A Historic Context for the Archaeology of Industrial Labor in the State Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Title 26 Department of the Environment, Subtitle 08 Water

Presented below are water quality standards that are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. EPA is posting these standards as a convenience to users and has made a reasonable effort to assure their accuracy. Additionally, EPA has made a reasonable effort to identify parts of the standards that are not approved, disapproved, or are otherwise not in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. Title 26 DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT Subtitle 08 WATER POLLUTION Chapters 01-10 2 26.08.01.00 Title 26 DEPARTMENT OF THE ENVIRONMENT Subtitle 08 WATER POLLUTION Chapter 01 General Authority: Environment Article, §§9-313—9-316, 9-319, 9-320, 9-325, 9-327, and 9-328, Annotated Code of Maryland 3 26.08.01.01 .01 Definitions. A. General. (1) The following definitions describe the meaning of terms used in the water quality and water pollution control regulations of the Department of the Environment (COMAR 26.08.01—26.08.04). (2) The terms "discharge", "discharge permit", "disposal system", "effluent limitation", "industrial user", "national pollutant discharge elimination system", "person", "pollutant", "pollution", "publicly owned treatment works", and "waters of this State" are defined in the Environment Article, §§1-101, 9-101, and 9-301, Annotated Code of Maryland. The definitions for these terms are provided below as a convenience, but persons affected by the Department's water quality and water pollution control regulations should be aware that these definitions are subject to amendment by the General Assembly. B. Terms Defined. (1) "Acute toxicity" means the capacity or potential of a substance to cause the onset of deleterious effects in living organisms over a short-term exposure as determined by the Department. -

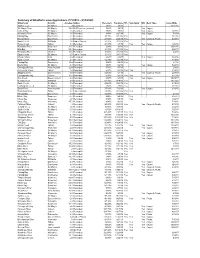

Summary of Lease Applications 9-23-20.Xlsx

Summary of Shellfish Lease Applications (1/1/2015 - 9/23/2020) Waterbody County AcreageStatus Received CompleteTFL Sanctuary WC Gear Type IssuedDate Smith Creek St. Mary's 3 Recorded 1/6/15 1/6/15 11/21/16 St. Marys River St. Mary's 16.2 GISRescreen (revised) 1/6/15 1/6/15 Yes Cages Calvert Bay St. Mary's 2.5Recorded 1/6/15 1/6/15 YesCages 2/28/17 Wicomico River St. Mary's 4.5Recorded 1/8/15 1/27/15 YesCages 5/8/19 Fishing Bay Dorchester 6.1 Recorded 1/12/15 1/12/15 Yes 11/2/15 Honga River Dorchester 14Recorded 2/10/15 2/26/15Yes YesCages & Floats 6/27/18 Smith Creek St Mary's 2.6 Under Protest 2/12/15 2/12/15 Yes Harris Creek Talbot 4.1Recorded 2/19/15 4/7/15 Yes YesCages 4/28/16 Wicomico River Somerset 26.7Recorded 3/3/15 3/3/15Yes 10/20/16 Ellis Bay Wicomico 69.9Recorded 3/19/15 3/19/15Yes 9/20/17 Wicomico River Charles 13.8Recorded 3/30/15 3/30/15Yes 2/4/16 Smith Creek St. Mary's 1.7 Under Protest 3/31/15 3/31/15 Yes Chester River Kent 4.9Recorded 4/6/15 4/9/15 YesCages 8/23/16 Smith Creek St. Mary's 2.1 Recorded 4/23/15 4/23/15 Yes 9/19/16 Fishing Bay Dorchester 12.4Recorded 5/4/15 6/4/15Yes 6/1/16 Breton Bay St. -

Maryland's Wildland Preservation System “The Best of the Best”

Maryland’s Wildland Preservation System “The“The Best Best ofof thethe Best” Best” What is a Wildland? Natural Resources Article §5‐1201(d): “Wildlands” means limited areas of [State‐owned] land or water which have •Retained their wilderness character, although not necessarily completely natural and undisturbed, or •Have rare or vanishing species of plant or animal life, or • Similar features of interest worthy of preservation for use of present and future residents of the State. •This may include unique ecological, geological, scenic, and contemplative recreational areas on State lands. Why Protect Wildlands? •They are Maryland’s “Last Great Places” •They represent much of the richness & diversity of Maryland’s Natural Heritage •Once lost, they can not be replaced •In using and conserving our State’s natural resources, the one characteristic more essential than any other is foresight What is Permitted? • Activities which are consistent with the protection of the wildland character of the area, such as hiking, canoeing, kayaking, rafting, hunting, fishing, & trapping • Activities necessary to protect the area from fire, animals, insects, disease, & erosion (evaluated on a case‐by case basis) What is Prohibited? Activities which are inconsistent with the protection of the wildland character of the area: permanent roads structures installations commercial enterprises introduction of non‐native wildlife mineral extraction Candidate Wildlands •23 areas •21,890 acres •9 new •13,128 acres •14 expansions Map can be found online at: http://dnr.maryland.gov/land/stewardship/pdfs/wildland_map.pdf -

Camping Places (Campsites and Cabins) with Carderock Springs As

Camping places (campsites and cabins) With Carderock Springs as the center of the universe, here are a variety of camping locations in Maryland, Virginia, Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Delaware. A big round of applause to Carderock’s Eric Nothman for putting this list together, doing a lot of research so the rest of us can spend more time camping! CAMPING in Maryland 1) Marsden Tract - 5 mins - (National Park Service) - C&O canal Mile 11 (1/2 mile above Carderock) three beautiful group campsites on the Potomac. Reservations/permit required. Max 20 to 30 people each. C&O canal - hiker/biker campsites (no permit needed - all are free!) about every five miles starting from Swains Lock to Cumberland. Campsites all the way to Paw Paw, WV (about 23 sites) are within 2 hrs drive. Three private campgrounds (along the canal) have cabins. Some sections could be traveled by canoe on the Potomac (canoe camping). Closest: Swains Lock - 10 mins - 5 individual tent only sites (one isolated - take path up river) - all close to parking lot. First come/first serve only. Parking fills up on weekends by 8am. Group Campsites are located at McCoy's Ferry, Fifteen Mile Creek, Paw Paw Tunnel, and Spring Gap. They are $20 per site, per night with a maximum of 35 people. Six restored Lock-houses - (several within a few miles of Carderock) - C&O Canal Trust manages six restored Canal Lock-houses for nightly rental (some with heat, water, A/C). 2) Cabin John Regional Park - 10 mins - 7 primitive walk-in sites. Pit toilets, running water. -

Countywide Park Trails Plan Amendment

MCPB Item #______ Date: 9/29/16 MEMORANDUM DATE: September 22, 2016 TO: Montgomery County Planning Board VIA: Michael F. Riley, Director of Parks Mitra Pedoeem, Deputy Director, Administration Dr. John E. Hench, Ph.D., Chief, Park Planning and Stewardship Division (PPSD) FROM: Charles S. Kines, AICP, Planner Coordinator (PPSD) Brooke Farquhar, Supervisor (PPSD) SUBJECT: Worksession #3, Countywide Park Trails Plan Amendment Recommended Planning Board Action Review, approve and adopt the plan amendment to be titled 2016 Countywide Park Trails Plan. (Attachment 1) Changes Made Since Public Hearing Draft Attached is the final draft of the plan amendment, including all Planning Board-requested changes from worksessions #1 and #2, as well as all appendices. Please focus your attention on the following pages and issues: 1. Page 34, added language to clarify the addition of the Northwest Branch Trail to the plan, in order to facilitate mountain biking access between US 29 (Colesville Rd) and Wheaton Regional Park. In addition, an errata sheet will be inserted in the Rachel Carson Trail Corridor Plan to reflect this change in policy. 2. Page 48, incorporating Planning Board-approved text from worksession #2, regarding policy for trail user types 3. Appendices 5, 6, 8, 10, 11 and 15. In addition, all maps now accurately reflect Planning Board direction. Trail Planning Work Program – Remainder of FY 17 Following the approval and adoption of this plan amendment, trail planning staff will perform the following tasks to implement the Plan and address other trail planning topics requested by the Planning Board: 1. Develop program of requirements for the top implementation priority for both natural and hard surface trails. -

5041 Nicholson Lane Rockville, Md 20852

FOR SALE | RETAIL BUILDING WITH DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY 5041 NICHOLSON LANE ROCKVILLE, MD 20852 Charles Mann Ken Traenkle 1821 Michael Faraday Drive, Suite 208 703.435.4007 x116 703.435.4007 x102 Reston, VA 20190 [email protected] [email protected] 703.435.4007 veritycommercial.com FOR SALE | RETAIL BUILDING WITH DEVELOPMENT OPPORTUNITY 5041 NICHOLSON LANE | ROCKVILLE, MD TABLE OF CONTENTS CONTENTS CONFIDENTIALITY & DISCLAIMER COVER PAGE 1 All materials and information received or derived from Verity Commercial its directors, officers, agents, TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 advisors, affiliates and/or any third party sources are provided without representation or warranty as to PROPERTY INFORMATION 3 completeness , veracity, or accuracy, condition of the property, compliance or lack of compliance with EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 applicable governmental requirements, developability or suitability, financial performance of the property, projected financial performance of the property for any party’s intended use or any and all other PROPERTY & DEVELOPMENT 5 OVERVIEW matters. LOCATION INFORMATION 6 Neither Verity Commercial its directors, officers, agents, advisors, or affiliates makes any representation or LOCATION MAP 7 warranty, express or implied, as to accuracy or completeness of the any materials or information AERIAL MAP 8 provided, derived, or received. Materials and information from any source, whether written or verbal, that DEMOGRAPHICS 9 may be furnished for review are not a substitute for a party’s active conduct of its own due diligence to DEMOGRAPHICS MAP & REPORT 10 determine these and other matters of significance to such party. Verity Commercial will not investigate or WITHIN 3 MILE DEMOGRAPHICS 11 verify any such matters or conduct due diligence for a party unless otherwise agreed in writing. -

Renovation of a Historic Burr Arch Timber Truss Bridge

January 2018 MdQI Award Winning Project: Renovation of a Historic Burr Arch Timber Truss Bridge Presenters: Keith Duerling, P.E., Baltimore County Department of Public Works Megan Peal, P.E., Wallace Montgomery Jericho Road Covered Bridge over Little Gunpowder Falls • Actual Cost: $1.54 Million • Designer: Wallace Montgomery • Contractor: Kinsley Construction/Barns & Bridges of New England • Owners: Baltimore & Harford Counties (MD) Agenda • Introduction and Background • Purpose and Need • Design • Construction • Conclusions • Best Practices Location of the Structure • Owned by Baltimore and Harford Counties • Located within Harford County Gunpowder Falls State Park Jerusalem Mill Village Jericho Road Covered Bridge Baltimore County Structure Description • Length = 86’-0” • Clear Roadway = 13’-0” • ADT = 700 Vehicles • Vertical Clearance = 12’-0” • Added to National Register of Historic Places in 1978 Theodore Burr, Drawing from US Patent No. 2,769X, April 3, 1817 History of the Structure • Timber Burr Arch Truss Constructed circa 1865 • Timber Evaluation Suggests a Major Rehabilitation Completed around 1900 Jericho Road Covered Bridge circa 1936 • Rehabilitation in 1937 • Metal Tie-rods • New Deck and Siding • Rehabilitation in 1982 • Steel Beams to Support Timber Deck • New Roof • Masonry Repairs • Localized Truss and Arch Repairs National Park Service, Historic American Building Survey MD-12, 1936 Purpose and Need • Deterioration of Existing Structure • BSR 48.5% • Deck, Superstructure and Substructure had condition ratings of 6 (Satisfactory) -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form 1

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) Exp. 10-31-84 HA-1745 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NFS use only National Register of Historic Places received JUL20I987 Inventory Nomination Form date entered*; | O OA j() See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections_______________ 1. Name historic Jerusalem Mill Village_ and or common Jerusalem Mill Village 2. Location street & number Jerusalem and Jericho roads N/A not for publication city, town Jerusalem N/A vicinity of First Congressional District state Maryland code 24 county Harford code 025 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use * district public X occupied agriculture museum building(s) private unoccupied commercial park structure X both work in progress educational X private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process yes: restricted government scientific being considered _X... yes: unrestricted industrial transportation X not applicable no military Other: 4. Owner of Property name multiple public and private (see attached list) street & number city, town vicinity of state 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Harford County Courthouse street & number Main Street Bel Air state Maryland city, town 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Maryland Historical Trust title Historic Sites Inventory has this property been determined eligible? yes X no date 1986 federal X state county local depository for survey -

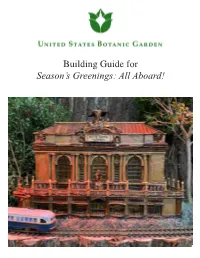

Train Station Models Building Guide 2018

Building Guide for Season’s Greenings: All Aboard! 1 Index of buildings and dioramas Biltmore Depot North Carolina Page 3 Metro-North Cannondale Station Connecticut Page 4 Central Railroad of New Jersey Terminal New Jersey Page 5 Chattanooga Train Shed Tennessee Page 6 Cincinnati Union Terminal Ohio Page 7 Citrus Groves Florida Page 8 Dino Depot -- Page 9 East Glacier Park Station Montana Page 10 Ellicott City Station Maryland Page 11 Gettysburg Lincoln Railroad Station Pennsylvania Page 12 Grain Elevator Minnesota Page 13 Grain Fields Kansas Page 14 Grand Canyon Depot Arizona Page 15 Grand Central Terminal New York Page 16 Kirkwood Missouri Pacific Depot Missouri Page 17 Lahaina Station Hawaii Page 18 Los Angeles Union Station California Page 19 Michigan Central Station Michigan Page 20 North Bennington Depot Vermont Page 21 North Pole Village -- Page 22 Peanut Farms Alabama Page 23 Pennsylvania Station (interior) New York Page 24 Pikes Peak Cog Railway Colorado Page 25 Point of Rocks Station Maryland Page 26 Salt Lake City Union Pacific Depot Utah Page 27 Santa Fe Depot California Page 28 Santa Fe Depot Oklahoma Page 29 Union Station Washington Page 30 Union Station D.C. Page 31 Viaduct Hotel Maryland Page 32 Vicksburg Railroad Barge Mississippi Page 33 2 Biltmore Depot Asheville, North Carolina built 1896 Building Materials Roof: pine bark Facade: bark Door: birch bark, willow, saltcedar Windows: willow, saltcedar Corbels: hollowed log Porch tread: cedar Trim: ash bark, willow, eucalyptus, woody pear fruit, bamboo, reed, hickory nut Lettering: grapevine Chimneys: jequitiba fruit, Kielmeyera fruit, Schima fruit, acorn cap credit: Village Wayside Bar & Grille Wayside Village credit: Designed by Richard Morris Hunt, one of the premier architects in American history, the Biltmore Depot was commissioned by George Washington Vanderbilt III. -

Phase II and Phase III Archeological Database and Inventory Site Number: 18HO35 Site Name: B&O Round Table at Ellicott C

Phase II and Phase III Archeological Database and Inventory Site Number: 18HO35 Site Name: B&O Round Table at Ellicott C. Prehistoric Other name(s) Historic Brief 19th century railroad station roundtable Unknown Description: Site Location and Environmental Data: Maryland Archeological Research Unit No. 14 SCS soil & sediment code Mo Latitude 39.2743 Longitude -76.7891 Physiographic province Eastern Piedmont Terrestrial site Underwater site Elevation 48 m Site slope 0% Ethnobotany profile available Maritime site Nearest Surface Water Site setting Topography Ownership Name (if any) Patapsco River -Site Setting restricted Floodplain High terrace Private Saltwater Freshwater -Lat/Long accurate to within 1 sq. mile, user may Hilltop/bluff Rockshelter/ Federal Ocean Stream/river need to make slight adjustments in mapping to cave Interior flat State of MD account for sites near state/county lines or streams Estuary/tidal river Swamp Hillslope Upland flat Regional/ Unknown county/city Tidewater/marsh Lake or pond Ridgetop Other Unknown Spring Terrace Low terrace Minimum distance to water is 16 m Temporal & Ethnic Contextual Data: Contact period site ca. 1820 - 1860 P Ethnic Associations (historic only) Paleoindian site Woodland site ca. 1630 - 1675 ca. 1860 - 1900 P Native American Asian American Archaic site MD Adena ca. 1675 - 1720 ca. 1900 - 1930 African American Unknown Early archaic Early woodland ca. 1720 - 1780 Post 1930 Anglo-American Y Other MIddle archaic Mid. woodland ca. 1780 - 1820 Hispanic Late archaic Late woodland Unknown historic context Unknown prehistoric context Unknown context Y=Confirmed, P=Possible Site Function Contextual Data: Historic Furnace/forge Military Post-in-ground Urban/Rural? Urban Other Battlefield Frame-built Domestic Prehistoric Transportation Fortification Masonry Homestead Multi-component Misc. -

Union Dam and Mill Race; Union Manufacturing Company Sites)

HO-534 Union Dam (Union Dam and Mill Race; Union Manufacturing Company Sites) Architectural Survey File This is the architectural survey file for this MIHP record. The survey file is organized reverse- chronological (that is, with the latest material on top). It contains all MIHP inventory forms, National Register nomination forms, determinations of eligibility (DOE) forms, and accompanying documentation such as photographs and maps. Users should be aware that additional undigitized material about this property may be found in on-site architectural reports, copies of HABS/HAER or other documentation, drawings, and the “vertical files” at the MHT Library in Crownsville. The vertical files may include newspaper clippings, field notes, draft versions of forms and architectural reports, photographs, maps, and drawings. Researchers who need a thorough understanding of this property should plan to visit the MHT Library as part of their research project; look at the MHT web site (mht.maryland.gov) for details about how to make an appointment. All material is property of the Maryland Historical Trust. Last Updated: 03-25-2016 Union Dam and Mill Race (H0-534) Patapsco Valley State Park R. Christopher Goodwin & Associates, Inc. December 2010 Page I of7 Addendum 7.1 Description Introduction This addendum to the Maryland Inventory of Historic Properties Form for the Union Dam (H0-534) was prepared to document the results of the archeological monitoring undertaken at the site between June 1 and July 3, 2010 to address the unexpected discovery of the partial remains of three timber structures within the channel of the Patapsco River. These structural remains were encountered during the removal of the 1912 reinforced concrete Union Dam. -

2016 Master Plan Committee Document

City of Laurel Master Plan Goals, Objectives, and Policies ADOPTED BY THE MAYOR AND CITY COUNCIL OF LAUREL ____________ ____, 2016 – ORDINANCE NO. ____ February 2016 Draft 8103 SANDY SPRING ROAD LAUREL, MARYLAND CITY OF LAUREL Mayor: Craig A. Moe City Council: H. Edward Ricks, President Michael R. Leszcz, President Pro Tem Valerie M. A. Nicholas, First Ward Donna L. Crary, Second Ward Frederick Smalls, Second Ward In Conjunction With the Planning Commission Mitzi R Betman, Chairwoman John R. Kish, Vice Chairman Frederick Smalls, Ex-Officio Member Bill Wellford Donald E. Williford G. Rick Wilson And the Master Plan Review Committee Richard Armstrong Pam Brown Toni Drake Samuel Epps Roy P. Gilmore Douglas Hayes Steve Meyerer Luther Roberts G. Rick Wilson __________ ___, 2016 1 ABSTRACT Title City of Laurel Master Plan Author: Department of Community Planning and Business Services Maps: Department of Information Technology Subject: Master Plan for the City of Laurel. Elements include land use, municipal growth, community facilities, water resources, public safety, transportation, recreation, sensitive areas, and implementation. Date: __________ ____, 2016 Abstract: This document sets forth recommendations for the future development and growth of the City. Specific recommendations are made for the many elements integral to the functioning of the City including land use proposals, transportation concerns, capital improvements and the physical and living environments. The focus of the document is to provide a long- range plan for the retention of the traditional characteristics of Laurel with the integration of future land use development. 2 ORDINANCE NO. ____ AN ORDINANCE TO APPROVE AND ADOPT A MASTER PLAN FOR THE CITY OF LAUREL Sponsored by the President at the request of the Administration.