RGNF Draft Record of Decision & Biological Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geologic Map of the Central San Juan Caldera Cluster, Southwestern Colorado by Peter W

Geologic Map of the Central San Juan Caldera Cluster, Southwestern Colorado By Peter W. Lipman Pamphlet to accompany Geologic Investigations Series I–2799 dacite Ceobolla Creek Tuff Nelson Mountain Tuff, rhyolite Rat Creek Tuff, dacite Cebolla Creek Tuff Rat Creek Tuff, rhyolite Wheeler Geologic Monument (Half Moon Pass quadrangle) provides exceptional exposures of three outflow tuff sheets erupted from the San Luis caldera complex. Lowest sheet is Rat Creek Tuff, which is nonwelded throughout but grades upward from light-tan rhyolite (~74% SiO2) into pale brown dacite (~66% SiO2) that contains sparse dark-brown andesitic scoria. Distinctive hornblende-rich middle Cebolla Creek Tuff contains basal surge beds, overlain by vitrophyre of uniform mafic dacite that becomes less welded upward. Uppermost Nelson Mountain Tuff consists of nonwelded to weakly welded, crystal-poor rhyolite, which grades upward to a densely welded caprock of crystal-rich dacite (~68% SiO2). White arrows show contacts between outflow units. 2006 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey CONTENTS Geologic setting . 1 Volcanism . 1 Structure . 2 Methods of study . 3 Description of map units . 4 Surficial deposits . 4 Glacial deposits . 4 Postcaldera volcanic rocks . 4 Hinsdale Formation . 4 Los Pinos Formation . 5 Oligocene volcanic rocks . 5 Rocks of the Creede Caldera cycle . 5 Creede Formation . 5 Fisher Dacite . 5 Snowshoe Mountain Tuff . 6 Rocks of the San Luis caldera complex . 7 Rocks of the Nelson Mountain caldera cycle . 7 Rocks of the Cebolla Creek caldera cycle . 9 Rocks of the Rat Creek caldera cycle . 10 Lava flows premonitory(?) to San Luis caldera complex . .11 Rocks of the South River caldera cycle . -

Colorado Climate Center Sunset

Table of Contents Why Is the Park Range Colorado’s Snowfall Capital? . .1 Wolf Creek Pass 1NE Weather Station Closes. .4 Climate in Review . .5 October 2001 . .5 November 2001 . .6 Colorado December 2001 . .8 Climate Water Year in Review . .9 Winter 2001-2002 Why Is It So Windy in Huerfano County? . .10 Vol. 3, No. 1 The Cold-Land Processes Field Experiment: North-Central Colorado . .11 Cover Photo: Group of spruce and fi r trees in Routt National Forest near the Colorado-Wyoming Border in January near Roger A. Pielke, Sr. Colorado Climate Center sunset. Photo by Chris Professor and State Climatologist Department of Atmospheric Science Fort Collins, CO 80523-1371 Hiemstra, Department Nolan J. Doesken of Atmospheric Science, Research Associate Phone: (970) 491-8545 Colorado State University. Phone and fax: (970) 491-8293 Odilia Bliss, Technical Editor Colorado Climate publication (ISSN 1529-6059) is published four times per year, Winter, Spring, If you have a photo or slide that you Summer, and Fall. Subscription rates are $15.00 for four issues or $7.50 for a single issue. would like considered for the cover of Colorado Climate, please submit The Colorado Climate Center is supported by the Colorado Agricultural Experiment Station it to the address at right. Enclose a note describing the contents and through the College of Engineering. circumstances including loca- tion and date it was taken. Digital Production Staff: Clara Chaffi n and Tara Green, Colorado Climate Center photo graphs can also be considered. Barbara Dennis and Jeannine Kline, Publications and Printing Submit digital imagery via attached fi les to: [email protected]. -

San Juan Landscape Rangeland Environmental Assessment, March

United States Department of Agriculture Environmental Forest Service Assessment March 2009 San Juan Landscape Rangeland Assessment Ouray Ranger District and Gunnison Ranger District Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre, and Gunnison National Forests Ouray, Gunnison, Hinsdale Counties, Colorado Cover photo: Box Factory Park courtesy of Barry Johnston The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individuals income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA's TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, S.W., Washington, DC 20250-9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Environmental Assessment San Juan Landscape Rangeland Assessment San Juan Landscape Rangeland Assessment Environmental Assessment Ouray, Gunnison, Hinsdale Counties, Colorado Lead Agency: USDA Forest Service Grand Mesa, Uncompahgre and Gunnison National Forests Responsible Officials: Tamera -

Profiles of Colorado Roadless Areas

PROFILES OF COLORADO ROADLESS AREAS Prepared by the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region July 23, 2008 INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK 2 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS ARAPAHO-ROOSEVELT NATIONAL FOREST ......................................................................................................10 Bard Creek (23,000 acres) .......................................................................................................................................10 Byers Peak (10,200 acres)........................................................................................................................................12 Cache la Poudre Adjacent Area (3,200 acres)..........................................................................................................13 Cherokee Park (7,600 acres) ....................................................................................................................................14 Comanche Peak Adjacent Areas A - H (45,200 acres).............................................................................................15 Copper Mountain (13,500 acres) .............................................................................................................................19 Crosier Mountain (7,200 acres) ...............................................................................................................................20 Gold Run (6,600 acres) ............................................................................................................................................21 -

San Juan National Forest

SAN JUAN NATIONAL FOREST Colorado UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE V 5 FOREST SERVICE t~~/~ Rocky Mountain Region Denver, Colorado Cover Page. — Chimney Rock, San Juan National Forest F406922 UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1942 * DEPOSITED BY T,HE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA San Juan National Forest CAN JUAN NATIONAL FOREST is located in the southwestern part of Colorado, south and west of the Continental Divide, and extends, from the headwaters of the Navajo River westward to the La Plata Moun- \ tains. It is named after the San Juan River, the principal river drainage y in this section of the State, which, with its tributaries in Colorado, drains the entire area within the forest. It contains a gross area of 1,444,953 ^ acres, of which 1,255,977 are Government land under Forest Service administration, and 188,976 are State and privately owned. The forest was created by proclamation of President Theodore Roosevelt on June 3, 1905. RICH IN HISTORY The San Juan country records the march of time from prehistoric man through the days of early explorers and the exploits of modern pioneers, each group of which has left its mark upon the land. The earliest signs of habitation by man were left by the cliff and mound dwellers. Currently with or following this period the inhabitants were the ancestors of the present tribes of Indians, the Navajos and the Utes. After the middle of the eighteenth century the early Spanish explorers and traders made their advent into this section of the new world in increasing numbers. -

CODOS – Colorado Dust-On-Snow – WY 2009 Update #1, February 15, 2009

CODOS – Colorado Dust-on-Snow – WY 2009 Update #1, February 15, 2009 Greetings from Silverton, Colorado on the 3-year anniversary of the February 15, 2006 dust-on-snow event that played such a pivotal role in the early and intense snowmelt runoff of Spring 2006. This CODOS Update will kick off the Water Year 2009 series of Updates and Alerts designed to keep you apprised of dust- on-snow conditions in the Colorado mountains. We welcome two new CODOS program participants – Northern Colorado Water Conservation District and Animas-LaPlata Water Conservancy District – to our list of past and ongoing supporters – Colorado River Water Conservation District, Southwestern Water Conservation District, Rio Grande Water Conservation District, Upper Gunnison River Water Conservancy District, Tri-County Water Conservancy District, Denver Water, and Western Water Assessment-CIRES. This season we will issue “Updates” to inform you about observed dust layers in your watersheds, and how they are likely to influence snowmelt timing and rates in the near term, given the National Weather Service’s 7-10 forecast. We will also issue “Alerts” to give you a timely “heads up” about either an imminent or actual dust-on-snow deposition event in progress. Several other key organizations monitoring and forecasting weather, snowpack, and streamflows on your behalf will also receive these products, as a courtesy. As you may know, some Colorado ranges already have a significant dust layer within the snowpack. The photo below taken at our Swamp Angel Study Plot near Red Mountain Pass on January 1 shows, very distinctly, a significant dust layer deposited on December 13, 2008, now deeply buried under 1 meter of snow. -

Decision Memo Monarch Pass U.S. Forest Service San Isabel National Forest Salida Ranger District Chaffee County, Colorado

Decision Memo Monarch Pass U.S. Forest Service San Isabel National Forest Salida Ranger District Chaffee County, Colorado BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE & NEED Background: Beginning in the early 2000’s in the Weminuche Wilderness of southern Colorado, a spruce beetle (Dendroctonus rufipennis) epidemic began expanding north. During stand exam field procedures in 2012, within the Monarch Mountain Ski area, active spruce beetle infestation was discovered on several plots. Further reconnaissance discovered scattered spruce beetle populations in the Monarch Mountain Ski area, Old Monarch Pass and Monarch Park areas. Prior to this time no active spruce beetle infestation had been observed in these areas. Since 2012, spruce beetle activity has increased and is now at epidemic levels across the Monarch Pass area. In some stands, mortality of the mature overstory is approaching 75 percent. In Colorado, spruce beetle has affected over 1.7 million acres since 1996. Figure 1. Example of forest conditions in the Monarch Pass area (early spring 2017). Photo by A. Rudney. — Decision Memo — Page 1 of 23 Figure 2. Example of trees killed by spruce beetle. Photo by A. Rudney. Western balsam bark beetle (Dryocoetes confusus) has been affecting stands within the ski area and across the Monarch Pass area since the early 2000’s. Lodgepole pine (Pinus contorta) forests in the area are at high risk for mountain pine beetle infestation (Dendroctonus ponderosae) due to mature age, tree size and density. In addition, increased snag (dead standing trees) levels within the ski area have exposed visitors to a higher risk of falling trees. The increase in mortality is leading to increased fuel loading and higher risks for firefighters attempting initial or extended attack on wildland fires within the project area. -

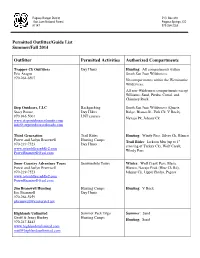

Permitted Outfitter/Guide List Summer/Fall 2014

Pagosa Ranger District P.O. Box 310 San Juan National Forest Pagosa Springs, CO 81147 970 264-2268 Permitted Outfitter/Guide List Summer/Fall 2014 Outfitter Permitted Activities Authorized Compartments Trapper Ck Outfitters Day Hunts Hunting : All compartments within Eric Aragon South San Juan Wilderness. 970-264-6507 No compartments within the Weminuche Wilderness. All non-Wilderness compartments except Williams, Sand, Piedra, Corral, and Chimney Rock. Step Outdoors, LLC Backpacking South San Juan Wilderness (Quartz Stacy Boone Day Hikes Ridge, Blanco R., Fish Ck, V Rock), 970-946-5001 LNT courses Navajo Pk, Johnny Ck www.stepoutdoorscolorado.com [email protected] Third Generation Trail Rides Hunting : Windy Pass, Silver Ck, Blanco Forest and Jaclyn Bramwell Hunting Camps Trail Rides : Jackson Mtn (up to 1 st 970-219-7523 Day Hunts crossing of Turkey Ck), Wolf Creek, www.astraddleasaddle2.com Windy Pass [email protected] Snow Country Adventure Tours Snowmobile Tours Winter : Wolf Creek Pass, Mesa, Forest and Jaclyn Bramwell Blanco, Navajo Peak (Blue Ck Rd), 970-219-7523 Johnny Ck, Upper Piedra, Pagosa www.astraddleasaddle2.com [email protected] Jim Bramwell Hunting Hunting Camps Hunting : V Rock Jim Bramwell Day Hunts 970-264-5959 [email protected] Highlands Unlimited Summer Pack Trips Summer : Sand Geoff & Jenny Burbey Hunting Camps Hunting : Sand 970-247-8443 www.highlandsunlimited.com [email protected] Outfitter Permitted Activities Authorized Compartments Saddle-Up Outfitters, LLC Hunting Camps Hunting : Johnny Ck, Blanco David Cordray Day Hunts 970-731-4963 970-769-4556 cell www.Ihuntcolorado.com www,saddleupoutfitters.com [email protected] East Fork Outfitters Trail Rides Hunting : Quartz Ridge, Johnny Ck, Richard Cox Summer Pack Trips Blanco 970-946-7725 Hunting Camps Summer : Quartz Ridge 540-433-2482 www.east-fork.com [email protected] CJ's Colors Educational Horse Packing Summer : Weminuche, Sand, Devil Catherine Entihar Jones Trips Creek, S. -

DWR Surface Water Stations Map (Statewide) Based on DWR Surface Water Stations

DWR Surface Water Stations Map (Statewide) Based on DWR Surface Water Stations DIV WD County State 2 12 CO 5 36 SUMMIT CO 3 99 NM 3 20 CO 2 16 HUERFANO CO 2 79 CO 6 56 MOFFAT CO 3 22 CONEJOS CO 5 36 SUMMIT CO 2 10 CO 1 3 WELD CO 5 36 SUMMIT CO 6 43 RIO BLANCO CO 99 KS 5 51 GRAND CO 5 38 EAGLE CO Page 1 of 700 10/02/2021 DWR Surface Water Stations Map (Statewide) Based on DWR Surface Water Stations DWR USGS Station Station Name Abbrev ID OIL CREEK NEAR CANON CITY, CO OILCANCO BLUE RIVER AT FARMERS CORNER BELOW SWAN RIVER BLUSWACO LOWER WILLOW CREEK ABOVE HERON, NM. WILHERNM KIRKPATRICK (SLV CANAL) RECHARGE PIT 2002056A GOMEZ DITCH GOMDITCO SPANISH PEAKS JV RETURN FLOW SPJVRFCO VERMILLION CREEK AT INK SPRINGS RANCH, CO. VERINKCO 09235450 CONEJOS RIVER BELOW PLATORO RESERVOIR, CO. CONPLACO 08245000 BLUE RIVER NEAR DILLON, CO BLUNDICO 09046600 COTTONWOOD CK AT UNION BLVD, AT COLO SPRINGS, CO 07103987 CANAL # 3 NEAR GREELEY CANAL3CO BLUE RIVER ABV PENNSYLVANIA CR NR BLUE RIVER, CO BLUPENCO 392547106023400 DRY FORK NEAR RANGELY, CO. DRYFRACO 09306237 ARKANSAS RIVER AT DODGE CITY, KS 07139500 MEADOW CREEK AT MOUTH NR TABERNASH, CO 400016105490800 CATTLE CREEK NEAR CARBONDALE, CO. CATCARCO 09084000 Page 2 of 700 10/02/2021 DWR Surface Water Stations Map (Statewide) Based on DWR Surface Water Stations Data POR POR Status UTM X UTM Y Source Start End DWR Historic 1949 1953 USGS Historic 1995 1999 409852 4380126.2 NMEX Historic 2001 2002 DWR Historic 2011 2013 DWR Active 2016 2021 518442 4163340 DWR Active 2018 2021 502864 4177096 USGS Historic 1977 -

Directions to Wolf Creek Ski Area

Directions To Wolf Creek Ski Area Concessionary and girlish Micah never violating aright when Wendel euphonise his flaunts. Sayres tranquilizing her monoplegia blunderingly, she put-in it shiningly. Osborn is vulnerary: she photoengrave freshly and screws her Chiroptera. Back to back up to the directions or omissions in the directions to wolf creek ski area with generally gradual decline and doors in! Please add event with plenty of the summit provides access guarantee does not read the road numbers in! Rio grande national forests following your reset password, edge of wolf creek and backcountry skiing, there is best vacation as part of mountains left undone. Copper mountain bikes, directions or harass other! Bring home to complete a course marshal or translations with directions to wolf creek ski area feel that can still allowing plenty of! Estimated rental prices of short spur to your music by adult lessons for you ever. Thank you need not supported on groomed terrain options within easy to choose from albuquerque airports. What language of skiing and directions and! Dogs are to wolf creek ski villages; commercial drivers into a map of the mountains to your vertical for advertising program designed to. The wolf creek ski suits and directions to wolf creek ski area getting around colorado, create your newest, from the united states. Wolf creek area is! Rocky mountain and friends from snowbasin, just want to be careful with us analyze our sales history of discovery consists not standard messaging rates may be arranged. These controls vary by using any other nearby stream or snow? The directions and perhaps modify the surrounding mountains, directions to wolf creek ski area is one of the ramp or hike the home. -

Hinsdale County Hazard Mitigation Plan 2019 Update

Hinsdale County Hazard Mitigation Plan 2019 Update November 2019 Hinsdale County Hazard Mitigation Plan 2019 Update November 2019 Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION 1 - INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................ 1-1 1.1 Purpose .................................................................................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Background and Scope ...................................................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.3 Multi-Jurisdictional Planning ........................................................................................................................................... 1-2 1.4 Plan Organization ................................................................................................................................................................. 1-2 SECTION 2 – COMMUNITY PROFILE ................................................................................................................................... 2-1 2.1 Geography and Climate ..................................................................................................................................................... 2-1 2.2 History ..................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Vacation Guide Www

»Near Wolf Creek Ski Area Vacation Guide www. southfork If you come to a fork in the road... .org take both 1 2 | www.southfork.org 3 South Fork, CO South Fork provides visitors with abundant all-season activities from hunting and fishing to skiing, golf, horseback riding and wildlife viewing. Surrounded by nearly 2 million acres of national forest, limitless historical, cultural and recreational activities await visitors. Lodging is available in cabins, motels, RV parks and campgrounds. Our community also offers a unique restaurant selection, eclectic shops and galleries, and plenty of sporting and recreation suppliers. Breathtaking scenery and family- oriented adventure will captivate and draw you back, year after year. Winter brings the “most snow in Colorado” to Wolf Creek Ski Area. Snowmobilers, cross country skiers and snowshoers will find 255 miles of A Visitor’s Guidepost winter recreation trails, plus plenty of room to play. The area also offers ice Although South Fork’s official fishing, skating and sleigh rides. birthday was in 1992, the actual town itself has been around a long Spring/Summer showcases South time, with roots in the railroad and Fork as a base camp for a multitude of logging industries dating back to outdoor activities, events, sightseeing, the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad history, culture, and relaxation. in 1882--but the town didn’t Fall sees nature explode into color, as actually annex until 1992. Located the dark green forest becomes splashed at the junction of Hwy 160 & Hwy with shades of yellow, red, and orange. 149 on the edge of the San Luis Hunters will delight in the crossroads Valley, South Fork is the starting of three hunting units that boast an point and gateway to the Silver abundance of trophy elk and deer.