Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Castle Hill Ymca Winter/Spring 2020 We Are Y

NEW! CUSTOMIZE YOUR MEMBERSHIP! See Inside for Details WE ARE Y PROGRAM & CLASS GUIDE CASTLE HILL YMCA WINTER/SPRING 2020 2 Castle Hill Avenue Bronx, NY 10473 212-912-2490 ymcanyc.org/castlehill WHY THE Y NO HIDDEN FEES • NO ANNUAL FEES • NO PROCESSING FEES • NO CONTRACTS ADULT/SENIOR FAMILY AMENITIES, PROGRAMS, AND CLASSES MEMBERSHIP MEMBERSHIP Member discounts and priority registration l l State-of-the-art fitness center l l Over 60 FREE weekly group exercise classes l l FREE YMCA Weight Loss Program l l Y Fit Start (FREE 12-week fitness program) l l One Indoor & Two Outdoor Swimming Pools l l Sauna l l Basketball court l l FREE Parking Lot l l FREE WiFi l l Customizable Family & Household Memberships l FREE family classes l FREE teen orientation to the fitness center l FREE teen programs l Convenient family locker room l FREE Child Watch l 212-912-2490 ymcanyc.org/castlehill @bronxymca facebook.com/bronxymca @bronxymca TABLE OF CONTENTS ADULTS ................................ 4 KIDS & FAMILY (AGES 0-4) .... 8 YOUTH (AGES 5-12) ............ 10 TEENS (AGES 12-17) ........... 14 SWIM .................................. 16 SUMMER CAMP .................. 22 EVENTS/RENTALS .............. 26 JOIN THE Y .......................... 30 Dear Castle Hill YMCA Member, LOCATIONS ........................ 35 Welcome to another exciting year at the YMCA of Greater New York! We look forward to serving you and your family with a variety of wonderful programs in 2020! HOURS OF OPERATION OPEN 364 DAYS A YEAR The New Year is my favorite time of year. It’s an opportunity to reflect, refresh, and reset. If you want to try something new in Monday - Friday: 5:30 AM - 10:00 PM 2020, we have a world of options. -

General Info.Indd

General Information • Landmarks Beyond the obvious crowd-pleasers, New York City landmarks Guggenheim (Map 17) is one of New York’s most unique are super-subjective. One person’s favorite cobblestoned and distinctive buildings (apparently there’s some art alley is some developer’s idea of prime real estate. Bits of old inside, too). The Cathedral of St. John the Divine (Map New York disappear to differing amounts of fanfare and 18) has a very medieval vibe and is the world’s largest make room for whatever it is we’ll be romanticizing in the unfinished cathedral—a much cooler destination than the future. Ain’t that the circle of life? The landmarks discussed eternally crowded St. Patrick’s Cathedral (Map 12). are highly idiosyncratic choices, and this list is by no means complete or even logical, but we’ve included an array of places, from world famous to little known, all worth visiting. Great Public Buildings Once upon a time, the city felt that public buildings should inspire civic pride through great architecture. Coolest Skyscrapers Head downtown to view City Hall (Map 3) (1812), Most visitors to New York go to the top of the Empire State Tweed Courthouse (Map 3) (1881), Jefferson Market Building (Map 9), but it’s far more familiar to New Yorkers Courthouse (Map 5) (1877—now a library), the Municipal from afar—as a directional guide, or as a tip-off to obscure Building (Map 3) (1914), and a host of other court- holidays (orange & white means it’s time to celebrate houses built in the early 20th century. -

Harlem Y Summer/Fall 2018

DISCOVER 180 West 135th Street YOUR Y New York, NY 10030 212.912.2100 ymcanyc.org/harlem HARLEM Y facebook.com/harlemy SUMMER/FALL 2018 180 West 135th Street New York, NY 10030 212.912.2100 ymcanyc.org/harlem GET INVOLVED JOIN US TO HELP NEW YORKERS SUCCEED GIVE YOUR FELLOW NEW YORKERS A CHANCE TO THRIVE Visit www.ymcanyc.org/give to support OUR VISION our nonprofit mission. Active, engaged New Yorkers VOLUNTEER TO STRENGTHEN YOUR COMMUNITY building stronger communities. Email [email protected] to learn more. WATCH US GROW IN THE BRONX OUR MISSION Visit www.ymcanyc.org/bronx2020 to monitor progress on our new We’re here for all New Yorkers — Bronx branches. to empower youth, improve health, FOLLOW US and strengthen community. Check Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram for the latest updates on everything happening at New York City’s YMCA. HARLEM INFORMATION STAFF LISTING HOURS OF OPERATION 2018 SUMMER/FALL SESSION & REGISTRATION DATES Steve Lawrence – Executive Director ADULTS 212-912-2111, [email protected] Monday - Friday: 5:30 AM - 11:00 PM SUMMER REGISTRATION DATES Saturday 6:00 AM - 8:00 PM Member: June 16, 2017 Latoya Jackson - Associate Executive Director Sunday: 8:00 AM - 8:00 PM Community: June 23, 2017 212-912-2162, [email protected] Jamal Williams - Fund Development & TEENS SESSION DATES: Communications Director (School holidays & summer hours vary; refer to July 2, 2018 - August 26, 2018 212-912-2164, [email protected] website for a current schedule.) Monday - Friday: 2:30 - 8:00 PM FALL I REGISTRATION DATES Saturday -

'Silent Arrival': the Second Wave of the Great Migration and Its Affects on Black New York, 1940-1950

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2013 The 'Silent Arrival': The Second Wave of the Great Migration and Its Affects on Black New York, 1940-1950 Carla J. Dubose-Simons The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2231 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] THE ‘SILENT ARRIVAL’: THE SECOND WAVE OF THE GREAT MIGRATION AND ITS AFFECTS ON BLACK NEW YORK, 1940-1950 by CARLA J. DUBOSE-SIMONS A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York. 2013 ii ©2013 Carla J. DuBose-Simons All Rights Reserved iii This manuscript has been read and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in History in satisfaction of the Dissertation requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ______________________ ___________________________________________ Date Judith Stein, Chair of Examining Committee ______________________ ___________________________________________ Date Helena Rosenblatt, Executive Officer Joshua Freeman _____________________________________________ Thomas Kessner ______________________________________________ Clarence Taylor ______________________________________________ George White ______________________________________________ The City University of New York iv ABSTRACT THE ‘SILENT ARRIVAL’: THE SECOND WAVE OF THE GREAT MIGRATION AND ITS AFFECTS ON BLACK NEW YORK, 1940-1950 By Carla J. DuBose-Simons Advisor: Judith Stein This dissertation explores black New York in the 1940s with an emphasis on the demographic, economic, and social effects the World War II migration of blacks to the city. -

To View Proposal

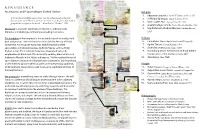

R E N A I S S A N C E Architecture and Placemaking in Central Harlem Religion 1. Abyssinian Baptist: Charles W. Bolton & Son, 1923 It is true the formidable centers of our race life, educational, industrial, 2. St Philip's Episcopal: Tandy & Foster, 1911 financial, are not in Harlem, yet here, nevertheless are the forces that make a 3. Mother AME Zion: George Foster Jr, 1925 group known and felt in the world. —Alain Locke, “Harlem” 1925 4. Greater Refuge Temple: Costas Machlouzarides, 1968 We intend to study the landmarks in Harlem to understand the 5. Majid Malcolm Shabazz Mosque: Sabbath Brown, triumphs and challenges of Black placemaking in America. 1965 The backdrop to this proposal is the national story of inequality, both Culture past and present. Harlem’s transformation into the Mecca of Black 6. Paris Blues: Owned by the late Samuel Hargress Jr. culture that we recognize today was enabled by failed white 7. Apollo Theater: George Keister, 1914 speculation and shrewd business by Black figures such as Philip 8. Studio Museum: David Adjaye, 2021 Payton Junior. The Harlem Renaissance blossomed out of the 9. Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture: neighborhood’s Black and African identity, enabling Black artists and Charles McKim, 1905; Marble Fairbanks, 2017 thinkers to flourish in the 1920s and beyond. Yet, the cyclical forces of 10. Showman’s Jazz Club speculation, rezoning and rising land values undermine this flourishing and threaten to uproot Harlem’s poorer and mostly Black population, People while landmark designations seek to preserve significant portions of 11. -

Harlem YMCA Winter | Spring 2013

LEARN GROW THRIVE harleM YMCA Winter | SPring 2013 HARLEM YMCA 180 West 135th Street New York, NY 10030 P 212.912.2100 ymcanyc.org/harlem WHY WE’re Here FOR Nurturing the potential of every child and teen YOUTH We believe that all kids deserve the opportunity to discover who they are and what DEVELOPMENT they can achieve. That’s why, through the YMCA, millions of youth today are cultivating the values, skills and relationships that lead to positive behaviors, better health and educational achievement. FOR Improving our community’s health and well-being HEALTHY In neighborhoods across the five boroughs, the YMCA is a leading voice on health LIVING and well-being. The Y brings families closer together, encourages good health and fosters connections through fitness, sports, fun and shared interests. As a result, nearly 400,000 youth, adults and families are receiving the support, guidance and resources needed to achieve greater health and well-being for their spirit, mind and body. FOR Giving back and providing support to our neighbors SOCIAL The YMCA has been listening and responding to New York City’s most critical social RESPONSIBILITY needs for 160 years. Whether developing skills or emotional well-being through education and training, welcoming and connecting diverse demographic populations through global services, or preventing chronic disease and building healthier communities through collaborations with policymakers, the Y fosters the care and respect all people need and deserve. We’re Here for Good. It’s been the signature phrase of New York City’s YMCA since early 2008, and it describes the Y’s commitment to building the foundations of—and strengthening—our communities, through nurturing the potential of every child and teen, improving community health and well-being and providing opportunities to give back and support neighbors. -

MXB Virtual Tour

Projects & Proposals > Manhattan > Virtual Tour of Malcolm X Boulevard Archived Content This page describes Malcolm X Boulevard as it appeared in 2001. The tour was developed as part of the Malcolm X Boulevard Streetscape Enhancement Project. Welcome! Welcome to Malcolm X Boulevard in the heart of Harlem! This online virtual tour highlights the landmarks of Harlem and is available in printable text form. Introduction: This tour was developed by the Department of City Planning as part of its Malcolm X Boulevard Streetscape Enhancement Project. The project, which extends from West 110th to West 147th Street, seeks to complement the ongoing capital improvements for Malcolm X Boulevard and take advantage of the growing tourist interest in Harlem. The project proposes a program of streetscape and pedestrian space improvements, including new pedestrian lighting, new sidewalk and median landscaping and the provision of pedestrian amenities, such as seating and pergolas. The Department has been working with Cityscape Institute, the Upper Manhattan Empowerment Zone, the New York City Department of Transportation, and the Department of Design and Construction, and has received implementation funds totaling $1.2 million through the federal TEA21 Enhancement Funding program for the proposed pedestrian lighting improvements. As one element of the project, the Department developed this guided tour of the boulevard and neighboring blocks. The tour provides an overview of local area history, and highlights architecturally significant and landmarked buildings, noteworthy cultural and ecclesiastical institutions and other points of interest. A listing of former famous jazz clubs, such as the Cotton Club and Savoy Ballroom, is also provided. Envisioned as an information resource for residents and visitors, the tour is also available in printable text format for use as a hand-held guide for a self-guided walking tour along the boulevard. -

Sfy 2004-2005 Legislative Initiative Form

SFY 2004-2005 LEGISLATIVE INITIATIVE FORM Legal Name, Address, and Telephone Number: CREATIVE ARTS TEAM, INC. 101 WEST 31ST STREET, 6TH FLOOR NEW YORK, NY 10001 (212) 652-2850 Project Title: SOCIAL-EMOTIONAL AWARENESS Funded Amount: $5,000 Purpose of Project: FUNDS WILL BE USED FOR AN ANTI-BULLYING AND ANTI-VIOLENCE PROGRAM AT IS 230, ENABLING THE STUDENTS TO LEARN ABOUT SOCIAL AND EMOTIONAL AWARENESS WHILE ALSO ADOPTING ALTERNATIVES TO VERBAL ABUSE AND HARASSMENT. Project Director: GWENDOLEN HARDWICK Requested By: DENDEKKER Name of Administering State Agency: CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK SFY 2004-2005 LEGISLATIVE INITIATIVE FORM Legal Name, Address, and Telephone Number: JOHN D. CALANDRA ITALIAN AMERICAN INSTITUTE 25 WEST 43RD STREET NEW YORK, NY 10036 (212) 642-2094 Project Title: ORAL HISTORY ARCHIVAL PROJECT Administering Organization: CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK Funded Amount: $5,000 Purpose of Project: FUNDS WILL BE USED FOR THE ORAL HISTORY OF ITALIAN-AMERICAN ELECTED OFFICIALS, WHICH WILL BE CREATED, RECORDED, ARCHIVED, AND MADE AVAILABLE TO THE PUBLIC THROUGH WEB STREAMING AND DVD. Project Director: ANTHONY JULIAN TAMBURRI Requested By: BENEDETTO Name of Administering State Agency: CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK SFY 2004-2005 LEGISLATIVE INITIATIVE FORM Legal Name, Address, and Telephone Number: RESEARCH FOUNDATION OF THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK 695 PARK AVENUE, ROOM W1611 NEW YORK, NY 10065 (212) 772-5599 Project Title: PUBLIC SERVICE SCHOLAR PROGRAM Funded Amount: $5,000 Purpose of Project: FUNDS WILL BE USED TO SUPPORT THE PUBLIC SERVICE SCHOLAR PROGRAM, WHICH TRAINS STUDENTS FOR LEADERSHIP POSITIONS IN PUBLIC SERVICE. Project Director: ELAINE M. WALSH HUNTER COLLEGE DEPT. -

A Historical Guide to Langston Hughes

A Historical Guide to Langston Hughes STEVEN C. TRACY, Editor OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS Langston Hughes The Historical Guides to American Authors is an interdisciplinary, historically sensitive series that combines close attention to the United States’ most widely read and studied authors with a strong sense of time, place, and history. Placing each writer in the context of the vi- brant relationship between literature and society, volumes in this series contain historical essays written on subjects of contemporary social, political, and cultural relevance. Each volume also includes a capsule biography and illustrated chronology detailing important cultural events as they coincided with the author’s life and works, while pho- tographs and illustrations dating from the period capture the flavor of the author’s time and social milieu. Equally accessible to students of literature and of life, the volumes offer a complete and rounded picture of each author in his or her America. A Historical Guide to Ernest Hemingway Edited by Linda Wagner-Martin A Historical Guide to Walt Whitman Edited by David S. Reynolds A Historical Guide to Ralph Waldo Emerson Edited by Joel Myerson A Historical Guide to Nathaniel Hawthorne Edited by Larry Reynolds A Historical Guide to Edgar Allan Poe Edited by J. Gerald Kennedy A Historical Guide to Henry David Thoreau Edited by William E. Cain A Historical Guide to Mark Twain Edited by Shelley Fisher Fishkin A Historical Guide to Edith Wharton Edited by Carol J. Singley A Historical Guide to Langston Hughes Edited by Steven C. Tracy A Historical Guide to Langston Hughes f . 1 3 Oxford New York Auckland Bangkok Buenos Aires Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kolkata Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi São Paulo Shanghai Taipei Tokyo Toronto Copyright © by Oxford University Press, Inc. -

16324 01 Trotter New York City VW.Indd

NEW YORK van reizigers voor reizigers TR TTER NEW YORK 4 De wereld houdt niet op met draaien. Een wereldreiziger is de eerste om dat te beamen. Hoewel men geen inspanningen gespaard heeft om al de gegevens in deze gids uitgebreid te testen en te actualiseren, is het niet uitgesloten dat je ter plaatse vaststelt dat bepaalde gegevens in deze gids toch al opnieuw gewijzigd zijn. Veel adressen en suggesties in de Trotters zijn bovendien wat ‘fragiel’, juist omdat ze zo sympathiek en verrassend zijn. We zouden het daarom bijzonder op prijs stellen als je ons op de hoogte brengt van eventuele wijzigingen, zodat we de eerstvolgende herdruk op een correcte manier kunnen aanpassen. Dank bij voorbaat. Ons adres: TROTTER Uitgeverij Lannoo Uitgeverij Terra Lannoo Kasteelstraat 97 Postbus 97 B-8700 Tielt NL-3990 DB Houten E-MAIL: [email protected] WWW.TROTTERCLUB.COM De prijscategorieën die in de Trottergidsen worden gebruikt, zijn steeds afgestemd op het land. Als je in een goedkoop hotelletje ongeveer € 25 betaalt, behoort een hotel waar je € 75 neertelt uiteraard tot de dure prijsklasse. De uitgever kan niet aansprakelijk worden gesteld voor eventuele fouten of de gevolgen ervan. VERTALING Petra van Caneghem; 2015 Imago Mediabuilders REISINFORMATIE VLAANDEREN EN NEDERLAND Wegwijzer, Brugge OMSLAGONTWERP Studio Jan de Boer / Helga Bontinck ONTWERP BINNENWERK Imago Mediabuilders OMSLAGFOTO Marcio Jose Bastos Silva / Shutterstock OORSPRONKELIJKE TITEL Le Routard – New York + Brooklyn OORSPRONKELIJKE UITGEVER Hachette, Paris DIRECTEUR VAN DE REEKS -

South Shore YMCA Fall I & II 2019 PROGRAM & CLASS GUIDE

DISCOVER YOUR Y South Shore YMCA Fall I & II 2019 PROGRAM & CLASS GUIDE 3939 Richmond Avenue Staten Island, NY 10312 718-227-3200 ymcanyc.org/southshore CONTACT TABLE OF US CONTENTS PHONE: 718-227-3200 WHY THE Y ............................................................... 3 WEB: ymcanyc.org/southshore ADULTS .................................................................... 4 @SISouthShoreY KIDS & FAMILY (AGES 0-4) ......................................11 Facebook.com/sisouthshorey YOUTH (AGES 5-12) ................................................ 14 @sisouthshorey TEENS (AGES 12-17) ...............................................22 SWIM ...................................................................... 24 SOUTH SHORE Y BRANCH INFORMATION ............. 43 JOIN THE Y ..............................................................44 LOCATIONS ............................................................ 47 HOURS OF OPERATION OPEN 364 DAYS A YEAR Monday - Thursday: 5:00 AM - 11:00 PM Friday: 5:00 AM - 10:00 PM Saturday - Sunday: 6:00 AM - 9:30 PM 2019 SESSION & REGISTRATION DATES FALL I REGISTRATION DATES Member: August 17, 2019 Community: August 24, 2019 FALL I SESSION DATES: September 3 - October 27, 2019 FALL II REGISTRATION DATES Member: October 12, 2019 Community: October 19, 2019 FALL II SESSION DATES: October 28 - December 22, 2019 SESSION BREAK: December 23- January 1, 2020 WHY THE Y NO HIDDEN FEES NO ANNUAL FEES Where there’s a Y, there’s a way — to achieving your goals, supporting your NO PROCESSING FEES family, and strengthening -

HARLEM New Americans Initiative

NEWSLETTER Fall | 2019 HARLEM New Americans Initiative HARLEM WELCOMING WEEK 2019 On September 19th, 2019, the Harlem New Americans Initiative hosted a celebration of food and culture for 2019’s Welcoming Week. About 50 community members came by to enjoy a mix of Carribbean and Italian food! Also in attendance were several community partner organizations who provided valuable resources and information for attendees. These included Manhattan Legal Services, African Services Committee, Hot Bread Kitchen, Harlem Hospital, World Education Services, and the Greater Harlem Healthy Start Program. We also heard testimonies from current students Abla Awoudi, Victor Garcia Olivares, Ali Abdullah, Kadiatou Bah, and Maimouna Cisse— all of whom shared their stories of how the NAI and the YMCA have helped them to pursue and achieve their goals. Thanks to all who helped organize the event! Harlem is proud to welcome people from all over the world! pg 2 pg 3 pg 4 Citizenship Drive / CUNY Raffle Winners/ Coming Soon New Americans Welcome Center Goals Applied Theatre Project and Vision “When you rise in the morning, give thanks for the light, for your life, for your strength. Give thanks for your food and the joy of living. If you see no reason for giving thanks, the fault lies in yourself.” - Tecumseh CUNY Citizenship NOW! - Citizenship Drive in Harlem On December 18th, the Harlem NAI will be hosting a mini citizenship drive with the partnership of CUNY Citizenship Now! CUNY Citizenship Now will be providing pro bono lawyers and volunteers to help with the flow of the event. The purpose of the drive is to help people who think they are ready to apply for the naturalization test.