Read More (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charleston Archives, Libraries, And

Note: Names of contact people may have changed. A GUIDE TO CHARLESTON AREA ARCHIVES, LIBRARIES AND MUSEUMS “More than forty miles of shelves…” by Donald Macbeth, ca. 1906 Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Online Catalog http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2014650185/ 5th Edition 2015 CALM Directory 2015 The Charleston Archives, Libraries and Museums Council (CALM) was organized in 1985 with the goal to start cooperative disaster preparedness planning. David Moltke-Hansen (at that time Director of the South Carolina Historical Society) coordinated 22 local cultural organizations into a group that could provide mutual assistance after storms or other disasters. The organization helped foster communication, local efforts of recovery, sharing of resources and expertise. CALM helped agencies, organizations, and institutions write disaster plans; sponsored workshops; and in general, raised consciousness about preservation and disaster preparedness and recovery needs. The statewide Palmetto Archives, Libraries and Museums Council on Preservation (PALMCOP) was then formed in Columbia in 1986 based on the successful model of CALM. CALM now provides an opportunity for participants in the archives, library, museum and records communities to interact in a supportive environment for the exchange of ideas and information. In 2001, CALM members created the Guide to Charleston Area Archives, Libraries and Museums to assist librarians, archivists, curators, and records managers in knowing “who has what,” and also to assist local researchers and scholars in their educational and academic pursuits. It was updated in 2004, 2008, and 2011, however, significant staffing and other changes have occurred in the last four years and this 5th edition reflects those changes. -

Southern Jewish History

SOUTHERN JEWISH HISTORY Journal of the Southern Jewish Historical Society Mark K. Bauman, Editor Rachel B. Heimovics, Managing Editor Eric L. Goldstein, Book Review Editor 2 0 0 4 Volume 7 Southern Jewish History Mark K. Bauman, Editor Rachel B. Heimovics, Managing Editor Eric L. Goldstein, Book Review Editor Editorial Board Elliott Ashkenazi Martin Perlmutter Canter Brown, Jr. Marc Lee Raphael Eric Goldstein Stuart Rockoff Cheryl Greenberg Bryan Stone Scott Langston Clive Webb Phyllis Leffler George Wilkes Southern Jewish History is a publication of the Southern Jewish Historical Society and is available by subscription and as a benefit of membership in the Society. The opinions and statements expressed by contributors are not neces- sarily those of the journal or of the Southern Jewish Historical Society. Southern Jewish Historical Society OFFICERS: Minette Cooper, President; Sumner Levine, President-Elect; Scott M. Langston, Secretary; Bernard Wax, Treas- urer. BOARD OF TRUSTEES: Eric L. Goldstein, Irwin Lachoff, Phyllis Leffler, Stuart Rockoff, Robert N. Rosen, Betsy Blumberg Teplis. EX-OFFICIO: Hollace Ava Weiner, Jay Tanenbaum. Correspondence concerning author’s guidelines, contributions, and all edi- torial matters should be addressed to the Editor, Southern Jewish History, 2517 Hartford Dr., Ellenwood, GA 30294; email: [email protected]. The journal is interested in unpublished articles pertaining to the Jewish experience in the American South. For journal subscriptions and advertising, write Rachel B. Heimovics, SJH managing editor, 954 Stonewood Lane, Maitland, FL 32751; email: [email protected]; or visit www.jewishsouth.org. Articles appearing in Southern Jewish History are abstracted and/or indexed in Historical Abstracts, America: History and Life, Index to Jewish Periodicals, Journal of American History, and Journal of Southern History. -

The Story of Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim of Charleston, SC

The Story of Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim of Charleston, SC Congregation Founded 1749 Religious School Founded 1838 Present Sanctuary Built 1840 A National Historic Landmark of the United States The Oldest Synagogue in continuous use in the United States Founding Reform Jewish Congregation in the United States www.kkbe.org 2 Beginnings The story of Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim (KKBE) is one of faith, devotion, and perseverance in the American tradition of freedom of worship. Charleston was established in 1670; the earliest known reference to a Jew in the English settlement was in 1695. Soon other, primarily Sephardic, Jews followed, attracted by the civil and religious liberty of South Carolina. By 1749, these pioneers were sufficiently numerous to organize our congregation, Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim (Holy Congregation House of God). Fifteen years later, they also 1794 Synagogue before fire in 1838 established the now historic Coming Street Cemetery, the South’s oldest remaining colonial Jewish burial site. At first congregants worshipped in private homes; in 1780 they used an improvised synagogue adjacent to the present Temple grounds. In 1794 they dedicated a new synagogue building described then as the largest in the United States, “spacious and elegant” which signified the high degree of social acceptance Charleston Jews enjoyed. This handsome, cupolated Georgian synagogue was destroyed in the great Charleston fire of 1838 and replaced in 1840 on the same Hasell Street site by the present imposing structure. The Interior before 1838 fire by colonnaded Temple, dedicated in early 1841, is Solomon Nunez Carvalho renowned as one of the country’s finest examples of Greek Revival architecture. -

Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim: Rich Archival History Deserves Preservation

Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim: Rich Archival History Deserves Preservation www.kkbe.org for more information Contributors: Kate Fortney and Brenda Braye Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim (KKBE) in Charleston, South Carolina, is the oldest synagogue in continuous use in the United States. Its story is one of faith, perseverance, and tolerance in the American tradition of religious freedom. Charleston was established in 1670 and the earliest known reference to a Jew in the English settlement was in 1695. Attracted by the area’s civil and religious freedom, Jewish settlement continued to grow. By 1749, the pioneers living in this dynamic city were sufficiently numerous to organize KKBE. Fifteen years after KKBE was established, the congregation also established the Coming Street Cemetery, listed in the National Register of Historic Places as the oldest and largest colonial Jewish cemetery in the South. Coming Street Cemetery Long before there were distinctions between Orthodox, Conservative and Reform congregations, Coming Street was the cemetery for all of Charleston’s most distinguished Jewish families. It contains over 500 graves, some unmarked. The oldest identifiable grave is that of Moses D. Cohen, the first ritual leader of Congregation Beth Elohim, who died in 1762. The chief fascination of the Coming Street Cemetery is its rich archival legacy. Much of the history of one of the oldest Jewish communities in the United States and the contribution of Jews to South Carolina and America, can be deduced from these important records. Among those buried in the cemetery are 12 KKBE members who fought in the American Revolution, six soldiers of the War of 1812, two from the Seminole Wars in Florida, 23 Civil War participants, of whom eight died in the Confederate cause, six rabbis of the congregation, and 18 past presidents of the congregation. -

Fall 2020 Newsletter

YASCHIK/ARNOLD JEWISH STUDIES PROGRAM NEWSLETTER FALL 2020 We will bring more Jewish students to Charleston, in part by creating more scholarship opportunities. Offer more spiritual, intellectual, and social FROM THE DIRECTOR opportunities than ever before. Build a world-class Holocaust Studies Center. And transform our Arnold Center for Israel Studies into a What a year it has been! Our Program has gone campus-wide innovation and creativity hub. The Perlmutter Fellows through tremendous change, some by design, Program, now in its second year, will continue to bring the a lot by chance. Four people have left our team: Dr. brightest minds to CofC; it will soon become a nationally leading David Slucki, who took a position at Monash mentorship program. We are also in the midst of updating our University, in Australia; Dr. Ted Rosengarten, who curriculum and improving our marketing strategy. We know Jewish has retired; Pamela Partridge, who moved on after Studies is the best second major or minor students can choose. More serving as Hillel’s Engagement Coordinator and and more of them will soon realize it too. We will serve our community Associate Director for the last three years; and Mark better, as we engage with more facets of the Jewish experience. All this Swick, who for the last eight years worked as our will come. program’s Jewish community liaison, and is now the Executive Director at KKBE. We are thankful for their Thanks to our community’s ongoing support, we have managed service to our Program and wish them all the best. to weather this crisis well. -

David Lopez Jr.: Builder, Industrialist, and Defender of the Confederacy Barry Stiefel David Lopez Jr

David Lopez Jr.: Builder, Industrialist, and Defender of the Confederacy Barry Stiefel David Lopez Jr. (1809–1884), a pillar of Charleston’s Jewish community dur- ing the mid nineteenth century, was a prominent builder in an age when Jews had not yet ventured into the building trades. In addition to residences, commercial and public buildings, and even churches, Lopez’s building credits include Institute Hall, where the Ordinance of Secession was signed in 1860. Lopez also served as South Carolina’s general superintendent of state works during the “War Between Figure 1: Portrait of David Lopez, Jr. the States,” as he would have called it. His (Courtesy Special Collections, College of most noteworthy accomplishment from Charleston Library) the perspective of Jewish history was the construction of Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim (KKBE) in 1839–1841, the first synagogue built by a practicing Jew in the Americas. Throughout his adult life, Lopez lived and worked in the midst of a deeply divided Jewish community, where early reformers struggled against traditionalists to define what American Jewish identity should be. He too became engrossed within the conflict. His KKBE served as a stage on which the drama of the reformer-traditionalist clash took place. The life story of this extraordinary Jew, builder, and Confederate that thoroughly investigates the primary sources—separating fact from the accumulated myths in the handful of secondary sources that mention him—has yet to be written. His merchant (half) great-uncle, Aaron Lopez (1731–1782) of Newport, Rhode Island, has so far been the primary focus of this prolific family. -

Built for This Moment

BUILT FOR THIS MOMENT 2020 ANNUAL IMPACT REPORT OUR MISSION Board of Directors Executive Committee TO BUILD, SECURE, Ava Kleinman, President AND SUSTAIN JEWISH Eileen Chepenik, Immediate Past President Ilene Turbow, President Elect LIFE IN CHARLESTON, Michael Mills, Vice President Hilary Rieck, Vice President IN ISRAEL, AND Sharon Hox, Vice President Elliott Lessen, Secretary AROUND THE WORLD. Brian Shulman, Treasurer Terry Fisher, Jewish Endowment Foundation President Board Members at Large David Beckmann, Ellen Hoffman, Kapri Kreps CJF fulfills our mission by providing Rhodes, Ellen Hoffman, Rachel Landis, Abigail resources that strategically align with Leibowitz, Joshua Reeves, Joann Sherman, our core priorities: Shara Star, Ijo Toporek Professional Team Cultivating Jewish Life, Culture, & Education Judi Corsaro, Chief Executive Officer [email protected] Enhancing and Deepening our Community’s Commitment to Jewish Jason Roebuck, SCN Regional Security Philanthropy Advisor, [email protected] Strengthening our Connection to Israel Rebecca Engel, Chief Development Officer and Jewish Peoplehood [email protected] Creating a Community of Shared Erin Boynton, Chief Impact Officer Responsibility: Vulnerable Populations [email protected] Engaging the Next Generation in Jewish Brandon Fish, Director of JCRC, Life: Engagement and Leadership [email protected] Development Natanya Miller, Director of Educational Securing our Jewish Institutions and Initiatives [email protected] Community, -

The Wandering Jews Travel Program

THE WANDERING JEWS TRAVEL PROGRAM San Antonio Jewish Senior Services (SAJSS) has created a new travel program that gives groups of seniors the opportunity to experience elements of Jewish cultural, religious and/or historic content from around the world. Jews have a history of TWO TRAVEL OPPORTUNITIES AVAILABLE DURING 2018: wandering, whether in AUGUST 2018 the desert for 40 years DANUBE JEWISH DISCOVERY RIVER CRUISE or during 2,000 years of diaspora. Therefore, it seems only right that San Antonio Jewish seniors pick up the AUGUST 12 THROUGH AUGUST 24, 2018 This European river cruise starts with two nights in Budapest. THERE’S suitcase, so to speak, Sail along the Danube River with stops in Austria and Germany, ONLY ONE ending with three nights in Prague.. You’ll visit sites focusing on SAILING and hit the road. Jewish heritage and culture in Budapest, Vienna, Regensburg, and Prague, as well as a visit to the former concentration camp OF THIS RIVER CRUISE JUST BOOK, RELAX at Terezin. Throughout, you will be joined by a renowned expert on Jewish heritage who will present thought-provoking lectures PER YEAR! & THEN PACK! and answer your questions. Planning vacations can be stressful. But with these OCTOBER OR NOVEMBER 2018 trips, all logistics and special CHARLESTON, SOUTH CAROLINA excursion opportunities DATES TO BE DETERMINED for each of these trips will be A long weekend to Charleston, South Carolina, which has had handled by Spoil Me Rotten a vibrant Jewish community since before the Revolutionary War. Travel, with principals Charleston has many pieces of Jewish culture and history to experience: the oldest continuously Tina Dinesman Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim - run synagogue in the United States. -

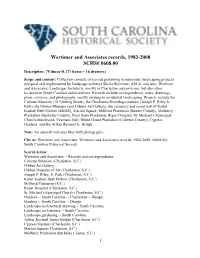

Wertimer and Associates Records, 0608.00

Wertimer and Associates records, 1982-2008 SCHS# 0608.00 Description: 75 linear ft. (71 boxes + 16 drawers) Scope and content: Collection consists of records pertaining to numerous landscaping projects designed and implemented by landscape architect Sheila Wertimer, ASLA, and later, Wertimer and Associates, Landscape Architects, mostly in Charleston and environs, but also other locations in South Carolina and elsewhere. Records include correspondence, notes, drawings, plans, invoices, and photographs, mostly relating to residential landscaping. Projects include the Calhoun Mansion (16 Meeting Street), the Charleston Riverdogs stadium (Joseph P. Riley Jr. Park), the Gibbes Museum (and Gibbes Art Gallery), the cemetery and social hall of Kadal Kadosh Beth Elohim (KKBE), Marion Square, Millford Plantation (Sumter County), Mulberry Plantation (Berkeley County), Poco Sabo Plantation, Roper Hospital, St. Michael’s Episcopal Church churchyard, Yeamans Hall, White House Plantation (Colleton County), Cypress Gardens, and the Arthur Ravenel Jr. Bridge. Note: An asterisk indicates files with photographs. Cite as: Wertimer and Associates. Wertimer and Associates records, 1982-2008. (0608.00) South Carolina Historical Society. Search terms: Wertimer and Associates -- Records and correspondence. Calhoun Mansion (Charleston, S.C.) Gibbes Art Gallery. Gibbes Museum of Art (Charleston, S.C.) Joseph P. Riley, Jr. Park (Charleston, S.C.) Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim (Charleston, S.C.) Millford Plantation (S.C.) Roper Hospital (Charleston, S.C.) St. Michael's -

Charleston (SC) Wiki Book 1 Contents

Charleston (SC) wiki book 1 Contents 1 Charleston, South Carolina 1 1.1 History ................................................. 2 1.1.1 Colonial era (1670–1786) ................................... 2 1.1.2 American Revolution (1776–1783) .............................. 3 1.1.3 Antebellum era (1785–1861) ................................. 4 1.1.4 Civil War (1861–1865) .................................... 5 1.1.5 Postbellum era (1865–1945) ................................. 5 1.1.6 Contemporary era (1944–present) .............................. 6 1.2 Culture ................................................ 7 1.2.1 Dialect ............................................ 7 1.2.2 Religion ............................................ 7 1.2.3 Annual cultural events and fairs ................................ 7 1.2.4 Music ............................................. 8 1.2.5 Live theatre .......................................... 8 1.2.6 Museums, historical sites and other attractions ........................ 8 1.2.7 Sports ............................................. 10 1.2.8 Fiction ............................................ 10 1.3 Geography ............................................... 11 1.3.1 Topography .......................................... 11 1.3.2 Climate ............................................ 12 1.3.3 Metropolitan Statistical Area ................................. 12 1.4 Demographics ............................................. 12 1.5 Government .............................................. 12 1.6 Emergency services ......................................... -

This Guide Has Been Created to Assist Researchers In

A GUIDE TO CHARLESTON AREA ARCHIVES, LIBRARIES AND MUSEUMS “More than forty miles of shelves…” by Donald Macbeth, ca. 1906 Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Online Catalog http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2014650185/ 5th Edition 2015 CALM Directory 2015 The Charleston Archives, Libraries and Museums Council (CALM) was organized in 1985 with the goal to start cooperative disaster preparedness planning. David Moltke-Hansen (at that time Director of the South Carolina Historical Society) coordinated 22 local cultural organizations into a group that could provide mutual assistance after storms or other disasters. The organization helped foster communication, local efforts of recovery, sharing of resources and expertise. CALM helped agencies, organizations, and institutions write disaster plans; sponsored workshops; and in general, raised consciousness about preservation and disaster preparedness and recovery needs. The statewide Palmetto Archives, Libraries and Museums Council on Preservation (PALMCOP) was then formed in Columbia in 1986 based on the successful model of CALM. CALM now provides an opportunity for participants in the archives, library, museum and records communities to interact in a supportive environment for the exchange of ideas and information. In 2001, CALM members created the Guide to Charleston Area Archives, Libraries and Museums to assist librarians, archivists, curators, and records managers in knowing “who has what,” and also to assist local researchers and scholars in their educational and academic pursuits. It was updated in 2004, 2008, and 2011, however, significant staffing and other changes have occurred in the last four years and this 5th edition reflects those changes. Institutions were contacted and asked to update their information sheets and most responded; however, for those that did not resond, the information from past updates and/or the institution’s website has been included. -

Peninsula Charleston ©2020 Explore Charleston

H A To North Charleston, R To Magnolia Cemetery M U Summerville M T JENKINS AVE. L O CLEVELAND ST. E J N D 26 O D G ST. Hampton Park VERICK N MA E K A E The A I V N S V E Citadel G A . E V A . S RTHU E R R. T RA Y D . V . 6 RRA EN ARY MU TRIE ST. HUGER ST. EL M L M J US MO M R. U B P P R K . To 17 North – T E I A S D E T R O R E H G G VE. E HU A H E R E LE L E E Mt. Pleasant, N A R - M K E H S T A G W I R R L W I S Y Isle of Palms, D I STUART ST. O W M . L N W I 1 O . E T 7 A S S O ER O G Sullivan’s Island O N U G S E O O H . N Y LN D RR R BE T O W R D A D STR N T A S D I H A A T. V T S S T C D ES V V R A . E G A ON . JOHNSON ST. C A E J E R V K . V O . E . E I S . N H . T G N 41 . S ST. E W . P S O SS ST C HARRIS ST. RE T H NG R E ST. N O AC O A N To Boone Hall C R .