New Classification of Periodontal Diseases

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Probiotic Alternative to Chlorhexidine in Periodontal Therapy: Evaluation of Clinical and Microbiological Parameters

microorganisms Article Probiotic Alternative to Chlorhexidine in Periodontal Therapy: Evaluation of Clinical and Microbiological Parameters Andrea Butera , Simone Gallo * , Carolina Maiorani, Domenico Molino, Alessandro Chiesa, Camilla Preda, Francesca Esposito and Andrea Scribante * Section of Dentistry–Department of Clinical, Surgical, Diagnostic and Paediatric Sciences, University of Pavia, 27100 Pavia, Italy; [email protected] (A.B.); [email protected] (C.M.); [email protected] (D.M.); [email protected] (A.C.); [email protected] (C.P.); [email protected] (F.E.) * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.G.); [email protected] (A.S.) Abstract: Periodontitis consists of a progressive destruction of tooth-supporting tissues. Considering that probiotics are being proposed as a support to the gold standard treatment Scaling-and-Root- Planing (SRP), this study aims to assess two new formulations (toothpaste and chewing-gum). 60 patients were randomly assigned to three domiciliary hygiene treatments: Group 1 (SRP + chlorhexidine-based toothpaste) (control), Group 2 (SRP + probiotics-based toothpaste) and Group 3 (SRP + probiotics-based toothpaste + probiotics-based chewing-gum). At baseline (T0) and after 3 and 6 months (T1–T2), periodontal clinical parameters were recorded, along with microbiological ones by means of a commercial kit. As to the former, no significant differences were shown at T1 or T2, neither in controls for any index, nor in the experimental -

Assessment of a Panel of Risk Indicators in Severe Periodontitis Patients

Assessment of a panel of risk indicators in severe periodontitis patients Ciobanu L.¹, Miricescu D. ², Didilescu A.³, Țărmure V.4 ¹PhD Student in Dental Medicine, Division of Microbiology, Faculty of Dental Medicine, Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Bucharest, Romania ²Senior Lecturer, Division of Biochemistry, Faculty of Dental Medicine, Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Bucharest, Romania ³Professor, Division of Embryology, Faculty of Dental Medicine, Carol Davila University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Bucharest, Romania 4Associate Professor, Department of Orthodontics, Faculty of Dental Medicine, Iuliu Hațieganu University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Cluj-Napoca, Romania Correspondence to: Name: Ciobanu Lidia Address: Blvd. Camil Ressu 49, Bl. H26, Sc. D, Ap.61, Bucharest, Romania Phone: +40 724962500 E-mail address: [email protected] Abstract Aim and objectives The purpose of this study was to analyse a panel of risk indicators in a group of twenty-two patients with severe periodontitis. We also aimed to test possible associations between these indicators and the severity of periodontitis assessed by clinical attachment loss (CAL) mean values. Material and methods Periodontal status was assessed based on the CDC/AAP periodontitis case definition for population-based studies. Risk indicators, including age, gender, weight and height, level of education, and smoking habits, were recorded. Salivary cortisol level, as a marker of chronic stress, was also measured. Results The mean age of the patients was 44.86 (SD 12.81; range 24 to 72). Ten females (45.5%) were enrolled. Testing possible associations between risk indicators and CAL mean values showed no statistical significant correlations, although trends of positive correlations were found between males, BMI, and CAL, respectively Conclusions The present results suggest that a high BMI, as well as masculine gender, could have been important risk factors for severe periodontitis in this study group. -

Periodontal Health, Gingival Diseases and Conditions 99 Section 1 Periodontal Health

CHAPTER Periodontal Health, Gingival Diseases 6 and Conditions Section 1 Periodontal Health 99 Section 2 Dental Plaque-Induced Gingival Conditions 101 Classification of Plaque-Induced Gingivitis and Modifying Factors Plaque-Induced Gingivitis Modifying Factors of Plaque-Induced Gingivitis Drug-Influenced Gingival Enlargements Section 3 Non–Plaque-Induced Gingival Diseases 111 Description of Selected Disease Disorders Description of Selected Inflammatory and Immune Conditions and Lesions Section 4 Focus on Patients 117 Clinical Patient Care Ethical Dilemma Clinical Application. Examination of the gingiva is part of every patient visit. In this context, a thorough clinical and radiographic assessment of the patient’s gingival tissues provides the dental practitioner with invaluable diagnostic information that is critical to determining the health status of the gingiva. The dental hygienist is often the first member of the dental team to be able to detect the early signs of periodontal disease. In 2017, the American Academy of Periodontology (AAP) and the European Federation of Periodontology (EFP) developed a new worldwide classification scheme for periodontal and peri-implant diseases and conditions. Included in the new classification scheme is the category called “periodontal health, gingival diseases/conditions.” Therefore, this chapter will first review the parameters that define periodontal health. Appreciating what constitutes as periodontal health serves as the basis for the dental provider to have a stronger understanding of the different categories of gingival diseases and conditions that are commonly encountered in clinical practice. Learning Objectives • Define periodontal health and be able to describe the clinical features that are consistent with signs of periodontal health. • List the two major subdivisions of gingival disease as established by the American Academy of Periodontology and the European Federation of Periodontology. -

Probing Techniques Message Board, Page 6 HT Inthisissue Layout 1 6/25/13 2:44 PM Page 1

HT July Cover_Layout 1 6/25/13 3:01 PM Page 1 Dental Hygiene Diagnosis Perio Reports Vol. 25 No. page 1 page 3 July 2013 Probing Techniques Message Board, page 6 HT_InThisIssue_Layout 1 6/25/13 2:44 PM Page 1 hygienetown in this section Dental Hygiene Diagnosis by Trisha E. O’Hehir, RDH, MS Hygienetown Editorial Director To some, the word “diagnosis” is taboo for hygien- ists to even consider using, let alone doing! Diagnosis is simply recognizing the signs and symptoms of disease, something all hygienists are required to do to take their licensing exam. Hygienists also must practice this in the clinical setting to provide care for patients. If a hygienist can’t tell the difference between health and disease, keeping a clinical position will be difficult. Those who don’t want RDHs to “diagnose” must instead want a robot to simply “scale teeth.” Every dentist I’ve know wants the RDH employed in the practice to “actually have a brain,” to quote Dr. Michael Rethman. Providing dental hygiene care involves critical thinking to assess the health of each individual patient. A wide variety of information is gathered to determine health, disease and individual risk factors presented by each patient. With the identi- fication of the dental hygiene diagnosis, the dental hygiene treatment plan can be devised and followed by the RDH. The dental hygiene diagnosis and treatment plan are part of the comprehensive dental diagnosis and treatment plan created by the dentist. Working as colleagues, the dentist and dental hygienist gather information necessary to accurately assess the health of each patient and provide the necessary treatment, prevention and maintenance care. -

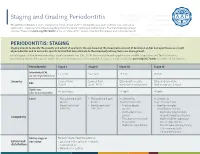

Staging and Grading Periodontitis

Staging and Grading Periodontitis The 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions resulted in a new classification of periodontitis characterized by a multidimensional staging and grading system. The charts below provide an overview. Please visit perio.org/2017wwdc for the complete suite of reviews, case definition papers, and consensus reports. PERIODONTITIS: STAGING Staging intends to classify the severity and extent of a patient’s disease based on the measurable amount of destroyed and/or damaged tissue as a result of periodontitis and to assess the specific factors that may attribute to the complexity of long-term case management. Initial stage should be determined using clinical attachment loss (CAL). If CAL is not available, radiographic bone loss (RBL) should be used. Tooth loss due to periodontitis may modify stage definition. One or more complexity factors may shift the stage to a higher level. Seeperio.org/2017wwdc for additional information. Periodontitis Stage I Stage II Stage III Stage IV Interdental CAL 1 – 2 mm 3 – 4 mm ≥5 mm ≥5 mm (at site of greatest loss) Severity Coronal third Coronal third Extending to middle Extending to middle RBL (<15%) (15% - 33%) third of root and beyond third of root and beyond Tooth loss No tooth loss ≤4 teeth ≥5 teeth (due to periodontitis) Local • Max. probing depth • Max. probing depth In addition to In addition to ≤4 mm ≤5 mm Stage II complexity: Stage III complexity: • Mostly horizontal • Mostly horizontal • Probing depths • Need for -

TO GRAFT OR NOT to GRAFT? an UPDATE on GINGIVAL GRAFTING DIAGNOSIS and TREATMENT MODALITIES Richard J

October 2018 Gingival Recession Autogenous Soft Tissue Grafting Tissue Engineering JournaCALIFORNIA DENTAL ASSOCIATION TO GRAFT OR NOT TO GRAFT? AN UPDATE ON GINGIVAL GRAFTING DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT MODALITIES Richard J. Nagy, DDS Ready to save 20%? Let’s go! Discover The Dentists Supply Company’s online shopping experience that delivers CDA members the supplies they need at discounts that make a difference. Price compare and save at tdsc.com. Price comparisons are made to the manufacturer’s list price. Actual savings on tdsc.com will vary on a product-by-product basis. Oct. 2018 CDA JOURNAL, VOL 46, Nº10 DEPARTMENTS 605 The Editor/Nothing but the Tooth 607 Letter to the Editor 609 Impressions 663 RM Matters/Are Your Patients Who They Say They Are? Preventing Medical Identity Theft 667 Regulatory Compliance/OSHA Regulations: Fire Extinguishers, Eyewash, Exit Signs 609 674 Tech Trends FEATURES 615 To Graft or Not To Graft? An Update on Gingival Grafting Diagnosis and Treatment Modalities An introduction to the issue. Richard J. Nagy, DDS 617 Gingival Recession: What Is It All About? This article reviews factors that enhance the risk for gingival recession, describes at what stage interceptive treatment should be recommended and expected outcomes. Debra S. Finney, DDS, MS, and Richard T. Kao, DDS, PhD 625 Autogenous Soft Tissue Grafting for the Treatment of Gingival Recession This article reviews the use of autogenous soft tissue grafting for root coverage. Advantages and disadvantages of techniques are discussed. Case types provide indications for selection and treatment. Elissa Green, DMD; Soma Esmailian Lari, DMD; and Perry R. -

Periodontal Parameters and Tooth Loss Were Associated with C- Reactive Protein and Leukocyte Counts in Adult Population Aged 50 Or Older

Oral Biology Research, 2017; March 31, 41(1):15-22 Copyright ⓒ 2017, Oral Biology Research Institute DOI: 10.21851/obr.41.01.201703.15 ORAL BIOLOGY Original Article RESEARCH Periodontal parameters and tooth loss were associated with C- reactive protein and leukocyte counts in adult population aged 50 or older Ji-Hyun Lee1, Min-Ho Shin2*, Sun-Seog Kweon2,3, Young-Hoon Lee4, Ok-Joon Kim5, Young-Joon Kim1, Hyun- Ju Chung1, and Ok-Su Kim1* 1Department of Periodontology, School of Dentistry, Dental Science Research Institute, Chonnam National University, Gwangju 61186, Republic of Korea 2Department of Preventive Medicine, Chonnam National University Medical School, Gwangju 61469, Republic of Korea 3Jeonnam Regional Cancer Center, Chonnam National University Hwasun Hospital, Hwasun 58128, Republic of Korea 4Department of Preventive Medicine & Institute of Wonkwang Medical Science, Wonkwang University School of Med- icine, Iksan 54538, Republic of Korea 5Department of Oral Pathology, School of Dentistry, Dental Science Research Institute, Chonnam National University, Gwangju 61186, Republic of Korea (Received Nov 8, 2016; Revised version received Jan 12, 2017; Accepted Feb 7, 2017) ABSTRACT ············································································································································································· The association between periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease (CVD) has received considerable attention. This study investigated the correlation between tooth loss (the chief -

Are You Suprised ?

Pretest 2003 with answers/explanations DAPE 761 – Advanced Periodontics Name: ________________________ Dr. Dwight E. McLeod October 24, 2003 PRETEST 1. Gingivectomy is a surgical procedure that is performed to eliminate periodontal pockets and includes eshaping of the gingiva. Gingivoplasty is a surgical procedure that includes reshaping of the gingiva to create physiologic contours with the sole purpose of recontouring the gingiva in the absence of pockets. A. Both statements are true.* B. Both statements are false. C. The first statement is true and the second statement is false. D. The first statement is false and the second statement is true. Gingivectomy means excision of the gingiva. By removing the pocket wall, gingivectomy provides visibility and accessibility for complete calculus removal and thorough smoothing of the roots, creating a favorable environment for gingival healing and restoration of a physiologic gingival contour. Gingivoplasty is similar to gingivectomy, but its purpose is different. Gingivectomy is performed to eliminate periodontal pockets and includes reshaping as part of the technique. Gingivoplasty is a reshaping of the gingival to create physiologic gingival contours, with the sole purpose of recontouring the gingiva in the absence of pockets. 2. Indications for the gingivectomy procedure include: A. Elimination of suprabony pockets. B. Elimination of gingival enlargements. C. Elimination of suprabony periodontal abscesses. D. A and B E. All of the above* The gingivectomy procedure may be performed for (1) elimination of suprabony pockets, regardless of their depth, if the pocket wall is fibrous and firm, (2) elimination of gingival enlargement, and (3) elimination of suprabony periodontal abscesses. 3. Contraindications for the gingivectomy procedure include: A. -

Faculty of Dentistry Department of Oral Medicine, Periodontology, Oral Diagnosis and Oral Radiology

Faculty of Dentistry Department of Oral Medicine, Periodontology, Oral Diagnosis and Oral Radiology LEVELS OF MATRIX METALLOPROTEINASE-8 IN GINGIVAL CREVICULAR FLUID AFTER INTRAPOCKET APPLICATION OF CYMBOPOGON CITRATUS GEL ADJUNCTIVE TO NON-SURGICAL TREATMENT IN PATIENTS WITH MODERATE PERIODONTITIS. Protocol for M. Sc. Degree In oral medicine, periodontology, oral diagnosis, and oral radiology Academic Year 2019-2020 17th October 2019 Name of Candidate: Nadein Abd Elnasser El. Sharif Supervision Committee: 1. Prof. Dr. Ahmed M Hommos. Prof. of Oral Medicine, Periodontology, Oral Diagnosis and Oral Radiology. Department of Oral Medicine, Periodontology, Oral Diagnosis and Oral Radiology. Faculty of Dentistry- Alexandria University. 2. Dr. Souzy Kamal Anwar. Lecturer of Oral Medicine, Periodontology, Oral Diagnosis and Oral Radiology. Department of Oral Medicine, Periodontology, Oral Diagnosis and Oral Radiology. Faculty of Dentistry- Alexandria University. 3. Dr. Riham Mohamed El-Moslemany. Lecturer of Pharmaceutics. Department of Pharmaceutics. Faculty of Pharmacy- Alexandria University. 4. Dr. Neveen Lewis Mikhael. Lecturer of Clinical Pathology. Department of Clinical Pathology. Faculty of Medicine- Alexandria University. CONTENT ABSTRACT ........................................................................................................................ 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 2 AIM OF THE WORK ........................................................................................................ -

The Role of Technology in Periodontal Evaluation and Treatment Acceptance a Peer-Reviewed Publication Written by William L

Earn 4 CE credits This course was written for dentists, dental hygienists, and assistants. The Role of Technology in Periodontal Evaluation and Treatment Acceptance A Peer-Reviewed Publication Written by William L. Balanoff, DDS, MS, FICD and Cris Duval, RDH PennWell is an ADA CERP Recognized Provider 1-888-INEEDCE This course has been made possible through an unrestricted educational grant. The cost of this CE course is $59.00 for 4 CE credits. Cancellation/Refund Policy: Any participant who is not 100% satisfied with this course can request a full refund by contacting PennWell in writing. Educational Objectives leukin-1 can be found inside atherosclerotic plaque; TNF-α Upon completion of this course, the clinician will be able to antagonizes insulin.12 Interleukin-6, which is also produced, do the following: increases the production of fi brinogen (which is also associated 1. Know the prevalence of periodontal disease and with the creation of thrombi).13 Unhindered, once pockets and understand treatment needs. subgingival plaque are present, home-care is ineffective, irre- 2. Be knowledgeable about treatment obstacles. spective of the degree of care. Professional care is required.14 3. Understand the technology options available that assist in probing, charting and treatment planning and the Periodontal Disease Prevalence advantages of these. Periodontal disease is prevalent. Gingivitis around at least 4. Understand the role of technology in patient treatment three to four teeth was estimated in the NHANES III study to acceptance, practice-building and risk management. be experienced by 50 percent of adults.15 The majority of the adult population suffers from mild to moderate chronic peri- Abstract odontitis, and advanced periodontal disease affects between 5 The prevalence of periodontal disease and estimates of pro- and 15 percent of adults.16,17 More than 50 percent of adults vided treatment are indicative of treatment needs. -

Detection and Diagnosis of Periodontal Conditions Amenable to Prevention Philip M Preshaw from Prevention in Practice - Making It Happen Cape Town, South Africa

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Springer - Publisher Connector Preshaw BMC Oral Health 2015, 15(Suppl 1):S5 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6831/15/S1/S5 PROCEEDINGS Open Access Detection and diagnosis of periodontal conditions amenable to prevention Philip M Preshaw From Prevention in practice - making it happen Cape Town, South Africa. 29 June 2014 Abstract Gingivitis and chronic periodontitis are highly prevalent chronic inflammatory diseases. Gingivitis affects the majority of people, and advanced periodontitis is estimated to affect 5-15% of adults. The detection and diagnosis of these common diseases is a fundamentally important component of oral health care. All patients should undergo periodontal assessment as part of routine oral examination. Periodontal screening using methods such as the Basic Periodontal Examination/Community Periodontal Index or Periodontal Screening Record should be performed for all new patients, and also on a regular basis as part of ongoing oral health care. If periodontitis is identified, full periodontal assessment is required, involving recording of full mouth probing and bleeding data, together with assessment of other relevant parameters such as plaque levels, furcation involvement, recession and tooth mobility. Radiographic assessment of alveolar bone levels is driven by the clinical situation, and is required to assess bone destruction in patients with periodontitis. Risk assessment (such as assessing diabetes status and smoking) and risk management (such as promoting smoking cessation) should form a central component of periodontal therapy. This article provides guidance to the oral health care team regarding methods and frequencies of appropriate clinical and radiographic examinations to assess periodontal status, to enable appropriate detection and diagnosis of periodontal conditions. -

Accuracy of Periodontal Probing Depth and Calculus Detection Through the Use of the Kinoshita Nissin Periodontal Dental Model

Tufts University School of Dental Medicine Accuracy of Periodontal Probing Depth and Calculus Detection Through the use of the Kinoshita Nissin Periodontal Dental Model Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Science. Daniel Coleman Department of Periodontology April 2014 1 Thesis Committee Dr. Paul Levi Principal Investigator – Associate Professor, Department of Periodontology, Tufts University School of Dental Medicine Dr. James Hanley Dean of Clinical Affairs and Chair, Department of Periodontology, Tufts University School of Dental Medicine Dr. Robert Rudy Clinical Associate Professor, Department of Periodontology, Tufts University School of Dental Medicine Dr. Eduardo Marcuschamer Clinical Instructor, Department of Periodontology, Tufts University School of Dental Medicine Dr. Matthew Finkelman Associate Professor, Department of Public Health and Community Service, Tufts University School of Dental Medicine 2 Table of Contents Thesis Committee…………………………………………………………………...2 Abstract……………………………………………………………………………...4 Introduction………………………………………………………………………….6 Specific Aims and Hypothesis………………………………………………………13 Research Design and Methods………………………………………………………14 Results……………………………………………………………………………….24 Discussion…………………………………………………………………………...29 References…………………………………………………………………………...37 Appendix A: Copy of Survey Instrument…………………………………………...41 Appendix B: Lecture Outline………………………………………………………..43 Appendix C: Examination Key……………………………………………………...44 3 Abstract: Dental education is a continually