Alphonse Mucha in Gilded Age America 1904-1921

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The American Public Art Museum: Formation of Its Prevailing Attitudes

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 1982 The American Public Art Museum: Formation of its Prevailing Attitudes Marilyn Mars Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Art Education Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/1302 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE AMERICAN PUBLIC ART MUSEUM: FORMATION OF ITS PREVAILING ATTITUDES by MARILYN MARS B.A., University of Florida, 1971 Submitted to the Faculty of the School of the Arts of Virginia Commonwealth University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of d~rts RICHMOND, VIRGINIA December, 1982 INTRODUCTION In less than one hundred years the American public art museum evolved from a well-intentioned concept into one of the twentieth century's most influential institutions. From 1870 to 1970 the institution adapted and eclipsed its European models with its didactic orientation and the drive of its founders. This striking development is due greatly to the ability of the museum to attract influential and decisive leaders who established its attitudes and governing pol.icies. The mark of its success is its ability to influence the way art is perceived and remembered--the museum affects art history. An institution is the people behind it: they determine its goals, develop its structure, chart its direction. -

The Effect of School Closure On

Social Status, the Patriarch and Assembly Balls, and the Transformation in Elite Identity in Gilded Age New York by Mei-En Lai B.A. (Hons.), University of British Columbia, 2005 Thesis Submitted In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Mei-En Lai 2013 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Spring 2013 Approval Name: Mei-En Lai Degree: Master of Arts (History) Title of Thesis: Social Status, the Patriarch and Assembly Balls, and the Transformation in Elite Identity in Gilded Age New York Examining Committee: Chair: Roxanne Panchasi Associate Professor Elise Chenier Senior Supervisor Associate Professor Jennifer Spear Supervisor Associate Professor Lara Campbell External Examiner Associate Professor, Department of Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies Simon Fraser University Date Defended/Approved: January 22, 2013 ii Partial Copyright Licence iii Abstract As exclusive upper-class balls that represented a fraction of elites during the Gilded Age, the Patriarch and Assembly Balls were sites where the Four Hundred engaged in practices of distinction for the purposes of maintaining their social statuses and of wresting social power from other fractions of elites. By looking at things such as the food, décor, and dancing at these balls, historians could arrive at an understanding of how the Four Hundred wanted to be perceived by others as well as the various types of capital these elites exhibited to assert their claim as the leaders of upper-class New York. In addition, in the process of advancing their claims as the rightful leaders of Society, the New York Four Hundred transformed elite identity as well as upper-class masculinity to include competitiveness and even fitness and vigorousness, traits that once applied more exclusively to white middle-class masculinity. -

Master Artist of Art Nouveau

Mucha MASTER ARTIST OF ART NOUVEAU October 14 - Novemeber 20, 2016 The Florida State University Museum of Fine Arts Design: Stephanie Antonijuan For tour information, contact Viki D. Thompson Wylder at (850) 645-4681 and [email protected]. All images and articles in this Teachers' Packet are for one-time educational use only. Table of Contents Letter to the Educator ................................................................................ 4 Common Core Standards .......................................................................... 5 Alphonse Mucha Biography ...................................................................... 6 Artsits and Movements that Inspired Alphonse Mucha ............................. 8 What is Art Nouveau? ................................................................................ 10 The Work of Alphonse Mucha ................................................................... 12 Works and Movements Inspired by Alphonse Mucha ...............................14 Lesson Plans .......................................................................................... Draw Your Own Art Nouveau Tattoo Design .................................... 16 No-Fire Art Nouveau Tiles ............................................................... 17 Art Nouveau and Advertising ........................................................... 18 Glossary .................................................................................................... 19 Bibliography ............................................................................................. -

Juraj Slăˇvik Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt6n39p6z0 No online items Register of the Juraj Slávik papers Finding aid prepared by Blanka Pasternak Hoover Institution Library and Archives © 2003, 2004 434 Galvez Mall Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305-6003 [email protected] URL: http://www.hoover.org/library-and-archives Register of the Juraj Slávik 76087 1 papers Title: Juraj Slávik papers Date (inclusive): 1918-1968 Collection Number: 76087 Contributing Institution: Hoover Institution Library and Archives Language of Material: Czech Physical Description: 54 manuscript boxes, 5 envelopes, 3 microfilm reels(23.5 Linear Feet) Abstract: Correspondence, speeches and writings, reports, dispatches, memoranda, telegrams, clippings, and photographs relating to Czechoslovak relations with Poland and the United States, political developments in Czechoslovakia, Czechoslovak emigration and émigrés, and anti-Communist movements in the United States. Creator: Slávik, Juraj, 1890-1969 Hoover Institution Library & Archives Access The collection is open for research; materials must be requested at least two business days in advance of intended use. Publication Rights For copyright status, please contact the Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Acquisition Information Acquired by the Hoover Institution Library & Archives in 1976. Preferred Citation [Identification of item], Juraj Slávik papers, [Box no., Folder no. or title], Hoover Institution Library & Archives. Alternative Form Available Also available on microfilm (51 reels). -

Four Mysterious Citizens of the United States That Served on The

Four Mysterious Citizens of the United States that Served On the International Olympic Com-mittee During the Period 1900-1917 Four Mysterious Citizens of the United States that Served On the International Olympic Com-mittee During the Period 1900-1917, Harvard University, William Milligan Sloane, Paris, Theodore Stanton, United States, America, American Olympic Committee, Olympic Games, Rutgers University, Pierre de Coubertin, International Olympic Committee, Karl Lennartz, Mr. Hyde, IOC member, Evert Jansen Wendell, Theodore Roosevelt, IOC members, Allison Vincent Armour, Olympic Research, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Baron Pierre de Coubertin, New York, Messieurs Stanton, Caspar Whitney, Cornell University, William Howard Taft, Evert Jansen, John Updike, North American, The International Olympic Committee One Hundred Years, See Wolf Lyberg, French Foreign Legion, See Barbara Tuchman, Barrett Wendell, father Jacob, Allison V. Armour, George Armour, President Coubertin, American University Union, American Red Cross, Coubertin, Phillips Brooks, A. V. Armour, New York City, Harvard, See Roosevelt, Swedish Olympic Organizing Committee, E. J. Wendell, List of IOC members, Doctor Sloane, John A. Lucas, the United States, Professor W. M. Sloane, Pennsylvania State University, Modern Olympic Games, Henry Brewster Stanton, James Hazen Hyde, Theodore Weld Stanton, Evert Jansen Wendell John A. Lucas, Professor Emeritus William M. Sloane, Theodore Roosevelt Papers, New York Herald, Professor Sloane, James Haren Hyde, Stanton, Keith Jones, RUDL, Allison -

The Art of Reading: American Publishing Posters of the 1890S

6. Artist unknown 15. Joseph J. Gould Jr. 19. Joseph Christian Leyendecker 35. Edward Penfield 39. Edward Penfield CHECKLIST The Delineator October, 1897 (American, ca. 1876–after 1932) (American, 1875–1951) (American, 1866–1925) (American, 1866–1925) All dimensions listed are for the sheet size; Color lithograph Lippincott’s November, 1896 Inland Printer January, 1897 Harper’s July, 1897 Harper’s March, 1899 9 9 height precedes width. Titles reflect the text 11 /16 × 16 /16 inches Color lithograph Color lithograph Color lithograph Color lithograph 9 1 1 1 3 3 as it appears on each poster. The majority Promised Gift of Daniel Bergsvik and 16 /16 × 13 /8 inches 22 /4 × 16 /4 inches 14 × 19 inches 15 /8 × 10 /4 inches of posters were printed using lithography, Donald Hastler Promised Gift of Daniel Bergsvik and Promised Gift of Daniel Bergsvik and Museum Purchase: Funds Provided by Promised Gift of Daniel Bergsvik and but many new printing processes debuted Donald Hastler Donald Hastler the Graphic Arts Council Donald Hastler 7. William H. Bradley during this decade. Because it is difficult or 2019.48.2 (American, 1868–1962) 16. Walter Conant Greenough 20. A. W. B. Lincoln 40. Edward Henry Potthast THE ART OF READING impossible to determine the precise method Harper’s Bazar Thanksgiving Number (American, active 1890s) (American, active 1890s) 36. Edward Penfield (American, 1857–1927) of production in the absence of contemporary 1895, 1895 A Knight of the Nets, 1896 Dead Man’s Court, 1895 (American, 1866–1925) The Century, July, 1896 documentation, -

Australian & International Posters

Australian & International Posters Collectors’ List No. 200, 2020 e-catalogue Josef Lebovic Gallery 103a Anzac Parade (cnr Duke St) Kensington (Sydney) NSW p: (02) 9663 4848 e: [email protected] w: joseflebovicgallery.com CL200-1| |Paris 1867 [Inter JOSEF LEBOVIC GALLERY national Expo si tion],| 1867.| Celebrating 43 Years • Established 1977 Wood engra v ing, artist’s name Member: AA&ADA • A&NZAAB • IVPDA (USA) • AIPAD (USA) • IFPDA (USA) “Ch. Fich ot” and engra ver “M. Jackson” in image low er Address: 103a Anzac Parade, Kensington (Sydney), NSW portion, 42.5 x 120cm. Re- Postal: PO Box 93, Kensington NSW 2033, Australia paired miss ing por tions, tears Phone: +61 2 9663 4848 • Mobile: 0411 755 887 • ABN 15 800 737 094 and creases. Linen-backed.| Email: [email protected] • Website: joseflebovicgallery.com $1350| Text continues “Supplement to the |Illustrated London News,| July 6, 1867.” The International Exposition Hours: by appointment or by chance Wednesday to Saturday, 1 to 5pm. of 1867 was held in Paris from 1 April to 3 November; it was the second world’s fair, with the first being the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London. Forty-two (42) countries and 52,200 businesses were represented at the fair, which covered 68.7 hectares, and had 15,000,000 visitors. Ref: Wiki. COLLECTORS’ LIST No. 200, 2020 CL200-2| Alfred Choubrac (French, 1853–1902).| Jane Nancy,| c1890s.| Colour lithograph, signed in image centre Australian & International Posters right, 80.1 x 62.2cm. Repaired missing portions, tears and creases. Linen-backed.| $1650| Text continues “(Ateliers Choubrac. -

Voices from the Field

Voices from the Field Voices from the Field Prohibition, war bonds, the formation of social security—the National Association of Insurance and Financial Advisors has seen it all. In August 1989, the National Association of Life Underwriters—later to be renamed NAIFA— published Voices from the Field, a seminal work chronicling the history of the insurance industry and the association. This book was the result of four years of research and writing by former Advisor Today senior editor George Norris. Voices from the Field is an engaging look at the lives and events that shaped our dynamic industry. The book remains a lasting tribute to everyone who has worked to make NAIFA what it is today, but particularly to Norris, who dedicated 21 years to the association. *** “Historians have, perhaps, been too preoccupied with mortality tables and the founding dates of companies to consider the astonishing influence that selling method, or the lack of it, has had upon the development of life insurance in every age.” —J. Owen Stalson, Marketing Life Insurance: Its History in America This book is dedicated to the hundreds of thousands of unnamed and often unsung, life underwriters who, over the past 100 years, have labored to provide security and financial independence to millions of their fellow Americans. Foreword by Alan Press, 1988-1989 NALU President Preface by Jack E. Bobo, 1989 NALU Executive Vice President Introduction Acknowledgements Chapter 1 Laying the Foundation—A Meeting at the Parker House Leading Figures—Ransom, Carpenter, Blodgett and -

John Quinn, Art Advocate

John Quinn, Art Advocate Introduction Today I’m going to talk briefly about John Quinn (fig. 1), a New York lawyer who, in his spare time and with income derived from a highly-successful law practice, became “the twentieth century’s most important patron of living literature and art.”1 Nicknamed “The Noble Buyer” for his solicitude for artists as much as for the depth of his pocketbook, Quinn would amass an unsurpassed collection of nineteenth- and twentieth-century American and European art. At its zenith, the collection con- tained more than 2,500 works of art, including works by Con- stantin Brancusi, Paul Cézanne, André Derain, Marcel Du- champ, Raymond Duchamp-Villon, Henri Gaudier-Brzeska, Paul Gaugin, Juan Gris, Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Georges Rouault, Henri Rousseau, Georges Seurat, and Vincent van Gogh.2 More than a collector, Quinn represented artists and art associa- tions in all types of legal matters. The most far-reaching of these en- gagements was Quinn’s successful fight for repeal of a tariff on im- 1 ALINE B. SAARINEN, THE PROUD POSSESSORS: THE LIVES, TIMES AND TASTES OF SOME ADVENTUROUS AMERICAN ART COLLECTORS 206 (1958) [hereinafter PROUD POSSESSORS]. 2 Avis Berman, “Creating a New Epoch”: American Collectors and Dealers and the Armory Show [hereinafter American Collectors], in THE ARMORY SHOW AT 100: MODERNISM AND REVOLUTION 413, 415 (Marilyn Satin Kushner & Kimberly Orcutt eds., 2013) [hereinafter KUSHNER & ORCUTT, ARMORY SHOW] (footnote omitted). ported contemporary art3 – an accomplishment that resulted in him being elected an Honorary Fellow for Life by the Metropolitan Mu- seum of Art.4 This work, like much Quinn did for the arts, was un- dertaken pro bono.5 Quinn was also instrumental in organizing two groundbreaking art exhibitions: the May 1921 Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibition of “Impressionist and Post-Impressionist Paintings” (that museum’s first exhibition of modern art),6 and the landmark 1913 “International Exhibition of Modern Art”7 – otherwise known as the Armory Show. -

Objectified Through an Implied Male Gaze

Lehigh Preserve Institutional Repository “Dear Louie:” Louisine Waldron Elder Havemeyer, Impressionist Art Collector and Woman Suffrage Activist Ganus, Linda Carol 2017 Find more at https://preserve.lib.lehigh.edu/ This document is brought to you for free and open access by Lehigh Preserve. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of Lehigh Preserve. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Dear Louie:” Louisine Waldron Elder Havemeyer, Impressionist Art Collector and Woman Suffrage Activist by Linda C. Ganus A Thesis Presented to the Graduate and Research Committee of Lehigh University in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts In the Department of History Lehigh University August 4, 2017 © 2017 Copyright Linda C. Ganus ii Thesis is accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of (Arts/Sciences) in (Department/Program). “Dear Louie:” Louisine Waldron Elder Havemeyer, Impressionist Art Collector and Woman Suffrage Activist Linda Ganus Date Approved Dr. John Pettegrew Dr. Roger Simon iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would first like to thank my thesis advisor, Dr. John Pettegrew, Chair of the History Department at Lehigh University. In addition to being a formidable researcher and scholar, Prof. Pettegrew is also an unusually empathetic teacher and mentor; tireless, positive, encouraging, and always challenging his students to strive for the next level of excellence in their critical thinking and writing. The seeds for this project were sown in Prof. Pettegrew’s Intellectual U.S. History class, one of the most influential classes I have had the pleasure to take at Lehigh. I am also extremely grateful to Dr. -

Whether Contemplating a Dabble in the World of Art Investment Or A

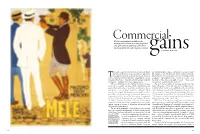

CommercialWhether contemplating a dabble in the world of art investment or a stultifying blank wall, gems from the golden age of Art Deco menswear advertising offer a perfect solution. gainsby christian chensvold here comes a point in the life of any instinctively elegant get from lithography is pure, solid colour,” says poster dealer man where he must face the question of how to appoint his Jim Lapides of the International Poster Gallery in Boston, living quarters. And, those for whom sartorial obsession Massachusetts. “It’s not dots like in the offset printing used for Tis all-consuming will likely find inner tranquillity in covering newspapers. Lithography provides a richness of texture, even the walls of their home — their haven from the vulgar world that the texture of the stone, and depth of colour — there aren’t lies beyond — with depictions of masculine panache. many artisans around today who can do it.” If that sounds like you, look no further than these European The most famous maker of menswear posters was the posters from a golden age when stylish advertising images Swiss clothing firm of PKZ, which stood for Paul Kehl, Zurich. greeted the boulevardier as he strolled, boutonniere abloom Dazzling in their variety and creativity, from the 1920s to the and malacca cane in hand, along the continent’s urban 1960s, they made some of the finest examples of the genre. One avenues. The original Pop Art posters — viewable cost-free of its masterpieces, a single minimalist button depicted by artist on trolleys, in train stations and on street-side kiosks — rose Otto Baumberger, hangs in New York’s Museum of Modern Art. -

His Exhibition Features More Than Two Hundred Pieces of Jewelry Created Between 1880 and Around 1930. During This Vibrant Period

his exhibition features more than two hundred pieces of jewelry created between 1880 and around 1930. During this vibrant period, jewelry makers in the world’s centers of design created audacious new styles in response to growing industrialization and the changing Trole of women in society. Their “alternative” designs—boldly artistic, exquisitely detailed, hand wrought, and inspired by nature—became known as art jewelry. Maker & Muse explores five different regions of art jewelry design and fabrication: • Arts and Crafts in Britain • Art Nouveau in France • Jugendstil and Wiener Werkstätte in Germany and Austria • Louis Comfort Tiffany in New York • American Arts and Crafts in Chicago Examples by both men and women are displayed together to highlight commonalities while illustrating each maker’s distinctive approach. In regions where few women were present in the workshop, they remained unquestionably present in the mind of the designer. For not only were these pieces intended to accent the fashionable clothing and natural beauty of the wearer, women were also often represented within the work itself. Drawn from the extensive jewelry holdings of collector Richard H. Driehaus and other prominent public and private collections, this exhibition celebrates the beauty, craftsmanship and innovation of art jewelry. WHAT’S IN A LABEL? As you walk through the exhibition Maker and Muse: Women and Early Guest Labels were written by: Twentieth Century Art Jewelry you’ll Caito Amorose notice a number of blue labels hanging Jon Anderson from the cases. We’ve supplemented Jennifer Baron our typical museum labels for this Keith Belles exhibition by adding labels written by Nisha Blackwell local makers, social historians, and Melissa Frost fashion experts.