The First Complete Edition of the Lieder by Louis Spohr. Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

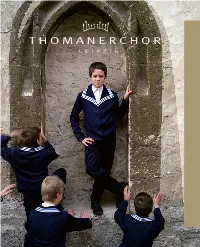

T H O M a N E R C H

Thomanerchor LeIPZIG DerThomaner chor Der Thomaner chor ts n te on C F o able T Ta b l e o f c o n T e n T s Greeting from “Thomaskantor” Biller (Cantor of the St Thomas Boys Choir) ......................... 04 The “Thomanerchor Leipzig” St Thomas Boys Choir Now Performing: The Thomanerchor Leipzig ............................................................................. 06 Musical Presence in Historical Places ........................................................................................ 07 The Thomaner: Choir and School, a Tradition of Unity for 800 Years .......................................... 08 The Alumnat – a World of Its Own .............................................................................................. 09 “Keyboard Polisher”, or Responsibility in Detail ........................................................................ 10 “Once a Thomaner, always a Thomaner” ................................................................................... 11 Soli Deo Gloria .......................................................................................................................... 12 Everyday Life in the Choir: Singing Is “Only” a Part ................................................................... 13 A Brief History of the St Thomas Boys Choir ............................................................................... 14 Leisure Time Always on the Move .................................................................................................................. 16 ... By the Way -

My Musical Lineage Since the 1600S

Paris Smaragdis My musical lineage Richard Boulanger since the 1600s Barry Vercoe Names in bold are people you should recognize from music history class if you were not asleep. Malcolm Peyton Hugo Norden Joji Yuasa Alan Black Bernard Rands Jack Jarrett Roger Reynolds Irving Fine Edward Cone Edward Steuerman Wolfgang Fortner Felix Winternitz Sebastian Matthews Howard Thatcher Hugo Kontschak Michael Czajkowski Pierre Boulez Luciano Berio Bruno Maderna Boris Blacher Erich Peter Tibor Kozma Bernhard Heiden Aaron Copland Walter Piston Ross Lee Finney Jr Leo Sowerby Bernard Wagenaar René Leibowitz Vincent Persichetti Andrée Vaurabourg Olivier Messiaen Giulio Cesare Paribeni Giorgio Federico Ghedini Luigi Dallapiccola Hermann Scherchen Alessandro Bustini Antonio Guarnieri Gian Francesco Malipiero Friedrich Ernst Koch Paul Hindemith Sergei Koussevitzky Circa 20th century Leopold Wolfsohn Rubin Goldmark Archibald Davinson Clifford Heilman Edward Ballantine George Enescu Harris Shaw Edward Burlingame Hill Roger Sessions Nadia Boulanger Johan Wagenaar Maurice Ravel Anton Webern Paul Dukas Alban Berg Fritz Reiner Darius Milhaud Olga Samaroff Marcel Dupré Ernesto Consolo Vito Frazzi Marco Enrico Bossi Antonio Smareglia Arnold Mendelssohn Bernhard Sekles Maurice Emmanuel Antonín Dvořák Arthur Nikisch Robert Fuchs Sigismond Bachrich Jules Massenet Margaret Ruthven Lang Frederick Field Bullard George Elbridge Whiting Horatio Parker Ernest Bloch Raissa Myshetskaya Paul Vidal Gabriel Fauré André Gédalge Arnold Schoenberg Théodore Dubois Béla Bartók Vincent -

THE VIRTUOSO UNDER SUBJECTION: HOW GERMAN IDEALISM SHAPED the CRITICAL RECEPTION of INSTRUMENTAL VIRTUOSITY in EUROPE, C. 1815 A

THE VIRTUOSO UNDER SUBJECTION: HOW GERMAN IDEALISM SHAPED THE CRITICAL RECEPTION OF INSTRUMENTAL VIRTUOSITY IN EUROPE, c. 1815–1850 A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Zarko Cvejic August 2011 © 2011 Zarko Cvejic THE VIRTUOSO UNDER SUBJECTION: HOW GERMAN IDEALISM SHAPED THE CRITICAL RECEPTION OF INSTRUMENTAL VIRTUOSITY IN EUROPE, c. 1815–1850 Zarko Cvejic, Ph. D. Cornell University 2011 The purpose of this dissertation is to offer a novel reading of the steady decline that instrumental virtuosity underwent in its critical reception between c. 1815 and c. 1850, represented here by a selection of the most influential music periodicals edited in Europe at that time. In contemporary philosophy, the same period saw, on the one hand, the reconceptualization of music (especially of instrumental music) from ―pleasant nonsense‖ (Sulzer) and a merely ―agreeable art‖ (Kant) into the ―most romantic of the arts‖ (E. T. A. Hoffmann), a radically disembodied, aesthetically autonomous, and transcendent art and on the other, the growing suspicion about the tenability of the free subject of the Enlightenment. This dissertation‘s main claim is that those three developments did not merely coincide but, rather, that the changes in the aesthetics of music and the philosophy of subjectivity around 1800 made a deep impact on the contemporary critical reception of instrumental virtuosity. More precisely, it seems that instrumental virtuosity was increasingly regarded with suspicion because it was deemed incompatible with, and even threatening to, the new philosophic conception of music and via it, to the increasingly beleaguered notion of subjective freedom that music thus reconceived was meant to symbolize. -

![[STENDHAL]. — Joachim Rossini , Von MARIA OTTINGUER, Leipzig 1852](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2533/stendhal-joachim-rossini-von-maria-ottinguer-leipzig-1852-472533.webp)

[STENDHAL]. — Joachim Rossini , Von MARIA OTTINGUER, Leipzig 1852

REVUE DES DEUX MONDES , 15th May 1854, pp. 731-757. Vie de Rossini , par M. BEYLE [STENDHAL]. — Joachim Rossini , von MARIA OTTINGUER, Leipzig 1852. SECONDE PÉRIODE ITALIENNE. — D’OTELLO A SEMIRAMIDE. IV. — CENERENTOLA ET CENDRILLON. — UN PAMPHLET DE WEBER. — LA GAZZA LADRA. — MOSÈ [MOSÈ IN EGITTO]. On sait que Rossini avait exigé cinq cents ducats pour prix de la partition d’Otello (1). Quel ne fut point l’étonnement du maestro lorsque le lendemain de la première représentation de son ouvrage il reçut du secrétaire de Barbaja [Barbaia] une lettre qui l’avisait qu’on venait de mettre à sa disposition le double de cette somme! Rossini courut aussitôt chez la Colbrand [Colbran], qui, pour première preuve de son amour, lui demanda ce jour-là de quitter Naples à l’instant même. — Barbaja [Barbaia] nous observe, ajouta-t-elle, et commence à s’apercevoir que vous m’êtes moins indifférent que je ne voudrais le lui faire croire ; les mauvaises langues chuchotent : il est donc grand temps de détourner les soupçons et de nous séparer. Rossini prit la chose en philosophe, et se rappelant à cette occasion que le directeur du théâtre Valle le tourmentait pour avoir un opéra, il partit pour Rome, où d’ailleurs il ne fit cette fois qu’une rapide apparition. Composer la Cenerentola fut pour lui l’affaire de dix-huit jours, et le public romain, qui d’abord avait montré de l’hésitation à l’endroit de la musique du Barbier [Il Barbiere di Siviglia ], goûta sans réserve, dès la première épreuve, cet opéra, d’une gaieté plus vivante, plus // 732 // ronde, plus communicative, mais aussi trop dépourvue de cet idéal que Cimarosa mêle à ses plus franches bouffonneries. -

Orchestral Conducting in the Nineteenth Century," Edited by Roberto Illiano and Michela Niccolai Clive Brown University of Leeds

Performance Practice Review Volume 21 | Number 1 Article 2 "Orchestral Conducting in the Nineteenth Century," edited by Roberto Illiano and Michela Niccolai Clive Brown University of Leeds Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr Part of the Music Performance Commons, and the Other Music Commons Brown, Clive (2016) ""Orchestral Conducting in the Nineteenth Century," edited by Roberto Illiano and Michela Niccolai," Performance Practice Review: Vol. 21: No. 1, Article 2. DOI: 10.5642/perfpr.201621.01.02 Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/ppr/vol21/iss1/2 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Claremont at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Performance Practice Review by an authorized editor of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Book review: Illiano, R., M. Niccolai, eds. Orchestral Conducting in the Nineteenth Century. Turnhout: Brepols, 2014. ISBN: 9782503552477. Clive Brown Although the title of this book may suggest a comprehensive study of nineteenth- century conducting, it in fact contains a collection of eighteen essays by different au- thors, offering a series of highlights rather than a broad and connected picture. The collection arises from an international conference in La Spezia, Italy in 2011, one of a series of enterprising and stimulating annual conferences focusing on aspects of nineteenth-century music that has been supported by the Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini (Lucca), in this case in collaboration with the Società di Concerti della Spezia and the Palazzetto Bru Zane Centre de musique romantique française (Venice). -

Moritz Hauptmann War Als Geiger, Komponist, Musik- Theoretiker Und Musikschriftsteller Sehr Geachtet Und Ein Hoch Frequentierter Lehrer

Hauptmann, Moritz Profil Moritz Hauptmann war als Geiger, Komponist, Musik- theoretiker und Musikschriftsteller sehr geachtet und ein hoch frequentierter Lehrer. Sowohl als Privatlehrer als auch ab 1843 im Rahmen seiner Lehrtätigkeit am Leipzi- ger Konservatorium bildete er zahlreiche Musikerinnen und Musiker aus. Sein polarisiertes Geschlechterbild ist auch in dieser Hinsicht von besonderer Bedeutung. Orte und Länder Moritz Hauptmann wurde 1792 in Dresden geboren und ging nach kurzen Aufenthalten in Gotha und Wien als Hauslehrer nach Russland. 1822 wurde er Geiger in der kurfürstlichen Kapelle in Kassel. Von dort wurde er 1842 nach Leipzig berufen, wo er bis zu seinem Tod 1868 als Thomaskantor, Kompositionslehrer, Musiktheoretiker und Musikschriftsteller wirkte. Biografie Moritz Hauptmann wurde 1792 in Dresden als Sohn des Architekten und Akademieprofessors Johann Gottlieb Hauptmann geboren. Schon früh erlernte er Geige, Kla- vier, Musiktheorie und Komposition und wurde 1811 Moritz Hauptmann. Gemälde von seiner Frau Susette Schüler von Ludwig Spohr in Gotha. Es folgte die Anstel- Hauptmann. lung als Geiger in der Hofkapelle in Dresden, anschlie- ßend im Theaterorchester Wien. 1915 wurde er Hausmu- Moritz Hauptmann siklehrer des Fürsten Repnin in Petersburg, Moskau, Pol- tawa und Odessa. Von 1822 bis 1842 war er Mitglied der * 13. Oktober 1792 in Dresden, Deutschland von Spohr geleiteten kurfürstlichen Kapelle in Kassel. † 3. Januar 1868 in Leipzig, Deutschland Auf Empfehlung Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdys und Spohrs erhielt er 1842 die -

Carl Loewe's "Gregor Auf Dem Stein": a Precursor to Late German Romanticism

Carl Loewe's "Gregor auf dem Stein": A Precursor to Late German Romanticism Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Witkowski, Brian Charles Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 04/10/2021 03:11:55 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/217070 CARL LOEWE'S “GREGOR AUF DEM STEIN”: A PRECURSOR TO LATE GERMAN ROMANTICISM by Brian Charles Witkowski _____________________ Copyright © Brian Charles Witkowski 2011 A Document Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2011 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Document Committee, we certify that we have read the document prepared by Brian Charles Witkowski entitled Carl Loewe's “Gregor auf dem Stein”: A Precursor to Late German Romanticism and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts ________________________________________________ Date: 11/14/11 Charles Roe ________________________________________________ Date: 11/14/11 Faye Robinson ________________________________________________ Date: 11/14/11 Kristin Dauphinais Final approval and acceptance of this document is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the document to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this document prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the document requirement. -

Classic Choices April 6 - 12

CLASSIC CHOICES APRIL 6 - 12 PLAY DATE : Sun, 04/12/2020 6:07 AM Antonio Vivaldi Violin Concerto No. 3 6:15 AM Georg Christoph Wagenseil Concerto for Harp, Two Violins and Cello 6:31 AM Guillaume de Machaut De toutes flours (Of all flowers) 6:39 AM Jean-Philippe Rameau Gavotte and 6 Doubles 6:47 AM Ludwig Van Beethoven Consecration of the House Overture 7:07 AM Louis-Nicolas Clerambault Trio Sonata 7:18 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Divertimento for Winds 7:31 AM John Hebden Concerto No. 2 7:40 AM Jan Vaclav Vorisek Sonata quasi una fantasia 8:07 AM Alessandro Marcello Oboe Concerto 8:19 AM Franz Joseph Haydn Symphony No. 70 8:38 AM Darius Milhaud Carnaval D'Aix Op 83b 9:11 AM Richard Strauss Der Rosenkavalier: Concert Suite 9:34 AM Max Reger Flute Serenade 9:55 AM Harold Arlen Last Night When We Were Young 10:08 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Exsultate, Jubilate (Motet) 10:25 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony No. 3 10:35 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Piano Concerto No. 10 (for two pianos) 11:02 AM Johannes Brahms Symphony No. 4 11:47 AM William Lawes Fantasia Suite No. 2 12:08 PM John Ireland Rhapsody 12:17 PM Heitor Villa-Lobos Amazonas (Symphonic Poem) 12:30 PM Allen Vizzutti Celebration 12:41 PM Johann Strauss, Jr. Traumbild I, symphonic poem 12:55 PM Nino Rota Romeo & Juliet and La Strada Love 12:59 PM Max Bruch Symphony No. 1 1:29 PM Pr. Louis Ferdinand of Prussia Octet 2:08 PM Muzio Clementi Symphony No. -

German Virtuosity

CONCERT PROGRAM III: German Virtuosity July 20 and 22 PROGRAM OVERVIEW Concert Program III continues the festival’s journey from the Classical period Thursday, July 20 into the nineteenth century. The program offers Beethoven’s final violin 7:30 p.m., Stent Family Hall, Menlo School sonata as its point of departure into the new era—following a nod to the French Saturday, July 22 virtuoso Pierre Rode, another of Viotti’s disciples and the sonata’s dedicatee. In 6:00 p.m., The Center for Performing Arts at Menlo-Atherton the generation following Beethoven, Louis Spohr would become a standard- bearer for the German violin tradition, introducing expressive innovations SPECIAL THANKS such as those heard in his Double String Quartet that gave Romanticism its Music@Menlo dedicates these performances to the following individuals and musical soul. The program continues with music by Ferdinand David, Spohr’s organizations with gratitude for their generous support: prize pupil and muse to the German tradition’s most brilliant medium, Felix July 20: The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation Mendelssohn, whose Opus 3 Piano Quartet closes the program. July 22: Alan and Corinne Barkin PIERRE RODE (1774–1830) FERDINAND DAVID (1810–1873) Caprice no. 3 in G Major from Vingt-quatre caprices en forme d’études for Solo Caprice in c minor from Six Caprices for Solo Violin, op. 9, no. 3 (1839) CONCERT PROGRAMS CONCERT Violin (ca. 1815) Sean Lee, violin Arnaud Sussmann, violin FELIX MENDELSSOHN (1809–1847) LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN (1770–1827) Piano Quartet no. 3 in b minor, op. 3 (1825) Violin Sonata no. -

Section 2 Stage Works Operas Ballets Teil 2 Bühnenwerke

SECTION 2 STAGE WORKS OPERAS BALLETS TEIL 2 BÜHNENWERKE BALLETTE 267 268 Bergh d’Albert, Eugen (1864–1932) Amram, David (b. 1930) Mister Wu The Final Ingredient Oper in drei Akten. Text von M. Karlev nach dem gleichnamigen Drama Opera in One Act, adapted from the play by Reginald Rose. Libretto by von Harry M. Vernon und Harald Owen. (Deutsch) Arnold Weinstein. (English) Opera in Three Acts. Text by M. Karlev based on the play of the same 12 Solo Voices—SATB Chorus—2.2.2.2—4.2.3.0—Timp—2Perc—Str / name by Harry M. Vernon and Harald Owen. (German) 57' Voices—3.3(III=Ca).2(II=ClEb).B-cl(Cl).3—4.3.3.1—Timp—Perc— C F Peters Corporation Hp/Cel—Str—Off-stage: 1.0.Ca.0.1—0.0.0.0—Perc(Tamb)—2Gtr—Vc / 150' Twelfth Night Heinrichshofen Opera. Text adapted from Shakespeare’s play by Joseph Papp. (English) _________________________________________________________ 13 Solo Voices—SATB Chorus—1.1.1.1—2.1.1.0—Timp—2Perc—Str C F Peters Corporation [Vocal Score/Klavierauszug EP 6691] Alberga, Eleanor (b. 1949) _________________________________________________________ Roald Dahl’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs Text by Roald Dahl (English) Becker, John (1886–1961) Narrator(s)—2(II=Picc).2.2(II=B-cl).1.Cbsn—4.2.2.B-tbn.1—5Perc— A Marriage with Space (Stagework No. 3) Hp—Pf—Str / 37' A Drama in colour, light and sound for solo and mass dramatisation, Peters Edition/Hinrichsen [Score/Partitur EP 7566] solo and dance group and orchestra. -

570034Bk Hasse 23/8/10 9:09 PM Page 8

572066bk Hermann EU:570034bk Hasse 23/8/10 9:09 PM Page 8 zu vielen Duowerken des 18.Jahrhunderts fungiert das Cello solistisches Passagenwerk anbelangt. Einmal mehr zeigt sich hier nicht als Begleiter, sondern als gleichberechtigter Hermanns Kompetenz als Streicher. Ein Werk fernab Partner, was thematische Verarbeitung, Stimmführung und jeglicher solistischer und begleitender „Arbeitsteilung“ ! Johann Paul Eichhorn (1787–1861) Die Musikerfamilie Eichhorn stammt aus Coburg in Brüder Eichhorn, nun 8 und 9 Jahre alt, für Louis Spohr in Oberfranken, Deutschland. Johann Paul Eichhorn wurde Kassel, der sich über ihr Können enthusiastisch äußerte. 1787 im Dorf Neuses bei Coburg als Sohn eines Leinwebers 1833 traten die Jungen vor dem Papst auf, anschließend geboren. Auch wenn die Musik im Leben der Eichhorns wurde der elfjährige Ernst zum „Herzoglichen Cammer- Friedrich seit jeher eine bedeutende Rolle spielte, erlernte Johann Paul virtuos“ in Coburg ernannt. 1836 erhielt sein Bruder die Eichhorn nach der Konfirmation den Leinweberberuf, den Auszeichnung „Hofmusicus“. Bis Januar 1837 konzertierten er bis zu seinem 20. Lebensjahr ausübte. Gleichzeitig die Wunderkinder, als Ernsts angegriffene Gesundheit der HERMANN machte er durch eine besondere musikalische Begabung auf Reisetätigkeit Einhalt gebot. Von nun an wirkten sie in sich aufmerksam. Das Violinspiel brachte er sich selbst bei Coburg bei der „Herzoglichen Hof-Capelle“, Ernst als erster um mit Dorfmusikanten Tanzmusik zu spielen. Mit 20 Geiger, der auch die Soli zu übernehmen hatte, Eduard als 3 Capriccios Jahren wurde er zum Militärdienst nach Coburg eingezogen. zweiter Geiger. Später wurden auch die Brüder Albrecht Sein Ziel war eine Anstellung bei der Militärkapelle, und Alexander Eichhorn bei der „Hof-Capelle“ angestellt, weshalb er Horn- und Posaunenunterricht nahm. -

Deutsches Musicalarchiv: Sammlung Klaus Baberg, SMA 0002 Stand: 19.09.2017

Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg, Zentrum für Populäre Kultur und Musik Titelblat Deutsches Musicalarchiv: Sammlung Klaus Baberg, SMA 0002 Stand: 19.09.2017 Deutsches Musicalarchiv: Sammlung Klaus Baberg SMA 0002 Umfang: 5 kleine, 7 große Archivboxen; eine Archivbox in Übergröße; ca. 15 Regalmeter mit Programmheften, Leitz-Ordnern und Einzelmappen; ca. 8 Regalmeter mit Tonträgern. Inhalt: Material zu Musicalaufführungen, v. a. deutschsprachige, der 1970er- bis 2010er Jahre: gut 1000 Programmhefte, Werbeflyer und Presseberichte, 1117 Plakate, rund 200 Fachbücher, Musik- und Filmaufnahmen (362 CDs, 13 DVDs, 26 + 89 Tonkasseten, 32 Videokasseten, 409 Langspielplaten, 23 Singles), Texthefte, Fotos, PR-Material, einzelne Fachzeitschriften. Herkunft: Klaus Baberg hate seine ersten Berührungen mit dem Musical durch die Opereten- und Musical- Fernsehfilme in den 1960er Jahren. Seit 1979 sammelte er intensiv Programmhefte und Programme von Musicals. Verschiedene Exponate aus seiner Sammlung waren auf Ausstellungen zu sehen. Klaus Baberg ist Vorstandsmitglied im 2011 gegründeten Förderverein des Deutschen Musicalarchivs „Freunde und Förderer des Deutschen Musicalarchivs e.V.“ Baberg ist seit 1980 bei der Sparkasse Iserlohn beschäftigt. Hinweis: Der größte Teil der Bestände ist in diesem Dokument erschlossen. Die Bücher und das Notenmaterial der Sammlung sind im Bibliothekskatalog des ZPKM nachgewiesen (Recherche: Eingabe "abl: sbab" in den Suchschlitz). Die Musicalplakate der Sammlung Baberg wurden separiert und werden mit anderen Graphiken aufbewart.