The Glacier National Park Visitor Use Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Peaks-Glacier

Glacier National Park Summit List ©2003, 2006 Glacier Mountaineering Society Page 1 Summit El Quadrangle Notes ❑ Adair Ridge 5,366 Camas Ridge West ❑ Ahern Peak 8,749 Ahern Pass ❑ Allen Mountain 9,376 Many Glacier ❑ Almost-A-Dog Mtn. 8,922 Mount Stimson ❑ Altyn Peak 7,947 Many Glacier ❑ Amphitheater Mountain 8,690 Cut Bank Pass ❑ Anaconda Peak 8,279 Mount Geduhn ❑ Angel Wing 7,430 Many Glacier ❑ Apgar Mountains 6,651 McGee Meadow ❑ Apikuni Mountain 9,068 Many Glacier ❑ Appistoki Peak 8,164 Squaw Mountain ❑ B-7 Pillar (3) 8,712 Ahern Pass ❑ Bad Marriage Mtn. 8,350 Cut Bank Pass ❑ Baring Point 7,306 Rising Sun ❑ Barrier Buttes 7,402 Mount Rockwell ❑ Basin Mountain 6,920 Kiowa ❑ Battlement Mountain 8,830 Mount Saint Nicholas ❑ Bear Mountain 8,841 Mount Cleveland ❑ Bear Mountain Point 6,300 Gable Mountain ❑ Bearhat Mountain 8,684 Mount Cannon ❑ Bearhead Mountain 8,406 Squaw Mountain ❑ Belton Hills 6,339 Lake McDonald West ❑ Bighorn Peak 7,185 Vulture Peak ❑ Bishops Cap 9,127 Logan Pass ❑ Bison Mountain 7,833 Squaw Mountain ❑ Blackfoot Mountain 9,574 Mount Jackson ❑ Blacktail Hills 6,092 Blacktail ❑ Boulder Peak 8,528 Mount Carter ❑ Boulder Ridge 6,415 Lake Sherburne ❑ Brave Dog Mountain 8,446 Blacktail ❑ Brown, Mount 8,565 Mount Cannon ❑ Bullhead Point 7,445 Many Glacier ❑ Calf Robe Mountain 7,920 Squaw Mountain ❑ Campbell Mountain 8,245 Porcupine Ridge ❑ Cannon, Mount 8,952 Mount Cannon ❑ Cannon, Mount, SW Pk. 8,716 Mount Cannon ❑ Caper Peak 8,310 Mount Rockwell ❑ Carter, Mount 9,843 Mount Carter ❑ Cataract Mountain 8,180 Logan Pass ❑ Cathedral -

Going-To-The-Sun Road Historic District, Glacier National Park

National Park Service Cultural Landscapes Inventory 2002 Going-to-the-Sun Road Historic District Glacier National Park Table of Contents Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan Concurrence Status Geographic Information and Location Map Management Information National Register Information Chronology & Physical History Analysis & Evaluation of Integrity Condition Treatment Bibliography & Supplemental Information Going-to-the-Sun Road Historic District Glacier National Park Inventory Unit Summary & Site Plan Inventory Summary The Cultural Landscapes Inventory Overview: CLI General Information: Purpose and Goals of the CLI The Cultural Landscapes Inventory (CLI), a comprehensive inventory of all cultural landscapes in the national park system, is one of the most ambitious initiatives of the National Park Service (NPS) Park Cultural Landscapes Program. The CLI is an evaluated inventory of all landscapes having historical significance that are listed on or eligible for listing on the National Register of Historic Places, or are otherwise managed as cultural resources through a public planning process and in which the NPS has or plans to acquire any legal interest. The CLI identifies and documents each landscape’s location, size, physical development, condition, landscape characteristics, character-defining features, as well as other valuable information useful to park management. Cultural landscapes become approved CLIs when concurrence with the findings is obtained from the park superintendent and all required data fields are entered into a national -

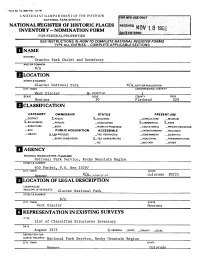

Granite Park Chalet and Dormitory AND/OR COMMON N/A LOCATION

Form No. i0-306 (Rev 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR lli|$|l;!tli:®pls NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES iliiiii: INVENTORY- NOMINATION FORM FOR FEDERAL PROPERTIES SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Granite Park Chalet and Dormitory AND/OR COMMON N/A LOCATION STREET & NUMBER Glacier National Park NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT West Glacier X- VICINITY OF 1 STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Montana 30 Flathead 029 QCLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT X.PUBLIC X_OCCUPIED _ AGRICULTURE —MUSEUM X_BUILDING(S) _PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED X.COMMERCIAL X_RARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT N/AN PR OCESS —YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _ BEING CONSIDERED X-YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY _OTHER: AGENCY REGIONAL HEADQUARTERS: (Happlicable) ______National Park Service, Rocky Mountain Region STREET & NUMBER ____655 Parfet, P.O. Box 25287 CITY. TOWN STATE N/A _____Denver VICINITY OF Colorado 80225 LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS. ETC Qlacier National STREET & NUMBER N/A CITY. TOWN STATE West Glacier Montana REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE List of Classified Structures Inventory DATE August 1975 X-FEDERAL _STATE —COUNTY _LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS National Park Service, Rocky Mountain Region CITY. TOWN STATE Colorado^ DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED —UNALTERED X-ORIGINALSITE X.GOOD —RUINS X-ALTERED —MOVED DATE- _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Granite Park Chalet and Dormitory are situated near the Swiftcurrent Pass in Glacier National Park at an elevation of 7,000 feet. -

Protecting the Crown: a Century of Resource Management in Glacier National Park

Protecting the Crown A Century of Resource Management in Glacier National Park Rocky Mountains Cooperative Ecosystem Studies Unit (RM-CESU) RM-CESU Cooperative Agreement H2380040001 (WASO) RM-CESU Task Agreement J1434080053 Theodore Catton, Principal Investigator University of Montana Department of History Missoula, Montana 59812 Diane Krahe, Researcher University of Montana Department of History Missoula, Montana 59812 Deirdre K. Shaw NPS Key Official and Curator Glacier National Park West Glacier, Montana 59936 June 2011 Table of Contents List of Maps and Photographs v Introduction: Protecting the Crown 1 Chapter 1: A Homeland and a Frontier 5 Chapter 2: A Reservoir of Nature 23 Chapter 3: A Complete Sanctuary 57 Chapter 4: A Vignette of Primitive America 103 Chapter 5: A Sustainable Ecosystem 179 Conclusion: Preserving Different Natures 245 Bibliography 249 Index 261 List of Maps and Photographs MAPS Glacier National Park 22 Threats to Glacier National Park 168 PHOTOGRAPHS Cover - hikers going to Grinnell Glacier, 1930s, HPC 001581 Introduction – Three buses on Going-to-the-Sun Road, 1937, GNPA 11829 1 1.1 Two Cultural Legacies – McDonald family, GNPA 64 5 1.2 Indian Use and Occupancy – unidentified couple by lake, GNPA 24 7 1.3 Scientific Exploration – George B. Grinnell, Web 12 1.4 New Forms of Resource Use – group with stringer of fish, GNPA 551 14 2.1 A Foundation in Law – ranger at check station, GNPA 2874 23 2.2 An Emphasis on Law Enforcement – two park employees on hotel porch, 1915 HPC 001037 25 2.3 Stocking the Park – men with dead mountain lions, GNPA 9199 31 2.4 Balancing Preservation and Use – road-building contractors, 1924, GNPA 304 40 2.5 Forest Protection – Half Moon Fire, 1929, GNPA 11818 45 2.6 Properties on Lake McDonald – cabin in Apgar, Web 54 3.1 A Background of Construction – gas shovel, GTSR, 1937, GNPA 11647 57 3.2 Wildlife Studies in the 1930s – George M. -

GLACIERS and GLACIATION in GLACIER NATIONAL PARK by J Mines Ii

Glaciers and Glacial ion in Glacier National Park Price 25 Cents PUBLISHED BY THE GLACIER NATURAL HISTORY ASSOCIATION IN COOPERATION WITH THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Cover Surveying Sperry Glacier — - Arthur Johnson of U. S. G. S. N. P. S. Photo by J. W. Corson REPRINTED 1962 7.5 M PRINTED IN U. S. A. THE O'NEIL PRINTERS ^i/TsffKpc, KALISPELL, MONTANA GLACIERS AND GLACIATTON In GLACIER NATIONAL PARK By James L. Dyson MT. OBERLIN CIRQUE AND BIRD WOMAN FALLS SPECIAL BULLETIN NO. 2 GLACIER NATURAL HISTORY ASSOCIATION. INC. GLACIERS AND GLACIATION IN GLACIER NATIONAL PARK By J Mines Ii. Dyson Head, Department of Geology and Geography Lafayette College Member, Research Committee on Glaciers American Geophysical Union* The glaciers of Glacier National Park are only a few of many thousands which occur in mountain ranges scattered throughout the world. Glaciers occur in all latitudes and on every continent except Australia. They are present along the Equator on high volcanic peaks of Africa and in the rugged Andes of South America. Even in New Guinea, which many think of as a steaming, tropical jungle island, a few small glaciers occur on the highest mountains. Almost everyone who has made a trip to a high mountain range has heard the term, "snowline," and many persons have used the word with out knowing its real meaning. The true snowline, or "regional snowline" as the geologists call it, is the level above which more snow falls in winter than can he melted or evaporated during the summer. On mountains which rise above the snowline glaciers usually occur. -

Going to the Sun Road Going-To-The-Sun Road Is a Highlight Not to Be Missed During Your Glacier Visit

RV Traveler's Roadmap to Going to the Sun Road Going-to-the-Sun Road is a highlight not to be missed during your Glacier visit. The Road spans 50 miles and crosses the Continental Divide at Logan Pass. During your traverse you will see impressive glaciers, beautiful valleys, cascading waterfalls, towering mountains and colorful wildflowers. 1 Highlights & Facts For The Ideal Experience Going to the Sun Road Glacier Park Trip Length: Roughly 50 miles Best Time To Go: Open from June to mid October What To Watch Out For: Bring sun screen and warm clothing (sweaters, rain gear) Must See Nearby Attractions: Waterton Lakes National Park (contiguous to Glacier, just north of the US-Canada border) A.K.A. Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park 2 Traveler's Notes Trail of the Cedars Due to its popularity, the Going-to-the-Sun Road can be very busy. The parking lot at Logan Pass is usually full between 9:30 and 4:00, which can cause road delays and difficulty finding parking. Not only will you beat traffic with an early start, but animals are often more active earlier in the day to avoid the midday heat. There are no services along the 33 mile stretch of road between Lake McDonald and the Rising Sun Motor Inn. Make sure to bring enough water and snacks for your days’ adventures. A picnic at Logan Pass or one of the scenic turnouts is a great way to enjoy a midday break! While the Going-to-the-Sun Road is very safe and has proper barriers, more timid drivers may want to drive the Going-to-the-Sun Road from East (St. -

Glaciers and Glaciation in Glacier National Park

Glaciers and Glaciation in Glacier National Park ICE CAVE IN THE NOW NON-EXISTENT BOULDER GLACIER PHOTO 1932) Special Bulletin No. 2 GLACIER NATURAL HISTORY ASSOCIATION Price ^fc Cents GLACIERS AND GLACIATION In GLACIER NATIONAL PARK By James L. Dyson MT. OBERLIN CIRQUE AND BIRD WOMAN FALLS SPECIAL BULLETIN NO. 2 GLACIER NATURAL HISTORY ASSOCIATION. INC. In cooperation with NATIONAL PARK SERVICE DEPARTMENT OF INTERIOR PRINTED IN U. S. A. BY GLACIER NATURAL HISTORY ASSOCIATION 1948 Revised 1952 THE O'NEIL PRINTERS- KAUSPELL *rs»JLLAU' GLACIERS AND GLACIATION IN GLACIER NATIONAL PARK By James L. Dyson Head, Department of Geology and Geography Lafayette College Member, Research Committee on Glaciers American Geophysical Union* The glaciers of Glacier National Park are only a few of many thousands which occur in mountain ranges scattered throughout the world. Glaciers occur in all latitudes and on every continent except Australia. They are present along the Equator on high volcanic peaks of Africa and in the rugged Andes of South America. Even in New Guinea, which manj- veterans of World War II know as a steaming, tropical jungle island, a few small glaciers occur on the highest mountains. Almost everyone who has made a trip to a high mountain range has heard the term, "snowline,"' and many persons have used the word with out knowing its real meaning. The true snowline, or "regional snowline"' as the geologists call it, is the level above which more snow falls in winter than can be melted or evaporated during the summer. On mountains which rise above the snowline glaciers usually occur. -

Park Service-Concessioner Relations in Glacier National Park 1892-1961

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1973 Enmity and alliance: Park Service-concessioner relations in Glacier National Park 1892-1961 Michael James Ober The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Ober, Michael James, "Enmity and alliance: Park Service-concessioner relations in Glacier National Park 1892-1961" (1973). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 9204. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/9204 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ENMITY AND ALLIANCE: PARK SERVICE-CONCESSIONER RELATIONS IN GLACIER NATIONAL PARK, 1892-1961 By Michael J. Ober B.A., University of Montana, 1970 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1973 Approved By: Chairman, Board of Examiners De^, Gra^_^e School '9)1^. IX /97 9 Date ' Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: EP40006 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

The Insider's Guide

THE INSIDER’S GUIDE TO: GLACIER NATIONAL PARK, MONTANA There’s a reason Glacier National Park is on practically every Top 10 list involving national parks ever created: this place is amazing. But it’s even more amazing when you experience it as the locals do. Ready to plan your trip with a guide from the inside? Let us help. We are Glacier Guides and Montana Raft, and since 1983, we’ve been your Glacier National Park experts. Glacier Guides and Montana Raft | Glacier Guides Lodge | Glacier Guides Guest House www.glacierguides.com | 406-387-5555 | [email protected] TOP TEN ADVENTURES IN AND AROUND GLACIER NATIONAL PARK #1 HIKING OR BACKPACKING We could never choose just one hike. But with 734 miles of hiking trails, you’re sure to find the trail that suits your group’s abilities and desires. Glacier Guides was chosen by the National Park Service as the exclusive backpacking guide service in Glacier National Park. Join us for a half, whole, or multiple day hiking experience. Scheduled trips leave daily. #2 WHITEWATER RAFTING OR FLOATING The most refreshing way to see Glacier National Park? From the rivers that make up its borders, the North and Middle Forks of the Flathead, a Wild and Scenic River. From lazy floats to intense whitewater rapids, there’s something for kids, grandparents, and adrenaline junkies, too. Call Glacier Guides and Montana Raft to set up your perfect paddling adventure! We rent boats, inflatable kayaks, stand up paddleboards, zayaks, and river gear, too. #3 INTERPRETIVE BOAT TOUR Kids and adults alike will be blown away by the views of Glacier National Park from the middle of one of its beautiful lakes. -

Glacier National Park, 1917

~ ________________ ~'i DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR / FRANKLIN K. LANE. SECRETARY NATIONAL PARK SERVI'CE,/ STEPHEN T. MATHER. DIRECTOR GENERAL ~FO ~N GL CIER NAL ONAL PARK Season of 191 7 The Alps of America-Wonderful Tumbled Region Possessing 60 Glaciers. 250 Lakes, and M y Stately Peaks-Precipices 4,000 Feet Deep-Valleys of Astonish ing Rugged B auty-Scenery Equaling Any in the World- Large, Excellent Hotels and Comfortable Chalet Camps-Good Roads- The Gunsight Trail Across the Top of the Range-Good Trout Fishing-How to Get There-What to See-What to Wear lor MOUiltain Climbing WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1917 TI-IE NATIO .... PARKS AT A GLANCE ( Chron010gIca,l.ly In the order of theIr creatIon [Number,14; Total Area, 7,290 Square Miles] NATIONAL AREA PARKS In DISTINCTIVE CHARACTERISTICS In order of LOCATION square creation miles H ot Springs •..... Middle H 46 hot springs possessing curative properties-Many hotels and 1832 Arkansa.s boording houses-20 bathhouses under public control. CONTENTS. Yellowstone . ••••. North- 3,348 More geysers than in al1 rest of world together-Boiling 1872 western springs-Mud volcanoes-Petrified forests-Grand Canyon Page. Wyoming of the YelIowstone, remarkable for gorgeous coloring-Large General description_ .. _. _. ........ ..... .... ... ... ...... ........ .. 5 lakes-Many large streams and waterfalls-Vast wilderness A romance in rocks . • _. __ . _. _.. .......................... _. ....... 5 inhabited by deer, elk, bison, moose, antelope, bear, moun- The Lewis overthrust .. __. .... _............................... ...... 6 tain sheep, beaver, etc., constituting greatest wild bird and A general view _ . _____ .. ..... ................................. 6 animal preserve in world-Altitude 6,000 to 11,000 feet- The west side .... -

Glacier National Park

COMPLIMENTARY $3.95 2019/2020 YOUR COMPLETE GUIDE TO THE PARKS GLACIER NATIONAL PARK ACTIVITIES • SIGHTSEEING • DINING • LODGING TRAILS • HISTORY • MAPS • MORE OFFICIAL PARTNERS T:5.375” S:4.75” WELCOME S:7.375” On T:8.375” May 11, 1910, Glacier National Park wide variety of activities, animals, trails SO TASTY EVERYONE WILL WANT A BITE. was designated as our nation’s 10th na- and much more. We hope this little green tional park. Known for its glacier-carved guide will become as well-used and well- jagged peaks, turquoise and emerald loved as your hiking boots! lakes, abundant and diverse plant and ani- mal communities and U-shaped valleys, Glacier has become an icon due to its FUN FACTS many designations. In 1932, international cooperation be- Established: Glacier National Park was cre- tween the Rotary Club members of Mon- ated in 1910. Waterton Lakes National tana and Alberta convinced the United Park was first called Waterton Lakes For- States and Canada to join Waterton Lakes est Park when it was created in 1895. and Glacier National Parks as a symbol of their longtime friendship. In recogni- Land Area: Glacier is comprised of 1,600 square tion of this historic agreement, the parks miles. Waterton measures 195 square miles. were designated Waterton-Glacier In- ternational Peace Park, the world’s first Lowest & Highest Elevations: Glacier’s lowest international, transboundary park or pre- elevation is 3,150 feet at the juncture of the serve. In 1995, the Peace Park became Middle and North forks of the Flathead River, while its highest elevation reaches 10,479 the world’s first International Peace feet at the summit of Mount Cleveland. -

Interactions Between Grizzly Bears and Hikers in Glacier National Park, Montana

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Katherine L. McArthur Jope for the degree of Master of Science in Wildlife Science presented on April 26, 1982. Title: Interactions Between Grizzly Bears and Hikers in Glacier National Park, Montana Abstract approved: Redacted for Privacy Edward E. Skey Behavior of grizzly bears (Ursus arctos) toward people was studied by examining hikers' reports of grizzly bear observations and by intensively observing grizzlies in an area of Glacier National Park that was heavily used by day-hikers.Of concern were the appar- ent habituation of grizzly bears to people in the study area, the increasing rate of human injuries by grizzly bears in the park, and the increased involvement of lone adult and subadult bears in inju- ries to hikers. Associations between environmental circumstances, including the presence and behavior of people, and grizzly bears' behavior were evaluated. Human use of the study area was associated primarily with season and weather. Numbers of grizzly bears observed were also associated with season as it reflected patterns of habitat use. Behavior of grizzly bears was associated primarily with the level of human activity, the presence of bear-bells, and the climatic circumstances under which the bears were seen. Although grizzly bears' fear response toward people appeared to habituate, they main- tained a degree of vigilance that was related to conditions affecting the ease of scent perception. Charges, which have been associated with hiker injuries, involved only people who did not have bear- bells. Charges occurred primarily along trails that received little human use although grizzly bears were also startled by hikers on trails with high levels of human use.