The Term Rape Culture: Empowering Or Redundant?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Exploratory Analysis of Sexual Violence and Rape Myth Acceptance

An Exploratory Analysis of Sexual Violence and Rape Myth Acceptance at a Small Liberal Arts University By Karla Wiscombe Submitted to the graduate degree program in Educational Leadership and Policy Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education. ________________________________ Chairperson Lisa Wolf-Wendel ________________________________ Susan Twombly ________________________________ Dongbin Kim ________________________________ Marc Mahlios ________________________________ Jennifer Ng Date Defended: June 4, 2012 The Dissertation Committee for Karla Wiscombe certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: An Exploratory Analysis of Sexual Violence and Rape Myth Acceptance at a Small Liberal Arts University ________________________________ Chairperson Lisa Wolf-Wendel Date approved: June 4, 2012 ii ABSTRACT Male perpetrated sexual violence is a highly prevalent, but underreported, crime on college campuses. Experts state that in order to effectively deal with the problem of sexual violence, it is important to determine the severity and nature of the problem. The purpose of this study was to provide data based evidence to define the actual problem of sexual violence on a specific college campus in order to raise awareness and provide baseline data for further examination of the issue of sexual violence. Risk factors for sexual violence were examined as well as demographic information for male and female students to determine the prevalence of sexual violence and the relationship of these known risk factors with incidents of sexual violence. Alcohol, Greek membership, athletic participation, and rape myth acceptance were analyzed to determine which factors contributed to the problem of sexual violence within this particular setting. -

Feminicide in Latin America.Pdf

Feminicide in Latin America Authors: Paula Norato, Gabriela Ramos-King and Alejandro Rodriguez Course: Power and Health in Latin America and the Caribbean, 2019 Abstract Violence against women has existed for centuries, specifically in Latin America as nation-states use this issue to oppress communities. Torture is used to strip women of their female identities in order to solicit information, obstetric violence is used to make women passive, and groups of women who speak and protest against feminicide are kidnapped, murdered, and raped. Governments disregard the existence of feminicide and do not create policies to act against it or programs to help those affected. Feminicide is carried out through state violence, suppression and restriction of reproductive and sexual rights, as well as a lack of policy and programs addressing socio-cultural dynamics around feminicide. This paper goes into depth at how each of these factors contribute to feminicide, what some countries are doing to fight against, which countries let it continue, and the groups of women both affected and acting against feminicide. Key Words: Feminicide, Systematic Violence, Reproductive rights, State Violence, Feminicide Policy Violence against women has existed for a very long time and has developed over centuries to be used as a tool to oppress communities. In today’s day and age, organizations like the World Health Organization (WHO) are joining together with Latin American governments and feminist researchers to better define violence against women in order to take action against it. The two most common terms used in this field are femicide and feminicide, however since research on this topic only began 30 years ago there is still room for improvement in terms of definitions. -

Femicide and the Feminist Perspective

HSX15410.1177/108876791142 4245414541Taylor and JasinskiHomicide Studies Homicide Studies 15(4) 341 –362 Femicide and the © 2011 SAGE Publications Reprints and permission: http://www. Feminist Perspective sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/1088767911424541 http://hs.sagepub.com Rae Taylor1 and Jana L. Jasinski2 Abstract The gender disparity in intimate killings underscores the need for close attention to the phenomenon of intimate partner–perpetrated femicides and theories useful in understanding this pervasive and enduring problem. The most overarching paradigm used is that of the feminist perspective. The purpose of this article is to review the tenets of feminist theory as the most viable and efficacious framework for understanding and explaining intimate partner–perpetrated femicide, to highlight empirical evidence supporting the strength and value of this perspective, to address the contentions of those in opposition to this perspective, and to provide research and policy implications targeted at greater understanding, and, ultimately, lower rates of femicide. Keywords femicide, feminist theory, intimate partner violence, intimate partner homicide, violence against women In the United States, slightly more than 16,000 individuals are victims of homicide each year (Fox & Zawitz, 2007), and men comprise the majority of victims and offend- ers of these homicides. For a number of years now, researchers have examined patterns of homicide victimization and offending to try to determine theoretical and empirical explanations for observed trends. Research considering demographic characteristics of homicide victims including gender, for example, is extensive (e.g., Gauthier & Bankston, 2004; Gruenewald & Pridemore, 2009). This research has considered not only gender differences in homicide prevalence over time but also gender differences in the victim–offender relationship (e.g., Swatt & He, 2006). -

Ethnic Minority Endorsement of Rape Myths Bianca Oney Nova Southeastern University, [email protected]

Nova Southeastern University NSUWorks College of Psychology Theses and Dissertations College of Psychology 1-1-2014 Ethnic Minority Endorsement of Rape Myths Bianca Oney Nova Southeastern University, [email protected] This document is a product of extensive research conducted at the Nova Southeastern University College of Psychology. For more information on research and degree programs at the NSU College of Psychology, please click here. Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/cps_stuetd Part of the Psychology Commons Share Feedback About This Item NSUWorks Citation Oney, B. (2014). Ethnic Minority Endorsement of Rape Myths. Available at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/cps_stuetd/94 This Dissertation is brought to you by the College of Psychology at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in College of Psychology Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running head: ETHNIC MINORITY ENDORSMENT OF RAPE MYTHS Ethnic Minority Endorsement of Rape Myths by Bianca Oney A Dissertation Presented to the School of Psychology of Nova Southeastern University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy NOVA SOUTHEASTERN UNIVERSITY 2014 Ethnic Minority Endorsement of Rape Myths 1 DISSERTATION APPROVAL SHEET This dissertation was submitted by Bianca Oney under the direction of the Chairperson of the dissertation committed listed below. It was submitted to the School of Psychology and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Clinical Psychology at Nova Southeastern University. Approved: __________________ ____________________________________ Date of Defense Lenore Walker, Ed.D., ABPP Chairperson ____________________________________ Alexandru Cuc, Ph.D. -

Femicide and Impunity in Bolivia “No Justice for Me” Femicide and Impunity in Bolivia

“No Justice for Me” Femicide and Impunity in Bolivia “No Justice for Me” Femicide and Impunity in Bolivia Acknowledgements Tis report was researched and written by Fabiola Alvelais, JD ‘20, Isabel Pitaro, JD ’20, Julia Wenck, ‘20, and Clinical Instructor Tomas Becker, JD ‘09, of Harvard Law School’s International Human Rights Clinic (IHRC) as well as Gemma Canham, BA ‘20, of Queens University Belfast. Te Clinic wishes to thank the many individuals who were willing to speak with us and share their stories to make this report possible. Contents 1 I. Executive Summary 1 2 3 4 5 6 2 7 Minimum Guide- Femicide 3 II. Methodology 4 III. -

Forms of Femicide

29 Forms of Femicide Facilitate. Educate. Collaborate. The opinions expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the AUTHOR views of the Government of Ontario or the Nicole Etherington, Research Associate, Learning Network, Centre for Research & Education on Violence Centre for Research and Education on Violence Against Women Against Women & Children. While all and Children, Faculty of Education, Western University. reasonable care has been taken in the preparation of this publication, no liability is assumed for any errors or omissions. SUGGESTED CITATION Etherington, N., Baker, L. (June 2015). Forms of Femicide. Learning Network Brief (29). London, Ontario: Learning The Learning Network is an initiative of the Network, Centre for Research and Education on Violence Centre for Research & Education on Violence Against Women and Children. against Women & Children, based at the http://www.vawlearningnetwork.ca Faculty of Education, Western University, London, Ontario, Canada. Download copies at: http://www.vawlearningnetwork.ca/ Copyright: 2015 Learning Network, Centre for Research and Education on Violence against Women and Children. www.vawlearningnetwork.ca Funded by: Page 2 of 5 Forms of Femicide Learning Network Brief 29 Forms of Femicide Femicide is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as ‘the intentional killing of women because they are women; however, a broader definition includes any killings of women and girls.’i Femicide is the most extreme form of violence against women on the continuum of violence and discrimination against women and girls. There are numerous manifestations of femicide recognized by the Academic Council on the United Nations System (ACUNS) Vienna Liaison Office. ii It is important to note that the following categories of femicide are not always discrete and may overlap in some instances of femicide. -

Knowing Her Name: the Framing of Sexual Assault Victims and Assailants in News Media

Knowing Her Name: The Framing of Sexual Assault Victims and Assailants in News Media Headlines A thesis submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Communication, College of Arts and Sciences by Tessa Webb B.A. University of Cincinnati, December 2017 Advisor: Nancy Jennings, PhD. Committee: Omotayo Banjo, PhD. and Ronald Jackson, III, PhD. Abstract: By examining how attribution of responsibility is constructed by public opinion, this research determines the discrepancy in the presence of the victim and their sexual assailant in news media headlines. This research is based in the theoretical framework of framing, which will be used to evaluate how electronic news media sources portray these stories and the ways in which they possibly alter truth through agenda setting and priming. Rape myths grow within our society through repetition, so the theoretical basis of the cumulative and cognitive-transactional model of media effects will be utilized in order to focus on the consonance and repetition of themes and messages that occur across media content. A content analysis will examine the ways in which electronic news media headlines are more likely to utilize language of support and use more description for the sexual assailant, as opposed to their victim. Content analyzed will include electronic news media headlines related to the Stanford sexual assault trial. ii iii Acknowledgments: I would first like to acknowledge the support of my advisor, Dr. Nancy Jennings. Your patience and support are the reason why I survived such a harsh topic of research. -

FEMICIDE and the MEDIA: Do Reporting Practices Normalize Gender-Based Violence?

Policy Brief No. 1 FEMICIDE AND THE MEDIA: Do reporting practices normalize gender-based violence? SUMMARY Feminist activism in the context of the novel coronavirus has cast renewed light on an extreme form of gender-based violence: femicide. Several countries in Latin America reported spikes in femicide in the early months of state-wide lockdowns, even in places where laws against femicide are in place. Research shows that lack of implementation and enforcement of laws, as well as data gaps and gender and other forms of discrimination all contribute to impunity. This policy brief presents evidence and makes recommendations to address another factor in the persistence of femicide: media reporting. It makes the case for a role for the news media in challenging, rather than reproducing, harmful stereotypes and attitudes. It also suggests a gender-sensitive and rights-based approach to femicide reporting that leverages and adapts existing frameworks to address femicide in specific country contexts. 01 Policy Brief No. 1 Femicide: a social and political phenomenon Femicidei refers to the gender-related killing of women The rise of femicide during which often culminates in socially and politically tolerated murder. It constitutes the most extreme end Covid-19 of a continuum of gender-based violence (GBV), violating women’s right to life and freedom from violence, torture, and gender-based discrimination. Data on GBV during the Covid-19 pandemic from Femicide is a global phenomenon that takes place in around the globe show an intensification of sexual both private and public spheres, though more than and physical violence, and especially domestic half of the 87,000 women intentionally killed in 2017 violence, leading to calls to address a “shadow xi were killed by intimate partners or other family pandemic.” Several countries in Latin America membersii. -

No. 27 November 15, 2018

No. 27 November 15, 2018 Femicide, the most extreme expression of violence against women At least 2,795 women were victims of femicide in 23 Latin American and Caribbean countries in 2017, according to data provided by national public agencies to ECLAC’s Gender Equality Observatory for Latin America and the Caribbean. In El Salvador this phenomenon is particularly acute, finding no other parallel in any country in the region, with a rate of 10.2 femicides per 100,000 women in 2017. This is followed by Honduras, which in 2016 registered 5.8 femicides per 100,000 women. In Guatemala, the Dominican Republic and Bolivia (Plur. State of) high rates were also observed for 2017, which are equal to or greater than 2 cases per 100,000 women. Venezuela, Panama and Peru are the only countries in the region with rates below 1.0. Figure 1 Latin America (16 countries): Femicides, last year with available information (Absolute numbers and rates per 100,000 women) Source: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), Gender Equality Observatory for Latin America and the Caribbean [online] http://oig.cepal.org/en, on the basis of official sources. * Chile and Colombia record information only on cases of intimate femicide, committed by intimate or former intimate partner. The data shows that femicides (homicides of women perpetrated for gender-based reasons) usually correspond to a majority of the total intentional homicides of women. In most countries of the region with available data, femicides are committed by someone with whom the victim had or had had an intimate relationship. -

Pregnancy, Femicide, and the Indispensability of Legalizing Abortion: a Comparison Between Argentina and Ireland

Emory International Law Review Volume 34 Issue 3 2020 Pregnancy, Femicide, and the Indispensability of Legalizing Abortion: A Comparison Between Argentina and Ireland Agustina M. Buedo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/eilr Recommended Citation Agustina M. Buedo, Pregnancy, Femicide, and the Indispensability of Legalizing Abortion: A Comparison Between Argentina and Ireland, 34 Emory Int'l L. Rev. 825 (2020). Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.emory.edu/eilr/vol34/iss3/3 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Emory Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Emory International Law Review by an authorized editor of Emory Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUEDOPROOFS_5.11.20 5/11/2020 1:12 PM PREGNANCY, FEMICIDE, AND THE INDISPENSABILITY OF LEGALIZING ABORTION: A COMPARISON BETWEEN ARGENTINA AND IRELAND INTRODUCTION Although Argentina has relatively high levels of education, strong civil- society groups, and a long history of feminist activism, the country remains stagnant on change regarding women’s rights, specifically, reproductive rights.1 Among the long-standing human rights problems in Argentina is the “endemic violence against women, restrictions on abortion, [and] difficulty accessing reproductive services.”2 Argentine law considers abortion a crime with the exception of two narrowly defined circumstances: (a) if the abortion is carried out with the purpose of averting risk to the mother’s life or health when that risk cannot be averted by any other measure; or (b) in the case of the rape of a mentally disabled woman.3 This kind of law perpetuates both the cultural and institutional restraints surrounding abortion that are “paradigmatic of how women’s bodies are socially regulated in Argentina.”4 Restricting abortion has severe implications—more violence against women. -

Evaluating Social Judgments of Acquaintance Rape Myths Michelle E

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 5-2017 Context Matters: Evaluating Social Judgments of Acquaintance Rape Myths Michelle E. Deming University of South Carolina Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Deming, M. E.(2017). Context Matters: Evaluating Social Judgments of Acquaintance Rape Myths. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/4068 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONTEXT MATTERS: EVALUATING SOCIAL JUDGMENTS OF ACQUAINTANCE RAPE MYTHS by Michelle E. Deming Bachelor of Arts University of North Carolina at Wilmington, 2007 Master of Arts University of North Carolina at Wilmington, 2009 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2017 Accepted by: Shelley A. Smith, Major Professor Douglas L. Anderton, Committee Member Suzanne C. Swan, Committee Member Jason L. Cummings, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Michelle E. Deming, 2017 All Rights Reserved. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you Shelley Smith for your guidance, encouragement, and patience throughout this journey. I also wish to thank Douglas Anderton for your contribution to the methodology and analyses. Thank you Suzanne Swan, Deborah Billings, and Jason Cummings for your assistance in putting all of these pieces together. Finally, to MD, LD, TD, BD, PD, LB, SS, GD, and BG…I couldn’t have completed this without you. -

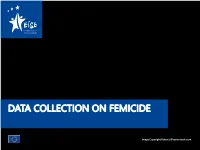

Data Collection on Femicide

DATA COLLECTION ON FEMICIDE Image Copyright:fizkes's/Shutterstock.com CHALLENGES FOR DATA COLLECTION • No international defintion of “femicide” • Terminology of femicide not adapted to statistical purposes • Lack of disaggregated approaches to data collection • Technical obstacles in data collection at national level LEGISLATIVE CONTEXT Victims’ Istanbul Rights Convention Directive Report of CEDAW GR UNODC 35 (49) (2019) & Road Map DEFINITIONS BY ACADEMIA The killing of females by males because they are females (Russell, D. 1976) The murder of women by men motivated by hatred, contempt, pleasure or a sense of ownership over women (Caputi and Russell 1990) The misogynistic killings of women by men (Radford & Russell, 1992) DEFINITIONS OF INTERNATIONAL ORGANISATIONS Vienna WHO MESECVI ICCS Declaration (UN) Femicide is the The The violent killing of women An unlawful death killing of women and intentional because because of gender, inflicted upon a girls because of their murder of whether it occurs within the person with the gender women family, domestic unit or any intent to cause because they other interpersonal death or serious are women relationship, within the injury community, by any individual or when committed or tolerated by the state or its agents, either by act or omission COMPONENTS Intentional Killing 24 Death related to unsafe abortion 14 FGM-related death 9 Killing of a partner or espouse 7 Gender-based act and/or killing of a woman 6 Death of women resultinf of IPV 5 COMPONENTS OF FEMICIDE OF COMPONENTS Dowry-related deaths Females foeticide Honour-based Killings 0 10 20 30 NUMBER OF MEMBER STATES COMPONENTS KEY COMPONENTS Gender Gender inequalities motivation EIGE’s DEFINITION AND INDICATOR The killing of a woman by an intimate partner and the death of a woman as a result of a practice that is harmful to women.