Assessment of a Panel of Risk Indicators in Severe Periodontitis Patients

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Probiotic Alternative to Chlorhexidine in Periodontal Therapy: Evaluation of Clinical and Microbiological Parameters

microorganisms Article Probiotic Alternative to Chlorhexidine in Periodontal Therapy: Evaluation of Clinical and Microbiological Parameters Andrea Butera , Simone Gallo * , Carolina Maiorani, Domenico Molino, Alessandro Chiesa, Camilla Preda, Francesca Esposito and Andrea Scribante * Section of Dentistry–Department of Clinical, Surgical, Diagnostic and Paediatric Sciences, University of Pavia, 27100 Pavia, Italy; [email protected] (A.B.); [email protected] (C.M.); [email protected] (D.M.); [email protected] (A.C.); [email protected] (C.P.); [email protected] (F.E.) * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.G.); [email protected] (A.S.) Abstract: Periodontitis consists of a progressive destruction of tooth-supporting tissues. Considering that probiotics are being proposed as a support to the gold standard treatment Scaling-and-Root- Planing (SRP), this study aims to assess two new formulations (toothpaste and chewing-gum). 60 patients were randomly assigned to three domiciliary hygiene treatments: Group 1 (SRP + chlorhexidine-based toothpaste) (control), Group 2 (SRP + probiotics-based toothpaste) and Group 3 (SRP + probiotics-based toothpaste + probiotics-based chewing-gum). At baseline (T0) and after 3 and 6 months (T1–T2), periodontal clinical parameters were recorded, along with microbiological ones by means of a commercial kit. As to the former, no significant differences were shown at T1 or T2, neither in controls for any index, nor in the experimental -

Periodontal Health, Gingival Diseases and Conditions 99 Section 1 Periodontal Health

CHAPTER Periodontal Health, Gingival Diseases 6 and Conditions Section 1 Periodontal Health 99 Section 2 Dental Plaque-Induced Gingival Conditions 101 Classification of Plaque-Induced Gingivitis and Modifying Factors Plaque-Induced Gingivitis Modifying Factors of Plaque-Induced Gingivitis Drug-Influenced Gingival Enlargements Section 3 Non–Plaque-Induced Gingival Diseases 111 Description of Selected Disease Disorders Description of Selected Inflammatory and Immune Conditions and Lesions Section 4 Focus on Patients 117 Clinical Patient Care Ethical Dilemma Clinical Application. Examination of the gingiva is part of every patient visit. In this context, a thorough clinical and radiographic assessment of the patient’s gingival tissues provides the dental practitioner with invaluable diagnostic information that is critical to determining the health status of the gingiva. The dental hygienist is often the first member of the dental team to be able to detect the early signs of periodontal disease. In 2017, the American Academy of Periodontology (AAP) and the European Federation of Periodontology (EFP) developed a new worldwide classification scheme for periodontal and peri-implant diseases and conditions. Included in the new classification scheme is the category called “periodontal health, gingival diseases/conditions.” Therefore, this chapter will first review the parameters that define periodontal health. Appreciating what constitutes as periodontal health serves as the basis for the dental provider to have a stronger understanding of the different categories of gingival diseases and conditions that are commonly encountered in clinical practice. Learning Objectives • Define periodontal health and be able to describe the clinical features that are consistent with signs of periodontal health. • List the two major subdivisions of gingival disease as established by the American Academy of Periodontology and the European Federation of Periodontology. -

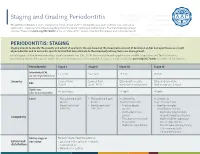

Staging and Grading Periodontitis

Staging and Grading Periodontitis The 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions resulted in a new classification of periodontitis characterized by a multidimensional staging and grading system. The charts below provide an overview. Please visit perio.org/2017wwdc for the complete suite of reviews, case definition papers, and consensus reports. PERIODONTITIS: STAGING Staging intends to classify the severity and extent of a patient’s disease based on the measurable amount of destroyed and/or damaged tissue as a result of periodontitis and to assess the specific factors that may attribute to the complexity of long-term case management. Initial stage should be determined using clinical attachment loss (CAL). If CAL is not available, radiographic bone loss (RBL) should be used. Tooth loss due to periodontitis may modify stage definition. One or more complexity factors may shift the stage to a higher level. Seeperio.org/2017wwdc for additional information. Periodontitis Stage I Stage II Stage III Stage IV Interdental CAL 1 – 2 mm 3 – 4 mm ≥5 mm ≥5 mm (at site of greatest loss) Severity Coronal third Coronal third Extending to middle Extending to middle RBL (<15%) (15% - 33%) third of root and beyond third of root and beyond Tooth loss No tooth loss ≤4 teeth ≥5 teeth (due to periodontitis) Local • Max. probing depth • Max. probing depth In addition to In addition to ≤4 mm ≤5 mm Stage II complexity: Stage III complexity: • Mostly horizontal • Mostly horizontal • Probing depths • Need for -

New Classification of Periodontal Diseases

BDJOpen www.nature.com/bdjopen ARTICLE OPEN New classification of periodontal diseases (NCPD): an application in a sub-Saharan country William Ndjidda Bakari 1, Diabel Thiam1, Ndeye Lira Mbow1, Anna Samb1, Mouhamadou Lamine Guirassy1, Ahmad Moustapha Diallo 1, Abdoulaye Diouf1, Adam Seck Diallo1 and Henri Michel Benoist1 PURPOSE: To determine the clinical and radiological profile of periodontitis according to the 2018 NCPD, in a Dakar (Senegal) based periodontal clinic. METHODS: This is a descriptive study based on patient’s records in the periodontology clinic. The study was conducted between November 2018 and February 2020 (15 months). All periodontitis cases were included in the study. Incomplete records (due to lack of radiographic workup or unusable periodontal charting) were excluded. Periodontitis diagnosis was established based on criteria used in the 2018 NCPD. Statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS version 20.0, with the significance threshold set at 0.05. RESULTS: A total number of 517 patient records were collected during the study period but only 127 periodontitis records were complete. The mean age of participants was 46.8 ± 13.8 years and 63.8% of participants were males. The mean plaque index and bleeding on probing (BOP) were 74% ± 21.3 and 58.1% ± 25.1, respectively. The mean maximum clinical attachment loss was 8.7 mm ±2.7, with a probing depth greater than 6 mm present in 50.4% of the sample. The median number of missing teeth was 3 (interquartile range 5–1). Pathological mobility was present in 60.6% of the patients and 78.0% had occlusion problems. -

TO GRAFT OR NOT to GRAFT? an UPDATE on GINGIVAL GRAFTING DIAGNOSIS and TREATMENT MODALITIES Richard J

October 2018 Gingival Recession Autogenous Soft Tissue Grafting Tissue Engineering JournaCALIFORNIA DENTAL ASSOCIATION TO GRAFT OR NOT TO GRAFT? AN UPDATE ON GINGIVAL GRAFTING DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT MODALITIES Richard J. Nagy, DDS Ready to save 20%? Let’s go! Discover The Dentists Supply Company’s online shopping experience that delivers CDA members the supplies they need at discounts that make a difference. Price compare and save at tdsc.com. Price comparisons are made to the manufacturer’s list price. Actual savings on tdsc.com will vary on a product-by-product basis. Oct. 2018 CDA JOURNAL, VOL 46, Nº10 DEPARTMENTS 605 The Editor/Nothing but the Tooth 607 Letter to the Editor 609 Impressions 663 RM Matters/Are Your Patients Who They Say They Are? Preventing Medical Identity Theft 667 Regulatory Compliance/OSHA Regulations: Fire Extinguishers, Eyewash, Exit Signs 609 674 Tech Trends FEATURES 615 To Graft or Not To Graft? An Update on Gingival Grafting Diagnosis and Treatment Modalities An introduction to the issue. Richard J. Nagy, DDS 617 Gingival Recession: What Is It All About? This article reviews factors that enhance the risk for gingival recession, describes at what stage interceptive treatment should be recommended and expected outcomes. Debra S. Finney, DDS, MS, and Richard T. Kao, DDS, PhD 625 Autogenous Soft Tissue Grafting for the Treatment of Gingival Recession This article reviews the use of autogenous soft tissue grafting for root coverage. Advantages and disadvantages of techniques are discussed. Case types provide indications for selection and treatment. Elissa Green, DMD; Soma Esmailian Lari, DMD; and Perry R. -

Periodontal Parameters and Tooth Loss Were Associated with C- Reactive Protein and Leukocyte Counts in Adult Population Aged 50 Or Older

Oral Biology Research, 2017; March 31, 41(1):15-22 Copyright ⓒ 2017, Oral Biology Research Institute DOI: 10.21851/obr.41.01.201703.15 ORAL BIOLOGY Original Article RESEARCH Periodontal parameters and tooth loss were associated with C- reactive protein and leukocyte counts in adult population aged 50 or older Ji-Hyun Lee1, Min-Ho Shin2*, Sun-Seog Kweon2,3, Young-Hoon Lee4, Ok-Joon Kim5, Young-Joon Kim1, Hyun- Ju Chung1, and Ok-Su Kim1* 1Department of Periodontology, School of Dentistry, Dental Science Research Institute, Chonnam National University, Gwangju 61186, Republic of Korea 2Department of Preventive Medicine, Chonnam National University Medical School, Gwangju 61469, Republic of Korea 3Jeonnam Regional Cancer Center, Chonnam National University Hwasun Hospital, Hwasun 58128, Republic of Korea 4Department of Preventive Medicine & Institute of Wonkwang Medical Science, Wonkwang University School of Med- icine, Iksan 54538, Republic of Korea 5Department of Oral Pathology, School of Dentistry, Dental Science Research Institute, Chonnam National University, Gwangju 61186, Republic of Korea (Received Nov 8, 2016; Revised version received Jan 12, 2017; Accepted Feb 7, 2017) ABSTRACT ············································································································································································· The association between periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease (CVD) has received considerable attention. This study investigated the correlation between tooth loss (the chief -

Are You Suprised ?

Pretest 2003 with answers/explanations DAPE 761 – Advanced Periodontics Name: ________________________ Dr. Dwight E. McLeod October 24, 2003 PRETEST 1. Gingivectomy is a surgical procedure that is performed to eliminate periodontal pockets and includes eshaping of the gingiva. Gingivoplasty is a surgical procedure that includes reshaping of the gingiva to create physiologic contours with the sole purpose of recontouring the gingiva in the absence of pockets. A. Both statements are true.* B. Both statements are false. C. The first statement is true and the second statement is false. D. The first statement is false and the second statement is true. Gingivectomy means excision of the gingiva. By removing the pocket wall, gingivectomy provides visibility and accessibility for complete calculus removal and thorough smoothing of the roots, creating a favorable environment for gingival healing and restoration of a physiologic gingival contour. Gingivoplasty is similar to gingivectomy, but its purpose is different. Gingivectomy is performed to eliminate periodontal pockets and includes reshaping as part of the technique. Gingivoplasty is a reshaping of the gingival to create physiologic gingival contours, with the sole purpose of recontouring the gingiva in the absence of pockets. 2. Indications for the gingivectomy procedure include: A. Elimination of suprabony pockets. B. Elimination of gingival enlargements. C. Elimination of suprabony periodontal abscesses. D. A and B E. All of the above* The gingivectomy procedure may be performed for (1) elimination of suprabony pockets, regardless of their depth, if the pocket wall is fibrous and firm, (2) elimination of gingival enlargement, and (3) elimination of suprabony periodontal abscesses. 3. Contraindications for the gingivectomy procedure include: A. -

Faculty of Dentistry Department of Oral Medicine, Periodontology, Oral Diagnosis and Oral Radiology

Faculty of Dentistry Department of Oral Medicine, Periodontology, Oral Diagnosis and Oral Radiology LEVELS OF MATRIX METALLOPROTEINASE-8 IN GINGIVAL CREVICULAR FLUID AFTER INTRAPOCKET APPLICATION OF CYMBOPOGON CITRATUS GEL ADJUNCTIVE TO NON-SURGICAL TREATMENT IN PATIENTS WITH MODERATE PERIODONTITIS. Protocol for M. Sc. Degree In oral medicine, periodontology, oral diagnosis, and oral radiology Academic Year 2019-2020 17th October 2019 Name of Candidate: Nadein Abd Elnasser El. Sharif Supervision Committee: 1. Prof. Dr. Ahmed M Hommos. Prof. of Oral Medicine, Periodontology, Oral Diagnosis and Oral Radiology. Department of Oral Medicine, Periodontology, Oral Diagnosis and Oral Radiology. Faculty of Dentistry- Alexandria University. 2. Dr. Souzy Kamal Anwar. Lecturer of Oral Medicine, Periodontology, Oral Diagnosis and Oral Radiology. Department of Oral Medicine, Periodontology, Oral Diagnosis and Oral Radiology. Faculty of Dentistry- Alexandria University. 3. Dr. Riham Mohamed El-Moslemany. Lecturer of Pharmaceutics. Department of Pharmaceutics. Faculty of Pharmacy- Alexandria University. 4. Dr. Neveen Lewis Mikhael. Lecturer of Clinical Pathology. Department of Clinical Pathology. Faculty of Medicine- Alexandria University. CONTENT ABSTRACT ........................................................................................................................ 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 2 AIM OF THE WORK ........................................................................................................ -

Peri-Implant Tissue Measurement Terminologies in Health and Disease: a Critical Insight Anil Akansha1, Kharidhi L Vandana2

REVIEW ARTICLE Peri-implant Tissue Measurement Terminologies in Health and Disease: A Critical Insight Anil Akansha1, Kharidhi L Vandana2 ABSTRACT The implantology field has been a center of interest for several clinicians, teachers, and students globally. Amidst these fast-moving tissues, the terminologies for peri-implant measurements and the standard concept of measurement guidelines remain obscure and compromised. Unfortunately, the pioneering implantologists have not made an adequate attempt to address the existing deficiencies in guidelines, terminologies, and measurements pertaining to peri-implant tissues in health and disease. There is a lack of consistency across definitions of peri-implant osteitis in the literature, and the diagnostic criteria are not clear. Most of the published strategies for peri-implant osteitis therapy are mainly based on treatments used for teeth with periodontitis. The required platform to diagnose, classify, treat and comprehensive terminologies are the need of the hour in the implant related world. Hence, an attempt is made in this paper to briefly address the peri-implant-related clinical measurements, peri-implant disease classification, and its treatment strategies. Keywords: Peri-implant measurements, Peri-implant osteitis, Peri-implant osteitis therapy, Periodontitis. CODS Journal of Dentistry (2018): 10.5005/jp-journals-10063-0037 INTRODUCTION 1,2Department of Periodontics, College of Dental Sciences, Davangere, Implantology is growing tremendously in clinical practice and in Karnataka, India the academic front. Various systems and techniques have been Corresponding Author: Kharidhi L Vandana, Department of researched for better implant bone stability to benefit the patient at Periodontics, College of Dental Sciences, Davangere, Karnataka, India, a faster pace. The implantology field has been a center of interest for Phone: +91 9448393364, e-mail: [email protected] several clinicians, teachers, and students globally. -

Inventory #: 01 Page 1 of 3

Inventory #: 01 Page 1 of 3 CDT CODE ACTION REQUEST Part 1 – Submitter Information A. Contact Information (Action Requestor) Date Submitted: 10/17/2019 Name: DentalCodeology Consortium B. Does this request represent the official position of either a dental organization or a recognized dental specialty, or a third-party payer or administrator, or the manufacturer/supplier of a product? Yes > ☒ If Yes, The Oral Cancer Foundation Name: No > ☐ Part 2 – Submission Details 1. Action Affected Code New ☒ Revise ☐ Delete ☐ (Mark one only) (Revise or Delete only) 2. Full nomenclature and descriptor (For “Revise” mark-up as follows: added text – blue underline; deleted text – red strike-through; unchanged text – black) Nomenclature an enhanced oral cancer examination to include a comprehensive risk Required for all assessment, visual and tactile, intra/extra oral and oropharyngeal screening to “New” identify abnormalities Descriptor This procedure involves a detailed risk assessment to include a verbal inquiry, and/or an updated or new written health history, with a visual inspection using operatory Optional for “New”; enter “None” if no lighting/loupes, and palpation, which are the necessary techniques used in oral and descriptor oropharyngeal cancer evaluations. NOTICE TO PREPARER AND SUBMITTER: All requested information in Parts 1-3 is required; limited exceptions are noted. Cells where information is entered have white backgrounds and will automatically expand as needed. Mark cells with “check boxes” (☐) by moving the cursor over the box and making a “left-click”. Completed Request must be submitted in unprotected MSWord® format via email to [email protected]. A submission will be returned for correction if it is: a) not an unprotected MS Word document; b) not on the current Action Request format; or c) it is missing “Required” information. -

Clinical Practice Guideline for Periodontics

Clinical Practice Guideline For Periodontics © MOH- Oral Health CSN –Periodontics-2010 Page 1 of 16 INTRODUCTION: Periodontal Diseases. This term, in its widest sense, includes all pathological conditions of the periodontium. It is however, commonly used with reference to those inflammatory disease which are plaque induced and which affect the marginal periodontium: Periodontitis and Gingivitis Gingivitis: Gingivitis is the mildest form of periodontal disease. It involves inflammation confined to the gingival tissues. • There is no loss of connective tissue attachment • A gingival pocket may be present Periodontitis: Is the apical extension of gingival inflammation to involve the supporting tissues. Destruction of the fibre attachment results in periodontal pockets. • it leads to loss of connective tissue attachment • which in turn results in loss of supporting alveolar bone © MOH- Oral Health CSN –Periodontics-2010 Page 2 of 16 OBJECTIVES OF TREATMENT • Relief of symptoms • Restoration of periodontal health • Restoration and maintenance of function and aesthetic PERIODONTAL ASSESSMENT Assessment of medical history Assessment of dental history Assessment of periodontal risk factors Assessment of extra-oral and intraoral structures and tissues 1. Age Assessment of teeth 2. Gender 3. Medications 1. Mobility 4. Presence of plaque and calculus (quantity and 2. Caries distribution) 3. Furcation involvement 5. Smoking 4. Position in dental arch and within alveolus 6. Race/Ethnicity 5. Occlusal relationships 7. Systemic disease (eg, diabetes) 6. Evidence of trauma from occlusion 8. Oral hygiene 9. Socio-economic status and level of education Assessment of periodontal soft tissues 1. Colour 2. Contour 3. Consistency (fibrotic or oedematous) 4. Presence of purulence (suppuration) 5. -

NEW CLASSIFICATION of PERIODONTAL and PERI-IMPLANT DISEASES Guest Editors: Mariano Sanz Y Panos N

Scientific journal of the Period I, Year V, n.º 15 Sociedad Española de Periodoncia Editor: Ion Zabalegui 2019 / 15 International Edition periodonciaclínica NEW CLASSIFICATION OF PERIODONTAL AND PERI-IMPLANT DISEASES Guest editors: Mariano Sanz y Panos N. Papapanou ADVERTISING Presentation ANTONIO BUJALDÓN, PRESIDENT OF SEPA 2019-2022 THIS IS THE FIRST EDITORIAL of Periodoncia Clínica of the Before ending this editorial, it is essential to dedicate some SEPA presidential mandate for 2019-2022. It is a huge honour lines of recognition and thanks to the active and committed SEPA to start with a monographic issue on the New Classification members involved with Periodoncia Clínica over the four years that of Periodontal and Peri-implant Diseases, fruit of the work of have passed since the creation of this informative publication, which the World Workshop held in 2017 by the American Academy has consolidated a style and friendly way of strengthening and of Periodontology (AAP) and the European Federation of facilitating professional access to knowledge, under the values of Periodontology (EFP), to which SEPA is proud to belong as one of its rigour, innovation, and excellence that are the hallmarks of SEPA. most dynamic members. Ion Zabalegui, editor of Periodoncia Clínica, together with The rejoicing increases by having the brilliant collaboration as associate editors Laurence Adriaens, Andrés Pascual, and Jorge guest editors of Panos N. Papapanou and Mariano Sanz, the latter Serrano, deserve a display of immense gratitude from all SEPA of