Father Francis Gilligan and the STRUGGLE for CIVIL RIGHTS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monthly Publication for the Catholic Diocese of Sioux Falls July 2020 God’S Promptings in the Silence of My Heart

Monthly publication for the Catholic Diocese of Sioux Falls July 2020 God’s promptings in the silence of my heart n each of my assignments as particular experience, passion and pastor and now as your bishop, I gifts in one or another of these areas have received a particular grace of formation. We are in a great posi- I(spiritual insight from God) to provide tion to help every parish take the next a clear vision or focus for everyone to best step they can in responding to the follow. The clear sense I got in prayer Great Commission.” for our diocese is that God desires for everyone in our diocese to focus Fr. Traynor points out that this is not on lifelong missionary discipleship a one size fi ts all approach. He says through God’s love. parishes and individual believers will be formed in their own unique way to Our feature article this month is writ- respond to the Great Commission. ten by Fr. Scott Traynor who is work- ing with the diocesan Discipleship and “Every parish and every person has a Evangelization Team so they all can unique history, a unique set of needs, support the missionary discipleship opportunities, relationships, resources eff orts of clergy, staff and parishioners and abilities,” Fr. Traynor says. “The in all our Catholic parishes, schools Discipleship and Evangelization and other Catholic institutions. Here Team treasures the relationships we are some insights from Fr. Traynor have with pastors and parish leaders and the team he is overseeing. around the diocese. We are eager to grow those relationships so we can The team has been engaged in fruit- more fruitfully serve parishes in their ful eff orts around the diocese over the eff orts to advance missionary disciple- past several years. -

Mass Schedule

SEPTEMBER, 27 2020 WELCOME! Our Parish Mission is to build on the warmth and spirit of community established by the Irish Catholic immigrants who founded the parish in 1857 with our own commitment of faith, centered on the gospel of Jesus Christ by: providing faith-filled worship focused on the celebration of Eucharist; being a welcoming community; recognizing our need to continue our formation as Christians; providing an environment of holiness in our homes; and striving to acknowledge our blessings through our generosity. MASS SCHEDULE MONDAY–FRIDAY: 8:00am SATURDAY: 5:00pm SUNDAY: 9:00am, 11:00 am 5:00pm ALL MASSES IN CHURCH 6820 ST. PATRICK’S LANE | EDINA, MN | (952) 941-3164 | WWW.STPATRICK-EDINA.ORG 2 Prayer & Worship Please plan to attend one of two planned Church Hall Meetings. Topics to be covered in the hour meeting: facility maintenance and yard work; CEND; Faith Formation for youth and adults; and future plans. There will be time for Q&A. Open and clear communication is vital in The meetings are scheduled for Thursday, every relationship and is essential in our October 1st and Tuesday October 6th at parish family life. Covid-19 has impacted 6:30 p.m. in the church with the usual this. Recently I met with two groups of pandemic precautions. parishioners who desired to hear what has been happening in the parish and where Respectfully, are moving into the future. These Fr. Kuss impromptu meetings provided reassurance to those present and answered questions that had been floating in the community. The two meetings enabled me to come to know the concerns of our community and provided welcome and needed input for me to provide the sound pastoral leadership. -

Fraternal Brotherhood

VIANNEYNEWS SAINT JOHN VIANNEY COLLEGE SEMINARY SAINT JOHN VIANNEY SPRING 2020 COLLEGE SEMINARY FRATERNAL BROTHERHOOD 1 Dear Friends, When we planned this issue of Vianney News earlier this year, COVID-19 was just beginning to fill the headlines. Today, it impacts every aspect of our lives. The precious gift of our Catholic faith has sustained us and directed us to Easter Sunday when together we proclaimed, “Alleluia, He is risen!” I pray that you and your loved ones remain healthy and are comforted by this promise of everlasting life. As concerns surrounding the Coronavirus spread in March, we made the difficult but prudent decision to bring home 14 SJV seminarians living in Rome for spring semester. I regret that they could not complete their semester abroad, but I trust that the heart of our Church will remain in them. (See pages 6 and 7 for updates from the fall Rome experience.) Shortly thereafter, more than 90 men in formation at SJV were required to move out of the seminary. Most returned to their home dioceses; some are living in cloister at a nearby retreat center with members of the SJV priest staff. All will continue their academic and spiritual formation in new settings off campus. I am very proud of our seminarians and the maturity they have displayed as their college seminary experience significantly changed. They trust in God’s plan for their lives, and they continue to discern under new circumstances. Throughout this issue, you will read about the importance of college seminary formation. Our feature story on fraternal brotherhood (pages 8-11) illustrates the genuine bond of brotherhood fostered at SJV. -

B~'J.I ~L:Etin

B~'J.I ~L:ETIN OCTOBER LETTER OF HIS HOLINESS, POPE PIUS XI Praising Bishops of United States for Results Achieved Through N. C. W. C. REPORT OF BISHOPS' ANNUAL MEETING Held at Washington, D. C., September 14-15 SUMMARIES OF 1927 REPORTS Of the Members of the N. C. W. C. Administrative Committee PROGRAM OF THE 7TH ANNUAL C()NVENTION OF N. C. C. w. Held at Washington, D. C., September 25-28 Special Features Holy Father Gives $100,000 to Relieve Mississippi Flood Victims-Report of the Los Angeles Meeting of the National Conference of Catholic Charities-Catholic School Program for American Education Week-Plans lor the 7th Annual Convention 'of the N. C. C. M.,- Detroit, Michigan, October 16·18 N. C. W. C. Administrative Committee Thanked at Bishops' Meeting 2 N.C.W.C. BULLETIN October, 1927 Members of N. C. W. C. Admin istrative Committee Thanked by Fellow Bishops at Annual Meeting OLLOWING A GLOWING TRIBUTE by His Eminence Cardinal Hayes, of New York, to the members of the Adminis N. C. oW. C. F trative Committee of Archbishops and Bishops of the National Catholic Welfare Conference and the results achieved through their BULLETIN unceasing labors in promoting the various works of the Conference, the entire body of Bishops expressed their concurrence in Cardinal Hayes' remarks in a standing vote of thanks and appreciation. Published Monthly by the NATIONAL CATHOLIC WELFARE THE incident took place at the completion of the 1927 meeting of the Cardi- CONFERENCE nals, Archbishops and Bishops of the United States which had devoted the greater part of two days to the consideration of the reports of the Episcopal PUBLICATION OFFICE Chairmen of the N. -

Results of Elections Attorneys General 1857

RESULTS OF ELECTIONS OF ATTORNEYS GENERAL 1857 - 2014 ------- ※------- COMPILED BY Douglas A. Hedin Editor, MLHP ------- ※------- (2016) 1 FOREWORD The Office of Attorney General of Minnesota is established by the constitution; its duties are set by the legislature; and its occupant is chosen by the voters. 1 The first question any historian of the office confronts is this: why is the attorney general elected and not appointed by the governor? Those searching for answers to this question will look in vain in the debates of the 1857 constitutional convention. That record is barren because there was a popular assumption that officers of the executive and legislative branches of the new state government would be elected. This expectation was so deeply and widely held that it was not even debated by the delegates. An oblique reference to this sentiment was uttered by Lafayette Emmett, a member of the Democratic wing of the convention, during a debate on whether the judges should be elected: I think that the great principle of an elective Judiciary will meet the hearty concurrence of the people of this State, and it will be entirely unsafe to go before any people in this enlightened age with a Constitution which denies them the right to elect all the officers by whom they are to be governed. 2 Contemporary editorialists were more direct and strident. When the convention convened in St. Paul in July 1857, the Minnesota Republican endorsed an elected judiciary and opposed placing appointment power in the chief executive: The less we have of executive patronage the better. -

Solemnity of the Most Holy Trinity | May 22, 2016

SOLEMNITY OF THE MOST HOLY TRINITY | MAY 22, 2016 CATHEDRAL OF SAINT PAUL NATIONAL SHRINE OF THE APOSTLE PAUL 239 Selby Avenue, Saint Paul, Minnesota 55102 651.228.1766 | www.cathedralsaintpaul.org Rev. John L. Ubel, Rector | Rev. Eugene Tiffany Deacons Phil Stewart, Russ Shupe, & Nao Kao Yang ARCHDIOCESE OF SAINT PAUL AND MINNEAPOLIS Most Reverend Bernard A. Hebda, Archbishop Most Reverend Andrew H. Cozzens, Auxiliary Bishop LITURGY GUIDE FOR THE SOLEMNITY OF THE MOST HOLY TRINITY PHOTOGRAPHY — The Cathedral welcomes all visitors to THE LITURGY OF THE WORD Mass today. We encourage those who wish to take photos of 866 this sacred space to do so freely before and after Mass. Once FIRST READING Proverbs 8:22-31 the opening announcement is made, please refrain from taking photos and videos until Mass has concluded. Thank you. RESPONSORIAL PSALM USCCB/New American Bible Psalm 8:4-5, 6-7, 8-9 Saint Noël Chabanel OPENING HYMN NICAEA 485 Holy, Holy, Holy! Lord God Almighty INTROIT (8:00 a.m. & 10:00 a.m.) Caritas Dei Gregorian Missal, Mode III Verses from Lectionary for Mass Cáritas Dei diffúsa est in córdibus nostris, allelúia: per inhabitántem Spíritum eius in nobis, allelúia, allelúia. Ps. Bénedic ánima mea Dómino: et ómnia quæ SECOND READING Romans 5:1-5 intra me sunt, nómini sancto eius. The love of God has been poured into our hearts, alleluia; by his Spirit which GOSPEL John 16:12-15 dwells in us, alleluia, alleluia. ℣. Bless the Lord, O my soul; and all that is Deacon: The Lord be with you. -

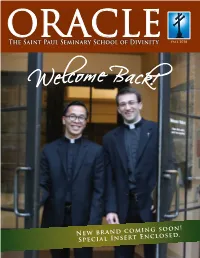

Welcome Back!

ORACLE fall 2018 The Saint Paul Seminary School of Divinity Welcome Back! New brand coming soon! Special Insert Enclosed. 445742_V1.indd 1 10/22/18 6:46 PM from the rector together we are joyful, catholic leaders Dear Friends, A new year of formation has begun at The Saint Paul Seminary School of Divinity. It is a privilege for me to serve as the Interim Rector for the fall semester. Building upon the 13-year legacy of Msgr. Aloysius Callaghan, I look forward to welcoming our newly appointed Rector Fr. Joseph Taphorn on January 1. God has blessed this institution with faithful leadership. I am grateful that I can play a small part during this time of transition. While I see God at work every day in our seminarians, lay students, priests, diaconate candidates, faculty and staff, I realize this has been a time of uncertainty for many of us in the Church. Revelations of sexual abuse of minors by ordained clergy have been very painful and have caused us to pause, to question and to pray. We have had and will continue to have, as a seminary community, thoughtful and practical discussion about the formation we offer and the processes we follow to make sure the seminary is a holy place forming holy priests. We are grateful that God is shining His light in the darkness, and we are responding in faith with the gifts He has given us. Simultaneously, there is good news to share. I hope you will be inspired by the stories you read in this issue. -

Going Global Minnesota Law Alumni Are Making a World of Difference

FALL 2019 THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA LAW SCHOOL MAGAZINE + U.S. SUPREME COURT Stein Lecture Features Justice Elena Kagan FACULTY MILESTONE Prof. Fred Morrison Celebrates 50 Years Teaching at Law School ALUMNI Q&A Bethany Owen ’95 President of ALLETE Inc. Going Global Minnesota Law Alumni Are Making A World of Difference BIN ZHAO ’97 SENIOR VP QUALCOMM CHINA THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA LAW SCHOOL MAGAZINE DEAN 2019–2020 Garry W. Jenkins BOARD OF ADVISORS DIRECTOR OF Gary J. Haugen ’74, Chair COMMUNICATIONS Michelle A. Miller ’86, Chair-Elect Mark A. Cohen Daniel W. McDonald ’85, Immediate Past Chair Ann M. Anaya ’93 EDITOR AND WRITER Joseph M. Barbeau ’81 Jeff Johnson Jeanette M. Bazis ’92 Sitso W. Bediako ’08 ASSISTANT DIRECTOR Amy L. Bergquist ’07 OF COMMUNICATIONS Karin J. Birkeland ’87 Monica Wittstock Rachel S. Brass ’01 Joshua L. Colburn ’07 COMMUNICATIONS Coré S. Cotton ’89 SPECIALIST Barbara Jean D’Aquila ’79 Luke Johnson The Honorable Natalie E. Hudson ’82 Rachel C. Hughey ’03 Ronald E. Hunter ’78 DIRECTOR OF Nora L. Klaphake ’94 ADVANCEMENT Greg J. Marita ’91 David Jensen Ambassador Tom McDonald ’79 Christine L. Meuers ’83 DIRECTOR OF Michael T. Nilan ’79 ALUMNI RELATIONS Pamela F. Olson ’80 AND ANNUAL GIVING Stephen P. Safranski ’97 Elissa Ecklund Chaffee Michael L. Skoglund ’01 James H. Snelson ’97 Michael P. Sullivan Jr. ’96 CONTRIBUTING Bryn R. Vaaler ’79 Minnesota Law is a general WRITERS Renae L. Welder ’96 interest magazine published Kevin Coss Emily M. Wessels ’14 in the fall and spring of the Kathy Graves Wanda Young Wilson ’79 academic year for the Ryan Greenwood University of Minnesota Law Mike Hannon ’98 School community of alumni, Chuck Leddy friends, and supporters. -

Minnesota's Scandinavian Political Legacy

Minnesota’s Scandinavian Political Legacy by Klas Bergman In 1892, Minnesota politics changed, for good. In that break-through year, Norwegian-born, Knute Nelson was elected governor of Minnesota, launching a new era with immigrants and their descendants from the five Nordic countries in leadership positions, forming a new political elite that has reshaped the state’s politics. The political story of the Scandinavian immigrants in Minnesota is unique. No other state can show a similar political involvement, although there are examples of Scandinavian political leaders in other states. “Outside of the Nordic countries, no other part of the world has been so influenced by Scandinavian activities and ambitions as Minnesota,” Uppsala University professor Sten Carlsson once wrote.1 Their imprint has made Minnesota the most Scandinavian of all the states, including in politics. These Scandinavian, or Nordic, immigrants from Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, and Sweden created a remarkable Scandinavian political legacy that has shaped Minnesota politics in a profound way and made it different from other states, while also influencing American politics beyond Minnesota. Since 1892, the Scandinavians and their descendants have been at the forefront of every phase of Minnesota’s political history. All but five of Minnesota’s twenty-six governors during the following 100 years have been Scandinavians—mostly Swedes and Norwegians, but also a Finland-Swede and a Dane, representing all political parties, although most of them— twelve—were Republicans. Two of them were talked about as possible candidates for the highest office in the land, but died young—John Governor Knute Nelson. Vesterheim Archives. -

Brought to You by These Sponsors

The Globe Saturday, September 8, 2018 1 KING TURKEY DAY BROUGHT TO YOU BY THESE SPONSORS AmeriGas • Avera Medical Group Worthington • Bedford Industries • Bedford Technology BTU Heating, Cooling & Plumbing • City of Worthington • Comfort Suites Cooperative Energy Company • Dan’s Electric • Dingmann Funeral Home • Doll Distributing Duininck Inc. • ECHO Electric Supply & Fasteners • Family Dentistry • Fareway • First State Bank SW Fulda Area Credit Union • Graham Tire Company • Ground Round Grill & Bar • RE/MAX Premier Realty Hedeen, Hughes & Wetering • Henderson Financial & Insurance Services • Hickory Lodge Bar & Grill Highland Manufacturing • Holiday Inn Express & Suites • Hy-Vee Food Store • JBS Jessica Noble State Farm • KM Graphics • Malters Shepherd & Von Holtum • Marthaler Automotive McDonalds • Merck Animal Health • Minnesota Energy Resources • Nickel and Associates Insurance Nienkerk Construction • Nobles Co-op Electric • Nobles County Implement Panaderia Mi Tierra Bakery • Pepsi Cola Bottling Co. • Prairie Holdings Group Quality Refrigerated Services • Radio Works • Rolling Hills Bank • Ron’s Repair Inc. • Runnings Sanford Worthington • Smith Trucking • State Farm Insurance - Jason Vote • Sterling Drug The Daily Apple • The Globe • Wells Fargo Bank • Worthington Convention & Visitors Bureau Worthington Electric • Worthington Elk’s Lodge Worthington Federal Savings Bank • Worthington Footwear & Repair Worthington Optimist Club • Worthington Noon Kiwanis Worthington Public Utilities LET’S GO 2 Saturday, September 8, 2018 KING TURKEY DAY The Globe 2018 SCHEDULE OF EVENTS Thursday, Sept. 13 parking lot 2 p.m. — Grand Parade, 10th Street 4:30 p.m. — Trojan Cross 8 a.m. to 2 p.m. — Smokin’ Country at former Prairie View Gobbler Cook-Off, Ninth Street 3:30 p.m. — Smokin’ Gobbler Cook-Off Awards Ceremony, property 9 a.m. -

No.2 of Rffiert J. SHERAN

MINNESOTA JUSTICES SERIES No.2 THE PR(ffSSlflJAL CAREER OF RffiERT J. SHERAN VOLUME 1 LIFE LEGAL AND JUDICIAL CAREER ST . PAUL i 982 -- . __..__._._----_.- .._- .- -~ -~---------- - ..- __ ._---_._..- -_ -.-------.-.._ =-"_.-"='---""".=.-••.= -====:=--- VOLUME 1 LIFE LEGAL AND JUDICIAL CAREER Table of Contents Acknowledgement i Introduction ii CHAPTER 1 Biographical Information A. Biography 1 B. Amicus Curiae 7 C. Law and Legislative Career 1. Poster for Former Lt. Governor 10 2. Voting Advertisment 11 3. Head of Bar Association 12 CHAPTER 2 Associate Justice of the Minnesota Supreme Court 1963-1970 A. Selected Letters on Appointment 1. Byron G. Allen-Democratic National Committeeman; Candidate for Governor, Minnesota 13 2. Elmer L. Anderson-Governor of Minnesota 14 3. Harry A. Blackmun-Attorney at Law, Minnesota; Judge, U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals 15 4. Val Bjornson-Minnesota State Treasurer 16 5. Lyman A. Brink~Judge, District Court, Minnesota, Ninth District 17 6. Thomas Conlin-Esquire 18 7. Marty Crowe-Classmate 19 8. Edward J. Devitt-Judge, U.S. District Court 21 9. Clement De Muth-Pastor; Missionary Korea 22 10. George D. Erickson-Judge, District Court \ Hinnesota, Ninth District 23 11. Edward Fitzgerald-Bishop of Winona 24 12. Donald M. Fraser-U.S. Congressman (currently Mayor of Minneapolis) 25 13. Kelton Gage-Esquire 26 14. Edward J. Gavin-Esquire 27 15. Leonard L. Harkness-State 4-H Club Leader; Agricultural Professor, University of Minnesota 28 16. Rex H. Hill-Mayor of Hankato 29 17., Fred Hughes-Esquire; Regent of University of Minnesota 30 18. Hubert H. Humphrey-U.S. -

The Church of St

The Church of St. George THE FOURTH SUNDAY IN ORDINARY TIME • FEBRUARY 3, 2019 Mass Schedule/Sacramental Life THE CHURCH OF ST. GEORGE Church and Parish Office Established 1916 133 North Brown Road • Long Lake, MN 55356 Weekend Masses: Pastor Phone: (952) 473-1247 • Fax: (952) 404-0129 Saturday: 4:00 pm Fr. Mark Juettner (952) 473-1247 x 104 Office Hours: Tues/Wed/Thurs 9-3pm & Fri , 9-1pm Sunday: 9:15am Fr. Juettner- After Hours: [email protected] Office E-mail: [email protected] Mass in Spanish: EMERGENCY LINE TO FR. JUETTNER: www.stgeorgelonglake.org Sunday: 5:00 pm To report an after hour medical emergency or death, call (952) 473-1247 X 150. Weekday & Holy Day Masses: Consult schedule inside bulletin. For information about the Knights of Columbus, please contact Reconciliation: Ed Rundle at 952-473-9565. Individual: Tues. 9am; First Fridays 9am; Sat. 3:00pm-3:45pm & 5:15pm; For information about the Women’s Council, please contact President Sun. 8:30am-9am Shannon Banks at 612-554-3274. Adoration: Monday-Friday, Sunday evenings Call: Jean Kottemann (952) 471-7485 Baptism, Anointing of the Sick, Marriage: Contact the Parish Office (952) 473-1247 Pastoral visits to the sick & home-bound: The Feast of St. Blaise: Contact the Parish Office The Blessing of the Throats Parish Staff (952-473-1247) Deacon: Bruce Bowen (612) 298-4867 [email protected] Secretary: Sara Dore ext100 Latino Ministry: Melba Reyes ext106 Faith Formation: Christina Ruiz ext102 Bookkeeper: Lynn Johnston ext103 Music: Kelly Kadlec ext105 Head of Bldg., Grounds & Supplies Mike Dombeck - Cell (612) 716-7107 Bldg.