1 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background of the Study Indonesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women As Hungry Ghost Figures and Kitchen God in Selected Amy Tan's

International Journal of Business and Social Science Vol. 2 No. 15; August 2011 FOOD, FAMILY AND DESIRE:-WOMEN AS HUNGRY GHOST FIGURES AND KITCHEN GOD IN SELECTED AMY TAN’S NOVELS BELINDA MARIE BALRAJ Pusat PengajianUmum Dan Bahasa Universiti Pertahanan Nasional Malaysia Kem Sungai Besi, 57000 Kuala Lumpur Malaysia E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT This study focuses Amy Tan’s The Joy Luck Club, and The Kitchen God’s Wife where communication within family members is accompanied by and sometimes enacted through food imagery. This study focuses specifically on hunger through imagery indicative of the Buddhist mythological figure known as the Hungry Ghost. However this study does not comply with the Zen Buddhism typical happy ending that promises ‘balance’ and ‘enlightenment’ but instead their stories coincide with Lacanian insights and describes the Chinese American experience as being more pessimistic, complex and less resolved. As the families in the novels eat and feed each other, they try to strive for balance but never quite reach their destination and are left unsatisfied. This study will then look at how women are depicted as Hungry Ghost through food imagery and dialogue in the selected novels. Keywords: women, representation, hungry ghost 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1THE THEORY OF LACAN One of the most glaring images found in Chinese literature is the representation of food and the role of the Hungry Ghost. According to Comiskey (1995), although the art of storytelling is a universal activity, much of its forms and contents depend on its cultural and historical contexts. Jacques Lacan insights can be applied in this study to further understand the depiction of food in the selected stories. -

To Read a PDF Version of This Media Release, Click Here

MEDIA RELEASE 29 July 2020 The past isn’t done with us yet… Catherine Văn-Davies leads the ensemble cast of new Australian drama series Hungry Ghosts Four-night special event on SBS Monday 24 August – Thursday 27 August at 9:30pm • INTERVIEWS AVAILABLE • IMAGES AND SCREENERS: HERE • FIRST LOOK TRAILER: HERE Chilling, captivating and utterly compelling, Hungry Ghosts follows four families that find themselves haunted by ghosts from the past. Filmed and set in Melbourne during the month of the Hungry Ghost Festival, when the Vietnamese community venerate their dead, this four-part drama series event from Matchbox Pictures premieres over four consecutive nights, Monday 24 August – Thursday 27 August at 9:30pm on SBS. When a tomb in Vietnam is accidentally opened on the eve of the Hungry Ghost Festival, a vengeful spirit is unleashed, bringing the dead with him. As these spirits wreak havoc across the Vietnamese-Australian community in Melbourne, reclaiming lost loves and exacting revenge, young woman May Le (Văn-Davies) must rediscover her true heritage and accept her destiny to help bring balance to a community still traumatised by war. Hungry Ghosts reflects the extraordinary lived and spiritual stories of the Vietnamese community and explores the inherent trauma passed down from one generation to the next, and how notions of displacement impact human identity – long after the events themselves. With one of the most diverse casts featured in an Australian drama series, Hungry Ghosts comprises more than 30 Asian-Australian actors and 325 -

Umithesis Lye Feedingghosts.Pdf

UMI Number: 3351397 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ______________________________________________________________ UMI Microform 3351397 Copyright 2009 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. _______________________________________________________________ ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS vi INTRODUCTION The Yuqie yankou – Present and Past, Imagined and Performed 1 The Performed Yuqie yankou Rite 4 The Historical and Contemporary Contexts of the Yuqie yankou 7 The Yuqie yankou at Puti Cloister, Malaysia 11 Controlling the Present, Negotiating the Future 16 Textual and Ethnographical Research 19 Layout of Dissertation and Chapter Synopses 26 CHAPTER ONE Theory and Practice, Impressions and Realities 37 Literature Review: Contemporary Scholarly Treatments of the Yuqie yankou Rite 39 Western Impressions, Asian Realities 61 CHAPTER TWO Material Yuqie yankou – Its Cast, Vocals, Instrumentation -

Modalities of Doing Religion and Ritual Polytropy: Evaluating the Religious

This article was downloaded by: [University of Cambridge] On: 12 February 2012, At: 13:02 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Religion Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rrel20 Modalities of doing religion and ritual polytropy: evaluating the religious market model from the perspective of Chinese religious history Adam Yuet Chau a a Department of East Asian Studies, Faculty of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, University of Cambridge, Sidgwick Avenue, Cambridge, CB3 9DA, United Kingdom Available online: 22 Dec 2011 To cite this article: Adam Yuet Chau (2011): Modalities of doing religion and ritual polytropy: evaluating the religious market model from the perspective of Chinese religious history, Religion, 41:4, 547-568 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0048721X.2011.624691 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and- conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

Dead Season1

158 Dead Season1 Caroline Sy HAU Professor, Center for Southeast Asian Studies Kyoto University In Kyoto, the Obon festival in honor of the spirits of ancestors falls around the middle of August. The day of the festival varies according to region and the type of calendar (solar or lunar) used. The Kanto region, including Tokyo, observes Obon in mid-July, while northern Kanto, Chugoku, Shikoku, and Okinawa celebrate their Old Bon (Kyu Bon) on the 15th day of the seventh month of the lunar calendar. For most Japanese, though, August, shimmering Nilotic August, is dead season. Children have their school break, Parliament is not in session, and as many who can afford it go abroad. Because Kyoto sits in a valley, daytime temperature can run up to the mid- and even upper 30s. Obon is not a public holiday, but people often take leave to return to their ancestral hometowns to visit and clean the family burial grounds. The Bon Odori dance is based on the story of the monk Mokuren, who on Buddha’s advice was able to ease the suffering of his dead mother and who was said to have danced for joy at her release. The festival culminates in paper lanterns being floated across rivers and in dazzling displays of fireworks. An added attraction in Kyoto is the Daimonji festival held on August 16. Between 8:00 and 8:20 p.m., fires in the shape of the characters “great” (dai, ) and “wondrous dharma” (myo/ho ) and in the shapes of a boat and a torii gate are lit in succession on five mountains encircling the city. -

Commentary on Je Tsong-Kha-Pa's Lam Rim Chen Mo by Venerable

Commentary on Je Tsong-kha-pa’s Lam Rim Chen Mo By Venerable Jih-Chang English Commentary Book 4, ver 3.0 Chapter 5 The Meditation Session & Chapter 6 Refuting Misconceptions about Meditation Printed by BW Monastery, Singapore For use by students of the monastery only Purpose: This book (version 3) contains the translation of Master Jih-Chang’s commentary of the Lamrim Chapter 5 “The Meditation Session” and Chapter 6 “Refuting Misconceptions about Meditation”. It is for use by BW Monastery students only. It serves to facilitate students' understanding of the Lamrim as explained by Master Jih-Chang. Student Feedback: The translation of Master's commentary in this book is still a draft and will be improved. All students are welcome to provide your feedback to improve the translation. Kindly submit your feedback via the feedback form that is available in the BW Monastery web page, where this book can be downloaded from. References: Before each paragraph of the translated commentary, the following references are indicated to help students in learning the commentary: - Page number of the English Lamrim Book. An example of this is “Lamrim text book Vol 1, P93” - Track number of Master Jih-Chang’s audio recording. An example is “22B, 10.24” - Page and line number of the Chinese commentary book. An example of this is “Original Commentary Script Vol 3, P202, L12”. Translator’s Notes: Parts with red text are notes inserted by the Translation Team. Contents Chapter 5: The Meditation Session 3 ~ 188 Chapter 6: Refuting Misconceptions about 189 ~ 314 Meditation CHAPTER 5: THE MEDITATION SESSION 4 Lamrim Vol 1 Chapter 5 Chapter 5 Outline 2. -

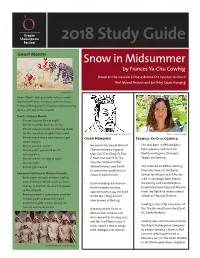

2018 Study Guide

2018 Study Guide Ghost Month Snow in Midsummer by Frances Ya-Chu Cowhig Based on the classical Chinese drama The Injustice to Dou Yi That Moved Heaven and Earth by Guan Hanqing Hungry Ghost Ghost Month falls generally in the seventh lunar month (late summer), with the Ghost Festival (Zhongyuan Festival) usually occurring on the 15th day of the month. Don’ts of Ghost Month: • Do not stay out late at night • Do not travel by land, air, or sea • Do not step on or kick an offering made for the ancestors or ghosts by a road Guan Hanqing (ca.1245-ca. 1322) Frances Ya-Chu Cowhig • Do not move into a new house or get Guan Hanqing Frances Ya-Chu Cowhig new furniture • Do not curse or swear • He wrote the zaju (a form of • She was born in Philadelphia, • Do not place your child on the Chinese drama or opera) Pennsylvania, and raised in offering altar play Gan Tian Dong Di Dou Northern Virginia, Okinawa, • Do not whistle or sing at night E Yuan, translated to The Taipei, and Beijing. • Do not swim Injustice to Dou Yi That • Do not get married Moved Heaven and Earth, • She received an MFA in Writing or sometimes published as from the James A. Michener Common Traditions in Chinese Funerals Snow in Midsummer. Center for Writers at UT Austin, • Burn paper versions of items such as a BA in Sociology from Brown cars, electronic devices such as iPads, • Guan Hanqing was born in University, and a certificate in money, or food for the dead to receive the thirteenth century, Ensemble-Based Physical Theatre in the afterlife. -

From-Hungry-Ghost-To-Being-Human-(Taking-Sajja-Beyond-Thamkrabok)

FROM HUNGRY GHOST TO BEING HUMAN: THE JOURNEY OF THE HERO Taking Sajja Beyond Wat Thamkrabok There is life without alcohol and other drugs - a life free from shame, free from blame and free from guilt – a life free from craving, free from aversion and free from confusion. Everyday Nibbana - every day. 2 Introduction The Realm of the Hungry Ghosts – the condition of unsatisfiable craving as experienced by alcoholics and drug addicts - is not a physical place but a mind-state; a state of being in the world. In fact, all of the ‘Realms of Becoming’ (often depicted as the Buddhist Wheel of Life) including the Heaven and Hell Realms and the Realm of Being Human are also mind- states; states of being in the world that we move through from moment to moment, often unconsciously, throughout each and every day. In Buddhism, all situations are temporary, transient and impermanent; even Heaven and Hell mind-states. Therefore, it is possible through our own conscious thoughts, words and actions to move away from the destructive suffering of addiction and compulsions – the living hell of the Hungry Ghost – to live in harmony and balance with the 10,000 sorrows and 10,000 joys of everyday life; embracing the ordinary and the mundane of just being human. The Realm of Being Human is where we cultivate self-discipline, make wise choices and take skilful actions. The Realm of Being Human is the world of opportunity, the world of possibilities, and the world of things as they really are. There are many paths leading away from the Realm of the Hungry Ghosts – the world of addictions and compulsions – to the Realm of Being Human and this little booklet tries to describe just one such path; the path of Sajja1 [pronounced : ‘Sat-cha’]. -

Title: Understanding Material Offerings in Hong Kong Folk Religion Author: Kagan Pittman Source: Prandium - the Journal of Historical Studies, Vol

Title: Understanding Material Offerings in Hong Kong Folk Religion Author: Kagan Pittman Source: Prandium - The Journal of Historical Studies, Vol. 8, No. 1 (Fall, 2019). Published by: The Department of Historical Studies, University of Toronto Mississauga Stable URL: http://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/prandium/article/view/16211/ 1 The following paper was written for the University of Toronto Mississauga’s RLG415: Advanced Topics in the Study of Religion.1 In this course we explored the topics of religion and death in Hong Kong. The trip to Hong Kong occurred during the 2019 Winter semester’s Reading Week. The final project could take any form the student wished, in consultation with the instructor, Ken Derry. The project was intended to explore a question posed by the student regarding religion and death in Hong Kong and answered using a combination of material from assigned readings in the class, our own experiences during the trip, and additional independent research. As someone with a history in professional writing, I chose for my final assignment to be in essay form. I selected material offerings as my subject given my history of interest with material religion, as in the expression of religion and religious ideas through physical mediums like art, and sacrificial as well as other sacred objects. --- Material offerings are an integral part to religious expression in Hong Kong’s Buddhist, Confucian and Taoist faith groups in varying degrees. Hong Kong’s folk religious practice, referred to as San Jiao (“Unity of the Three Teachings”) by Kwong Chunwah, Assistant Professor of Practical Theology at the Hong Kong Baptist Theological Seminary, combines key elements of these three faiths and so greatly influences the significance and use of material offerings, and explains much of what I have seen in Hong Kong over the course of a nine-day trip. -

Ghost-Movies in Southeast Asia and Beyond. Narratives, Cultural

DORISEA-Workshop Ghost-Movies in Southeast Asia and beyond. Narratives, cultural contexts, audiences October 3-6, 2012 University of Goettingen, Department of Social and Cultural Anthropology Convenor: Peter J. Braeunlein Abstracts Post-war Thai Cinema and the Supernatural: Style and Reception Context Mary Ainslie (Kuala Lumpur) Film studies of the last decade can be characterised by escalating scholarly interest in the diverse film forms of Far East Asian nations. In particular, such focus often turns to the ways in which the horror film can provide a culturally specific picture of a nation that offers insight into the internal conflicts and traumas faced by its citizens. Considering such research, the proposed paper will explore the lower-class ‘16mm era’ film form of 1950s and 60s Thailand, a series of mass-produced live-dubbed films that drew heavily upon the supernatural animist belief systems that organised Thai rural village life and deployed a film style appropriate to this context. Through textual analysis combined with anthropological and historical research, this essay will explore the ways in which films such as Mae-Nak-Prakanong (1959 dir. Rangsir Tasanapayak), Nguu-Phii (1966 dir. Rat Saet-Thaa-Phak-Dee), Phii-Saht-Sen-Haa (1969 dir. Pan-Kam) and Nang-Prai-Taa-Nii (1967 dir. Nakarin) deploy such discourses in relation to a dramatic wider context of social upheaval and the changes enacted upon rural lower-class viewers during this era, much of which was specifically connected to the post-war influx of American culture into Thailand. Finally it will indicate that the influence of this lower-class film style is still evident in the contemporary New Thai industry, illustrating that even in this global era of multiplex blockbusters such audiences and their beliefs and practices are still prominent and remain relevant within Thai society. -

From Preta to Hungry Ghost

Revisioning Buddhism © Piya Tan, 2015 From preta to hungry ghost1 Many of the early Buddhist teachings on death and afterdeath are better understood when we examine them against the prevailing belief-system of the brahmins in the Buddha’s time. Teach- ings such as those on the pretas (Pali peta) and the conduct of the living to the dead, which directly concern the laity, are Buddhist adaptations of brahminical beliefs and practices. The earliest Indian brahminical texts, the Vedas and Brāhmaṇas, rarely speculate on the fate of the dead, focusing almost exclusively on maintaining favourable living conditions in this world. Hence, there is little teaching here on the nature of the afterlife or the obligations of the living to the dead. It is only after the Buddha’s time, we see ancient funeral rituals that are still prac- tised in Indian society to this day. Up to the Buddha’s time, the prevalent brahminical conception of death centred around a class of beings known as pitara (pl), “the fathers, ancestors” (sg pitṛ). According to the Vedas, the newly dead has to take one of two paths, one leading to the realm of the gods (deva), the other to the Fathers. The latter is the prevalent one, that is, the path of the Fathers (pitṛ,yāna) to the world of the Fathers (pitṛ,loka; P petti,visaya). According to brahminical mythology, when the newly dead arrived in the world of the Fathers, king Yama or sometimes Agni (the fire god) gave him a new body. He was bathed in radiant light and given divine food. -

Hauntology Beyond the Cinema: the Technological Uncanny 66 Closings 78 5

Information manycinemas 03: dread, ghost, specter and possession ISSN 2192-9181 Impressum manycinemas editor(s): Michael Christopher, Helen Christopher contact: Matt. Kreuz Str. 10, 56626 Andernach [email protected] on web: www.manycinemas.org Copyright Copyright for articles published in this journal is retained by the authors, with first publication rights granted to the journal. The authors are free to re - publish their text elsewhere, but they should mention manycinemas as the first me- dia which has published their article. According to §51 Nr. 2 UrhG, (BGH, Urt. v. 20.12.2007, Aktz.: I ZR 42/05 – TV Total) German law, the quotation of pictures in academic works are allowed if text and screenshot are in connectivity and remain unchanged. Open Access manycinemas provides open access to its content on the principle that mak - ing research freely available to the public supports a greater global exchange of knowledge. Front: Screenshot The cabinet of Caligari Contents Editorial 4 Helen Staufer and Michael Christopher Magical thrilling spooky moments in cinema. An Introduction 6 Brenda S. Gardenour Left Behind. Child Ghosts, The Dreaded Past, and Reconciliation in Rinne, Dek Hor, and El Orfanato 10 Cen Cheng No Dread for Disasters. Aftershock and the Plasticity of Chinese Life 26 Swantje Buddensiek When the Shit Starts Flying: Literary ghosts in Michael Raeburn's film Triomf 40 Carmela Garritano Blood Money, Big Men and Zombies: Understanding Africa’s Occult Narratives in the Context of Neoliberal Capitalism 50 Carrie Clanton Hauntology Beyond the Cinema: The Technological Uncanny 66 Closings 78 5 Editorial Sorry Sorry Sorry! We apologize for the late publishing of our third issue.