Drug Treatment in Acute Porphyria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clinical and Biochemical Characteristics and Genotype – Phenotype Correlation in Finnish Variegate Porphyria Patients

European Journal of Human Genetics (2002) 10, 649 – 657 ª 2002 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 1018 – 4813/02 $25.00 www.nature.com/ejhg ARTICLE Clinical and biochemical characteristics and genotype – phenotype correlation in Finnish variegate porphyria patients Mikael von und zu Fraunberg*,1, Kaisa Timonen2, Pertti Mustajoki1 and Raili Kauppinen1 1Department of Medicine, Division of Endocrinology, University Central Hospital of Helsinki, Biomedicum Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland; 2Department of Dermatology, University Central Hospital of Helsinki, Biomedicum Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland Variegate porphyria (VP) is an inherited metabolic disease resulting from the partial deficiency of protoporphyrinogen oxidase, the penultimate enzyme in the heme biosynthetic pathway. We have evaluated the clinical and biochemical outcome of 103 Finnish VP patients diagnosed between 1966 and 2001. Fifty-two per cent of patients had experienced clinical symptoms: 40% had photosensitivity, 27% acute attacks and 14% both manifestations. The proportion of patients with acute attacks has decreased dramatically from 38 to 14% in patients diagnosed before and after 1980, whereas the prevalence of skin symptoms had decreased only subtly from 45 to 34%. We have studied the correlation between PPOX genotype and clinical outcome of 90 patients with the three most common Finnish mutations I12T, R152C and 338G?C. The patients with the I12T mutation experienced no photosensitivity and acute attacks were rare (8%). Therefore, the occurrence of photosensitivity was lower in the I12T group compared to the R152C group (P=0.001), whereas no significant differences between the R152C and 338G?C groups could be observed. Biochemical abnormalities were significantly milder suggesting a milder form of the disease in patients with the I12T mutation. -

Ex Vivo Gene Therapy: a “Cultured” Surgical Approach to Curing Inherited Liver Disease

Mini Review Open Access J Surg Volume 10 Issue 3 - March 2019 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Joseph B Lillegard DOI: 10.19080/OAJS.2019.10.555788 Ex Vivo Gene Therapy: A “Cultured” Surgical Approach to Curing Inherited Liver Disease Caitlin J VanLith1, Robert A Kaiser1,2, Clara T Nicolas1 and Joseph B Lillegard1,2,3* 1Department of Surgery, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA 2Midwest Fetal Care Center, Children’s Hospital of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, USA 3Pediatric Surgical Associates, Minneapolis, MN, USA Received: February 22, 2019; Published: March 21, 2019 *Corresponding author: Joseph B Lillegard, Midwest Fetal Care Center, Children’s Hospital of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA and Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, USA Introduction Inborn errors of metabolism (IEMs) are a group of inherited diseases caused by mutations in a single gene [1], many of which transplant remains the only curative option. Between 1988 and 2018, 12.8% of 17,009 pediatric liver transplants in the United States(see were primarily due to an inherited liver). disease. are identified in Table 1. Though individually rare, combined incidence is about 1 in 1,000 live births [2]. While maintenance www.optn.transplant.hrsa.gov/data/ Table 1: List of 35 of the most common Inborn Errors of Metabolism. therapies exist for some of these liver-related diseases, Inborn Error of Metabolism Abbreviation Hereditary Tyrosinemia type 1 HT1 Wilson Disease Wilson Glycogen Storage Disease 1 GSD1 Carnitine Palmitoyl Transferase Deficiency Type 2 CPT2 Glycogen Storage -

Variegate Porphyria with Coexistent Decrease in Porphobilinogen Deaminase Activity

Acta Derm Venereol 2001; 81: 356–359 CLINICAL REPORT Variegate Porphyria with Coexistent Decrease in Porphobilinogen Deaminase Activity GEORG WEINLICH1, MANFRED O. DOSS2, NORBERT SEPP1 and PETER FRITSCH1 1Department of Dermatology, University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria and 2Department of Clinical Biochemistry, University of Marburg, Marburg, Germany Variegate porphyria is a rare disease caused by a de ciency of deaminase. Its activity is reduced by about 50%, resulting in protoporphyrinogen oxidase. In most cases, the clinical ndings are varying degrees of overproduction and increased urinary excre- a combination of systemic symptoms similar to those occurring in tion of delta-aminolaevulinic acid (ALA) and PBG. In AIP, acute intermittent porphyria and cutaneous lesions indistinguishable skin changes are absent, but patients suVer from episodic from those of porphyria cutanea tarda. We report on a 24-year- central or peripheral nervous system and/or psychiatric symp- old woman with variegate porphyria who, after intake of lynestrenol, toms, or acute attacks of abdominal pain (2, 4). developed typical cutaneous lesions but no viscero-neurological Variegate porphyria (VP), a rare autosomal-dominant hep- symptoms. The diagnosis was based on the characteristic urinary atic porphyria due to a de ciency of protoporphyrinogen coproporphyrin and faecal protoporphyrin excretion patterns, and (PROTO) oxidase, the related gene (PPOX ) for which has the speci c peak of plasma uorescence at 626 nm in spectro uor- been located to chromosome 1q22-23 (5, 6), is characterized ometry. Biochemical analysis revealed that most of the family by both acute neurological symptoms as in AIP and skin members, though free of clinical symptoms, excrete porphyrin lesions indistinguishable from PCT; it is thus also termed metabolites in urine and stool similar to variegate porphyria, mixed porphyria (2, 7, 8). -

Demystification of Chester Porphyria: a Nonsense Mutation in the Porphobilinogen Deaminase Gene

Physiol. Res. 55 (Suppl. 2): S137-S144, 2006 Demystification of Chester Porphyria: A Nonsense Mutation in the Porphobilinogen Deaminase Gene *P. POBLETE-GUTIÉRREZ1, *T. WIEDERHOLT2, 3, A. MARTINEZ-MIR4, H. F. MERK2, J. M. CONNOR5, A. M. CHRISTIANO4, 6, J. FRANK1,2,3 1Department of Dermatology, University Hospital Maastricht, The Netherlands, 2Department of Dermatology and Allergology and 3Porphyria Center, University Hospital of the RWTH Aachen, Germany, 4Department of Dermatology, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA, 5Institute of Medical Genetics, Yorkhill Hospitals, Glasgow, Scotland, 6Department of Genetics and Develop- ment, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA Received October 4, 2005 Accepted March 24, 2006 Summary The porphyrias arise from predominantly inherited catalytic deficiencies of specific enzymes in heme biosynthesis. All genes encoding these enzymes have been cloned and several mutations underlying the different types of porphyrias have been reported. Traditionally, the diagnosis of porphyria is made on the basis of clinical symptoms, characteristic biochemical findings, and specific enzyme assays. In some cases however, these diagnostic tools reveal overlapping findings, indicating the existence of dual porphyrias with two enzymes of heme biosynthesis being deficient simultane- ously. Recently, it was reported that the so-called Chester porphyria shows features of both variegate porphyria and acute intermittent porphyria. Linkage analysis revealed a novel chromosomal locus on chromosome 11 for the underly- ing genetic defect in this disease, suggesting that a gene that does not encode one of the enzymes of heme biosynthesis might be involved in the pathogenesis of the porphyrias. After excluding candidate genes within the linkage interval, we identified a nonsense mutation in the porphobilinogen deaminase gene on chromosome 11q23.3, which harbors the mutations causing acute intermittent porphyria, as the underlying genetic defect in Chester porphyria. -

A High Urinary Urobilinogen / Serum Total Bilirubin Ratio Reported in Abdominal Pain Patients Can Indicate Acute Hepatic Porphyria

A High Urinary Urobilinogen / Serum Total Bilirubin Ratio Reported in Abdominal Pain Patients Can Indicate Acute Hepatic Porphyria Chengyuan Song Shandong University Qilu Hospital Shaowei Sang Shandong University Qilu Hospital Yuan Liu ( [email protected] ) Shandong University Qilu Hospital https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4991-552X Research Keywords: acute hepatic porphyria, urinary urobilinogen, serum total bilirubin Posted Date: June 14th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-587707/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/10 Abstract Background: Due to its variable symptoms and nonspecic laboratory test results during routine examinations, acute hepatic porphyria (AHP) has always been a diagnostic dilemma for physicians. Misdiagnoses, missed diagnoses, and inappropriate treatments are very common. Correct diagnosis mainly depends on the detection of a high urinary porphobilinogen (PBG) level, which is not a routine test performed in the clinic and highly relies on the physician’s awareness of AHP. Therefore, identifying a more convenient indicator for use during routine examinations is required to improve the diagnosis of AHP. Results: In the present study, we retrospectively analyzed laboratory examinations in 12 AHP patients and 100 patients with abdominal pain of other causes as the control groups between 2015 and 2021. Compared with the control groups, AHP patients showed a signicantly higher urinary urobilinogen level during the urinalysis (P < 0.05). However, we showed that the higher urobilinogen level was caused by a false- positive result due to a higher level of urine PBG in the AHP patients. Hence, we used serum total bilirubin, an upstream substance of urinary urobilinogen synthesis, for calibration. -

Photodermatoses in Children

Review article Photodermatoses in children Siti Nurani Fauziah, Wresti Indriatmi, Lili Legiawati Department of Dermatology & Venereology Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Indonesia, dr. Cipto Mangunkusumo Hospital, Jakarta, Indonesia E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Photodermatoses cover the skin’s abnormal reactions to sunlight, usually to its ultraviolet (UV) component or visible light. Etiologically, photodermatoses can be classified into 4 categories: (1) immunologically mediated photodermatoses (idiopathic photodermatoses); (2) drug- or chemical-induced photosensitivity; (3) hereditary photodermatoses; and (4) photoaggravated dermatoses. The incidence of photodermatoses in the pediatric population is much lower than in adults. Polymorphous light eruption (PMLE) is the most common form of photodermatoses in children, followed by erythropoietic protoporphyria. Early diagnosis and investigations should be performed to avoid long-term complications. Photoprotection is the mainstay of photodermatoses management, including use of physical protection and sunscreen. Keywords: children, photodermatoses, photoprotection, polymorphous light eruption. Background usually on the face, neck, extensor forearms, and hands. Early recognition of symptoms and early Photodermatoses is a term used to describe diagnosis is important to prevent complications 1 abnormal reactions of the skin to light, especially due to inadequate photoprotection. to ultraviolet (UV) radiation or visible light.1-3 Incidence of photodermatoses in children is lower This -

Biochemical Differentiation of the Porphyrias

Clinical Biochemistry, Vol. 32, No. 8, 609–619, 1999 Copyright © 1999 The Canadian Society of Clinical Chemists Printed in the USA. All rights reserved 0009-9120/99/$–see front matter PII S0009-9120(99)00067-3 Biochemical Differentiation of the Porphyrias J. THOMAS HINDMARSH,1,2 LINDA OLIVERAS,1 and DONALD C. GREENWAY1,2 1Division of Biochemistry, The Ottawa Hospital, and the 2Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Ottawa, 501 Smyth Road, Ottawa, Ontario K1H 8L6, Canada Objectives: To differentiate the porphyrias by clinical and biochem- vals for urine, fecal, and blood porphyrins and their ical methods. precursors in the various porphyrias and in normal Design and methods: We describe levels of blood, urine, and fecal porphyrins and their precursors in the porphyrias and present an subjects and have devised an algorithm for investi- algorithm for their biochemical differentiation. Diagnoses were es- gation of these diseases. Except for Porphyria Cuta- tablished using clinical and biochemical data. Porphyrin analyses nea Tarda (PCT), our numbers of patients in each were performed by high performance liquid chromatography. category of porphyria are small and therefore our Results and conclusions: Plasma and urine porphyrin patterns reference ranges for these should be considered were useful for diagnosis of porphyria cutanea tarda, but not the acute porphyrias. Erythropoietic protoporphyria was confirmed by approximate. erythrocyte protoporphyrin assay and erythrocyte fluorescence. Acute intermittent porphyria was diagnosed by increases in urine Materials and methods delta-aminolevulinic acid and porphobilinogen and confirmed by reduced erythrocyte porphobilinogen deaminase activity and nor- REAGENTS AND CHEMICALS mal or near-normal stool porphyrins. -

Conversion of Amino Acids to Specialized Products

Conversion of Amino Acids to Specialized Products First Lecture Second lecture Fourth Lecture Third Lecture Structure of porphyrins Porphyrins are cyclic compounds that readily bind metal ions (metalloporphyrins)—usually Fe2+ or Fe3+. Porphyrins vary in the nature of the side chains that are attached to each of the four pyrrole rings. - - Uroporphyrin contains acetate (–CH2–COO )and propionate (–CH2–CH2–COO ) side chains; Coproporphyrin contains methyl (–CH3) and propionate groups; Protoporphyrin IX (and heme) contains vinyl (–CH=CH2), methyl, and propionate groups Structure of Porphyrins Distribution of side chains: The side chains of porphyrins can be ordered around the tetrapyrrole nucleus in four different ways, designated by Roman numerals I to IV. Only Type III porphyrins, which contain an asymmetric substitution on ring D are physiologically important in humans. Physiologically important In humans Heme methyl vinyl 1) Four Pyrrole rings linked together with methenyle bridges; 2) Three types of side chains are attached to the rings; arrangement of these side chains determines the activity; 3) Asymmetric molecule 3) Porphyrins bind metal ions to form metalloporphyrins. propionyl Heme is a prosthetic group for hemoglobin, myoglobin, the cytochromes, catalase and trptophan pyrrolase Biosynthesis of Heme The major sites of heme biosynthesis are the liver, which synthesizes a number of heme proteins (particularly cytochrome P450), and the erythrocyte-producing cells of the bone marrow, which are active in hemoglobin synthesis. Heme synthesis occurs in all cells due to the requirement for heme as a prosthetic group on enzymes and electron transport chain. The initial reaction and the last three steps in the formation of porphyrins occur in mitochondria, whereas the intermediate steps of the biosynthetic pathway occur in the cytosol. -

The Little Imitator-Porphyria: a Neuropsychiatric Disorder

Journal ofNeurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry 1997;62:319-328 319 REVIEW J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry: first published as 10.1136/jnnp.62.4.319 on 1 April 1997. Downloaded from The little imitator-porphyria: a neuropsychiatric disorder Helen L Crimlisk Abstract Porphyria is derived from the Greek word por- Three common subtypes of porphyria phuros meaning purple. Protoporphyrin IX is give rise to neuropsychiatric disorders; the biologically active substance, an important acute intermittent porphyria, variegate feature of which is its metal binding capacity. porphyria, and coproporphyria. The sec- Both chlorophyll and haem are metallopor- ond two also give rise to cutaneous symp- phyrins and are involved in the processes of toms. Neurological or psychiatric energy capture and utilisation in animals and symptoms occur in most acute attacks, plants. The description of the porphyrins by and may mimc many other disorders. Nobel laureate Hans Fischer' in 1930 as: The diagnosis may be missed because it is "The compounds which make grass green not even considered or because of techni- and blood red." cal problems, such as sample collection indicates the central position of these sub- and storage, and interpretation of results. stances in the biological sciences. A negative screening test does not exclude The porphyrias are a heterogeneous group the diagnosis. Porphyria may be overrep- of overproduction diseases, resulting from resented in psychiatric populations, but genetically determined, partial deficiencies in the lack of control groups makes this haem biosynthetic enzymes. Their manifesta- Department of uncertain. The management of patients tions are broad and their relevance in neu- Neuropsychiatry, with porphyria and psychiatric symptoms ropsychiatric disorders may sometimes be Institute ofNeurology, causes considerable Queen Square, problems. -

Molecular Genetics of Variegate Porphyria in Finland

Department of Medicine, Division of Endocrinology University of Helsinki, Finland MOLECULAR GENETICS OF VARIEGATE PORPHYRIA IN FINLAND Mikael von und zu Fraunberg Academic dissertation To be presented with the permission of the Medical Faculty of the University of Helsinki, for public examination in Auditorium II, Haartmaninkatu 8, Biomedicum Helsinki, on March 22th 2003, at 12:00 noon Helsinki 2003 SUPERVISED BY Docent Raili Kauppinen, M.D., Ph.D. Department of Medicine Division of Endocrinology University of Helsinki Finland REVIEWED BY Professor Richard J. Hift, M.D., Ph.D. Department of Medicine Lennox Eales Porphyria Laboratory MRC/UCT Liver Research Centre University of Cape Town South Africa and Professor Eeva-Riitta Savolainen, M.D., Ph.D. Department of Clinical Chemistry University of Oulu Finland OFFICIAL OPPONENT: Docent Katriina Aalto-Setälä, M.D., Ph.D. Department of Medicine University of Tampere Finland © Mikael von und zu Fraunberg ISBN 952-91-5643-X (paperback) ISBN 952-10-0970-5 (pdf) http://ethesis.helsinki.fi Helsinki 2003 Yliopistopaino to my family CONTENTS SUMMARY............................................................................................................... 6 ORIGINAL PUBLICATIONS................................................................................... 8 ABBREVIATIONS.................................................................................................... 9 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................... 10 REVIEW -

Acute Intermittent Porphyria Antonio Dajer, MD; Louis Cooper, MD

CASE REPORT Acute Intermittent Porphyria Antonio Dajer, MD; Louis Cooper, MD A 34-year-old pregnant woman presented for evaluation of severe, persistent abdominal pain. Case A 34-year-old woman presented to the ED with severe, persistent abdomi- nal pain that had begun 18 days earlier. She was 7 weeks pregnant and had been seen in the same ED the day before. During that visit, ultra- sound had shown a single pregnancy of doubtful viability. Abdominal magnetic resonance imaging was normal. She was given multiple doses of hydromorphone. The discharge diagnosis was “missed abortion.” Since the onset of her pain, she had been hospitalized twice elsewhere, with no clear diagnosis to explain her pain. Treatment consisted of repeat doses of hydromorphone. During the second hospitalization, a sodium level of 109 mEq/L had been corrected with hypertonic saline, and a urinary tract infection (UTI) had been treated with cephalexin. Our patient had never experienced similar abdomi- nal pain. Her medical history included depression and asthma. Her family history was notable for an aunt who had died of lung cancer. On this ED visit, the patient’s vital signs were nor- mal. On examination, she was moaning in pain and clutching her abdomen. The abdomen was tender in both lower quadrants, with guarding but no re- bound. Her sodium level was 125 mEq/L; the day before it had been 132 mEq/L. Urine dipstick testing showed 2+ glucose and 2+ bilirubin; both had been within normal range (negative) the day before. An abdominal/pelvic computed tomography scan with intravenous (IV) and oral contrast did not reveal any potential cause of the patient’s pain. -

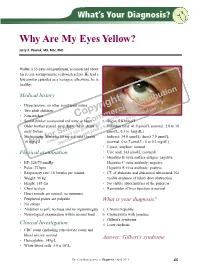

Copyright Why Are My Eyes Yellow?

What’s Your Diagnosis? Why Are My Eyes Yellow? Jerzy K. Pawlak, MD, MSc, PhD Walter, a 55-year-old gentleman, is concerned about his recent asymptomatic yellowish sclera. He had a few similar episodes as a teenager; otherwise, he is healthy. tion Medical history © ibu t tr ad, h is nlo • Hypertension; no other significant issues g D ow ri l n d e • Two adult children y ia ca us p rc ers nal o e us rso • Non-smoker C m ised r pe m hor y fo • Social drinker (occasional red wine or beer) o A• uStugar: 5o.p8 mmol/L C d. le c r ite ing • Older brother passed away due to oheart athtaicbk in a•s Bilirubin total: 41.0 µmol/L (normal: 2.0 to 18 le pro int early forties a use pr µmol/L; 0.1 to 1mg/dL) S ed and • Medications: Moicardis 8o0rmisg q.di.eawnd Crestor Indirect: 34.0 µmol/L; direct 7.0 µmol/L f uth y, v ot na pla 10 mNg q.d. U dis (normal: 0 to 7 µmol/L; 0 to 0.2 mg/dL) • Lipase, amylase: normal Physical examination • Uric acid: 343 µmol/L (normal) • Hepatitis B virus surface antigen: negative • BP: 128/79 mmHg Hepatitis C virus antibody: negative • Pulse: 72 bpm Hepatitis A virus antibody: positive • Respiratory rate: 18 breaths per minute • CT of abdomen and abdominal ultrasound: No • Weight: 90 kg visible evidence of bilary duct obstruction • Height: 185 cm • No visible abnormalities of the pancreas • Chest is clear • Remainder of liver function is normal • Heart sounds are normal, no murmurs • Peripheral pulses are palpable What is your diagnosis? • No edema • Abdomen is soft; no mass and no organomegaly a.