“From Nihilistic Implosion to Creative Explosion”: the Representation of the South Bronx from the Warriors to the Get Down

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Key Pro Date Duration Segment Title Age Morning Edition 10/08/2012 0

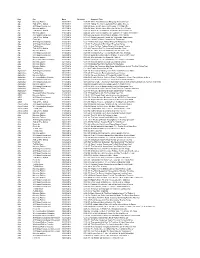

Key Pro Date Duration Segment Title Age Morning Edition 10/08/2012 0:04:09 When Should Seniors Hang Up The Car Keys? Age Talk Of The Nation 10/15/2012 0:30:20 Taking The Car Keys Away From Older Drivers Age All Things Considered 10/16/2012 0:05:29 Home Health Aides: In Demand, Yet Paid Little Age Morning Edition 10/17/2012 0:04:04 Home Health Aides Often As Old As Their Clients Age Talk Of The Nation 10/25/2012 0:30:21 'Elders' Seek Solutions To World's Worst Problems Age Morning Edition 11/01/2012 0:04:44 Older Voters Could Decide Outcome In Volatile Wisconsin Age All Things Considered 11/01/2012 0:03:24 Low-Income New Yorkers Struggle After Sandy Age Talk Of The Nation 11/01/2012 0:16:43 Sandy Especially Tough On Vulnerable Populations Age Fresh Air 11/05/2012 0:06:34 Caring For Mom, Dreaming Of 'Elsewhere' Age All Things Considered 11/06/2012 0:02:48 New York City's Elderly Worry As Temperatures Dip Age All Things Considered 11/09/2012 0:03:00 The Benefit Of Birthdays? Freebies Galore Age Tell Me More 11/12/2012 0:14:28 How To Start Talking Details With Aging Parents Age Talk Of The Nation 11/28/2012 0:30:18 Preparing For The Looming Dementia Crisis Age Morning Edition 11/29/2012 0:04:15 The Hidden Costs Of Raising The Medicare Age Age All Things Considered 11/30/2012 0:03:59 Immigrants Key To Looming Health Aide Shortage Age All Things Considered 12/04/2012 0:03:52 Social Security's COLA: At Stake In 'Fiscal Cliff' Talks? Age Morning Edition 12/06/2012 0:03:49 Why It's Easier To Scam The Elderly Age Weekend Edition Saturday 12/08/2012 -

Various Sugar Hill Story Volume Two Mp3, Flac, Wma

Various Sugar Hill Story Volume Two mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop Album: Sugar Hill Story Volume Two Country: US Released: 1990 MP3 version RAR size: 1237 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1766 mb WMA version RAR size: 1987 mb Rating: 4.3 Votes: 623 Other Formats: WAV VQF MOD MPC AAC MP4 ADX Tracklist 1 –Grandmaster Melle Mel & The Furious Five The Message 2 –West Street Mob Let's Dance 3 –Sugar Hill Gang* Rappers Delight 4 –Sequence* Funk You Up 5 –Treacherous Three Feel The Heartbeat 6 –Sugar Hill Gang* 8th Wonder 7 –Grandmaster Melle Mel & The Furious Five Freedom 8 –Sugar Hill Gang* Apache 9 –The Furious Five meets The Sugar Hill Gang* Showdown 10 –The Mean Machine Disco Dream 11 –Trouble Funk Hey Fellas 12 –Crash Crew* On The Radio Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 0 93382-5248-2 0 Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Sugar Hill Story - Volume Two SHC-5248 Various Sugar Hill Records SHC-5248 US 1989 (Cass, Comp) Related Music albums to Sugar Hill Story Volume Two by Various Sugar Hill Gang - Apache Various - The Greatest Rap Hits Vol 4 Various - Old School Rap Hits I Grandmaster Melle Mel & The Furious Five - Beat Street / Internationally Known Various - Genius Of Rap - The Sugarhill Story Various - The Best Of Grandmaster Flash And Sugar Hill Grandmaster Flash And The Furious 5 - Freedom Sugar Hill Gang - Hot Hot Summer Day Sugarhill Gang - Hot Hot Summer Day Grandmaster Melle Mel & The Furious Five - We Don't Work For Free. -

Boo-Hooray Catalog #10: Flyers

Catalog 10 Flyers + Boo-hooray May 2021 22 eldridge boo-hooray.com New york ny Boo-Hooray Catalog #10: Flyers Boo-Hooray is proud to present our tenth antiquarian catalog, exploring the ephemeral nature of the flyer. We love marginal scraps of paper that become important artifacts of historical import decades later. In this catalog of flyers, we celebrate phenomenal throwaway pieces of paper in music, art, poetry, film, and activism. Readers will find rare flyers for underground films by Kenneth Anger, Jack Smith, and Andy Warhol; incredible early hip-hop flyers designed by Buddy Esquire and others; and punk artifacts of Crass, the Sex Pistols, the Clash, and the underground Austin scene. Also included are scarce protest flyers and examples of mutual aid in the 20th Century, such as a flyer from Angela Davis speaking in Harlem only months after being found not guilty for the kidnapping and murder of a judge, and a remarkably illustrated flyer from a free nursery in the Lower East Side. For over a decade, Boo-Hooray has been committed to the organization, stabilization, and preservation of cultural narratives through archival placement. Today, we continue and expand our mission through the sale of individual items and smaller collections. We encourage visitors to browse our extensive inventory of rare books, ephemera, archives and collections and look forward to inviting you back to our gallery in Manhattan’s Chinatown. Catalog prepared by Evan Neuhausen, Archivist & Rare Book Cataloger and Daylon Orr, Executive Director & Rare Book Specialist; with Beth Rudig, Director of Archives. Photography by Evan, Beth and Daylon. -

Music 18145 Songs, 119.5 Days, 75.69 GB

Music 18145 songs, 119.5 days, 75.69 GB Name Time Album Artist Interlude 0:13 Second Semester (The Essentials Part ... A-Trak Back & Forth (Mr. Lee's Club Mix) 4:31 MTV Party To Go Vol. 6 Aaliyah It's Gonna Be Alright 5:34 Boomerang Aaron Hall Feat. Charlie Wilson Please Come Home For Christmas 2:52 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville O Holy Night 4:44 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville The Christmas Song 4:20 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Let It Snow! Let It Snow! Let It Snow! 2:22 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville White Christmas 4:48 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Such A Night 3:24 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville O Little Town Of Bethlehem 3:56 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Silent Night 4:06 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Louisiana Christmas Day 3:40 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville The Star Carol 2:13 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville The Bells Of St. Mary's 2:44 Aaron Neville's Soulful Christmas Aaron Neville Tell It Like It Is 2:42 Billboard Top R&B 1967 Aaron Neville Tell It Like It Is 2:41 Classic Soul Ballads: Lovin' You (Disc 2) Aaron Neville Don't Take Away My Heaven 4:38 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville I Owe You One 5:33 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Don't Fall Apart On Me Tonight 4:24 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville My Brother, My Brother 4:59 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Betcha By Golly, Wow 3:56 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Song Of Bernadette 4:04 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville You Never Can Tell 2:54 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Bells 3:22 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville These Foolish Things 4:23 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Roadie Song 4:41 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Ain't No Way 5:01 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Grand Tour 3:22 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville The Lord's Prayer 1:58 The Grand Tour Aaron Neville Tell It Like It Is 2:43 Smooth Grooves: The 60s, Volume 3 L.. -

Legacy, Vol. 17, 2017

2017 A Journal of Student Scholarship A Publication of the Sigma Kappa Chapter of Phi Alpha Theta A Publication of the Sigma Kappa & the Southern Illinois University Carbondale History Department & the Southern Illinois University Volume 17 Volume LEGACY • A Journal of Student Scholarship • Volume 17 • 2017 LEGACY Volume 17 2017 A Journal of Student Scholarship Editorial Staff Denise Diliberto Geoff Lybeck Gray Whaley Faculty Editor Hale Yılmaz The editorial staff would like to thank all those who supported this issue of Legacy, especially the SIU Undergradute Student Government, Phi Alpha Theta, SIU Department of History faculty and staff, our history alumni, our department chair Dr. Jonathan Wiesen, the students who submitted papers, and their faculty mentors Professors Jo Ann Argersinger, Jonathan Bean, José Najar, Joseph Sramek and Hale Yılmaz. A publication of the Sigma Kappa Chapter of Phi Alpha Theta & the History Department Southern Illinois University Carbondale history.siu.edu © 2017 Department of History, Southern Illinois University All rights reserved LEGACY Volume 17 2017 A Journal of Student Scholarship Table of Contents The Effects of Collegiate Gay Straight Alliances in the 1980s and 1990s Alicia Mayen ....................................................................................... 1 Students in the Carbondale, Illinois Civil Rights Movement Bryan Jenks ...................................................................................... 15 The Crisis of Legitimacy: Resistance, Unity, and the Stamp Act of 1765, -

“Rapper's Delight”

1 “Rapper’s Delight” From Genre-less to New Genre I was approached in ’77. A gentleman walked up to me and said, “We can put what you’re doing on a record.” I would have to admit that I was blind. I didn’t think that somebody else would want to hear a record re-recorded onto another record with talking on it. I didn’t think it would reach the masses like that. I didn’t see it. I knew of all the crews that had any sort of juice and power, or that was drawing crowds. So here it is two years later and I hear, “To the hip-hop, to the bang to the boogie,” and it’s not Bam, Herc, Breakout, AJ. Who is this?1 DJ Grandmaster Flash I did not think it was conceivable that there would be such thing as a hip-hop record. I could not see it. I’m like, record? Fuck, how you gon’ put hip-hop onto a record? ’Cause it was a whole gig, you know? How you gon’ put three hours on a record? Bam! They made “Rapper’s Delight.” And the ironic twist is not how long that record was, but how short it was. I’m thinking, “Man, they cut that shit down to fifteen minutes?” It was a miracle.2 MC Chuck D [“Rapper’s Delight”] is a disco record with rapping on it. So we could do that. We were trying to make a buck.3 Richard Taninbaum (percussion) As early as May of 1979, Billboard magazine noted the growing popularity of “rapping DJs” performing live for clubgoers at New York City’s black discos.4 But it was not until September of the same year that the trend gar- nered widespread attention, with the release of the Sugarhill Gang’s “Rapper’s Delight,” a fifteen-minute track powered by humorous party rhymes and a relentlessly funky bass line that took the country by storm and introduced a national audience to rap. -

Smith, Troy African & African American Studies Department

Fordham University Masthead Logo DigitalResearch@Fordham Oral Histories Bronx African American History Project 2-3-2006 Smith, Troy African & African American Studies Department. Troy Smith Fordham University Follow this and additional works at: https://fordham.bepress.com/baahp_oralhist Part of the African American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Troy. Interview with the Bronx African American History Project. BAAHP Digital Archive at Fordham University. This Interview is brought to you for free and open access by the Bronx African American History Project at DigitalResearch@Fordham. It has been accepted for inclusion in Oral Histories by an authorized administrator of DigitalResearch@Fordham. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Interviewer: Mark Naison, Andrew Tiedt Interviewee: Troy Smith February 3, 2006 - 1 - Transcriber: Laura Kelly Mark Naison (MN): Hello, this is the 143rd interview of the Bronx African American History Project. It’s February 3, 2006. We’re at Fordham University with Troy Smith who is one of the major collectors of early hip hop materials in the United States and the lead interviewer is Andrew Tiedt, graduate assistant for the Bronx African American History Project. Andrew Tiedt (AT): Okay Troy, first I wanna say thanks for coming in, we appreciate it. Your archive of tapes is probably one of the most impressive I’ve ever seen and especially for this era. Well before we get into that though, I was wondering if you could just tell us a little bit about where you’re from. Where did you grow up? Troy Smith (TS): I grew up in Harlem on 123rd and Amsterdam, the Grant projects, 1966, I’m 39 years old now. -

Riis's How the Other Half Lives

How the Other Half Lives http://www.cis.yale.edu/amstud/inforev/riis/title.html HOW THE OTHER HALF LIVES The Hypertext Edition STUDIES AMONG THE TENEMENTS OF NEW YORK BY JACOB A. RIIS WITH ILLUSTRATIONS CHIEFLY FROM PHOTOGRAPHS TAKEN BY THE AUTHOR Contents NEW YORK CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS 1890 1 of 1 1/18/06 6:25 AM Contents http://www.cis.yale.edu/amstud/inforev/riis/contents.html HOW THE OTHER HALF LIVES CONTENTS. About the Hypertext Edition XII. The Bohemians--Tenement-House Cigarmaking Title Page XIII. The Color Line in New York Preface XIV. The Common Herd List of Illustrations XV. The Problem of the Children Introduction XVI. Waifs of the City's Slums I. Genesis of the Tenements XVII. The Street Arab II. The Awakening XVIII. The Reign of Rum III. The Mixed Crowd XIX. The Harvest of Tare IV. The Down Town Back-Alleys XX. The Working Girls of New York V. The Italian in New York XXI. Pauperism in the Tenements VI. The Bend XXII. The Wrecks and the Waste VII. A Raid on the Stale-Beer Dives XXIII. The Man with the Knife VIII.The Cheap Lodging-Houses XXIV. What Has Been Done IX. Chinatown XXV. How the Case Stands X. Jewtown Appendix XI. The Sweaters of Jewtown 1 of 1 1/18/06 6:25 AM List of Illustrations http://www.cis.yale.edu/amstud/inforev/riis/illustrations.html LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS. Gotham Court A Black-and-Tan Dive in "Africa" Hell's Kitchen and Sebastopol The Open Door Tenement of 1863, for Twelve Families on Each Flat Bird's Eye View of an East Side Tenement Block Tenement of the Old Style. -

Why Hip Hop Began in the Bronx- Lecture for C-Span

Fordham University DigitalResearch@Fordham Occasional Essays Bronx African American History Project 10-28-2019 Why Hip Hop Began in the Bronx- Lecture for C-Span Mark Naison Follow this and additional works at: https://fordham.bepress.com/baahp_essays Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, Cultural History Commons, and the Ethnomusicology Commons Why Hip Hop Began in the Bronx- My Lecture for C-Span What I am about to describe to you is one of the most improbable and inspiring stories you will ever hear. It is about how young people in a section of New York widely regarded as a site of unspeakable violence and tragedy created an art form that would sweep the world. It is a story filled with ironies, unexplored connections and lessons for today. And I am proud to share it not only with my wonderful Rock and Roll to Hip Hop class but with C-Span’s global audience through its lectures in American history series. Before going into the substance of my lecture, which explores some features of Bronx history which many people might not be familiar with, I want to explain what definition of Hip Hop that I will be using in this talk. Some people think of Hip Hop exclusively as “rap music,” an art form taken to it’s highest form by people like Tupac Shakur, Missy Elliot, JZ, Nas, Kendrick Lamar, Wu Tang Clan and other masters of that verbal and musical art, but I am thinking of it as a multilayered arts movement of which rapping is only one component. -

Old Heads Tell Their Stories: from Street Gangs to Street Organizations in New York City

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 412 305 UD 031 930 AUTHOR Brotherton, David C. TITLE Old Heads Tell Their Stories: From Street Gangs to Street Organizations in New York City. SPONS AGENCY Spencer Foundation, Chicago, IL. PUB DATE 1997-00-00 NOTE 35p. PUB TYPE Reports Research (143) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Adults; *Delinquency; Illegal Drug Use; *Juvenile Gangs; *Leadership; Neighborhoods; Role Models; Urban Areas; *Urban Youth IDENTIFIERS *New York (New York); Street Crime ABSTRACT It has been the contention of researchers that the "old heads" (identified by Anderson in 1990 and Wilson in 1987) of the ghettos and barrios of America have voluntarily or involuntarily left the community, leaving behind new generations of youth without adult role models and legitimate social controllers. This absence of an adult strata of significant others adds one more dynamic to the process of social disorganization and social pathology in the inner city. In New York City, however, a different phenomenon was found. Older men (and women) in their thirties and forties who were participants in the "jacket gangs" of the 1970s and/or the drug gangs of the 1980s are still active on the streets as advisors, mentors, and members of the new street organizations that have replaced the gangs. Through life history interviews with 20 "old heads," this paper traces the development of New York City's urban working-class street cultures from corner gangs to drug gangs to street organizations. It also offers a critical assessment of the state of gang theory. Analysis of the development of street organizations in New York goes beyond this study, and would have to include the importance of street-prison social support systems, the marginalization of poor barrio and ghetto youth, the influence of politicized "old heads," the nature of the illicit economy, the qualitative nonviolent evolution of street subcultures, and the changing role of women in the new subculture. -

Hiphop Aus Österreich

Frederik Dörfler-Trummer HipHop aus Österreich Studien zur Popularmusik Frederik Dörfler-Trummer (Dr. phil.), geb. 1984, ist freier Musikwissenschaftler und forscht zu HipHop-Musik und artverwandten Popularmusikstilen. Er promovierte an der Universität für Musik und darstellende Kunst Wien. Seine Forschungen wurden durch zwei Stipendien der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften (ÖAW) so- wie durch den österreichischen Wissenschaftsfonds (FWF) gefördert. Neben seiner wissenschaftlichen Arbeit gibt er HipHop-Workshops an Schulen und ist als DJ und Produzent tätig. Frederik Dörfler-Trummer HipHop aus Österreich Lokale Aspekte einer globalen Kultur Gefördert im Rahmen des DOC- und des Post-DocTrack-Programms der ÖAW. Veröffentlicht mit Unterstützung des Austrian Science Fund (FWF): PUB 693-G Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Na- tionalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http:// dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Dieses Werk ist lizenziert unter der Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Lizenz (BY). Diese Li- zenz erlaubt unter Voraussetzung der Namensnennung des Urhebers die Bearbeitung, Verviel- fältigung und Verbreitung des Materials in jedem Format oder Medium für beliebige Zwecke, auch kommerziell. (Lizenztext: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.de) Die Bedingungen der Creative-Commons-Lizenz gelten nur für Originalmaterial. Die Wieder- verwendung von Material aus anderen Quellen (gekennzeichnet -

Changing Face of Cabaret (Sander)

“The Changing Face of Cabaret” by Roy Sander for Backstage (March 1996) “Do people really do that sort of thing in cabaret?” That was Gregory Henderson’s response when a producer suggested doing his show “Big WInd on Campus” at Don’t Tell Mama. The answer to Henderson’s questIon is a resounding “yes.” Cabaret in America has traditIonally been a venue for sIngers, vocal groups, comedians, revues, and occasIonal specIalty acts, such as female impersonators. But the tImes they have a changed. Clubs in New York abound wIth entertaInment of remarkable diversIty: one- and two-act plays, book musIcals, musIcal comedy, characteriZatIon, performance art, and works so original that they are not easIly classIfiable. The people performIng in cabaret are also a new mIxture, wIth sIngers and comIcs sharing the stage wIth actors and writers. Even artIsts in the more traditIonal forms have seIZed upon this freedom and devised ever more imaginatIve programmIng. While many vocalIsts contInue to do highly satIsfying shows of nothing but songs, others are presentIng highly conceptual evenings In which songs are only one element of a broader agenda. We spoke wIth the creators and performers of several of these shows. In additIon to explaIning why they chose cabaret as theIr venue, some talked about the factors that led them--or drove them to do a show In the first place and about the creatIve route they took to get there, which were often as sIngular as the shows themselves. We first asked booking managers--the people responsIble for choosIng the acts that appear at the clubs--theIr perspectIve on this phenomenon.