Illuminations Volume 12 | 2011 Illuminations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recipesholdings, & User Guide

LLC 10-SECOND RECIPESHOLDINGS, & USER GUIDE CAPBRAN IMPORTANT SAFEGUARDS • AFTER BLENDING INGREDIENTS, REMOVE THE CROSS BLADE ASSEMBLY—ALLOW THE VESSEL WITH ITS CONTENTS TO SETTLE AND TO RELEASE ANY PRESSURE THAT MAY HAVE BUILT UP DURING THE EXTRACTION PROCESS. IF YOU WILL NOT CONSUME IT IMMEDIATELY, SAVE THESE INSTRUCTIONS USE THE STAY FRESH LID TO CLOSE THE CONTAINER. UNSCREW THE LID AND RELEASE HOUSEHOLD USE ONLY PRESSURE PERIODICALLY IF STORING LONGER THAN A FEW HOURS TO RELEASE ANY ADDED PRESSURE THAT MAY HAVE BUILT UP DUE TO FERMENTATION. Read all instructions before operating the Magic Bullet. When using electrical • NEVER PERMIT ANY BLENDED MIXTURE TO SIT INSIDE A CUP SEALED WITH A CROSS appliances, basic safety precautions should always be followed, including: BLADE BASE WITHOUT FIRST RELEASING THE PRESSURE. • DO NOT ALLOW BLENDED CONTENTS TO SIT FOR LONG PERIODS IN A SEALED GENERAL SAFETY CONTAINER. THE SUGARS IN FRUITS AND VEGETABLES CAN FERMENT, CAUSING PRESSURE TO BUILD UP AND EXPANDLLC IN THE VESSEL WHICH CAN CAUSE INGREDIENTS • Cross blades are sharp. Handle carefully. TO BURST AND SPRAY OUT WHEN MOVED OR OPENED. UNCSCREW THE LID AND OPEN • Always use your Magic Bullet on a clean, flat, hard, dry surface, never on cloth or paper THE CUP FOR A FEW MOMENTS TO RELEASE ANY PRESSURE THAT HAS BUILT UP. which may block the fan vents and cause overheating. • RELEASE PRESSURE BY CAREFULLY UNSCREWING THE LID AND OPENING THE CUP FOR • Do not immerse the cord, plug or base in water or other liquids. A FEW MOMENTS. • Close supervision is necessary when any appliances are used by or near children. -

17 Cut and Run EP- by ECMO (Ozone Records)

19 Nicolette “Ohsay,NaNa” 18 Depth Charge “Depth Charge vs Silver Fox” 17 Cut and Run EP- by ECMO (Ozone records) 16 Badman MDX “Come with me” 15 Orbital “Midnight or choice” 14 Rebel MC “Black meaning good” 13 Nightmares on Wax “A case of Funk” 11 Eon “Fear mind killer” 10 Blapps Posse “Don't hold back” 9 State of Mind “Is that it?” 7 Cookie Watkins “I'm attracted to you” 6 Oceanic “Insanity” 5 Outlander “Vamp” 4 Bugcann “Plastic Jam” 3 Utah Saints “What can you do?” 2 DSK “What would we do?” 1 Prodigy “Charlie says” THE HOUSE THAT JACK BUILT:-____________________________ -Witch Doctor “Sunday afternoon” (Remix) -DCBA “Acid bitch” (Colin Dale dtd 26.08) -Mellow House “The Flower” TONYMONSON;- THE “SWEET RHYTHYMS CHART”:-31.08.1991 25 Reach “Sooner or later” 23 Sable Jeffries “Open your heart” 21 Boyzn'Hood (Force one network) “Spirit” 20 (CD) Le Genre 19 Cheryl Pepsi Riley “Ain't no way” 12 Pride and Politic “Hold on” 11 Phyllis Hyman “Prime of my life” 10 De Bora “Dream about you” 9 Frankie Knuckles “Rain falls” 8 Your's Truly “Come and get it” 7 Mica Parris “Young Soul Rebels” 6 Jean Rice Your'e a victim” (remix) 5 Pinkie “Looking for love” 4 Young Disciples “Talking what I feel” COLIN DALE;- THE “ABSTRACT DANCE SHOW”:-02.09.1991 1 Bizarre,Inc (Brand new) “Raise me” 2 12” on white label from deejay Trance “Let there be house” 3 IE Records - Reel-to-Real “We are EE” 4 Underground Music movement “ Voice of the rave” (from Italy) Electronic- from PTL 5 Exclusive on Acetate 12” from Virtual Reality “Here” 6 12” called Aah - Really hardcore -

Buffy & Angel Watching Order

Start with: End with: BtVS 11 Welcome to the Hellmouth Angel 41 Deep Down BtVS 11 The Harvest Angel 41 Ground State BtVS 11 Witch Angel 41 The House Always Wins BtVS 11 Teacher's Pet Angel 41 Slouching Toward Bethlehem BtVS 12 Never Kill a Boy on the First Date Angel 42 Supersymmetry BtVS 12 The Pack Angel 42 Spin the Bottle BtVS 12 Angel Angel 42 Apocalypse, Nowish BtVS 12 I, Robot... You, Jane Angel 42 Habeas Corpses BtVS 13 The Puppet Show Angel 43 Long Day's Journey BtVS 13 Nightmares Angel 43 Awakening BtVS 13 Out of Mind, Out of Sight Angel 43 Soulless BtVS 13 Prophecy Girl Angel 44 Calvary Angel 44 Salvage BtVS 21 When She Was Bad Angel 44 Release BtVS 21 Some Assembly Required Angel 44 Orpheus BtVS 21 School Hard Angel 45 Players BtVS 21 Inca Mummy Girl Angel 45 Inside Out BtVS 22 Reptile Boy Angel 45 Shiny Happy People BtVS 22 Halloween Angel 45 The Magic Bullet BtVS 22 Lie to Me Angel 46 Sacrifice BtVS 22 The Dark Age Angel 46 Peace Out BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part One Angel 46 Home BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part Two BtVS 23 Ted BtVS 71 Lessons BtVS 23 Bad Eggs BtVS 71 Beneath You BtVS 24 Surprise BtVS 71 Same Time, Same Place BtVS 24 Innocence BtVS 71 Help BtVS 24 Phases BtVS 72 Selfless BtVS 24 Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered BtVS 72 Him BtVS 25 Passion BtVS 72 Conversations with Dead People BtVS 25 Killed by Death BtVS 72 Sleeper BtVS 25 I Only Have Eyes for You BtVS 73 Never Leave Me BtVS 25 Go Fish BtVS 73 Bring on the Night BtVS 26 Becoming, Part One BtVS 73 Showtime BtVS 26 Becoming, Part Two BtVS 74 Potential BtVS 74 -

Electronic Feel Every Beat Mp3, Flac, Wma

Electronic Feel Every Beat mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Pop Album: Feel Every Beat Country: Germany Released: 1991 Style: House, Synth-pop, Hip-House MP3 version RAR size: 1114 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1630 mb WMA version RAR size: 1658 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 675 Other Formats: RA XM WMA ASF AC3 WAV MMF Tracklist Hide Credits Feel Every Beat (7" Remix) 1 3:59 Producer [Additional], Remix – Stephen Hague Feel Every Beat (DNA Mix) 2 5:41 Remix – DNA 3 Second To None 4:03 4 Lean To The Inside 4:06 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Virgin Schallplatten GmbH Copyright (c) – Virgin Schallplatten GmbH Licensed From – Clear Productions Ltd. Licensed To – Virgin Schallplatten GmbH Recorded At – Clear, Manchester Published By – Warner/Chappell Glass Mastered At – DADC Austria Credits Design [Packaged By] – 3a* Engineer – Owen Morris Photography By – Donald Christie Programmed By [Additional] – DNA Written-By, Producer, Guitar, Keyboards, Backing Vocals – Johnny Marr Written-By, Producer, Vocals, Keyboards, Programmed By – Bernard Sumner Notes Recorded at Clear, Manchester. Published by Warner Chappell. Licensed to Virgin Schallplatten GmbH by Clear Productions Ltd. ℗ 1991 Virgin Schallplatten GmbH. © 1991 Virgin Schallplatten GmbH. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode (Text): 5 012980 967162 Barcode: 5012980967162 Matrix / Runout: 664671 11A5 Label Code: LC 3098 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year FAC 328/7 Electronic Feel Every Beat (7", Single) Factory FAC 328/7 -

Song List by Artist

Song List by Artist Artist Song Name 10,000 MANIACS BECAUSE THE NIGHT EAT FOR TWO WHAT'S THE MATTER HERE 10CC RUBBER BULLETS THINGS WE DO FOR LOVE 112 ANYWHERE [FEAT LIL'Z] CUPID PEACHES AND CREAM 112 FEAT SUPER CAT NA NA NA NA 112 FEAT. BEANIE SIGEL,LUDACRIS DANCE WITH ME/PEACHES AND CREAM 12TH MAN MARVELLOUS [FEAT MCG HAMMER] 1927 COMPULSORY HERO 2 BROTHERS ON THE 4TH FLOOR COME TAKE MY HAND NEVER ALONE 2 COW BOYS EVERYBODY GONFI GONE 2 HEADS OUT OF THE CITY 2 LIVE CREW LING ME SO HORNY WIGGLE IT 2 PAC ALL ABOUT U BRENDA’S GOT A BABY Page 1 of 366 Song List by Artist Artist Song Name HEARTZ OF MEN HOW LONG WILL THEY MOURN TO ME? I AIN’T MAD AT CHA PICTURE ME ROLLIN’ TO LIVE & DIE IN L.A. TOSS IT UP TROUBLESOME 96’ 2 UNLIMITED LET THE BEAT CONTROL YOUR BODY LETS GET READY TO RUMBLE REMIX NO LIMIT TRIBAL DANCE 2PAC DO FOR LOVE HOW DO YOU WANT IT KEEP YA HEAD UP OLD SCHOOL SMILE [AND SCARFACE] THUGZ MANSION 3 AMIGOS 25 MILES 2001 3 DOORS DOWN BE LIKE THAT WHEN IM GONE 3 JAYS FEELING IT TOO LOVE CRAZY EXTENDED VOCAL MIX 30 SECONDS TO MARS FROM YESTERDAY 33HZ (HONEY PLEASER/BASS TONE) 38 SPECIAL BACK TO PARADISE BACK WHERE YOU BELONG Page 2 of 366 Song List by Artist Artist Song Name BOYS ARE BACK IN TOWN, THE CAUGHT UP IN YOU HOLD ON LOOSELY IF I'D BEEN THE ONE LIKE NO OTHER NIGHT LOVE DON'T COME EASY SECOND CHANCE TEACHER TEACHER YOU KEEP RUNNIN' AWAY 4 STRINGS TAKE ME AWAY 88 4:00 PM SUKIYAKI 411 DUMB ON MY KNEES [FEAT GHOSTFACE KILLAH] 50 CENT 21 QUESTIONS [FEAT NATE DOGG] A BALTIMORE LOVE THING BUILD YOU UP CANDY SHOP (INSTRUMENTAL) CANDY SHOP (VIDEO) CANDY SHOP [FEAT OLIVIA] GET IN MY CAR GOD GAVE ME STYLE GUNZ COME OUT I DON’T NEED ‘EM I’M SUPPOSED TO DIE TONIGHT IF I CAN’T IN DA CLUB IN MY HOOD JUST A LIL BIT MY TOY SOLDIER ON FIRE Page 3 of 366 Song List by Artist Artist Song Name OUTTA CONTROL PIGGY BANK PLACES TO GO POSITION OF POWER RYDER MUSIC SKI MASK WAY SO AMAZING THIS IS 50 WANKSTA 50 CENT FEAT. -

Mark Summers Sunblock Sunburst Sundance

Key - $ = US Number One (1959-date), ✮ UK Million Seller, ➜ Still in Top 75 at this time. A line in red Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 11 indicates a Number 1, a line in blue indicate a Top 10 hit. SUNFREAKZ Belgian male producer (Tim Janssens) MARK SUMMERS 28 Jul 07 Counting Down The Days (Sunfreakz featuring Andrea Britton) 37 3 British male producer and record label executive. Formerly half of JT Playaz, he also had a hit a Souvlaki and recorded under numerous other pseudonyms Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 3 26 Jan 91 Summers Magic 27 6 SUNKIDS FEATURING CHANCE 15 Feb 97 Inferno (Souvlaki) 24 3 13 Nov 99 Rescue Me 50 2 08 Aug 98 My Time (Souvlaki) 63 1 Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 2 Total Hits : 3 Total Weeks : 10 SUNNY SUNBLOCK 30 Mar 74 Doctor's Orders 7 10 21 Jan 06 I'll Be Ready 4 11 Total Hits : 1 Total Weeks : 10 20 May 06 The First Time (Sunblock featuring Robin Beck) 9 9 28 Apr 07 Baby Baby (Sunblock featuring Sandy) 16 6 SUNSCREEM Total Hits : 3 Total Weeks : 26 29 Feb 92 Pressure 60 2 18 Jul 92 Love U More 23 6 SUNBURST See Matt Darey 17 Oct 92 Perfect Motion 18 5 09 Jan 93 Broken English 13 5 SUNDANCE 27 Mar 93 Pressure US 19 5 08 Nov 97 Sundance 33 2 A remake of "Pressure" 10 Jan 98 Welcome To The Future (Shimmon & Woolfson) 69 1 02 Sep 95 When 47 2 03 Oct 98 Sundance '98 37 2 18 Nov 95 Exodus 40 2 27 Feb 99 The Living Dream 56 1 20 Jan 96 White Skies 25 3 05 Feb 00 Won't Let This Feeling Go 40 2 23 Mar 96 Secrets 36 2 Total Hits : 5 Total Weeks : 8 06 Sep 97 Catch Me (I'm Falling) 55 1 20 Oct 01 Pleaase Save Me (Sunscreem -

NEW DISCOVERY SPORT Ever Since the First Land Rover Vehicle Was Conceived in 1947, We Have Built Vehicles That Challenge What Is Possible

NEW DISCOVERY SPORT Ever since the first Land Rover vehicle was conceived in 1947, we have built vehicles that challenge what is possible. These in turn have challenged their owners to explore new territories and conquer difficult terrains. Our vehicles epitomise the values of the designers and engineers who have created them. Each one instilled with iconic British design cues, delivering capability with composure. Which is how we continue to break new ground, defy conventions and encourage each other to go further. Land Rover truly enables you to make more of your world, to go above and beyond. CONTENTS 06 | INTRODUCTION 08 | DESIGN 16 | VERSATILITY 22 | PERFORMANCE AND CAPABILITY 30 | TECHNOLOGY 46 | SAFETY 50 | SPECIFICATIONS 74 | THE WORLD OF LAND ROVER Vehicle shown is HSE in Byron Blue with optional features fitted (market dependent). Vehicles shown throughout are from the Land Rover global range. Specifications, optional features and their availability may differ by vehicle specification (model and powertrain), or require the installation of other features in order to be fitted. For full feature & option availability please refer to the specification sheet or visit your local Land Rover retailer. INTRODUCTION THE MOST VERSATILE COMPACT LAND ROVER EFFORTLESS LINES, EFFORTLESS DRIVE INTRODUCING NEW DISCOVERY SPORT Our challenge was to make a vehicle that was designed around you and that’s exactly what we did. The beautifully proportioned New Discovery Sport has arrived. Design enabling technologies have been embraced to optimise the front and rear design including LED signature lights, bumpers and grille. These changes have added sophistication to its characterful exterior whilst complementing the engaging nature of the interior design. -

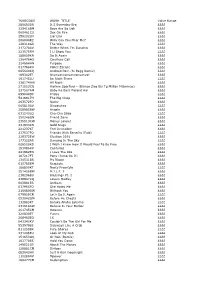

TUNECODE WORK TITLE Value Range 289693DR

TUNECODE WORK_TITLE Value Range 289693DR It S Everyday Bro ££££ 329418BM Boys Are So Ugh ££££ 060461CU Sex On Fire ££££ 258202LN Liar Liar ££££ 2680048Z Willy Can You Hear Me? ££££ 128318GR The Way ££££ 217278AV Better When I'm Dancing ££££ 223575FM I Ll Show You ££££ 188659KN Do It Again ££££ 136476HS Courtesy Call ££££ 224684HN Purpose ££££ 017788KU Police Escape ££££ 065640KQ Android Porn (Si Begg Remix) ££££ 189362ET Nyanyanyanyanyanyanya! ££££ 191745LU Be Right There ££££ 236174HW All Night ££££ 271523CQ Harlem Spartans - (Blanco Zico Bis Tg Millian Mizormac) ££££ 237567AM Baby Ko Bass Pasand Hai ££££ 099044DP Friday ££££ 5416917H The Big Chop ££££ 263572FQ Nasty ££££ 065810AV Dispatches ££££ 258985BW Angels ££££ 031243LQ Cha-Cha Slide ££££ 250248GN Friend Zone ££££ 235513CW Money Longer ££££ 231933KN Gold Slugs ££££ 221237KT Feel Invincible ££££ 237537FQ Friends With Benefits (Fwb) ££££ 228372EW Election 2016 ££££ 177322AR Dancing In The Sky ££££ 006520KS I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel To Be Free ££££ 153086KV Centuries ££££ 241982EN I Love The 90s ££££ 187217FT Pony (Jump On It) ££££ 134531BS My Nigga ££££ 015785EM Regulate ££££ 186800KT Nasty Freestyle ££££ 251426BW M.I.L.F. $ ££££ 238296BU Blessings Pt. 1 ££££ 238847KQ Lovers Medley ££££ 003981ER Anthem ££££ 037965FQ She Hates Me ££££ 216680GW Without You ££££ 079929CR Let's Do It Again ££££ 052042GM Before He Cheats ££££ 132883KT Baraka Allahu Lakuma ££££ 231618AW Believe In Your Barber ££££ 261745CM Ooouuu ££££ 220830ET Funny ££££ 268463EQ 16 ££££ 043343KV Couldn't Be The Girl -

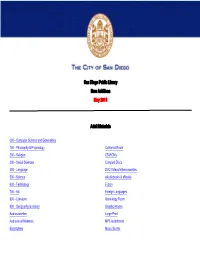

San Diego Public Library New Additions May 2011

San Diego Public Library New Additions May 2011 Adult Materials 000 - Computer Science and Generalities 100 - Philosophy & Psychology California Room 200 - Religion CD-ROMs 300 - Social Sciences Compact Discs 400 - Language DVD Videos/Videocassettes 500 - Science eAudiobooks & eBooks 600 - Technology Fiction 700 - Art Foreign Languages 800 - Literature Genealogy Room 900 - Geography & History Graphic Novels Audiocassettes Large Print Audiovisual Materials MP3 Audiobooks Biographies Music Scores Newspaper Room Fiction Call # Author Title [MYST] FIC/ALEXANDER Alexander, Bruce Murder in Grub Street [MYST] FIC/ANABLE Anable, Stephen A Pinchbeck bride [MYST] FIC/BAUER Bauer, Belinda Darkside [MYST] FIC/BLOCK Block, Lawrence. A drop of the hard stuff : a Matthew Scudder novel [MYST] FIC/BRANDRETH Brandreth, Gyles Daubeney Oscar Wilde and the vampire murders [MYST] FIC/CAMPBELL Campbell‐Slan, Joanna. Photo, snap, shot : a Kiki Lowenstein mystery [MYST] FIC/COLE Cole, Julian. Felicity's gate : a thriller [MYST] FIC/COONTS Coonts, Deborah. Lucky stiff [MYST] FIC/CORLEONE Corleone, Douglas. Night on fire [MYST] FIC/DELANY Delany, Vicki Among the departed [MYST] FIC/DOUDERA Doudera, Vicki A house to die for [MYST] FIC/EDWARDS Edwards, Martin The hanging wood : a Lake District mystery [MYST] FIC/ELKINS Elkins, Aaron J. The worst thing [MYST] FIC/ERICKSON Erickson, K. J. Third person singular [MYST] FIC/FOWLER Fowler, Earlene. Spider web [MYST] FIC/GHELFI Ghelfi, Brent The burning lake : a Volk thriller [MYST] FIC/GOLDENBAUM Goldenbaum, Sally. The wedding shawl [MYST] FIC/GRAVES Graves, Sarah. Knockdown : a home repair is homicide mystery [MYST] FIC/HALL Hall, M. R. The redeemed [MYST] FIC/HAMRICK Hamrick, Janice. Death on tour [MYST] FIC/HARRIS Harris, Charlaine. -

NEW JAGUAR XE a True Jaguar Is Something That Exists to Enjoy and Indulge In, Both Aesthetically and Dynamically

NEW JAGUAR XE A true Jaguar is something that exists to enjoy and indulge in, both aesthetically and dynamically. My inspiration when designing XE was to capture the essence of a very sporty saloon car. It had to have style, attitude, and a presence which differentiates it from any other car in its class. Both technically and visually XE is in perfect balance. IT SAYS INDIVIDUAL, IT SAYS CONFIDENT AND IT SAYS I LOVE TO DRIVE. It's lean, it's sporty, it has a great profile and a fantastic stance. For me, that's XE. IAN CALLUM DIRECTOR OF DESIGN, JAGUAR THE NEW JAGUAR XE SALOON, MEET SPORT To create a four-door saloon which is as fun to drive as a sports car is no mean feat. But the new, redefined XE comfortably meets that criteria. Inspired by F-TYPE – our high-performance car – it's packed with enhancements, innovations and technology. It rewrites the rules of how a compact saloon should behave, and it embodies everything Jaguar is famous for: stylish good looks, precision engineering and a palpable sense of excitement. 06 16 22 38 46 DESIGN PERFORMANCE TECHNOLOGY PRACTICALITY YOUR XE & SAFETY VEHICLES SHOWN ARE FROM THE JAGUAR GLOBAL RANGE. SPECIFICATIONS, OPTIONS AND AVAILABILITY MAY VARY BETWEEN MARKETS AND SHOULD BE VERIFIED WITH YOUR LOCAL JAGUAR RETAILER VEHICLE SHOWN: XE R-DYNAMIC HSE IN CALDERA RED WITH OPTIONAL FEATURES FITTED (MARKET DEPENDENT) DESIGN EVEN STANDING STILL, IT LOOKS FAST Like all Jaguars, XE instinctively manages to catch the eye. From its muscular stance and sculpted bonnet, to the new bumpers, front grille and LED headlights and tail lights, you can tell at a glance that this is one extraordinary sporting saloon. -

![3. SMACK THAT – EMINEM (Feat. Eminem) [Akon:] Shady Convict](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1496/3-smack-that-eminem-feat-eminem-akon-shady-convict-2571496.webp)

3. SMACK THAT – EMINEM (Feat. Eminem) [Akon:] Shady Convict

3. SMACK THAT – EMINEM thing on Get a little drink on (feat. Eminem) They gonna flip for this Akon shit You can bank on it! [Akon:] Pedicure, manicure kitty-cat claws Shady The way she climbs up and down them poles Convict Looking like one of them putty-cat dolls Upfront Trying to hold my woodie back through my Akon draws Slim Shady Steps upstage didn't think I saw Creeps up behind me and she's like "You're!" I see the one, because she be that lady! Hey! I'm like ya I know lets cut to the chase I feel you creeping, I can see it from my No time to waste back to my place shadow Plus from the club to the crib it's like a mile Why don't you pop in my Lamborghini away Gallardo Or more like a palace, shall I say Maybe go to my place and just kick it like Plus I got pal if your gal is game TaeBo In fact he's the one singing the song that's And possibly bend you over look back and playing watch me "Akon!" [Chorus (2X):] [Akon:] Smack that all on the floor I feel you creeping, I can see it from my Smack that give me some more shadow Smack that 'till you get sore Why don't you pop in my Lamborghini Smack that oh-oh! Gallardo Maybe go to my place and just kick it like Upfront style ready to attack now TaeBo Pull in the parking lot slow with the lac down And possibly bend you over look back and Convicts got the whole thing packed now watch me Step in the club now and wardrobe intact now! I feel it down and cracked now (ooh) [Chorus] I see it dull and backed now I'm gonna call her, than I pull the mack down Eminem is rollin', d and em rollin' bo Money -

KEY SONGS and We’Ll Tell Everyone Else

Cover-15.03.13_cover template 12/03/13 09:49 Page 1 11 9 776669 776136 THE BUSINESS OF MUSIC www.musicweek.com 15.03.13 £5.15 40 million albums sold worldwide 8 million albums sold in the UK Project1_Layout 1 12/03/2013 10:07 Page 1 Multiple Grammy Award winner to release sixth studio album ahead of his ten sold out dates in June at the O2 Arena ‘To Be Loved’ 15/04/2013 ‘It’s A Beautiful Day’ 08/04/2013 Radio Added to Heart, Radio 2, Magic, Smooth, Real, BBC Locals Highest New Entry and Highest Mover in Airplay Number 6 in Airplay Chart TV March BBC Breakfast Video Exclusive 25/03 ‘It’s A Beautiful Day’ Video In Rotation 30/03 Ant & Dec Saturday Night Takeaway 12/04 Graham Norton Interview And Performance June 1 Hour ITV Special Expected TV Audience of 16 million, with further TVs to be announced Press Covers and features across the national press Online Over 5.5 million likes on Facebook Over 1 million followers on Twitter Over 250 million views on YouTube Live 10 Consecutive Dates At London’s O2 Arena 30th June • 1st July • 3rd July • 4th July 5thSOLD July OUT • 7thSOLD July OUT • 8thSOLD July OUT • 10thSOLD July OUT 12thSOLD July OUT • 13thSOLD July OUT SOLD OUT SOLD OUT SOLD OUT SOLD OUT Marketing Nationwide Poster Campaign Nationwide TV Advertising Campaign www.michaelbuble.com 01 MARCH15 Cover_v5_cover template 12/03/13 13:51 Page 1 11 9 776669 776136 THE BUSINESS OF MUSIC www.musicweek.com 15.03.13 £5.15 ANALYSIS PROFILE FEATURE 12 15 18 The story of physical and digital Music Week talks to the team How the US genre is entertainment retail in 2012, behind much-loved Sheffield crossing borders ahead of with new figures from ERA venue The Leadmill London’s C2C festival Pet Shop Boys leave Parlophone NEW ALBUM COMING IN JUNE G WORLDWIDE DEAL SIGNED WITH KOBALT LABEL SERVICES TALENT can say they have worked with I BY TIM INGHAM any artist for 28 years, but Parlophone have and we are very et Shop Boys have left proud of that.