Shaw V. Lindheim

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jennifer Chovancek

JENNIFER CHOVANCEK ASSISTANT PRODUCTION COORDINATOR 1-95 Malvern Ave. Toronto On M4E 3E6 C.416-844-6780 [email protected] Assistant Production Workin’ Moms Television Series CBC Coordinator Producers: Catherine Reitman, Philip 07-11, 2016 Sternberg, Jonathan Walker PM: Anthony Pangalos PC: Michelle Kanyo Assistant Production The Stanley Dynamic II Television Sitcom YTV Coordinator Producers: Teza Lawrence, Michael 08, 2015 - 04, 2016 Souther, Ken Cuperus, Victoria Hirst PM: Maribeth Daley PC: Alison Waxman 2nd Unit Assistant Warrior TV Pilot NBC Production Producer: Marc David Alpert 03-04, 2015 Coordinator PM: Brian Campbell PC: Keitha Redmond Production The Stanley Dynamic Television Sitcom YTV Coordinator Producers: Teza Lawrence, Michael 05-12, 2014 Souther, Ken Cuperus, Victoria Hirst PM: Maribeth Daley Assistant Production The Stanley Dynamic Television Sitcom YTV Coordinator Producers: Teza Lawrence, Michael 02-05, 2014 Souther, Ken Cuperus, Victoria Hirst PM: Maribeth Daley PC: Alison Waxman Travel Coordinator The Best Laid Plans TV Mini Series CBC Producers: Brian Dennis, Phyllis Platt, 05-12, 2013 Peter Moss PM: Mary Pantelidis Assistant Production The F Word Feature Film No Trace Coordinator Producers: Jessie Shapira, Jeff Arkuss, 05-11, 2012 Camping David Gross, Hartley Gorenstein PM: Reggie Robb PC: Alison Waxman Assistant Production COPPER Television Series Cineflix/ BBC/ Coordinator Producers: Glen Salzman, Brad Van 12, 2011-03,2012 Shaw Arragon PM: Chris Danton PC: Nancy Jackson Assistant Production Sunshine Sketches -

Indie TV: Innovation in Series Development Aymar Jean Christian Northwestern Univeristy I Spent Five Years Interviewing Creators

Indie TV: Innovation in series development DRAFT Aymar Jean Christian Northwestern Univeristy I spent five years interviewing creators of American web series, or independent television online,1 speaking with 134 producers and executives making and releasing scripted series independent of traditional network investment. No two series or creators were ever alike. Some were sci-fi comedies created by Trekkers, others urban dramas by black women. Nevertheless nearly every creator differentiated their work and products from traditional television in some way. Strikingly, whenever I ask if any particular creator inspired them to develop their own show independently, I heard one response more than any other: Felicia Day. Indie TV creators revere Day for her innovation in production and distribution: she developed a hit franchise, The Guild, outside network development processes. The Guild, a sitcom about a diverse group of gamers who sit at computers all day to play an MMORPG in the style of World of Warcraft, ran for six seasons, from 2007 to 2013, and spawned a music video, DVDs, comic books, a companion book, as well as marshaled the passions of hundreds of thousands of fans. By the end of its run, The Guild had amassed over 330,000 subscribers on YouTube, though it could also be seen on other portals. In my work I have seen The Guild emerge as central to the online indie TV industry’s case for itself as antidote to what ails Hollywood. Day initially pitched to Christian, A.J. (forthcoming). Indie TV: Innovation in Series Development, in Media Independence: 1 working with freedom or working for free?. -

Substantial Similarity in Literary Infringement Cases: a Chart for Turbid Waters

UCLA UCLA Entertainment Law Review Title Substantial Similarity in Literary Infringement Cases: A Chart for Turbid Waters Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0m10v6t3 Journal UCLA Entertainment Law Review, 21(1) ISSN 1073-2896 Author Helfing, Robert F. Publication Date 2014 DOI 10.5070/LR8211027175 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Substantial Similarity in Literary Infringement Cases: A Chart for Turbid Waters Robert F. Helfing* As home to thatfictional piece of real estate known as Hollywood, the Ninth Circuit has dealt with the copyright law issue of substantial similarity more than any other jurisdiction,yet it has not developed useful principlesfor analyzing it. This article examines the history of the Ninth Circuit's two-step test for substantialsimilarity in literary in- fringement cases, showing how a quirk in the evolution of the test has created a confusing and ineffectual body of law on the subject. The ar- ticle argues that the courts have underestimated the complexity of the issue and have given too much credit to their own judgment, unaided by expert input. The absence of a genuine understandingof the issue has led courts to look for substantial similarity where it cannot be found: in the individual elements of literary works. The article pre- sents a proposed rule to re-direct the court's inquiryfrom the individ- ual elements of the work, where copyright protection cannot be found, to the artistic structure of the work, where it must be found if it exists at all. Robert F. Helfing is a senior partner and head of the Intellectual Property Department of Sedgwick LLP. -

College Admissions, Rigged for the Rich

$2.75 DESIGNATED AREASHIGHER©2019 WSCE D WEDNESDAY, MARCH 13,2019 latimes.com College admissions, riggedfor therich Scheme paid coaches, faked test scores to securespots forchildren of the wealthy By Joel Rubin, Hannah Fry, Richard Winton and MatthewOrmseth When it came to getting their daughtersintocollege, actress Lori Loughlinand fashion designer J. Mossimo Giannulli were taking no chances. The wealthy,glamorous couple were determined their girls would attend USC, ahighly competitive school that offers seats only CJ Gunther EPA/Shutterstock to afractionofthe thou- WILLIAM SINGER sands of students who apply pleaded guiltyTuesdayto eachyear. racketeering and other So they turned to William charges in the scheme. Singer and the “side door” the NewportBeach busi- nessman said he had built intoUSC and otherhighly The big sought afteruniversities. Half amillion dollars later — Allen J. Schaben Los Angeles Times $400,000ofitsent to Singer FOR MILLIONS OF CALIFORNIANS who live near thecoast, the threatofrising sea levels and storms is and $100,000 to an adminis- business very real. Last year,winter stormseroded Capistrano Beach in Dana Point, causing aboardwalk to collapse. trator in USC’s vaunted ath- leticprogram —the girls were enrolled at the school. of getting Despitehaving nevercom- peted in crew,both had been ‘Massive’damagemay givencoveted slots reserved NEWSOM for rowers who were ex- accepted pected to join the school’s team. “This is wonderful news!” Experts call for TO HALT be the norm by 2100 Loughlin emailed Singer af- terreceiving word that a reforms to levelthe spotfor her second daughter playing field in a DEATH had been secured. She add- thriving industrythat Rising seas and routine storms couldbemore ed ahigh-five emoji. -

2014 Television Pilot Production Report Provides Updated Insight Into L.A.’S Ongoing Loss of New Television Pilot Projects and Promising Series

Contact: Philip Sokoloski Danielle Walker VP, Integrated Communications Communications Coordinator (213) 977-8630 (213) 977-8635 [email protected] [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE New York Surpasses Los Angeles in Attracting New TV Drama Pilots Los Angeles’ Annual Pilot Production Share Slips to 44 Percent – A New Low LOS ANGELES – June 24, 2014 – FilmL.A., the not-for-profit film office serving the Greater Los Angeles Region, today announced the release of a new report prepared by its research division. The 2014 Television Pilot Production Report provides updated insight into L.A.’s ongoing loss of new television pilot projects and promising series. The 2013/2014 development cycle saw New York (with 24 drama projects retained) dethrone Los Angeles (with 19 drama projects retained) to become North America’s most attractive location for one-hour TV pilot production. Overall, Los Angeles retained only 90 projects (19 one-hour dramas and 71 half-hour comedies) out of 203 tracked during the ‘13/’14 development cycle, yielding a 44 percent pilot production share. Last year, L.A.’s pilot production share was 52 percent, and six years earlier, a commanding 82 percent. Leading competitors – including New York (35 total projects), Vancouver (17 total projects), Atlanta (12 total projects) and Toronto (8 total projects) – continue to gain ground on Los Angeles by attracting pilot producers with class-leading film incentive programs. Most of the pilot projects shot outside California were lucrative one-hour drama series produced for network, cable, or new media distribution. Including “straight-to-series” orders favored by new media content producers like Netflix, these projects cost $6 to $8 million to produce and employ 150-230 people during production. -

Pressing Her Emotions

"The Finellis" List of Awards (So Far) Los Angeles Film Awards • Winner - "Best Comedy" • Winner - "Best Web/TV Series Pilot" New York City Television Festival • Winner - "Best Television Series" • Winner - "Best Director" - Joris Hermans Amsterdam World Int'l Film Festival • Winner - "Best Television Series" Vegas Movie Awards • Winner - "Best Web/Television Pilot • 1st Runner-Up - "Best Song" ** London Independent Film Awards • Winner - "Best Web/Television Pilot" Rome Film Awards • Winner - "Best Television Series" • Finalist - "Best Song" ** German United Film Festival Berlin • Winner - "Best Television Series " Prague Int'l Monthly Film Festival • Winner - "Best Web/Television Series " Peak City Int'l Film Festival • Winner - "Best Foreign TV Series Pilot" After Hour Film Festival • Winner – "Best Television Series" South Shore Film Festival • Winner - “Best Comedy SitCom” • Winner - "Best Comedy SitCom Script" Cult Critic Movie Awards - Calcutta, India • Winner - "Best Web/Television Pilot" Vesuvius Int'l Monthly Film Festival - Naples, Italy • Winner - "Best Web/TV Series" Mediterranean Film Festival - Cannes • 1st Runner Up - "Best Television Series" ** All "Best Song" nominations are for "Here I Am Again" from Episode One of "The Finellis" ("The Homecoming") "Here I Am Again" music by Ulf Weidmann with lyrics by Mark Janicello "The Finellis" List of Nominations (So Far) Cult Critic Movie Awards - Calcutta, India • Finalist - "Jean Luc Goddard Award "Best TV Pilot or Series" London Independent Motion Picture Awards • Nominee - -

Film Schedule Summary Governors Crossing 14 1402 Hurley Drive Report Dates: Friday, August 17, 2018 - Thursday, August 23, 2018 Sevierville, TN 37862, (865) 366-1752

Film Schedule Summary Governors Crossing 14 1402 Hurley Drive Report Dates: Friday, August 17, 2018 - Thursday, August 23, 2018 Sevierville, TN 37862, (865) 366-1752 **************************************************************STARTING FRIDAY, AUG 17*************************************************************** ALPHA PG13 1 Hours 36 Minutes FRIDAY - THURSDAY 12:45 pm 02:55 pm 05:05 pm 07:15 pm 09:25 pm Kodi Smit-McPhee, Priya Rajaratnam, Leonor Varela, Jens Hultn, Natassia Malthe, Jhannes Haukur Jhannesson --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- *MILE 22 SXS R 1 Hours 36 Minutes FRIDAY - THURSDAY 12:20 pm 02:35 pm 04:50 pm 07:05 pm 09:20 pm Mark Wahlberg, Lauren Cohan, Ronda Rousey --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ************************************************************************CONTINUING************************************************************************ CRAZY RICH ASIANS PG13 2 Hours 1 Minutes FRIDAY - THURSDAY 01:00 pm 04:00 pm 07:00 pm 09:40 pm Constance Wu, Michelle Yeoh, Henry Golding --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- *THE MEG SXS PG13 1 Hours 53 Minutes FRIDAY - THURSDAY 11:50 am 02:20 pm 04:50 pm 07:20 pm 09:50 pm Ruby Rose, Jason Statham, Rainn Wilson -

TV Pilot Kit – Writers Store

TV Pilot Kit From The Writers Store Ever fantasized about creating your own TV show? Stop dreaming & start writing! The TV Pilot Kit is the perfect launching pad for writing a professional TV Pilot proposal. This kit includes elements that guide you through your Pilot Proposal, including logline, plot, and acts, along with a Character Map for determining your cast and their motivations. Plus, you’ll find illustrated examples using the pilot of How I Met Your Mother. Once you're finished, you can confirm with an expert that your completed Kit is ready to compete in the Industry via our TV Pilot Kit Development Notes. With this professional service, you get a written analysis on your proposal's viability, which is that the delicate balance of a set-up, payoff, and ongoing plot lines and character arcs. Plus, your completed TV Pilot Kit proposals can be used to enter the next round of The Industry Insider TV Writing Contest, where you can win unparalleled Industry experience, a meeting with an esteemed executive producer, and much more. 2 Contents Elements of TV Pilot Proposal 4 Character Map 5 Example of TV Pilot Proposal 9 How I Met Your Mother Example of Character Map 12 How I Met YOur Mother 3 Industry Insider TV Pilot Proposal 1-SERIES LOGLINE 2- WRITE BRIEF DESCRIPTIONS FOR EACH OF YOUR MAIN CHARACTERS 3. USE THE CHARACTER MAP TO WRITE BRIEF DESCRIPTIONS DETAILING HOW EACH CHARACTER FEELS ABOUT THE OTHER CHARACTERS 4. WRITE A BRIEF DESCRIPTION OF THE PLOTS IN THE PILOT EPISODE 4a. A PLOT 4b. -

Multi-Platinum Artist Brainpower Brings International Flavor to the Equalizer 2 with New Single

MULTI-PLATINUM ARTIST BRAINPOWER BRINGS INTERNATIONAL FLAVOR TO THE EQUALIZER 2 WITH NEW SINGLE MC Brainpower Continues to Claim His Spot in the Hip Hop World with Release of "Animal Sauvage" Los Angeles, California - The Equalizer 2, starring actor Denzel Washington, is expected to be the hottest movie of the summer. The new music from the thriller is starting to make its own noise, as well. The World Song Network is releasing a new, hot single "Animal Sauvage" from international powerhouse, Brainpower. With "Animal Sauvage", Brainpower, based in Amsterdam, takes the listeners on a hip hop journey through a high- impact, techno world. "Animal Sauvage", which is featured in the film, is now available on all digital platforms. Brainpower's "Animal Sauvage" features Stix, Pitcho and Pharoahe Monch. The song is a bilingual, international hip-hop/rock mashup representing Amsterdam, Holland, Brussels, Los Angeles, and New York. Jabari Ali, music supervisor for The Equalizer 2, saw Brainpower as a natural fit to the storyline of the film. "I respect the talent of Brainpower as an artist, songwriter and producer. This song tremendously enhances the story telling for the film," says Ali. Brainpower is a pioneering bilingual triple threat from Amsterdam, who has sold well over a million records as an artist/songwriter. He was the first hip hop artist to win the MTV Europe Music Awards for Best Dutch Act; and his Youtube channel has recently crossed the 10 million views mark. "I am humbled to be a part of a major blockbuster like The Equalizer 2. I have been a Denzel Washington fan all of my life, so this is just crazy! And I love Antoine Fuqua's body of work," says Brainpower. -

2018 Television Report

2018 Television Report PHOTO: HBO / Insecure 6255 W. Sunset Blvd. CREDITS: 12th Floor Contributors: Hollywood, CA 90028 Adrian McDonald Corina Sandru Philip Sokoloski filmla.com Graphic Design: Shane Hirschman @FilmLA FilmLA Photography: Shutterstock FilmLAinc HBO ABC FOX TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 2 PRODUCTION OF LIVE-ACTION SCRIPTED SERIES 3 THE INFLUENCE OF DIGITAL STREAMING SERVICES 4 THE IMPACT OF CORD-CUTTING CONSUMERS 4 THE REALITY OF RISING PRODUCTION COSTS 5 NEW PROJECTS: PILOTS VS. STRAIGHT-TO-SERIES ORDERS 6 REMAKES, REBOOTS, REVIVALS—THE RIP VAN WINKLE EFFECT 8 SERIES PRODUCTION BY LOCATION 10 SERIES PRODUCTION BY EPISODE COUNT 10 FOCUS ON CALIFORNIA 11 NEW PROJECTS BY LOCATION 13 NEW PROJECTS BY DURATION 14 CONCLUSION 14 ABOUT THIS REPORT 15 INTRODUCTION It is rare to find someone who does not claim to have a favorite TV show. Whether one is a devotee of a long-running, time-tested procedural on basic cable, or a binge-watching cord-cutter glued to Hulu© on Sunday afternoons, for many of us, our television viewing habits are a part of who we are. But outside the industry where new television content is conceived and created, it is rare to pause and consider how television series are made, much less where this work is performed, and why, and by whom, and how much money is spent along the way. In this study we explore notable developments impacting the television industry and how those changes affect production levels in California and competing jurisdictions. Some of the trends we consider are: growth in the number of live-action scripted series in production, the influence of digital streaming services on this number, increasing production costs and a turn toward remakes and reboots and away from traditional pilot production. -

Movie.List.11.10.20

Movies to borrow We hope you enjoy our movies! We allow only two movies at a time, but you more than welcome to trade them in as many times as you like. So that everyone gets a chance to watch them, we ask that all movies are returned by 3:00 pm the following day, please! Category Page New Releases 1 Action & Thrillers 4 Comedy 21 Drama 28 Family 35 Christmas 54 To borrow: just contact the front desk and let us know which movies you would like, and we will check to see if they are currently available for you. It will help if you are able to provide us with the catalog number, which is the number in parentheses next to the title and rating. You can pick up your DVDs at the front desk, and we ask that you please return them to us when you are finished. Thank you! 1 New Releases Antebellum (R) (367): Successful author Veronica Henley finds herself trapped in a horrifying reality and must uncover the mind-bending mystery before it's too late. Starring: Janelle Monae Hard Kill (R) (366): The work of billionaire tech CEO Donovan Chalmers is so valuable that he hires mercenaries to protect it, and a terrorist group kidnaps his daughter just to get it. Starring: Jesse Metcalfe, Bruce Willis Deep Blue Sea 3 (R) (365): Studying the effects of climate change off the coast of Mozambique, a marine biologist and her team confront three genetically enhanced bull sharks. Now, a new bloodbath is waiting to happen in the name of science. -

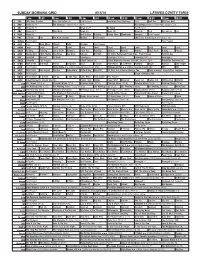

Sunday Morning Grid 8/14/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 8/14/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Incredible Dog Challenge Paid Golf Res. PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Rio Olympics Track and Field. (N) Å Rio Olympics Women’s Basketball: China vs. U.S. 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News (N) Paid Eye on L.A. Paid 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program 2016 U.S. Senior Open Final Round. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Mom Mkver Church Faith Dr. John Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Ellie’s Real Baking Project 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Ed Slott’s Retirement Road Map... From Forever Eat Dirt-Axe 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage (TV14) Å Leverage (TV14) Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Toluca vs Tigres República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Home Alone 3 › (1997, Comedia) Alex D.