A30 Chiverton to Carland Cross Environmental Statement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Penwhine, Trevarren, St. Columb, TR9 6PJ £345,000

• Delightful Detached Cottage Penwhine, Trevarren, St. Columb, TR9 6PJ £345,000 Sympathetically Updated & Nestling within this rural tranquil setting within the quiet hamlet of Trevarren is this delightful detached cottage which has been Refurbished sympathetically updated and refurbished by the current vendors and boasts double glazing and a oil fired central heating system. The cottage is approached by its own private driveway and there is ample parking. Entrance porch, living room, kitchen/diner, ut ility • Three Bedrooms room, cloakroom, three bedrooms and bathroom. Externally the property has a garage and the rear garden has a good degree of • Rear Garden and Garage privacy with the benefit of the afternoon and evening sun. This private cottage really does need to be viewed internally to appreciate the high specification and the standard of the works carried out and the overall charm of the cottage. Property Description Nestling within this rural tranquil setting within the quiet hamlet of Trevarren is this delightful detached cottage which has been sympathetically updated and refurbished by the current vendors and boasts double glazing, and oil fired central heating. The cottage is approached by its own private driveway and there is ample parking to the front, there is an entrance porch providing access to the living room with its fireplace housing log burner and clome oven, there is a beamed ceiling and stairs to the first floor and access into the kitchen/diner. The kitchen/dining room has been fully refurbished and again has a feature stone fireplace with clome oven, solid oak worktops and a range of base and wall units, integrated dishwasher, space for fridge/freezer and electric range. -

![CORNWALL.] FAR 946 ( L,OST OFFICE FARMERB Continued](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3089/cornwall-far-946-l-ost-office-farmerb-continued-403089.webp)

CORNWALL.] FAR 946 ( L,OST OFFICE FARMERB Continued

[CORNWALL.] FAR 946 ( l,OST OFFICE FARMERB continued. Kittow John, Higher Penrest, Lezant, Laity William, Tregartha, St. Hilary, Kempe Jas. Rosemanowas,St.Stythians Launceston Marazion Kempe John, Trolvis, St. Stytbians Kittow Jonathan, St. Clether, Launcstn Laity W.Tregiffian, St.Buryan,Penznce Kempthorne Charles, Carythenack, Kittow R. W estcot, Tremaine, Launcstn Laity W. Trerose, Mawnan, Falmouth Constantine, Penryn Kittow T.Browda,Linkinhorne,Callngtn Lake Daniel, Trevalis, St. Stythians Kempthorne James, Chenhall, Mawnan, Kittow Thomas, Tremaine, Launceston Lamb William & Charles, Butler's Falmouth KittowT. Uphill, Linkinhorne,Callingtn tenement, Lanteglos-by-Fowey,Fowy Kempthorne J. Park, Illogan,Camborne Kittow W. Trusell, Tremaine,Launcestn Lamb Charles, Lower Langdon, St. Kendall Mrs. Edwd. Treworyan, Probus KneeboneC.Polgear,Carnmenellis,Rdrth Neot, Liskeard Kendall J. Honeycombs, St.Allen,Truro Kneebone Joseph, Manuals, St. Columb Lamb H. Tredethy, St. Mabyn, Bodmin Kendall Richard, Zelah, St.Allen,Truro Minor Lamb J .Tencreek, St.Veep, Lostwithiel Kendall Roger, Trevarren, St. Mawgan, KneeboneRichard, Hendra, St. Columb Lambrick J.Lesneage,St.Keverne,Hlstn St. Columb Minor Lambrick John, Roskruge,St.Anthony- Kendall SilasFrancis,Treworyan, Probus Knee bone T. Reginnis,St. Paul,Penzance in-M eneage, Helston Kendall Thoma..'l, Greenwith common, Kneebone Thos. South downs, Redruth Lamerton Wm. Botus Fleming, Hatt Perran-arworthal Kneebone W. Gwavas,St.Paul,Penzance Laming Whitsed, Lelant, Hay le KendallThomas,Trevarren,St.Mawgan, Knight James, Higher Menadue, Lux- Lampshire W.Penglaze, St.Alleu,Truro St. Columb ulyan, Bodmin Lander C. Tomrose, Blisland, Bodmin Kendall 'Villiam, Bodrugan, Gorran Knight J. Rosewarrick,Lanivet,Bodmin Lander C. Skews, St. Wenn, Bodmin Kendall William, Caskean, Probus Knight }Jrs. J .Trelill,St.Kew, Wadebrdg Lander J. -

CORNWALL Extracted from the Database of the Milestone Society

Entries in red - require a photograph CORNWALL Extracted from the database of the Milestone Society National ID Grid Reference Road No Parish Location Position CW_BFST16 SS 26245 16619 A39 MORWENSTOW Woolley, just S of Bradworthy turn low down on verge between two turns of staggered crossroads CW_BFST17 SS 25545 15308 A39 MORWENSTOW Crimp just S of staggered crossroads, against a low Cornish hedge CW_BFST18 SS 25687 13762 A39 KILKHAMPTON N of Stursdon Cross set back against Cornish hedge CW_BFST19 SS 26016 12222 A39 KILKHAMPTON Taylors Cross, N of Kilkhampton in lay-by in front of bungalow CW_BFST20 SS 25072 10944 A39 KILKHAMPTON just S of 30mph sign in bank, in front of modern house CW_BFST21 SS 24287 09609 A39 KILKHAMPTON Barnacott, lay-by (the old road) leaning to left at 45 degrees CW_BFST22 SS 23641 08203 UC road STRATTON Bush, cutting on old road over Hunthill set into bank on climb CW_BLBM02 SX 10301 70462 A30 CARDINHAM Cardinham Downs, Blisland jct, eastbound carriageway on the verge CW_BMBL02 SX 09143 69785 UC road HELLAND Racecourse Downs, S of Norton Cottage drive on opp side on bank CW_BMBL03 SX 08838 71505 UC road HELLAND Coldrenick, on bank in front of ditch difficult to read, no paint CW_BMBL04 SX 08963 72960 UC road BLISLAND opp. Tresarrett hamlet sign against bank. Covered in ivy (2003) CW_BMCM03 SX 04657 70474 B3266 EGLOSHAYLE 100m N of Higher Lodge on bend, in bank CW_BMCM04 SX 05520 71655 B3266 ST MABYN Hellandbridge turning on the verge by sign CW_BMCM06 SX 06595 74538 B3266 ST TUDY 210 m SW of Bravery on the verge CW_BMCM06b SX 06478 74707 UC road ST TUDY Tresquare, 220m W of Bravery, on climb, S of bend and T junction on the verge CW_BMCM07 SX 0727 7592 B3266 ST TUDY on crossroads near Tregooden; 400m NE of Tregooden opp. -

11 Plymouth to Bodmin Parkway Via Dobwalls | Liskeard | Tideford | Landrake | Saltash

11 Plymouth to Bodmin Parkway via Dobwalls | Liskeard | Tideford | Landrake | Saltash COVID 19 Mondays to Saturdays Route 11 towards Bodmin Route 11 towards Plymouth Plymouth Royal Parade (A7) 0835 1035 1235 1435 1635 1835 1935 Bodmin Parkway Station 1010 1210 1410 1610 1810 2010 Railway Station Saltash Road 0839 1039 1239 1439 1639 1839 1939 Trago Mills 1020 1220 1420 1620 Milehouse Alma Road 0842 1042 1242 1442 1642 1842 1942 Dobwalls Methodist Church 1027 1227 1427 1627 1823 2023 St Budeaux Square [S1] 0850 1050 1250 1450 1650 1849 1949 Liskeard Lloyds Bank 0740 0840 1040 1240 1440 1640 1840 2032 Saltash Fore Street 0855 1055 1255 1455 1655 1854 1954 Liskeard Dental Centre 0741 0841 1041 1241 1441 1641 1841 Callington Road shops 0858 1058 1258 1458 1658 1857 1957 Liskeard Charter Way Morrisons 0744 0844 1044 1244 1444 1644 1844 Burraton Plough Green 0900 1100 1300 1500 1700 1859 1959 Lower Clicker Hayloft 0748 0848 1048 1248 1448 1648 1848 Landrake footbridge 0905 1105 1305 1505 1705 1904 2004 Trerulefoot Garage 0751 0851 1051 1251 1451 1651 1851 Tideford Quay Road 0908 1108 1308 1508 1708 1907 2007 Tideford Brick Shelter 0754 0854 1054 1254 1454 1654 1854 Trerulefoot Garage 0911 1111 1311 1511 1712 1910 2010 Landrake footbridge 0757 0857 1057 1257 1457 1657 1857 Lower Clicker Hayloft 0914 1114 1314 1514 1715 1913 2013 Burraton Ploughboy 0802 0902 1102 1302 1502 1702 1902 Liskeard Charter Way Morrisons 0919 1119 1319 1519 1720 1918 2018 Callington Road shops 0804 0904 1104 1304 1504 1704 1904 Liskeard Dental Centre 0921 1121 1321 1521 -

Cornwall Visitor Guide for Dog Owners

Lost Dogs www.visitcornwall.com FREE GUIDE If you have lost your dog please contact the appropriate local Dog Warden/District Council as soon as possible. All dogs are required by law to wear a dog collar and tag Cornwall Visitor bearing the name and address of the owner. If you are on holiday it is wise to have a temporary tag with your holiday address on it. Guide for NORTH CORNWALL KERRIER Dog Warden Service Dog Welfare and Dog Owners North Cornwall District Council Enforcement Officer Trevanion Road Kerrier District Council Wadebridge · PL27 7NU Council Offices Tel: (01208) 893407 Dolcoath Avenue www.ncdc.gov.uk Camborne · TR14 8SX Tel: (01209) 614000 CARADON www.kerrier.gov.uk Environmental Services (animals) CARRICK Caradon District Council Lost Dogs - Luxstowe House Dog Warden Service Liskeard · PL14 3DZ Carrick District Council Tel: (01579) 345439 Carrick House www.caradon.gov.uk Pydar Street Truro · TR1 1EB RESTORMEL Tel: (01872) 224400 Lost Dogs www.carrick.gov.uk Tregongeeves St Austell · PL26 7DS PENWITH Tel: (01726) 223311 Dog Watch and www.restormel.gov.uk Welfare Officer Penwith District Council St Clare Penzance · TR18 3QW Tel: (01736) 336616 www.penwith.gov.uk Further Information If you would like further information on Cornwall and dog friendly establishments please contact VisitCornwall on (01872) 322900 or e-mail [email protected] alternatively visit www.visitcornwall.com Welcome to the Cornwall Visitor Guide for Dog Welfare Dog Owners, here to help you explore Cornwall’s beaches, gardens and attractions with all the Please remember that in hot weather beaches may not be family including four legged members. -

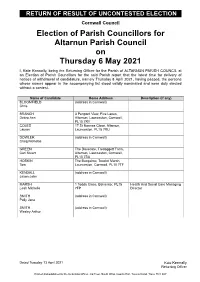

Election of Parish Councillors for Altarnun Parish Council on Thursday 6 May 2021

RETURN OF RESULT OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Cornwall Council Election of Parish Councillors for Altarnun Parish Council on Thursday 6 May 2021 I, Kate Kennally, being the Returning Officer for the Parish of ALTARNUN PARISH COUNCIL at an Election of Parish Councillors for the said Parish report that the latest time for delivery of notices of withdrawal of candidature, namely Thursday 8 April 2021, having passed, the persons whose names appear in the accompanying list stood validly nominated and were duly elected without a contest. Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) BLOOMFIELD (address in Cornwall) Chris BRANCH 3 Penpont View, Five Lanes, Debra Ann Altarnun, Launceston, Cornwall, PL15 7RY COLES 17 St Nonnas Close, Altarnun, Lauren Launceston, PL15 7RU DOWLER (address in Cornwall) Craig Nicholas GREEN The Dovecote, Tredoggett Farm, Carl Stuart Altarnun, Launceston, Cornwall, PL15 7SA HOSKIN The Bungalow, Trewint Marsh, Tom Launceston, Cornwall, PL15 7TF KENDALL (address in Cornwall) Jason John MARSH 1 Todda Close, Bolventor, PL15 Health And Social Care Managing Leah Michelle 7FP Director SMITH (address in Cornwall) Polly Jane SMITH (address in Cornwall) Wesley Arthur Dated Tuesday 13 April 2021 Kate Kennally Returning Officer Printed and published by the Returning Officer, 3rd Floor, South Wing, County Hall, Treyew Road, Truro, TR1 3AY RETURN OF RESULT OF UNCONTESTED ELECTION Cornwall Council Election of Parish Councillors for Antony Parish Council on Thursday 6 May 2021 I, Kate Kennally, being the Returning Officer for the Parish of ANTONY PARISH COUNCIL at an Election of Parish Councillors for the said Parish report that the latest time for delivery of notices of withdrawal of candidature, namely Thursday 8 April 2021, having passed, the persons whose names appear in the accompanying list stood validly nominated and were duly elected without a contest. -

Gardens Guide

Gardens of Cornwall map inside 2015 & 2016 Cornwall gardens guide www.visitcornwall.com Gardens Of Cornwall Antony Woodland Garden Eden Project Guide dogs only. Approximately 100 acres of woodland Described as the Eighth Wonder of the World, the garden adjoining the Lynher Estuary. National Eden Project is a spectacular global garden with collection of camellia japonica, numerous wild over a million plants from around the World in flowers and birds in a glorious setting. two climatic Biomes, featuring the largest rainforest Woodland Garden Office, Antony Estate, Torpoint PL11 3AB in captivity and stunning outdoor gardens. Enquiries 01752 814355 Bodelva, St Austell PL24 2SG Email [email protected] Enquiries 01726 811911 Web www.antonywoodlandgarden.com Email [email protected] Open 1 Mar–31 Oct, Tue-Thurs, Sat & Sun, 11am-5.30pm Web www.edenproject.com Admissions Adults: £5, Children under 5: free, Children under Open All year, closed Christmas Day and Mon/Tues 5 Jan-3 Feb 16: free, Pre-Arranged Groups: £5pp, Season Ticket: £25 2015 (inclusive). Please see website for details. Admission Adults: £23.50, Seniors: £18.50, Children under 5: free, Children 6-16: £13.50, Family Ticket: £68, Pre-Arranged Groups: £14.50 (adult). Up to 15% off when you book online at 1 H5 7 E5 www.edenproject.com Boconnoc Enys Gardens Restaurant - pre-book only coach parking by arrangement only Picturesque landscape with 20 acres of Within the 30 acre gardens lie the open meadow, woodland garden with pinetum and collection Parc Lye, where the Spring show of bluebells is of magnolias surrounded by magnificent trees. -

West Guide Web March 2021.Pdf

Download our app and purchase your tickets delivering services under the brand Transport for Cornwall today “Go Cornwall Bus” gocornwallbus.co.uk Find us on: gocornwallbus.co.uk [email protected] 0808 196 2632 Tickets purchased on the Go Cornwall Bus App are valid on Go Cornwall Bus, OTS, Hopley’s & Travel Cornwall services. Nationwide bus times 0871 200 22 33 calls cost 10p per minute from a BT landline calls from other service providers & mobiles may vary traveline.info All information correct at time of print 1 Welcome Welcome to your guide for Go Cornwall Bus services in West Cornwall. There are also guides available Did you know...? for Mid Cornwall & East Cornwall. You can also pick up a copy of our East & Mid Cornwall guides! Go Cornwall Bus partners with OTS, Hopley’s Coaces or visit our website www.gocornwallbus.co.uk & Travel Cornwall delivering services under the brand Transport for Cornwall. The new bus contract funded by Cornwall Council has enabled us to deliver over 100 new buses into service over the last 12 months. This has led to a step change in the quality of service provided & also supports Cornwall’s Climate Emergency. Buses operating under the Transport for Cornwall brand form the newest bus fleet in the country which helps us improve air quality. Where to find additional information Daily service updates are available on our Twitter feed & linked to our website at www.gocornwallbus.co.uk Longer term service disruptions, including road closures & diversions are also available on our Facebook page. Our App is available on both iOS & Android, allowing you to plan journeys, track live buses & buy tickets - just search for Go Cornwall Bus in the app store. -

![CORNWALL.] MAN 972 [POST OFFICE Maltsters-Continued](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0561/cornwall-man-972-post-office-maltsters-continued-1990561.webp)

CORNWALL.] MAN 972 [POST OFFICE Maltsters-Continued

[CORNWALL.] MAN 972 [POST OFFICE MALTSTERs-continued. MitcheH William & Son, Lelant, Hay le Bamfield James, Devoran Dawe John, Race hill, Launceston Mitchinson John, 9 Chapel st. Penzance; Barber Thomas, East Looe, Liskeard Dodd Mrs. Elizabeth, Broad st. Penryn & at Truro & St. Austell. See advt Barnes Thomas, ]0 Regentter.Penzance Dodd Mrs. E. College, Budock, Falmth Moreton William Moore, Coinage-hall Bamicoat Joseph, Fowey Ellis & Co. Church st. Helston. See ad vt street, Helston Barrett George, Bude GreenawayT. Marhamchurch, Stratton NankivellJohn Peter, Malpas rd. Truro Barrett Thomas, Rude GriggJhn. Church tn. St.ColumbMinor Norrington Charles & Co. Plymouth Bartlett John, West Looe, Liskeard Hart John, Treluswell & Ponsanooth, (Jsph.Thomas,agent), Treyew,Higher Bartlett Philip, West Looe, Liskeard St. Gluvias, Penryn town, Kenwyn, Truro Bate George, Bude Hicks Robert, Hallivick, St. Stephens· Orchard Wm. Western rd. Launceston Bate Thomas, Bude in-Branwell Parkyn Francis, Dobwalls, Liskeard Beal Richard, Fowey James William, Probus ParkynFrank,Lerryn,St.Veep,Lostwthl Beal William, Fowey Keast John, Little Petherick, St. Issey Pascoe Edward, Parade street; stores, Beens James, Polruan, Fowey Kendall Roger, Trevarren, St. Maw- Bread street, Penzance. See advt Bennett Cbas. H. 6 Draycot ter.St.lves gan, St. Columb Paynter J. BiPsoe chmicl.wks. Kea, Truro *Benney Richd. Boscawen bridge, Truro Kenner William, St. Issey Paynter J .Hicks mill,Gwennap,Scorrier Bowden Geo. jun. Porthleven, Helston Letcher & Hancock, Dirty Pool, St. Paynter J ohn,jun. Carnon, Kea, Truro Bray Alfred, Fowey Agnes, Scorrier Peter Richard,Penlaurel cottage, South Bridgman John, Bude Littleton J ames, North st. Lostwithiel Petherwin & TavistockBank,Launcstn Brokenshaw J ames, Fowey May John, Lanhem, St. -

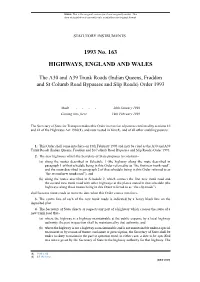

The A30 and A39 Trunk Roads (Indian Queens, Fraddon and St Columb Road Bypasses and Slip Roads) Order 1993

Status: This is the original version (as it was originally made). This item of legislation is currently only available in its original format. STATUTORY INSTRUMENTS 1993 No. 163 HIGHWAYS, ENGLAND AND WALES The A30 and A39 Trunk Roads (Indian Queens, Fraddon and St Columb Road Bypasses and Slip Roads) Order 1993 Made - - - - 26th January 1993 Coming into force - - 19th February 1993 The Secretary of State for Transport makes this Order in exercise of powers conferred by sections 10 and 41 of the Highways Act 1980(1), and now vested in him(2), and of all other enabling powers:– 1. This Order shall come into force on 19th February 1993 and may be cited as the A30 and A39 Trunk Roads (Indian Queens, Fraddon and St Columb Road Bypasses and Slip Roads) Order 1993. 2. The new highways which the Secretary of State proposes to construct– (a) along the routes described in Schedule 1 (the highway along the route described in paragraph 1 of that schedule being in this Order referred to as “the first new trunk road”, and the route described in paragraph 2 of that schedule being in this Order referred to as “the second new trunk road”), and (b) along the routes described in Schedule 2, which connect the first new trunk road and the second new trunk road with other highways at the places stated in that schedule (the highways along these routes being in this Order referred to as “the slip roads”), shall become trunk roads as from the date when this Order comes into force. -

The London Gazette, 13Th June 1986 7975

THE LONDON GAZETTE, 13TH JUNE 1986 7975 port, both in the county of Greater Manchester. Court . TRURO. No. of Matter—1 of 1984. Truste's' T^ame, -^STOCKPORT. No. of Matter—51 of 1984. Trustee's Address and Descrition—Official Receiver, 1st Floor, 63 Name, Address and Description—Official Receiver, Town- New George Street, Plymouth, Devon PL1 1RD; Date bury House, 11 Blackfriars. Street, Salford M3 SAB. of Release—2nd May 1986. -•"*; Date of Release—16th April 1986. COUTSOUBOS, Clifford Charles, of 32 Lodenek Avenue, HUDSON, John Henry, of Woodsmoor, Stockport, BUIL- Padstow, Cornwall, SHARE FISHERMAN, lately resid- DER and DECORATOR, carrying on business under ing at 5 High Street, Padstow, Cornwall, formerly re- the title of Hudsons Builders Plumbers and Decorating siding at 23 Alan Road, Padstow, Cornwall, previously Contractors at Station Approach, Edgeley Side, Stock- residing at Fore Street, Newlyn, Penzance, Cornwall. port. Court-nSTOCKPORT. No. of Matter—1 of 1978. Court—TRURO. No. of Matter-^lA of 1984. Trustee's Trustee's Name, Address and Description—Freeman, Name, Address and Description—Official Receiver, *lst John A., 8 Manchester Road, Bury, Greater Manchester, Floor, 63 New George Street, Plymouth, Devon. Date Chartered Accountant. Date of Release—1st May 1986. of Release—2nd' May 1986. MARSH, Christopher, Builder's labourer, of the Old Post HILL, Stephen Roger,"Computer Assistant, of 11 Corona- Office, Church Lane, Maclesfield, in the county of Che- tion Place> Helston, Cornwall TR13 4AD, lately trading shire, formerly residing at 113 Edgeby Road, Stockport, with others as " Whitegate (Redruth) " at 26 Green Lane, hi the metropolitan county of Greater Manchester, and Redruth, Cornwall as DOUBLE GLAZING & KITCHEN ' JONES, Martin John, Warehouseman, of 27 Park Place, CONTRACTORS. -

Cornwall. Sho 1459

TRAUES DIRECTORY.] CORNWALL. SHO 1459 "Rowe William, Splatt, Tresmere, Eglos- Spratt Geo. 31 & 32 New st. Penzance ThomasHenry,Portheras cross,Pendeen, kerry R.S.O . Stanley Mrs. Ann, 21 Tamar st. Saltash t5t. Just-in-Penwith Rowett Mrs. S.Marketst.LooeEastR.S.O Statton Mrs. Martha, Calstock Thomas I. Longstone, St. Mabyn R.S.O Rowland Thomas, Post office, Coppe- Steer Wm. 8 & 9 Tregolls road, Trnro Thomas Miss Jane, Fore street, St. thorne, Poundstock, Stratton R.S.O Stenlake Charles, Chilsworthy, Gunnis- Just-in-Penwith R.S.O Row ling J. Post office,Leeds town,Hayle lake, Tavistock Thomas Mrs. Jane,Cape Cornwall street, .Rowse William Henry, Trevarren, St. Stentiford Mrs. G. Gerrans, l<~almouth St. Just-in-Penwith R.S.O Columb. Major R.S.O Stepheos Chas. Higher Bore st. Bodmin Thomas Mrs. Jane, Helston rd. Penryn Rowter Mrs. Kate, Callington R.S.O StephensE.B.Latchley,Gunnslke.'fvstck Thomas Mrs. Jane, Polkirt street,Meva- RuberryWm.J.CanonsTwn.LelantR.S.O StephensMrs.E.Canons Tn.Lelant R.S.O gissey, St. Austell Rule Miss H. Condurrow, Camborne Stephens Fredk. 44 Chapel st. Penzanca Thomas Mrs. Jane, Treleigh, Redruth Rule John G. Trevenson st. Cam borne Stephens Jn. Manhey, Wendron, Helston Thomas John, Borrow rd. :::it. Ives R.S.O Rule Mrs.M.A.Post off.Troon,Cambrne Stephens John, I6 Old Bridge st. Truro Thomas John, Laity, Wendron, Helston Rundle Miss B. H. 5 Tamar st. Saltash Stephens Mrs. Mary Ann, White cross, Thomas John, Trethurgy, Treverbyn, Rundle Charles, Merther lane, Merther, Ludgvan, Long Rock R.S.O St.