History and Evaluation of the Mcintire-Stennis Cooperative Forestry Research Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Renews War on the Meat

-- v. SUGAE-- 96 Degree U. S. WEATHER BUREAU, JUNE 4. Last 24 hours rainfall, .00. Test Centrifugals, 3.47c; Per Ton, $69.10. Temperature. Max. 81; Min. 75. Weather, fair. 88 Analysis Beets, 8s; Per Ton, $74.20. ESTABLISHED JULV 2 1656 VOL. XLIIL, NO. 7433- - HONOLULU, HAWAII TERRITORY, TUESDAY, JUNE 5. 1906. PRICE FIVE CENTS. h LOUIS MARKS SCHOOL FUNDS FOSTER COBURN WILL THE ESIDENT SUCCEED BURTON IN KILLED BY RUfl VERY UNITED STATE SENATE RENEWS WAR ON THE AUTO LOW MEAT MEN t - 'is P A Big Winton Machine Less Than Ten Dollars His Message to Congress on the Evils of the , St- .- Over, Crushing Left for Babbitt's 1 Trust Methods Is Turns 4 Accompanied by the -- "1 His Skull. Incidentals, )-- Report of the Commissioner. ' A' - 1 A deplorable automobile accident oc- There are less than ten dollars left jln the stationery and incidental appro- curred about 9:30 last night, in wh'ch ' f. priation for the schol department, rT' Associated Press Cablegrams.) Louis Marks was almost instantly kill- do not know am ' "I what I going to 4-- WASHINGTON, June 5. In his promised message to Congress ed and Charles A. Bon received serious do about it," said Superintendent Bab- (9 yesterday upon the meat trust and its manner of conducting its busi bitt, yesterday. "We pay rents to injury tc his arm. The other occupants the ness, President Kooseveli urged the enactment of a law requiring amount of $1250 a year, at out 1 ! least, stringent inspection of of the machine, Mrs. Marks and Mrs. -

Committee on Appropriations UNITED STATES SENATE 135Th Anniversary

107th Congress, 2d Session Document No. 13 Committee on Appropriations UNITED STATES SENATE 135th Anniversary 1867–2002 U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 2002 ‘‘The legislative control of the purse is the central pil- lar—the central pillar—upon which the constitutional temple of checks and balances and separation of powers rests, and if that pillar is shaken, the temple will fall. It is...central to the fundamental liberty of the Amer- ican people.’’ Senator Robert C. Byrd, Chairman Senate Appropriations Committee United States Senate Committee on Appropriations ONE HUNDRED SEVENTH CONGRESS ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia, TED STEVENS, Alaska, Ranking Chairman THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi ANIEL NOUYE Hawaii D K. I , ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania RNEST OLLINGS South Carolina E F. H , PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico ATRICK EAHY Vermont P J. L , CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri OM ARKIN Iowa T H , MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky ARBARA IKULSKI Maryland B A. M , CONRAD BURNS, Montana ARRY EID Nevada H R , RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama ERB OHL Wisconsin H K , JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire ATTY URRAY Washington P M , ROBERT F. BENNETT, Utah YRON ORGAN North Dakota B L. D , BEN NIGHTHORSE CAMPBELL, Colorado IANNE EINSTEIN California D F , LARRY CRAIG, Idaho ICHARD URBIN Illinois R J. D , KAY BAILEY HUTCHISON, Texas IM OHNSON South Dakota T J , MIKE DEWINE, Ohio MARY L. LANDRIEU, Louisiana JACK REED, Rhode Island TERRENCE E. SAUVAIN, Staff Director CHARLES KIEFFER, Deputy Staff Director STEVEN J. CORTESE, Minority Staff Director V Subcommittee Membership, One Hundred Seventh Congress Senator Byrd, as chairman of the Committee, and Senator Stevens, as ranking minority member of the Committee, are ex officio members of all subcommit- tees of which they are not regular members. -

19-04-HR Haldeman Political File

Richard Nixon Presidential Library Contested Materials Collection Folder List Box Number Folder Number Document Date No Date Subject Document Type Document Description 19 4 Campaign Other Document From: Harry S. Dent RE: Profiles on each state regarding the primary results for elections. 71 pgs. Monday, March 21, 2011 Page 1 of 1 - Democratic Primary - May 5 111E Y~'ilIIE HUUSE GOP Convention - July 17 Primary Results -- --~ -~ ------- NAME party anncd fiJ cd bi.lc!<ground GOVERNORIS RACE George Wallace D 2/26 x beat inc Albert Brewer in runoff former Gov.; 68 PRES cando A. C. Shelton IND 6/6 former St. Sen. Dr. Peter Ca:;;hin NDPA endorsed by the Negro Democratic party in Aiabama NO SENATE RACE CONGRESSIONAL 1st - Jack Edwards INC R x x B. H. Mathis D x x 2nd - B ill Dickenson INC R x x A Ibert Winfield D x x 3rd -G eorge Andrews INC D x x 4th - Bi11 Nichols INC D x x . G len Andrews R 5th -W alter Flowers INC D x x 6th - John Buchanan INC R x x Jack Schmarkey D x x defeated T ito Howard in primary 7th - To m Bevill INC D x x defeated M rs. Frank Stewart in prim 8th - Bob Jones INC D x x ALASKA Filing Date - June 1 Primary - August 25 Primary Re sults NAME party anned filed bacl,ground GOVERNOR1S RACE Keith Miller INC R 4/22 appt to fill Hickel term William Egan D former . Governor SENATE RACE Theodore Stevens INC R 3/21 appt to fill Bartlett term St. -

HOUSE of REPRESENTATIVES to Increase Agricultural Purchasing Power and to Meet the Need of Combating Mr

1942' CONGRESSIONAL RECORD-HOUSE 5241: - ADJOURNMENT .- 1 bill to · provide for recip,rocal .pri-vileges with 1 defense-pz:ogram and.a.reenactmen1 of legisla- ·_ Mr. PRIEST.- Mr.-· sp_eaker·, 1 ·move· F.espt)ct to the filing· of applications, for pat-· 1 1(l.on - si-milar, ~ that -of ~ 1917 and,.. so give· to, ~nts for inventions, and for other purposes;: the young men pf 194:2_ the , protection- .th~r that the Rouse do now adjourn: - -- - to the Committee on ·Patents. fathers had in 1917; to the Committee on . The motion was agree·d· to; accordingly 1756. A letter · from the Secretary of the Military Affairs. · (at 2 o'clock and 12 minutes p. m.) the Interior, transmitting herewith, pursuant to 3065. By Mr. HEIDINGER: Petition of Mrs. House adjourned until tomorrow, Tues-· the act of June 22, 1936 (49 Stat. 1803). a E C. Jacobs and 38 other residents of Flora, day, June 1~, 1942, .at 12 o'clock noon. report dated November 30, 1939, of economic Ill., urging the enactment of Senate bill conditions· affecting certain lands of the' irri- 860; trr the Committee on Military Affairs . gation project under t-he jurisdiction of the 3066. By Mr. LYNCH: Resolution of · the: Oroville-Tonasket irrigation district in the Butchers' Union of Greater New York and COMMITTEE HEARINGS State of Washington; also ~ draft of bill to vicinity, urging increases in pay for postal Cq~MITTEE 0~ PUB~IC ~UILDINGS AND GROUNDS provide relief t_o the own.ers of former Indian employees; to the Committee on the Post There will be a meeting of the com-. -

Early 2016 Newsletters

Scituate Historical Society 43 Cudworth Road, Scituate, MA 02066, 781-545-1083 On Facebook at www.facebook.com/ScituateHistoricalSociety or at scituatehistoricalsociety.org Making Progress on CPC Projects The Cushing Shay is returned to mint condition while the Lafayette Coach begins its journey back to full health A Trove of Stories Arrives Two months ago a box was delivered by post to the Little Red Schoolhouse. On a Sunday afternoon, the box was opened and a cascade of history tumbled out. The box came from the Franzen family of Scituate and New Hampshire. The materials included ran a gamut from 1840 to 1945. Photographs, letters, portraits, lithographs, and a one of a kind medal were included. See the photos below for a hint at this amazing donation. We can not be more grateful. The Coast Guard of a bygone day An extremely rare medal given to each Scituate sol- dier or sailor who returned from World War 1. This is believed to be William Franzen during the First World War. The North Jetty in ice—1913 Captain George Brown of the Sailors muster at the Dedication of Life Saving service the Monument at Lawson Common The Dr. Harold Edgerton /Graves End Bell Comes to Rest at Scituate Light Thanks are due to many hands for the installation of the Dr. Harold Edgerton /Graves End Bell at Scituate Light in early December. We are in debt to Bob Chessia, Bob Steverman, Steve Litchfield, Scituate Concrete Pipe, and especially the generous team at MIT who coordinated this gift. Pictured with the bell is Gary Tondorf- Dick , Project Manager for MIT Facilities, who had a bell on his hands and knew just where he wanted it to land. -

NPRC) VIP List, 2009

Description of document: National Archives National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) VIP list, 2009 Requested date: December 2007 Released date: March 2008 Posted date: 04-January-2010 Source of document: National Personnel Records Center Military Personnel Records 9700 Page Avenue St. Louis, MO 63132-5100 Note: NPRC staff has compiled a list of prominent persons whose military records files they hold. They call this their VIP Listing. You can ask for a copy of any of these files simply by submitting a Freedom of Information Act request to the address above. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. -

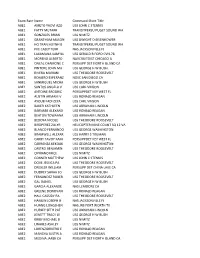

Exam Rate Name Command Short Title ABE1 AMETO YAOVI AZO

Exam Rate Name Command Short Title ABE1 AMETO YAOVI AZO USS JOHN C STENNIS ABE1 FATTY MUTARR TRANSITPERSU PUGET SOUND WA ABE1 GONZALES BRIAN USS NIMITZ ABE1 GRANTHAM MASON USS DWIGHT D EISENHOWER ABE1 HO TRAN HUYNH B TRANSITPERSU PUGET SOUND WA ABE1 IVIE CASEY TERR NAS JACKSONVILLE FL ABE1 LAXAMANA KAMYLL USS GERALD R FORD CVN-78 ABE1 MORENO ALBERTO NAVCRUITDIST CHICAGO IL ABE1 ONEAL CHAMONE C PERSUPP DET NORTH ISLAND CA ABE1 PINTORE JOHN MA USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE1 RIVERA MARIANI USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE1 ROMERO ESPERANZ NOSC SAN DIEGO CA ABE1 SANMIGUEL MICHA USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE1 SANTOS ANGELA V USS CARL VINSON ABE2 ANTOINE BRODRIC PERSUPPDET KEY WEST FL ABE2 AUSTIN ARMANI V USS RONALD REAGAN ABE2 AYOUB FADI ZEYA USS CARL VINSON ABE2 BAKER KATHLEEN USS ABRAHAM LINCOLN ABE2 BARNABE ALEXAND USS RONALD REAGAN ABE2 BEATON TOWAANA USS ABRAHAM LINCOLN ABE2 BEDOYA NICOLE USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 BIRDPEREZ ZULYR HELICOPTER MINE COUNT SQ 12 VA ABE2 BLANCO FERNANDO USS GEORGE WASHINGTON ABE2 BRAMWELL ALEXAR USS HARRY S TRUMAN ABE2 CARBY TAVOY KAM PERSUPPDET KEY WEST FL ABE2 CARRANZA KEKOAK USS GEORGE WASHINGTON ABE2 CASTRO BENJAMIN USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 CIPRIANO IRICE USS NIMITZ ABE2 CONNER MATTHEW USS JOHN C STENNIS ABE2 DOVE JESSICA PA USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 DREXLER WILLIAM PERSUPP DET CHINA LAKE CA ABE2 DUDREY SARAH JO USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE2 FERNANDEZ ROBER USS THEODORE ROOSEVELT ABE2 GAL DANIEL USS GEORGE H W BUSH ABE2 GARCIA ALEXANDE NAS LEMOORE CA ABE2 GREENE DONOVAN USS RONALD REAGAN ABE2 HALL CASSIDY RA USS THEODORE -

Sophia's Dowry

Summer 2018 Volume 1, Issue 1 Sophia’s Dowry Newsletter of the Colonel Aquila Hall Chapter Maryland Society, Sons of the American Revolution Harford County, Maryland President’s Message Compatriots, It is hard to believe that the semi-annual is just around the corner. The chapter continues to work to fulfill the objectives of our Society. On June 14th, Flag Day, members Dave Hoover, Chris Smithson, Ed Miller, Jeff Springer and myself handed out flags to our fellow citizens at the Harford County Court House. The week before congress the Col. Aquila Hall chapter SAR joined with the ladies of the Harbor of Grace and William Paca chapters as well as the Bush Declaration Society, C.A.R. and participated in the Be Air 4th of July parade. Chapter members Chris Smithson, Bill Smithson, Dave Hoover, Frank Blake, Sam Raborg and I participated. Thanks to the efforts of Bill Smithson and Sandi Wallis and Elizabeth Wrona and others, we won first place in the floats Sam and Lou Raborg at the grave of Brigadier General Mordecai Gist (1742-1792) at St. Michael’s Church division. Cemetery in Charleston, South Carolina. A week later, my wife and I attended the National Congress in Houston along with chapter members, Bill Smithson and Dave Hoover. On Aug. 4th I attended the Col. Aquila Hall Summer cookout hosted by compatriot David Hoover and his wife Susan Brown. On August 10-12th, 2018 my wife and I attended the Atlantic Middle States Association annual Tell The Story …. meeting at the Marriot Center City in Newport News, Virginia. -

Constitutionalism and the Foundations of the Security State Aziz Rana Cornell Law School, [email protected]

Cornell University Law School Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository Cornell Law Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 4-2015 Constitutionalism and the Foundations of the Security State Aziz Rana Cornell Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/facpub Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Legal History, Theory and Process Commons, and the National Security Commons Recommended Citation Aziz Rana, "Constitutionalism and the Foundations of the Security State," 103 California Law Review (2015) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Constitutionalism and the Foundations of the Security State Aziz Rana Scholars often argue that the culture of American constitutionalism provides an important constraint on aggressive national security practices. This Article challenges the conventional account by highlighting instead how modern constitutional reverence emerged in tandem with the national security state, critically functioning to reinforce and legitimize government power rather than primarily to place limits on it. This unacknowledged security origin of today’s constitutional climate speaks to a profound ambiguity in the type of public culture ultimately promoted by the Constitution. Scholars are clearly right to note that constitutional loyalty has created political space for arguments more respectful of civil rights and civil liberties, making the very worst excesses of the past less likely. At the same time, however, public discussion about protecting the Constitution—and a distinctively American way of life—has also served as a key justification for strengthening the government’s security infrastructure over the long run. -

Committee on Appropriations UNITED STATES SENATE

110th Congress, 2d Session Document No. 14 Committee on Appropriations UNITED STATES SENATE 1867–2008 U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 2008 ‘‘No Money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law; and a regular Statement and Account of the Receipts and Expenditures of all public Money shall be published from time to time. Constitution of the United States—Article I, Section 9 ‘‘This power over the purse may, in fact, be regarded as the most complete and effectual weapon with which any constitution can arm the immediate representatives of the people, for obtaining a redress of every grievance, and for carrying into effect every just and salutary meas- ure.’’ James Madison, Federalist 58 ‘‘The legislative control of the purse is the central pillar—the central pillar—upon which the constitutional temple of checks and balances and separation of powers rests, and if that pillar is shaken, the temple will fall. It is...central to the fundamental liberty of the American peo- ple.’’ Senator Robert C. Byrd, Chairman Senate Appropriations Committee United States Senate Committee on Appropriations ONE HUNDRED TENTH CONGRESS ROBERT C. BYRD, West Virginia, THAD COCHRAN, Mississippi, Ranking Chairman TED STEVENS, Alaska ANIEL NOUYE Hawaii D K. I , ARLEN SPECTER, Pennsylvania ATRICK EAHY Vermont P J. L , PETE V. DOMENICI, New Mexico OM ARKIN Iowa T H , CHRISTOPHER S. BOND, Missouri ARBARA IKULSKI Maryland B A. M , MITCH MCCONNELL, Kentucky ERB OHL Wisconsin H K , RICHARD C. SHELBY, Alabama ATTY URRAY Washington P M , JUDD GREGG, New Hampshire YRON ORGAN North Dakota B L. -

National Register of Historic Places NATIONAL Registration Form REGISTER

NPS Form 10-900 QMS Mo. 10244)018 (Rev. 8-86) 'i r-:i United States Department of the Interior - LS j'! ! National Park Service -.; 17 ^ LJ National Register of Historic Places NATIONAL Registration Form REGISTER This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, styles, materials, and areas of significance, enter only the categories and subcategories listed in the instructions. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10-900a). Type all entries. 1. Name of Property_________________________________________________ historic name___________fhamVvvrl^'in f^a.r>TTiP> K^i-lpi. Hmific* other names/site number 2. Location street & number 1927 NE Tillainook Street N// ^J not for publication city, town Portland N// Jvicinity state Oregon code QR county Multnomah code 051 zip code97212 3. Classification Ownership of Property Category of Property Number of Resources within Property [y~l private H building(s) Contributing Noncontributing I I public-local I district 1 ____ buildings I I public-State [site ____ ____ sites I I public-Federal I structure ____ ____ structures I object ____ ____ objects 1 n Total Name of related multiple property listing: Number of contributing resources previously ___________M/ft________________ listed in the National Register N/A___ 4. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this [X] nomination EH request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. -

Land and Law in the Age of Enterprise: a Legal History of Railroad Land Grants in the Pacific Northwest, 1864-1916 Sean M

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, History, Department of Department of History 5-2015 Land and Law in the Age of Enterprise: A Legal History of Railroad Land Grants in the Pacific Northwest, 1864-1916 Sean M. Kammer University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historydiss Part of the Legal Commons, and the United States History Commons Kammer, Sean M., "Land and Law in the Age of Enterprise: A Legal History of Railroad Land Grants in the Pacific orN thwest, 1864-1916" (2015). Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History. 84. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historydiss/84 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, & Student Research, Department of History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. LAND AND LAW IN THE AGE OF ENTERPRISE: A LEGAL HISTORY OF RAILROAD LAND GRANTS IN THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST, 1864 - 1916 by Sean M. Kammer A DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Major: History Under the Supervision of Professor William G. Thomas III Lincoln, Nebraska May, 2015 LAND AND LAW IN THE AGE OF ENTERPRISE: A LEGAL HISTORY OF RAILROAD LAND GRANTS IN THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST, 1864 – 1916 Sean M. Kammer, Ph.D. University of Nebraska, 2015 Adviser: William G. Thomas III Federal land subsidies to railroad corporations comprised an important part of the federal government’s policies towards its western land domain in the middle decades of the nineteenth century.