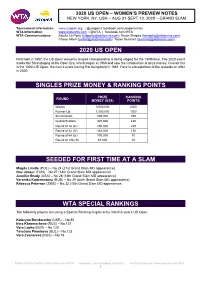

2020 Us Open Singles Prize Money & Ranking Points

2020 US OPEN – WOMEN’S PREVIEW NOTES NEW YORK, NY, USA – AUG 31-SEPT 13, 2020 – GRAND SLAM Tournament Information: www.usopen.org | @usopen | facebook.com/usopentennis WTA Information: www.wtatennis.com | @WTA | facebook.com/WTA WTA Communications: Estelle La Porte ([email protected]), Bryan Shapiro ([email protected]), Chase Altieri ([email protected]), Teyva Sammet ([email protected]) 2020 US OPEN First held in 1887, the US Open women’s singles championship is being staged for the 134th time. The 2020 event marks the 53rd staging of the Open Era, which began in 1968 and saw the introduction of prize money. Overall this is the 140th US Open, the men’s event having first being held in 1881. Here is a breakdown of the rewards on offer in 2020: SINGLES PRIZE MONEY & RANKING POINTS PRIZE RANKING ROUND MONEY (US$) POINTS Winner 3,000,000 2000 Runner-Up 1,500,000 1300 Semifinalists 800,000 780 Quarterfinalists 425,000 430 Round of 16 (4r) 250,000 240 Round of 32 (3r) 163,000 130 Round of 64 (2r) 100,000 70 Round of 128 (1r) 61,000 10 SEEDED FOR FIRST TIME AT A SLAM Magda Linette (POL) – No.24 (21st Grand Slam MD appearance) Ons Jabeur (TUN) – No.27 (14th Grand Slam MD appearance) Jennifer Brady (USA) – No.28 (13th Grand Slam MD appearance) Veronika Kudermetova (RUS) – No.29 (sixth Grand Slam MD appearance) Rebecca Peterson (SWE) – No.32 (10th Grand Slam MD appearance) WTA SPECIAL RANKINGS The following players are using a Special Ranking to gain entry into this year’s US Open: Kateryna Bondarenko (UKR) – No.85 Irina Khromacheva (RUS) – No.137 Vera Lapko (BLR) – No.120 Tsvetana Pironkova (BUL) – No.123 Vera Zvonareva (RUS) – No.78 Follow WTA on Twitter: www.twitter.com/WTA Facebook: www.facebook.com/WTA YouTube Channel: www.youtube.com/WTA 1 2020 US OPEN – WOMEN’S PREVIEW NOTES NEW YORK, NY, USA – AUG 31-SEPT 13, 2020 – GRAND SLAM ACTIVE GRAND SLAM CHAMPIONS The 2020 season has already welcomed one new Grand Slam champion: Sofia Kenin won her maiden Grand Slam singles title at Melbourne Park in January, defeating Garbiñe Muguruza in the final. -

United States Vs. Czech Republic

United States vs. Czech Republic Fed Cup by BNP Paribas 2017 World Group Semifinal Saddlebrook Resort Tampa Bay, Florida * April 22-23 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREVIEW NOTES PLAYER BIOGRAPHIES (U.S. AND CZECH REPUBLIC) U.S. FED CUP TEAM RECORDS U.S. FED CUP INDIVIDUAL RECORDS ALL-TIME U.S. FED CUP TIES RELEASES/TRANSCRIPTS 2017 World Group (8 nations) First Round Semifinals Final February 11-12 April 22-23 November 11-12 Czech Republic at Ostrava, Czech Republic Czech Republic, 3-2 Spain at Tampa Bay, Florida USA at Maui, Hawaii USA, 4-0 Germany Champion Nation Belarus at Minsk, Belarus Belarus, 4-1 Netherlands at Minsk, Belarus Switzerland at Geneva, Switzerland Switzerland, 4-1 France United States vs. Czech Republic Fed Cup by BNP Paribas 2017 World Group Semifinal Saddlebrook Resort Tampa Bay, Florida * April 22-23 For more information, contact: Amanda Korba, (914) 325-3751, [email protected] PREVIEW NOTES The United States will face the Czech Republic in the 2017 Fed Cup by BNP Paribas World Group Semifinal. The best-of-five match series will take place on an outdoor clay court at Saddlebrook Resort in Tampa Bay. The United States is competing in its first Fed Cup Semifinal since 2010. Captain Rinaldi named 2017 Australian Open semifinalist and world No. 24 CoCo Vandeweghe, No. 36 Lauren Davis, No. 49 Shelby Rogers, and world No. 1 doubles player and 2017 Australian Open women’s doubles champion Bethanie Mattek-Sands to the U.S. team. Vandeweghe, Rogers, and Mattek- Sands were all part of the team that swept Germany, 4-0, earlier this year in Maui. -

Media Guide Template

THE US OPEN T O Throughout its 133-year history, the US Open has dared its entrants to dream U R I N big, to strive for excellence in each and every match, and in turn the Open has N F A O done the same. It has moved from the West Side Tennis Club in Forest Hills to the M USTA Billie Jean King National Tennis Center, one of the largest public tennis facili - E N ties in the world, and plays its marquee matches in Arthur Ashe Stadium, the T largest tennis stadium in the world. Over the years, the US Open has drawn inspiration from tennis heroes such as Billie Jean King and Arthur Ashe, as well as the innumerable world-class players who have taken part in the event and, of course, from the hundreds of thousands of fans whose dedication to the sport and the F G A event have made the US Open a true sports and entertainment spectacular. In fact, more than R C O I L 700,000 fans on-site make the US Open the world’s largest-attended annual sporting event, and U I T N more than 53 million online visitors plus a global television audience share in the thrill and excite - Y D & ment each year. S Starting with Arthur Ashe Kids’ Day—the world's largest single-day, grass-roots tennis and entertainment event—straight through Finals Weekend, the US Open honors its future and its past, celebrating those who have made the tournament what it is today while also focusing on the next generation that will write tennis history well into the coming decades.