SUSSMAN-DISSERTATION-2017.Pdf (1.420Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The History Spiritualism

THE HISTORY of SPIRITUALISM by ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE, M.D., LL.D. former President d'Honneur de la Fédération Spirite Internationale, President of the London Spiritualist Alliance, and President of the British College of Psychic Science Volume One With Seven Plates PSYCHIC PRESS LTD First edition 1926 To SIR OLIVER LODGE, M.S. A great leader both in physical and in psychic science In token of respect This work is dedicated PREFACE This work has grown from small disconnected chapters into a narrative which covers in a way the whole history of the Spiritualistic movement. This genesis needs some little explanation. I had written certain studies with no particular ulterior object save to gain myself, and to pass on to others, a clear view of what seemed to me to be important episodes in the modern spiritual development of the human race. These included the chapters on Swedenborg, on Irving, on A. J. Davis, on the Hydesville incident, on the history of the Fox sisters, on the Eddys and on the life of D. D. Home. These were all done before it was suggested to my mind that I had already gone some distance in doing a fuller history of the Spiritualistic movement than had hitherto seen the light - a history which would have the advantage of being written from the inside and with intimate personal knowledge of those factors which are characteristic of this modern development. It is indeed curious that this movement, which many of us regard as the most important in the history of the world since the Christ episode, has never had a historian from those who were within it, and who had large personal experience of its development. -

The Science of Mediumship and the Evidence of Survival

Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online Master of Liberal Studies Theses 2009 The cS ience of Mediumship and the Evidence of Survival Benjamin R. Cox III [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls Recommended Citation Cox, Benjamin R. III, "The cS ience of Mediumship and the Evidence of Survival" (2009). Master of Liberal Studies Theses. 31. http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls/31 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Liberal Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Science of Mediumship and the Evidence of Survival A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Liberal Studies by Benjamin R. Cox, III April, 2009 Mentor: Dr. J. Thomas Cook Rollins College Hamilton Holt School Master of Liberal Studies Winter Park, Florida This project is dedicated to Nathan Jablonski and Richard S. Smith Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................... 1 The Science of Mediumship.................................................................... 11 The Case of Leonora E. Piper ................................................................ 33 The Case of Eusapia Palladino............................................................... 45 My Personal Experience as a Seance Medium Specializing -

Historical Perspective

Journal of Scientific Exploration, Vol. 34, No. 4, pp. 717–754, 2020 0892-3310/20 HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE Early Psychical Research Reference Works: Remarks on Nandor Fodor’s Encyclopaedia of Psychic Science Carlos S. Alvarado [email protected] Submitted March 11, 2020; Accepted July 5, 2020; Published December 15, 2020 DOI: 10.31275/20201785 Creative Commons License CC-BY-NC Abstract—Some early reference works about psychic phenomena have included bibliographies, dictionaries, encyclopedias, and general over- view books. A particularly useful one, and the focus of the present article, is Nandor Fodor’s Encyclopaedia of Psychic Science (Fodor, n.d., circa 1933 or 1934). The encyclopedia has more than 900 alphabetically arranged entries. These cover such phenomena as apparitions, auras, automatic writing, clairvoyance, hauntings, materialization, poltergeists, premoni- tions, psychometry, and telepathy, but also mediums and psychics, re- searchers and writers, magazines and journals, organizations, theoretical ideas, and other topics. In addition to the content of this work, and some information about its author, it is argued that the Encyclopaedia is a good reference work for the study of developments from before 1933, even though it has some omissions and bibliographical problems. Keywords: Encyclopaedia of Psychic Science; Nandor Fodor; psychical re- search reference works; history of psychical research INTRODUCTION The work discussed in this article, Nandor Fodor’s Encyclopaedia of Psychic Science (Fodor, n.d., circa 1933 or 1934), is a unique compilation of information about psychical research and related topics up to around 1933. Widely used by writers interested in overviews of the literature, Fodor’s work is part of a reference literature developed over the years to facilitate the acquisition of knowledge about the early publications of the field by students of psychic phenomena. -

Physiology Or Psychic Powers? William Carpenter and the Debate Over Spiritualism in Victorian Britain

Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences xxx (2014) 1e10 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/shpsc Physiology or psychic powers? William Carpenter and the debate over spiritualism in Victorian Britain Shannon Delorme History of Science, University of Oxford, New College, Holywell Street, OX1 3BN Oxford, United Kingdom article info abstract Article history: This paper analyses the attitude of the British Physiologist William Benjamin Carpenter (1813e1885) to Available online xxx spiritualist claims and other alleged psychical phenomena in the second half of the Nineteenth Century. It argues that existing portraits of Carpenter as a critic of psychical studies need to be refined so as to Keywords: include his curiosity about certain ‘unexplained phenomena’, as well as broadened so as to take into Spiritualism account his overarching epistemological approach in a context of theological and social fluidity within Psychical research nineteenth-century British Unitarianism. Carpenter’s hostility towards spiritualism has been well Neurophysiology documented, but his interest in the possibility of thought-transference or his secret fascination with the Unitarianism ’ William B. Carpenter medium Henry Slade have not been mentioned until now. This paper therefore highlights Carpenter s Religious naturalism ambivalences and focuses on his conciliatory attitude towards a number of heterodoxies while sug- gesting that his Unitarian faith offers the keys to understanding his unflinching rationalism, his belief in the enduring power of mind, and his effort to resolve dualisms. Ó 2014 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. When citing this paper, please use the full journal title Studies in History and Philosophy of Biological and Biomedical Sciences 1. -

James Curtis and Spiritualism in Nineteenth-Century Ballarat

James Curtis and Spiritualism in Nineteenth-Century Ballarat Greg Young This thesis is submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Faculty of Education and Arts Federation University University Drive, Mount Helen Ballarat 3353 Victoria, Australia STATEMENT OF AUTHORSHIP Except where explicit reference is made in the text this thesis contains no material published elsewhere or extracted in whole or in part from a thesis by which I have qualified for or been awarded another degree of diploma. No other person’s work has been relied upon or used without due acknowledgement in the main text and bibliography. Signed (Applicant): Date: Signed (Supervisor): Date: When the intellectual and spiritual history of the nineteenth century comes to be written, a highly interesting chapter in it will be that which records the origin, growth, decline, and disappearance of the delusion of spiritualism. —Australasian Saturday 25 October 1879 Acknowledgements I am greatly indebted to my University of Ballarat (now Federation University) supervisors Dr Anne Beggs Sunter, Dr Jill Blee, and Dr David Waldron for their encouragement, advice, and criticism. It is also a pleasure to acknowledge a large debt of gratitude to Professor Tony Milner and Professor John Powers, both of the Australian National University, for their generous support. This project began in the Heritage Library of the Ballaarat Mechanics’ Institute; I am grateful to the BMI for its friendly help. Dedication To Anne, Peter, Charlotte, and my teacher Dr Rafe de Crespigny. Abstract This thesis is about the origins, growth, and decline of spiritualism in nine- teenth-century Ballarat. -

Dissociation and the Unconscious Mind: Nineteenth-Century Perspectives on Mediumship

Journal of Scientifi c Exploration, Vol. 34, No. 3, pp. 537–596, 2020 0892-3310/20 HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE Dissociation and the Unconscious Mind: Nineteenth-Century Perspectives on Mediumship C!"#$% S. A#&!"!'$ Parapsychology Foundation [email protected] Submitted December 18, 2019; Accepted March 21, 2020; Published September 15, 2020 https://doi.org/10.31275/20201735 Creative Commons License CC-BY-NC Abstract—There is a long history of discussions of mediumship as related to dissociation and the unconscious mind during the nineteenth century. A! er an overview of relevant ideas and observations from the mesmeric, hypnosis, and spiritualistic literatures, I focus on the writings of Jules Baillarger, Alfred Binet, Paul Blocq, Théodore Flournoy, Jules Héricourt, William James, Pierre Janet, Ambroise August Liébeault, Frederic W. H. Myers, Julian Ochorowicz, Charles Richet, Hippolyte Taine, Paul Tascher, and Edouard von Hartmann. While some of their ideas reduced mediumship solely to intra-psychic processes, others considered as well veridical phenomena. The speculations of these individuals, involving personation, and di" erent memory states, were part of a general interest in the unconscious mind, and in automatisms, hysteria, and hypnosis during the period in question. Similar ideas continued into the twentieth century. Keywords: mediumship; dissociation; secondary personalities; Frederic W. H. Myers; Théodore Flournoy; Pierre Janet INTRODUCTION Dissociation, a process involving the disconnection of a sense of identity, physical sensations, and memory from conscious experience, has been related to mediumship due to the latter’s sensory and motor automatism and changes of identity. In recent years there have been some conceptual discussions of dissociation and mediumship (e.g., Maraldi et al., 2019) as well as empirical studies exploring their 538 Carlos S. -

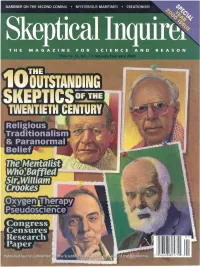

Here Are Many Heroes of the Skeptical Movement, Past and Present

THE COMMITTEE FOR THE SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATION OF CLAIMS OF THE PARANORMAL AT THE CENTER FOR INQUIRY-INTERNATIONA! (ADJACENT TO THE STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK AT BUFFALO) • AN INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy. State University of New York at Buffalo Barry Karr, Executive Director Joe Nickell, Senior Research Fellow Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director FELLOWS James E. Alcock,* psychologist. York Univ., Thomas Gilovich, psychologist, Cornell Univ. Dorothy Nelkin, sociologist, New York Univ. Toronto Henry Gordon, magician, columnist, Joe Nickell,* senior research fellow, CSICOP Steve Allen, comedian, author, composer, Toronto Lee Nisbet* philosopher, Medaille College pianist Stephen Jay Gould, Museum of Bill Nye, science educator and television Jerry Andrus, magician and inventor, Comparative Zoology, Harvard Univ. host, Nye Labs Albany, Oregon Susan Haack, Cooper Senior Scholar in Arts James E. Oberg, science writer Robert A. Baker, psychologist, Univ. of and Sciences, prof, of philosophy, Loren Pankratz, psychologist Oregon Kentucky University of Miami Stephen Barrett, M.D., psychiatrist, author, C. E. M. Hansel, psychologist Univ. of Wales Health Sciences Univ. consumer advocate, Allentown, Pa. Al Hibbs, scientist. Jet Propulsion Laboratory John Paulos, mathematician. Temple Univ. Barry Beyerstein, * biopsychologist, Simon Douglas Hofstadter, professor of human W. V. Quine, philosopher, Harvard Univ. Fraser Univ., Vancouver, B.C., Canada understanding and cognitive science, Milton Rosenberg, psychologist. Univ. of Irving Biederman, psychologist, Univ. of Indiana Univ. Chicago Southern California Gerald Holton, Mallinckrodt Professor of Wallace Sampson, M.D., clinical professor Susan Blackmore, psychologist, Univ. of the Physics and professor of history of science, of medicine, Stanford Univ. West of England, Bristol Harvard Univ. -

AR Wallace's Approach

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Apollo Volume 5, No. 4 16 Evolutionism Combined with Spiritualism: A. R. Wallace’s Approach ∗ Li LIU Peking University Abstract: A. R. Wallace was the co-founder of the theory of natural selection and a solid supporter of Darwin, but he combined evolutionism with spiritualism, and tried to understand human evolution and evolutionary ethics with a spiritualistic teleology. This teleological version is a typical example of non-Darwinian evolutionism , which was rooted in the ideology of Victorian progressionism, and was used to avoid the materialism implicated in Darwinism. Through investigating Wallace's approach, we may realize how progressionism had worked as the bridge between science and religion in Victorian Age. Key Words: A. R. Wallace, evolutionism, spiritualism, Victorian progressionism ∗ Department of Philosophy, Peking University, Beijing, 100871, China. E-mail: [email protected] Journal of Cambridge Studies 17 1. INTRODUCTION Alfred Russel Wallace and Charles Robert Darwin independently discovered the principle of natural selection and their articles were announced to scientific community by a joint publication, on 1st July 1858. It’s the starting point of the Darwinian revolution or as Peter Bowler put in his book, “the non-Darwinian revolution”. Stimulated by Wallace, Darwin finally finished and then published his Origin of Species, and got “the whole credit for one of the most liberating advances in scientific thought”, as Wallace “agreed of his own free will to play moon to Darwin’s sun.”1 Considered as a Darwinist, Wallace positively defended Darwinism in his time, and published a book named Darwinism (1889). -

Theory in Magic a Capstone Course for Majors in Religious Studies

Theory in Magic A Capstone Course for Majors in Religious Studies David Walker University of California, Santa Barbara Institutional Setting: The University of California at Santa Barbara, one of ten UC campuses, is a large public institution with some 18,000 undergraduate and 3,000 graduate students. Although boasting certain strengths in the natural and social sciences (financial resources, number of faculty, and number of majors), UCSB has excellent programs also in the humanities and fine arts, and the university has worked to develop and promote them since the 1960s. Among these is the program in Religious Studies, and it is both an indicative and special case of UCSB’s focus on the humanities: formed in 1964, the Department of Religious Studies is by far the largest such department in the UC system, with over 25 faculty members and continuing lecturers, offering a BA degree program and MA and PhD degrees in several subfields. The department is unique also nationally and internationally, being one of the first public academic programs supporting a secular approach to the study of matters religious; and it ranks consistently among the top programs in the field. There are currently 6 faculty members working in the subfield of Religion in the Americas. Curricular Setting: The Department of Religious Studies has been working to provide greater cohesion to its undergraduate major. Whereas the graduate programs are tracked through a series of complementary and cumulative classes, the department has hesitated to implement such a structure for the undergraduate degree. This is in part because many undergraduates declare majors towards the end of their time at UCSB, rather than at the beginning; and the department worries that too many prerequisite or sequenced courses may frustrate students’ ability to “find their niche” without “backtracking” to lower-level offerings. -

Spiritualism : Is Communication with the Spirit World an Established Fact?

ti n Is Communhatm with Be an established fact? flRH ^H^^^^^H^K^^^^^^^^^^I^^B^^H^^^I^^^^^^^B^^^^HI^^^^^H bl™' ^^^^^H^^HHS^^ffiiyS^^H^^^^^^^^^I^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^BH^^BiHwv^ 1 f \ 1 PRO—WAKE COOK^H hi ''^KSBm 1 CON FRANK P0DM0rE9I i 1 l::| - ; Hodgson, AMEfilC^^ secret; ^, FLAub, B BOYLSTOtl BOSTOxM, MASS. Boston Medical Library 8 The Fenway The Pro and Con Series EDITED BY HENRY MURRAY VOL. II. /l 6 Br SPIRITUALISM " ^ SPIRITUALISM IS COMMUNICATION WITH THE SPIRIT WORLD AN ESTABLISHED FACT? PRO—E. WAKE COOK AUTHOR OF '•' THE OEGANISATION OF MAlfKIND " 'THE INCREASING PURPOSE" ETC. CON—FRANK PODMORE AUTHOR OF " MODERN SPIRITUALISM " " STUDIES IN PSYCHICAL RESEARCH" ETC. AUDI ALTERAM PARTEM LONDON ISBISTER AND COMPANY LIMITED 15 & 16 TAVISTOCK ST. COVENT GARDEN 1903 / 9. cA:/d9, Printed by Ballantyne, Hanson &> Co. London <&» Edinburgh '-OCIETY FO.- KEbt-i^i^^^- f5 BOVi-^S-V.ss. BOSTON. SPIRITUALISM—PRO BY E. WAKE COOK A Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Open Knowledge Commons and Harvard Medical School http://www.archive.org/details/spiritualismiscoOOcook SPIRITUALISM IS COMMUNICATION WITH THE SPIRIT-WORLD AN ESTABLISHED FACT? PRO PAKT I The mystery of Existence deepens. Physical Science, whose splendid advance promised to make all things clear, is taking us into mys- terious wonder-worlds, revealing profounder depths than were ever dreamt of in our philosophies, and making greater and greater demands on our powers of belief. Materialism, never either philosophically or scientifically sound, seems now to be suspended in mid-air like Mahomet's coffin. What is matter ? No one can tell us ; Sir Oliver Lodge asserting that we know more of electricity than of matter. -

Newspaper, Spiritualism, and British Society, 1881 - 1920

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 12-2009 'Light, More Light': The 'Light' Newspaper, Spiritualism, and British Society, 1881 - 1920. Brian Glenney Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the European History Commons Recommended Citation Glenney, Brian, "'Light, More Light': The 'Light' Newspaper, Spiritualism, and British Society, 1881 - 1920." (2009). All Theses. 668. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/668 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "LIGHT, MORE LIGHT”: The “Light” Newspaper, Spiritualism and British Society, 1881-1920. A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Masters in History by Brian Edmund Glenney December, 2009 Accepted by: Dr. Michael Silvestri, Committee Chair Dr. Alan Grubb Dr. Megan Taylor Shockley i ABSTRACT This thesis looks at the spiritualist weekly Light through Late Victorian, Edwardian, and World War I Britain. Light has never received any extended coverage or historical treatment yet it was one of the major spiritualist newspapers during this part of British history. This thesis diagrams the lives of Light ’s first four major editors from 1881 till the end of World War I and their views on the growth of science, God, Christ, evolution, and morality. By focusing on one major spiritualist newspaper from 1881 till 1920, this thesis attempts to bridge the gap in spiritualist historiography that marks World War I as a stopping or starting point. -

The Purposes of History? Curriculum Studies, Invisible Objects and Twenty- first Century Societies

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: Baker, Bernadette (2013) The purposes of history? Curriculum studies, invisible objects and twenty- first century societies. Journal of Curriculum Theorizing, 29(1), pp. 25-47. This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/89916/ c The authors Individual non-commercial use only. Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. http:// journal.jctonline.org/ index.php/ jct/ article/ view/ 409 FEATURE ARTICLE The Purposes of History? Curriculum Studies, Invisible Objects and Twenty- first Century Societies BERNADETTE BAKER University of Wisconsin-Madison N DECONSTRUCTING HISTORY, Alun Munslow (2006, p. 1) articulates what is now I commonplace, that “It is generally recognised that written history is contemporary or present orientated to the extent that we historians not only occupy a platform in the here-and-now, but also hold positions on how we see the relationship between the past and its traces, and the manner in which we extract meaning from them. There are many reasons, then, for believing we live in a new intellectual epoch – a so-called postmodern age – and why we must rethink the nature of the historical