Mars' Craters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PDF Files Are Openly Distributed for the Educational Purpose Only. Reuse And/Or Modifications of Figures and Tables in the PDF Files Are Not Allowed

PDF files are openly distributed for the educational purpose only. Reuse and/or modifications of figures and tables in the PDF files are not allowed. 3. Ancient landforms: Understanding the early Mars environment 3.1 Erosional landforms 3.1.1 Outflow channels 3.1.2 Valley networks 3.1.3 Erosional processes on early Mars 3.2 Standing bodies of water 3.2.1 Ocean and shorelines 3.2.2 Crater lakes and deltas 3.2.3 Layered deposits 3.3 Composition of sediments: from geomorphology to geology 3.3.1 MER rover discoveries 3.3.2 Exobiological issues 3.1.1 Outflow channels Length: 100 to 1000 km Width: 1 to 30 km Low gradient (<0.1) Anastomosing patterns, braided systems Teardrop-shaped islands Discharge rate :107 –109 m3 s-1 (Baker, 1981; Komar, 1986) 20 km Mangala valles 500 m Ares Valles Terrestrial floods: high discharge (here due to a storm) The Channeled Scabland analogy (Baker and Milton, 1974) ------- 40 km Columbia Basin (eastern Washington, USA) A glacial dam releases the subglacial lake Discharges of 2 x107 m3 s-1 Geographic distribution: Correlation with volcanic regions Role of geothermal activity Outflow channels (red) and valley networks (yellow) Elysium Mons Tharsis bulge From Carr, 1979 Relationship between chaotic terrains and outflow channels Chryse Planitia Kasei dfg Valles +Viking 1 + Pathfinder Ares Vallis Disruption of the permafrost at the source? Valles Marineris MOLA data Altitude (m) A recent outflow channel: Athabasca Vallis Outflow from fractures Very young: ~10 million years ago (Burr et al, 2002) (Berman and Hartmann, 2003) 6 km Origin of outflow channels 1 -Ground water under pressure confined within the permafrost (M. -

Drainage Network Development in the Keanakāko'i

JOURNAL OF GEOPHYSICAL RESEARCH, VOL. 117, E08009, doi:10.1029/2012JE004074, 2012 Drainage network development in the Keanakāko‘i tephra, Kīlauea Volcano, Hawai‘i: Implications for fluvial erosion and valley network formation on early Mars Robert A. Craddock,1 Alan D. Howard,2 Rossman P. Irwin III,1 Stephen Tooth,3 Rebecca M. E. Williams,4 and Pao-Shin Chu5 Received 1 March 2012; revised 11 June 2012; accepted 4 July 2012; published 22 August 2012. [1] A number of studies have attempted to characterize Martian valley and channel networks. To date, however, little attention has been paid to the role of lithology, which could influence the rate of incision, morphology, and hydrology as well as the characteristics of transported materials. Here, we present an analysis of the physical and hydrologic characteristics of drainage networks (gullies and channels) that have incised the Keanakāko‘i tephra, a basaltic pyroclastic deposit that occurs mainly in the summit area of Kīlauea Volcano and in the adjoining Ka‘ū Desert, Hawai‘i. The Keanakāko‘i tephra is up to 10 m meters thick and largely devoid of vegetation, making it a good analog for the Martian surface. Although the scales are different, the Keanakāko‘i drainage networks suggest that several typical morphologic characteristics of Martian valley networks may be controlled by lithology in combination with ephemeral flood characteristics. Many gully headwalls and knickpoints within the drainage networks are amphitheater shaped, which results from strong-over-weak stratigraphy. Beds of fine ash, commonly bearing accretionary lapilli (pisolites), are more resistant to erosion than the interbedded, coarser weakly consolidated and friable tephra layers. -

Groundwater Seepage Landscapes from Distant and Local Sources in Experiments and on Mars

Earth Surf. Dynam., 3, 389–408, 2015 www.earth-surf-dynam.net/3/389/2015/ doi:10.5194/esurf-3-389-2015 © Author(s) 2015. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Groundwater seepage landscapes from distant and local sources in experiments and on Mars W. A. Marra1, S. J. McLelland2, D. R. Parsons2, B. J. Murphy2, E. Hauber3, and M. G. Kleinhans1 1Faculty of Geosciences, Universiteit Utrecht, Heidelberglaan 2, 3584 CS, Utrecht, the Netherlands 2Department of Geography, Environment and Earth Sciences, University of Hull, Cottingham Road, Hull, HU6 7RX, UK 3Deutsches Zentrum für Luft- und Raumfahrt (DLR), Institut für Planetenforschung, Rutherfordstraße 2, 12489 Berlin, Germany Correspondence to: W. A. Marra ([email protected]) Received: 4 February 2015 – Published in Earth Surf. Dynam. Discuss.: 19 February 2015 Revised: 18 June 2015 – Accepted: 3 July 2015 – Published: 4 August 2015 Abstract. Valleys with theater-shaped heads can form due to the seepage of groundwater and as a result of knickpoint (waterfall) erosion generated by overland flow. This ambiguity in the mechanism of formation ham- pers the interpretation of such valleys on Mars, particularly since there is limited knowledge of material prop- erties. Moreover, the hydrological implications of a groundwater or surface water origin are important for our understanding of the evolution of surface features on Mars, and a quantification of valley morphologies at the landscape scale may provide diagnostic insights on the formative hydrological conditions. However, flow pat- terns and the resulting landscapes produced by different sources of groundwater are poorly understood. We aim to improve the understanding of the formation of entire valley landscapes through seepage processes from dif- ferent groundwater sources that will provide a framework of landscape metrics for the interpretation of such systems. -

Orbital Evidence for More Widespread Carbonate- 10.1002/2015JE004972 Bearing Rocks on Mars Key Point: James J

PUBLICATIONS Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets RESEARCH ARTICLE Orbital evidence for more widespread carbonate- 10.1002/2015JE004972 bearing rocks on Mars Key Point: James J. Wray1, Scott L. Murchie2, Janice L. Bishop3, Bethany L. Ehlmann4, Ralph E. Milliken5, • Carbonates coexist with phyllosili- 1 2 6 cates in exhumed Noachian rocks in Mary Beth Wilhelm , Kimberly D. Seelos , and Matthew Chojnacki several regions of Mars 1School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, Georgia, USA, 2The Johns Hopkins University/Applied Physics Laboratory, Laurel, Maryland, USA, 3SETI Institute, Mountain View, California, USA, 4Division of Geological and Planetary Sciences, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, California, USA, 5Department of Geological Sciences, Brown Correspondence to: University, Providence, Rhode Island, USA, 6Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona, USA J. J. Wray, [email protected] Abstract Carbonates are key minerals for understanding ancient Martian environments because they Citation: are indicators of potentially habitable, neutral-to-alkaline water and may be an important reservoir for Wray, J. J., S. L. Murchie, J. L. Bishop, paleoatmospheric CO2. Previous remote sensing studies have identified mostly Mg-rich carbonates, both in B. L. Ehlmann, R. E. Milliken, M. B. Wilhelm, Martian dust and in a Late Noachian rock unit circumferential to the Isidis basin. Here we report evidence for older K. D. Seelos, and M. Chojnacki (2016), Orbital evidence for more widespread Fe- and/or Ca-rich carbonates exposed from the subsurface by impact craters and troughs. These carbonates carbonate-bearing rocks on Mars, are found in and around the Huygens basin northwest of Hellas, in western Noachis Terra between the Argyre – J. -

Bio-Preservation Potential of Sediment in Eberswalde Crater, Mars

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Graduate School Collection WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship Fall 2020 Bio-preservation Potential of Sediment in Eberswalde crater, Mars Cory Hughes Western Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet Part of the Geology Commons Recommended Citation Hughes, Cory, "Bio-preservation Potential of Sediment in Eberswalde crater, Mars" (2020). WWU Graduate School Collection. 992. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet/992 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Graduate School Collection by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bio-preservation Potential of Sediment in Eberswalde crater, Mars By Cory M. Hughes Accepted in Partial Completion of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science ADVISORY COMMITTEE Dr. Melissa Rice, Chair Dr. Charles Barnhart Dr. Brady Foreman Dr. Allison Pfeiffer GRADUATE SCHOOL David L. Patrick, Dean Master’s Thesis In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Western Washington University, I grant to Western Washington University the non-exclusive royalty-free right to archive, reproduce, distribute, and display the thesis in any and all forms, including electronic format, via any digital library mechanisms maintained by WWU. I represent and warrant this is my original work, and does not infringe or violate any rights of others. I warrant that I have obtained written permissions from the owner of any third party copyrighted material included in these files. -

PLANETARIAN Journal of the International Planetarium Society Vol

PLANETARIAN Journal of the International Planetarium Society Vol. 26, No.3, September 1997 Articles 5 Projections from Gallatin .................................................... Gary Likert 10 How Thinking Goes Wrong ....................................... Michael Shermer 17 Astronomy Link - A Beginning ........................................ Jim Manning 21 14th International Planetarium Conference ................................ IPS'98 Features 26 Opening the Dome .............................................................. Jon U. Bell 29 Planetarium Memories .........., .................................. Kenneth E. Perkins 31 Planetechnica: Shoestring Wire Management ......... Richard McColman 34 Forum ................................................................................. Steve Tidey 39 Book Reviews .................................................................. April S. Whitt 45 Mobile News Network ...................................................... Sue Reynolds 47 ',X/hat's New ...................................................................... Jim Manning 51 Gibbous Gazette ......................................................... Christine Shupla 53 Regional Roundup ............................................................ Lars Broman 58 President's Message ....................................................... Thomas Kraupe 62 Jane's Corner .................................................................... Jane Hastings " l1,c ZKPJ ;'\' jalltastic ... It IJrojec/x Ih e 11/ 0 0 1/ phases wilh (l -

Nirgal Vallis: Evidence for Extensive Sapping

Lunar and Planetary Science XXXIII (2002) 1579.pdf Nirgal Vallis: Evidence for Extensive Sapping. R. Jaumann and D. Reiss, DLR, German Aerospace Center, Institute of Space Sensor Technology and Planetary Exploration, D-12489 Berlin, Rutherfordstr. 2, Germany, [email protected] Abstract: The topographic information provided Nirgal Vallis is located in the southern highlands by the Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter has been used in at about 29°S ranging from 47°W to 38°W and span- combination with Viking and Mars Orbiter Camera ning a height difference of about 1000 m. The dip an- imagery to estimate the three-dimensional structure of gle of the surface dissected by the valley, is extremely low (0.01°). The longitudinal profile of the valley is the Nirgal Vallis drainage system in order to constrain linear (Fig. 2). The width to depth ratio ranges from 9 the formation process. The analysis of morphometric upstream to 8 downstream (Fig. 3) which is nearly and topologic network parameters indicates sapping as constant compared to run-off values on earth (ranging the major valley network forming process. from 2 to > 40). The heads of all tributaries are steep Introduction: Since the discovery of valley net- walled amphitheater-like boxes of well-developed al- works in Mariner 9 images the relative roles of surface coves [see also 11]. run-off versus groundwater processes in valley net- work formation have been debated [e.g 1,2,3]. Due to features such as U-shaped cross sections, alcove-like terminations of tributaries and the structural control of the networks, most of the highland valleys are attrib- uted to an origin by groundwater sapping. -

Mars-Match-Slides.Pdf

MA RS Clouds A B Clouds A Eastern 2/3 of the U.S. Clouds Clouds on Mars are made of _____ . A. water B. carbon dioxide C. water and carbon dioxide Clouds on Mars are made of _____ . A. water B. carbon dioxide C. water and carbon dioxide Ice cap, Antarctica A B Ice cap, Antarctica Sout A h Nort B h Ice cap, Antarctica The northern ice cap on Mars consists of frozen _____ . A. water B. carbon dioxide C. water and carbon dioxide The northern ice cap on Mars consists of frozen _____ . A. water B. carbon dioxide C. water and carbon dioxide Dust storm A B Dust storm A Sahara dust storm Polar dust storm True or False? Dust storms on Mars can cover the entire planet. True! Dust storms on Mars can cover the entire planet. 2018 Dust Devil A B Dust Devil A Seen from the ground by the Opportunity rover B Dust Devil Seen from above by the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter Barchan dunes, Mawrth Valles A B Barchan dunes, Mawrth Valles A Sahara Desert Barchan dunes, Mawrth Valles Aorounga impact crater, Chad A B Aorounga impact crater, Chad B Lowell Crater Aorounga impact crater, Chad River Delta, Jezero Crater A B River Delta, Jezero Crater B Horton River Delta, Canada River Delta, Jezero Crater What is the name of the rover that will land in Jezero crater in 2021? A. Perseverance B. Curiosity C. Spirit What is the name of the rover that will land in Jezero crater in 2021? A. Perseverance B. -

In Pdf Format

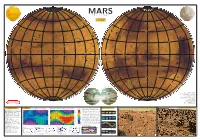

lós 1877 Mik 88 ge N 18 e N i h 80° 80° 80° ll T 80° re ly a o ndae ma p k Pl m os U has ia n anum Boreu bal e C h o A al m re u c K e o re S O a B Bo l y m p i a U n d Planum Es co e ria a l H y n d s p e U 60° e 60° 60° r b o r e a e 60° l l o C MARS · Korolev a i PHOTOMAP d n a c S Lomono a sov i T a t n M 1:320 000 000 i t V s a Per V s n a s l i l epe a s l i t i t a s B o r e a R u 1 cm = 320 km lkin t i t a s B o r e a a A a A l v s l i F e c b a P u o ss i North a s North s Fo d V s a a F s i e i c a a t ssa l vi o l eo Fo i p l ko R e e r e a o an u s a p t il b s em Stokes M ic s T M T P l Kunowski U 40° on a a 40° 40° a n T 40° e n i O Va a t i a LY VI 19 ll ic KI 76 es a As N M curi N G– ra ras- s Planum Acidalia Colles ier 2 + te . -

Constraints on Overland Fluid Transport Through Martian Valley Networks. M

Lunar and Planetary Science XXXI 1189.pdf CONSTRAINTS ON OVERLAND FLUID TRANSPORT THROUGH MARTIAN VALLEY NETWORKS. M. C. Malin and K. S. Edgett, Malin Space Science Systems, Box 910148, San Diego, CA 92191-0148, USA. Introduction: Since their discovery in Mariner 9 networks. images [1,2], Òrunoff channelsÓ [3], or more properly, Flow Integration: Arguably the best example Òmartian valley networksÓ [4,5] have been almost uni- found on Mars of an arborescent network are the War- versally cited as the best evidence that Mars once rego Valles. Earlier Viking data, and now MGS im- maintained an environment capable of supporting the ages, raise serious questions concerning the interpreta- flow of liquid water across its surface. Unlike Òoutflow tion of these valleys as surficial drainage. First, the channels,Ó that appear to indicate brief, catastrophic valleys are not Òthrough-going,Ó but rather consist of releases of fluid from very localized sources, valley transecting, elongate, occasionally isolated depres- networks often display arborescent patterns, sinuosity sions. Second, mass movements appear to have played and occasionally meandering patterns that imply proc- a role in both extending and widening the valleys. esses of overland flow: drainage basin development Third, the valley walls are extremely subdued, reflect- and sustained surficial transport of fluid. As part of the ing either mantling or an origin by collapse. These on-going Mars Global Surveyor (MGS) Mars Orbiter attributes suggest that collapse may have played the Camera (MOC) imaging activities, many observations dominant role in formation of valley networks of valley networks have been planned and executed; the Discussion: Groundwater follows topographic gra- results of some of these observations have been previ- dients nearly as effectively as surface water. -

The Surface of Mars Michael H. Carr Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-87201-0 - The Surface of Mars Michael H. Carr Index More information Index Accretion 277 Areocentric longitude Sun 2, 3 Acheron Fossae 167 Ares Vallis 114, 116, 117, 231 Acid fogs 237 Argyre 5, 27, 159, 160, 181 Acidalia Planitia 116 floor elevation 158 part of low around Tharsis 85 floor Hesperian in age 158 Admittance 84 lake 156–8 African Rift Valleys 95 Arsia Mons 46–9, 188 Ages absolute 15, 23 summit caldera 46 Ages, relative, by remote sensing 14, 23 Dikes 47 Alases 176 magma supply rate 51 Alba Patera 2, 17, 48, 54–7, 92, 132, 136 Arsinoes Chaos 115, 117 low slopes 54 Ascreus Mons 46, 49, 51 flank fractures 54 summit caldera 49 fracture ring 54 flank vents 49 dikes 55 rounded terraces 50 pit craters 55, 56, 88 Asteroids 24 sheet flows 55, 56 Astronomical unit 1, 2 Tube-fed flows 55, 56 Athabasca Vallis 59, 65, 122, 125, 126 lava ridges 55 Atlantis Chaos 151 dilatational faults 55 Atmosphere collapse 262 channels 56, 57 Atmosphere, chemical composition 17 pyroclastic deposits 56 circulation 8 graben 56, 84, 86 convective boundary layer 9 profile 54 CO2 retention 260 Albedo 1, 9, 193 early Mars 263, 271 Albor Tholus 60 eddies 8 ALH84001 20, 21, 78, 267, 273–4, 277 isotopic composition 17 Alpha Particle X-ray Spectrometer 232 mass 16 Alpha Proton-ray Spectrometer 231 meridional flow 1 Alpheus Colles 160 pressure variations and range 5, 16 AlQahira 122 temperatures 6–8 Amazonian 277 scale height 5, 16 Amazonis Planitia 45, 64, 161, 195 water content 11 flows 66, 68 column water abundance 174 low -

Bedform Migration on Mars: Current Results and Future Plans

Aeolian Research xxx (2013) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Aeolian Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/aeolia Review Article Bedform migration on Mars: Current results and future plans ⇑ Nathan Bridges a, , Paul Geissler b, Simone Silvestro c, Maria Banks d a Johns Hopkins University, Applied Physics Laboratory, 200-W230, 11100 Johns Hopkins Road, Laurel, MD 20723, USA b US Geological Survey, Astrogeology Science Center, 2255 N. Gemini Drive, Flagstaff, AZ 86001-1698, USA c SETI Institute, 189 Bernardo Ave., Suite 100, Mountain View, CA 94043, USA d Center for Earth and Planetary Studies, Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, Washington, DC 20013-7012, USA article info abstract Article history: With the advent of high resolution imaging, bedform motion can now be tracked on the Martian surface. Received 30 July 2012 HiRISE data, with a pixel scale as fine as 25 cm, shows displacements of sand patches, dunes, and ripples Revised 19 February 2013 up to several meters per Earth year, demonstrating that significant landscape modification occurs in the Accepted 19 February 2013 current environment. This seems to consistently occur in the north polar erg, with variable activity at Available online xxxx other latitudes. Volumetric dune and ripple changes indicate sand fluxes up to several cubic meters per meter per year, similar to that found in some dune fields on Earth. All ‘‘transverse aeolian ridges’’ Keywords: are immobile. There is no relationship between bedform activity and coarse-scale global circulation mod- Mars els, indicating that finer scale topography and wind gusts, combined with the predicted low impact Dunes Ripples threshold on Mars, are the primary drivers.