Securing Democracy in Cyberspace an Approach to Protecting Data-Driven Elections

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Autorità Per Le Garanzie Nelle Comunicazioni Direzione Contenuti Audiovisivi

Autorità per le Garanzie nelle Comunicazioni Direzione Contenuti Audiovisivi Prot. n. DDA/0001766 del 4 settembre 2017 Comunicazione di avvio del procedimento istruttorio relativo all’istanza DDA/1175, ai sensi del combinato disposto dell’art. 7 del Regolamento allegato alla delibera n. 680/13/CONS e dell’art. 8, comma 3, della legge 7 agosto 1990, n. 241. (Procedimento n. 557/DDA/GDS) Con istanza DDA/1175, pervenuta in data 30 agosto 2017 (prot. n. DDA/0001759), è stata segnalata dalla FPM (Federazione contro la pirateria musicale e multimediale), in qualità di soggetto legittimato giusta delega delle società Sony Music Entertainment Italy Spa, Universal Music Italia Srl, Warner Music Italia Srl, in quanto mandataria per il territorio italiano dei titolari dei diritti di sfruttamento sulle opere oggetto dell’istanza, la presenza di una significativa quantità di opere di carattere sonoro, sul sito internet www.skytorrents.in, in presunta violazione della legge 22 aprile 1941, n. 633, tra cui sono specificamente indicate a titolo esemplificativo e non esaustivo, le seguenti: - “Alessandra Amoroso / Amore puro”, alla pagina internet <omissis>; - “Alessandra Amoroso / Senza nuvole”, alla pagina internet <omissis>; - “Biagio Antonacci / L'amore comporta”, alla pagina internet <omissis>; - “Biagio Antonacci / Inaspettata”, alla pagina internet <omissis>; - “Giorgia / Stonata”, alla pagina internet <omissis>; - “Rocco Hunt / A'verità”, alla pagina internet <omissis>; - “Noemi / Sulla mia pelle”, alla pagina internet <omissis>; - “ Lucio Dalla -

Gfk Italia CERTIFICAZIONI ALBUM Fisici E Digitali Relative Alla Settimana 47 Del 2019 LEGENDA New Award

GfK Italia CERTIFICAZIONI ALBUM fisici e digitali relative alla settimana 47 del 2019 LEGENDA New Award Settimana di Titolo Artista Etichetta Distributore Release Date Certificazione premiazione ZERONOVETOUR PRESENTE RENATO ZERO TATTICA RECORD SERVICE 2009/03/20 DIAMANTE 19/2010 TRACKS 2 VASCO ROSSI CAPITOL UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2009/11/27 DIAMANTE 40/2010 ARRIVEDERCI, MOSTRO! LIGABUE WARNER BROS WMI 2010/05/11 DIAMANTE 42/2010 VIVERE O NIENTE VASCO ROSSI CAPITOL UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2011/03/29 DIAMANTE 19/2011 VIVA I ROMANTICI MODA' ULTRASUONI ARTIST FIRST 2011/02/16 DIAMANTE 32/2011 ORA JOVANOTTI UNIVERSAL UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2011/01/24 DIAMANTE 46/2011 21 ADELE BB (XL REC.) SELF 2011/01/25 8 PLATINO 52/2013 L'AMORE È UNA COSA SEMPLICE TIZIANO FERRO CAPITOL UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2011/11/28 8 PLATINO 52/2013 TZN-THE BEST OF TIZIANO FERRO TIZIANO FERRO CAPITOL UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2014/11/25 8 PLATINO 15/2017 MONDOVISIONE LIGABUE ZOO APERTO WMI 2013/11/26 7 PLATINO 18/2015 LE MIGLIORI MINACELENTANO CLAN CELENTANO SRL - PDU MUSIC SONY MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT 2016/11/11 7 PLATINO 12/2018 INEDITO LAURA PAUSINI ATLANTIC WMI 2011/11/11 6 PLATINO 52/2013 BACKUP 1987-2012 IL BEST JOVANOTTI UNIVERSAL UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2012/11/27 6 PLATINO 18/2015 SONO INNOCENTE VASCO ROSSI CAPITOL UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2014/11/04 6 PLATINO 39/2015 CHRISTMAS MICHAEL BUBLE' WARNER BROS WMI 2011/10/25 6 PLATINO 51/2016 ÷ ED SHEERAN ATLANTIC WMI 2017/03/03 6 PLATINO 44/2019 CHOCABECK ZUCCHERO UNIVERSAL UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2010/10/28 5 PLATINO 52/2013 ALI E RADICI EROS RAMAZZOTTI RCA ITALIANA SONY MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT 2009/05/22 5 PLATINO 52/2013 NOI EROS RAMAZZOTTI UNIVERSAL UNIVERSAL MUSIC 2012/11/13 5 PLATINO 12/2015 LORENZO 2015 CC. -

Your Guide to Over 2500 Channels of Entertainment

YOUR GUIDE TO OVER 2500 CHANNELS OF ENTERTAINMENT Digital Widescreen | July 2017 Journey into the unknown with KONG: SKULL ISLAND and more thrilling movies Voted World’s Best Infl ight Entertainment for the 13th consecutive year! NEW MOVIES | DOCUMENTARIES | SPORT | ARABIC MOVIES | COMEDY TV | KIDS | BOLLYWOOD | DRAMA | NEW MUSIC | BOX SETS | AND MORE OBCOFCJuly17EX2.indd 51 16/06/2017 10:58 EMIRATES ICE_EX2_DIGITAL_WIDESCREEN_57_JULY17 051_FRONT COVER_V1 200X250 44 An extraordinary ENTERTAINMENT experience... Wherever you’re going, whatever your mood, you’ll find over 2500 channels of the world’s best inflight entertainment to explore on today’s flight. THE LATEST Information… Communication… Entertainment… Track the progress of your Stay connected with in-seat* phone, Experience Emirates’ award- MOVIES flight, keep up with news SMS and email, plus Wi-Fi and mobile winning selection of movies, you can’t miss movies and other useful features. roaming on select flights. TV, music and games. from page 16 514 ...AT YOUR FINGERTIPS STAY CONNECTED 4 Connect to the 1500 OnAir Wi-Fi network on all A380s and most Boeing 777s 1 Choose a channel Go straight to your chosen programme by typing the channel 2 3 number into your handset, or use WATCH the onscreen channel entry pad 1 3 LIVE TV Swipe left and Search for Move around Live news and sport right like a tablet. movies, TV using the games channels are available Tap the arrows shows, music controller pad on on most fl ights. Find onscreen to and system your handset out more on page 9. scroll features and select using the green 2 4 Create and Tap Settings to game button 4 access your own adjust volume playlist using and brightness Favourites e Boss Baby Many movies are 102 available in up to eight languages. -

Your Guide to Over 2500 Channels of Entertainment

YOUR GUIDE TO OVER 2500 CHANNELS OF ENTERTAINMENT Voted World’s Best Infl ight Entertainment Digital Widescreen February 2017 for the 12th consecutive year! PLANET Explore the wonders ofEARTH II and more incredible entertainment NEW MOVIES | DOCUMENTARIES | SPORT | ARABIC MOVIES | COMEDY TV | KIDS | BOLLYWOOD | DRAMA | NEW MUSIC | BOX SETS | AND MORE ENTERTAINMENT An extraordinary experience... Wherever you’re going, whatever your mood, you’ll find over 2500 channels of the world’s best inflight entertainment to explore on today’s flight. 496 movies Information… Communication… Entertainment… THE LATEST MOVIES Track the progress of your Stay connected with in-seat* phone, Experience Emirates’ award- flight, keep up with news SMS and email, plus Wi-Fi and mobile winning selection of movies, you can’t miss and other useful features. roaming on select flights. TV, music and games. from page 16 STAY CONNECTED ...AT YOUR FINGERTIPS Connect to the OnAir Wi-Fi 4 103 network on all A380s and most Boeing 777s Move around 1 Choose a channel using the games Go straight to your chosen controller pad programme by typing the on your handset channel number into your and select using 2 3 handset, or use the onscreen the green game channel entry pad button 4 1 3 Swipe left and right like Search for movies, a tablet. Tap the arrows TV shows, music and ĒĬĩĦĦĭ onscreen to scroll system features ÊÉÏ 2 4 Create and access Tap Settings to Português, Español, Deutsch, 日本語, Français, ̷͚͑͘͘͏͐, Polski, 中文, your own playlist adjust volume and using Favourites brightness Many movies are available in up to eight languages. -

PDF Document 364Kb

Autorità per le Garanzie nelle Comunicazioni Direzione Contenuti Audiovisivi Prot. n. DDA/0002169 del 16 settembre 2015 Comunicazione di avvio del procedimento istruttorio relativo all’istanza DDA/491, ai sensi del combinato disposto dell’art. 7 del Regolamento allegato alla delibera n. 680/13/CONS e dell’art. 8, comma 3, della legge 7 agosto 1990, n. 241. (Procedimento n. 207/DDA/AP) Con istanza DDA/491, pervenuta in data 14 settembre 2015 (prot. n. DDA/0002110), è stata stata segnalata dalla FPM - Federazione Contro la Pirateria Musicale e Multimediale, in qualità di soggetto legittimato, giusta delega delle società Sony Music Entertainment Italy S.p.A., Universal Music Italia S.r.l., Warner Music Italia S.r.l., detentrici dei diritti di sfruttamento sulle opere oggetto di istanza, la presenza, sul sito internet http://www.torrentdownload.co, in presunta violazione della legge 22 aprile 1941, n. 633, di una significativa quantità di opere di carattere sonoro, tra le quali sono specificamente indicate, a titolo esemplificativo e non esaustivo, le seguenti: - “Ligabue/Mondovisione”, disponibile alla pagina internet http://www.torrentdownload.co/Ligabue--Mondovisione-+album--2013+- %5BsuperRubens%5D/3CE225CD96A516A20009685AE1BAAC387070CB3A - “Ligabue/Arrivederci mostro”, disponibile alla pagina internet http://www.torrentdownload.co/%28MP3-ITA%29-Luciano-Ligabue--Arrivederci- mostro+-%28CD-RIP%29/23FF8C1FA6CACD7AD8117215363122B6E1E689BD - “Laura Pausini/Inedito”, disponibile alla pagina internet http://www.torrentdownload.co/Laura-Pausini-Inedito-%282011%29-320Kbit%28mp3%29- -

Download PDF File

Jo’ Campana Via E. Tazzoli 3 25128 BRESCIA ITALY C.F. CMPGNN63E30B157J mob +393332461952 mail [email protected] skype jocampana web www.jocampana.com Socio AILD - Associazione Italiana Lighting Designers www.aild.it 1987 Vasco Rossi ’Cè chi dice no’ tour tecnico audio Deacon Blue Italian tour tecnico audio Milano Suono Festival tecnico audio (C.Hisaac, Del Fuegos, In Tua Nua, New Model Army, The Wailers, Level 42, Marillon, P.Weller, C.Rea, G.Moore, T.Headon) 1988 PFM tour invernale tecnico audio Milano Suono Festival tecnico audio ( Jethro Tull, All Jarreau, George Benson, D.Sanborn, Tuxedomoon ) Milva ‘Canzoni tra le due guerre’ tour teatrale tecnico luci Gino Paoli ‘L’ufficio delle cose perdute’ tour teatrale tecnico luci Salomon Burke live in Reggio Emilia tecnico luci Moda a Trinità dei Monti Roma ‘Donna sotto le stelle’ tecnico luci 1989 Vasco Rossi ‘Liberi Liberi’ tour tecnico luci Joe Zawinul live in Sassabanek tecnico luci Miriam Makeba live in Milano, P.zza Duomo tecnico luci Jazz Varese Festival (Herbie Hancock, Mike Stern) tecnico luci Moda a Trinità dei Monti Roma ‘Donna sotto le stelle’ tecnico luci 1990 Vasco Rossi ‘Fronte del Palco’ live in Milano e Roma tecnico luci Anna Oxa Summer tour tecnico luci Eros Ramazzotti ‘In Ogni Senso’ European tour tecnico luci/rigger Barry White Italian tour tecnico luci Festival Villa Arconati Varese dimmerista/tecnico luci (Al Di Meola, Joao Gilberto, John Lurie) Premio Tenco Teatro Ariston S.Remo tecnico luci Moda a Trinità dei Monti Roma ‘Donna sotto le stelle’ tecnico luci 1991 Vasco -

Billboard Magazine

Pop's princess takes country's newbie under her wing as part of this season's live music mash -up, May 31, 2014 1billboard.com a girl -powered punch completewith talk of, yep, who gets to wear the transparent skirt So 99U 8.99C,, UK £5.50 SAMSUNG THE NEXT BIG THING IN MUSIC 200+ Ad Free* Customized MINI I LK Stations Radio For You Powered by: Q SLACKER With more than 200 stations and a catalog of over 13 million songs, listen to your favorite songs with no interruption from ads. GET IT ON 0)*.Google play *For a limited time 2014 Samsung Telecommunications America, LLC. Samsung and Milk Music are both trademarks of Samsung Electronics Co. Ltd. Appearance of device may vary. Device screen imagessimulated. Other company names, product names and marks mentioned herein are the property of their respective owners and may be trademarks or registered trademarks. Contents ON THE COVER Katy Perry and Kacey Musgraves photographed by Lauren Dukoff on April 17 at Sony Pictures in Culver City. For an exclusive interview and behind-the-scenes video, go to Billboard.com or Billboard.com/ipad. THIS WEEK Special Double Issue Volume 126 / No. 18 TO OUR READERS Billboard will publish its next issue on June 7. Please check Billboard.biz for 24-7 business coverage. Kesha photographed by Austin Hargrave on May 18 at the MGM Grand Garden Arena in Las Vegas. FEATURES TOPLINE MUSIC 30 Kacey Musgraves and Katy 5 Can anything stop the rise of 47 Robyn and Royksopp, Perry What’s expected when Spotify? (Yes, actually.) Christina Perri, Deniro Farrar 16 a country ingenue and a Chart Movers Latin’s 50 Reviews Coldplay, pop superstar meet up on pop trouble, Disclosure John Fullbright, Quirke 40 “ getting ready for tour? Fun and profits. -

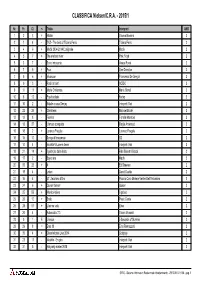

CLASSIFICA Nielsen/C.R.A. - 2015/1

CLASSIFICA Nielsen/C.R.A. - 2015/1 Nr. Pr. Cl. +- Titolo Interpreti AMD 1 2 3 + Hitalia Gianna Nannini 2 2 1 4 - TNZ - The best of Tiziano Ferro Tiziano Ferro 2 3 4 6 + Modà 2004-2014 L'originale Modà 2 4 5 7 + The endless river Pink Floyd 2 5 3 7 - Sono innocente Vasco Rossi 2 6 7 5 + Four One Direction 2 7 9 6 + Vivavoce Francesco De Gregori 2 8 6 3 - Rock or bust AC/DC 2 9 11 11 + Mario Christmas Mario Biondi 2 10 8 12 - Pop-hoolista Fedez 2 11 10 2 - Natale a casa Deejay Interpreti Vari 2 12 22 29 + Christmas Michael Bublé 2 13 12 8 - Fiorella Fiorella Mannoia 2 14 13 37 - L'amore comporta Biagio Antonacci 2 15 18 2 + Lorenzo Fragola Lorenzo Fragola 2 16 15 10 - Songs of innocence U2 2 17 14 4 - Violetta V-Lovers 4ever Interpreti Vari 2 18 21 14 + Il padrone della festa Fabi Silvestri Gazzè 2 19 17 2 - Sayonara Madh 2 20 33 26 + X Ed Sheeran 2 21 19 4 - Listen David Guetta 2 22 16 4 - 57° Zecchino d'Oro Piccolo Coro Mariele Ventre Dell'Antoniano 2 23 24 6 + Queen forever Queen 2 24 25 56 + Mondovisione Ligabue 2 25 26 10 + Snob Paolo Conte 2 26 28 57 + L'anima vola Elisa 2 27 20 4 - Autoscatto 7.0 Gianni Morandi 2 28 0 1 E Livesos 5 Seconds of Summer 2 29 29 8 = Eros 30 Eros Ramazzotti 2 30 35 4 + Ghost stories Live 2014 Coldplay 2 31 23 11 - Violetta - En gira Interpreti Vari 2 32 31 5 - Hot party winter 2015 Interpreti Vari 2 SIRIO - Sistema Informativo Redazionale Intrattenimento - 29/12/2014 18:04 - pag. -

Citiesthatrock 6Dic Finale

Dolci violini, calde chitarre acustiche o potenti bassi ritmati? Amazon svela i gusti musicali delle città italiane: Asti “capitale del pop”, Cremona la “metallara”, Siena l'”indie” • 57 città italiane e 6 generi musicali: le top ten di chi ascolta più musica pop, classica, jazz, heavy metal, alternativa e rock • Gli album più venduti per genere musicale: dagli idoli del momento One Direction, all'eleganza avvolgente di Miles Davis, dal rock graffiante dei Guns N’ Roses ai ricercati Sigur Ròs • I CD più acquistati di sempre su Amazon.it: cantautori italiani in testa con Ligabue e Jovanotti • Le sonorità d'avanguardia dei Daft Punk sposano il sound vintage del vinile: il loro “Random Access Memory” il vinile più venduto su Amazon.it Lussemburgo, 6 dicembre 2013 – Se d'ora in avanti passeggiando per le strade di Asti sentirete musica pop, mentre a Busto Arsizio sarete rapiti da vivaci arie classiche non stupitevi: per la prima volta in Italia, Amazon svela infatti i gusti musicali preferiti delle 57 città più popolose, rivelando anche gli album più acquistati per genere, vale a dire pop, classica, jazz, heavy metal, indie e rock. Sebbene, guardando alle vendite assolute del negozio Musica su Amazon.it a partire dalla sua apertura1 l'Italia si dimostri patriotticamente unita attorno a cantautori nostrani come Ligabue e il suo “Mondovisione”, Jovanotti con il cofanetto “Backup - Lorenzo 1987-2012” e Francesco Guccini con “L’Ultima Thule”, rispettivamente nelle prime 3 posizioni, in fatto di specifici gusti musicali ciascuna città dimostra -

PDF Document 350Kb

Autorità per le Garanzie nelle Comunicazioni Direzione Contenuti Audiovisivi Prot. n. DDA/0001239 del 18 giugno 2018 Comunicazione di avvio del procedimento istruttorio relativo all’istanza DDA/1494, ai sensi del combinato disposto dell’art. 7 del Regolamento allegato alla delibera n. 680/13/CONS e dell’art. 8, comma 3, della legge 7 agosto 1990, n. 241. (Procedimento n. 787/DDA/EL) Con istanza DDA/1494, pervenuta in data 14 giugno 2018 (prot. n. DDA/0001173), è stata segnalata dalla FPM (Federazione contro la pirateria musicale e multimediale), in qualità di soggetto legittimato, in quanto delegata dai titolari dei diritti di sfruttamento sulle opere oggetto dell’istanza Sony Music Entertainment Italy S.p.a. e Universal Music Italy s.r.l., la presenza di una significativa quantità di opere di carattere sonoro, sul sito internet http://bitmp3.ru/, in presunta violazione della legge 22 aprile 1941, n. 633, tra cui sono specificamente indicate a titolo esemplificativo e non esaustivo, le seguenti: - Gianna Nannini | Io e te - Giorgia | Dietro le apparenze - Marco Mengoni | Pronto a correre - Fedez | Il mio primo disco da venduto - Alessandra Amoroso | Senza nuvole - Biagio Antonacci | L'amore comporta - Gianna Nannini | Inno - Noemi | Sulla mia pelle - Biagio Antonacci | Inaspettata - Alessandra Amoroso | Il mondo in un secondo - Alessandra Amoroso | Amore puro - Giorgia | Stonata - Fedez | Signor Brainwash - L'arte di accontentare - Lucio Dalla | Viaggi organizzati - Vasco Rossi | Gli spari sopra - Jovanotti | Safari - Jovanotti | Una -

PDF Document 336Kb

Autorità per le Garanzie nelle Comunicazioni Direzione Servizi Media Prot. n. DDA/0000029 del 18 aprile 2014 Comunicazione di avvio del procedimento istruttorio relativo all’istanza DDA/32 ai sensi del combinato disposto dell’articolo 7 del Regolamento allegato alla delibera n. 680/13/CONS e dell’articolo 8, comma 3, della legge 7 agosto 1990, n. 241. (Procedimento n. 06/DDA/AC) Con istanza DDA/32, pervenuta in data 16 aprile 2014 (prot. n. DDA/0000023), è stata segnalata dalla FPM (Federazione contro la Pirateria Musicale e Multimediale) in qualità di soggetto legittimato, giusta delega delle società Sony Music Entertainment Italy S.p.A, Warner Music Italia S.r.l. e Universal Music Italia S.r.l., detentrici dei diritti di sfruttamento per il territorio italiano sulle opere oggetto di istanza, la presenza, sul sito torrentdownload.ws, in presunta violazione della legge 22 aprile 1941, n. 633, di una significativa quantità di opere di carattere sonoro (alla data della presentazione dell’istanza pari a n. 300.950), molte delle quali il soggetto istante FPM dichiara essere di titolarità dei propri associati, tra cui sono specificamente indicate, a titolo esemplificativo e non esaustivo, le seguenti: - “Ligabue/Mondovisione”, all’URL http://www.torrentdownload.ws/Ligabue--Mondovisione-+album--2013+- %5BsuperRubens%5D/3CE225CD96A516A20009685AE1BAAC387070CB3A - “Ligabue/Arrivederci mostro” all’URL http://www.torrentdownload.ws/%28MP3-ITA%29-Luciano-Ligabue-- Arrivederci-mostro+-%28CD-RIP%29/23F F8C1FA6CACD7AD8117215363122B6E1E689BD; - “Laura -

Sanremo, Da Tenco a Fiorella

mercoledì 8 febbraio 2017 Culture e società 17 Sogno o son Festival/Rai e Mediaset sullo stesso palco: è partita la kermesse Conti-De Filippi Sanremo, da Tenco a Fiorella Nella notte dei presentatori, reri e Fabrizio Moro (nel decennale del - musicalmente così così, la sua “Pensa”) fa altrettanto, con un Tiziano Ferro commemora, quattro-accordi-quattro dal minimo sforzo. Elodie, dai capelli Hello Kitty, Ron scalda il cuore, canta Emma (“È tutta colpa mia” porta e la Mannoia incanta la firma della Marrone, e il testo crea imbarazzo). Lodovica Comello e Ales - di Beppe Donadio sio Bernabei stonacchiano, mentre Sa - muel (Subsonica) porta del ritmo, sen - “Cari amici vicini e lontani, buonasera za aggiungere troppa carne al fuoco. ovunque voi siate”. Si chiamava Nunzio Così il grande vecchio Al Bano, alla fine, Filogamo ed è stato il primo presenta - si mangia a colazione tutti quanti con tore del Festival, quando Sanremo era una romanza firmata Maurizio Fabri - radiofonico e non in Mondovisione. zio (autore de “I migliori anni della no - Sono trascorsi 67 anni e la gara canora stra vita” e di molti buoni spartiti di – superata una crisi di metà anni Set - canzone italiana). Canta anche la cop - tanta – non perde un colpo. Calcistica - pia Cortellesi-Albanese, in un duetto mente parlando, tre Sanremo di fila sentimental-amoroso strampalato, ac - sono riusciti solo a Claudio Cecchetto. cozzaglia ordinata dei più noti “ti amo” Inarrivabili e plurimedagliati Mike della kermesse (è promozione cinema - Bongiorno, ininterrottamente dal 1963 tografica). Ron, quando non ti aspetti al ’67, e Pippo Baudo, padrone assoluto più nulla, piazza un colpo di tutto ri - dal ’92 al ’96.