CHRIS CUTLER Composition and Experimentation in British Rock

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE SHARED INFLUENCES and CHARACTERISTICS of JAZZ FUSION and PROGRESSIVE ROCK by JOSEPH BLUNK B.M.E., Illinois State University, 2014

COMMON GROUND: THE SHARED INFLUENCES AND CHARACTERISTICS OF JAZZ FUSION AND PROGRESSIVE ROCK by JOSEPH BLUNK B.M.E., Illinois State University, 2014 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master in Jazz Performance and Pedagogy Department of Music 2020 Abstract Blunk, Joseph Michael (M.M., Jazz Performance and Pedagogy) Common Ground: The Shared Influences and Characteristics of Jazz Fusion and Progressive Rock Thesis directed by Dr. John Gunther In the late 1960s through the 1970s, two new genres of music emerged: jazz fusion and progressive rock. Though typically thought of as two distinct styles, both share common influences and stylistic characteristics. This thesis examines the emergence of both genres, identifies stylistic traits and influences, and analyzes the artistic output of eight different groups: Return to Forever, Mahavishnu Orchestra, Miles Davis’s electric ensembles, Tony Williams Lifetime, Yes, King Crimson, Gentle Giant, and Soft Machine. Through qualitative listenings of each group’s musical output, comparisons between genres or groups focus on instances of one genre crossing over into the other. Though many examples of crossing over are identified, the examples used do not necessitate the creation of a new genre label, nor do they demonstrate the need for both genres to be combined into one. iii Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Part One: The Emergence of Jazz………………………………………………………….. 3 Part Two: The Emergence of Progressive………………………………………………….. 10 Part Three: Musical Crossings Between Jazz Fusion and Progressive Rock…………….... 16 Part Four: Conclusion, Genre Boundaries and Commonalities……………………………. 40 Bibliography………………………………………………………………………………. -

Here I Played with Various Rhythm Sections in Festivals, Concerts, Clubs, Film Scores, on Record Dates and So on - the List Is Too Long

MICHAEL MANTLER RECORDINGS COMMUNICATION FONTANA 881 011 THE JAZZ COMPOSER'S ORCHESTRA Steve Lacy (soprano saxophone) Jimmy Lyons (alto saxophone) Robin Kenyatta (alto saxophone) Ken Mcintyre (alto saxophone) Bob Carducci (tenor saxophone) Fred Pirtle (baritone saxophone) Mike Mantler (trumpet) Ray Codrington (trumpet) Roswell Rudd (trombone) Paul Bley (piano) Steve Swallow (bass) Kent Carter (bass) Barry Altschul (drums) recorded live, April 10, 1965, New York TITLES Day (Communications No.4) / Communications No.5 (album also includes Roast by Carla Bley) FROM THE ALBUM LINER NOTES The Jazz Composer's Orchestra was formed in the fall of 1964 in New York City as one of the eight groups of the Jazz Composer's Guild. Mike Mantler and Carla Bley, being the only two non-leader members of the Guild, had decided to organize an orchestra made up of musicians both inside and outside the Guild. This group, then known as the Jazz Composer's Guild Orchestra and consisting of eleven musicians, began rehearsals in the downtown loft of painter Mike Snow for its premiere performance at the Guild's Judson Hall series of concerts in December 1964. The orchestra, set up in a large circle in the center of the hall, played "Communications no.3" by Mike Mantler and "Roast" by Carla Bley. The concert was so successful musically that the leaders decided to continue to write for the group and to give performances at the Guild's new headquarters, a triangular studio on top of the Village Vanguard, called the Contemporary Center. In early March 1965 at the first of these concerts, which were presented in a workshop style, the group had been enlarged to fifteen musicians and the pieces played were "Radio" by Carla Bley and "Communications no.4" (subtitled "Day") by Mike Mantler. -

Blabla Bio Fred Frith

BlaBla Bio Fred Frith Multi-instrumentalist, composer, and improviser Fred Frith has been making noise of one kind or ano- ther for almost 50 years, starting with the iconic rock collective Henry Cow, which he co-founded with Tim Hodgkinson in 1968. Fred is best known as a pioneering electric guitarist and improviser, song-writer, and composer for film, dance and theater. Through bands like Art Bears, Massacre, Skeleton Crew, Keep the Dog, the Fred Frith Guitar Quartet and Cosa Brava, he has stayed close to his roots in rock and folk music while branching out in many other directions. His compositions have been performed by ensembles ranging from Arditti Quartet and the Ensemble Modern to Concerto Köln and Galax Quartet, from the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra to ROVA and Arte Sax Quartets, from rock bands Sleepytime Gorilla Museum and Ground Zero to the Glasgow Improvisers’ Orchestra. Film music credits include the acclaimed documentaries Rivers and Tides, Touch the Sound and Leaning into the Wind, directed by Thomas Riedelsheimer, The Tango Lesson, Yes and The Party by Sally Potter, Werner Penzel’s Zen for Nothing, Peter Mettler’s Gods, Gambling and LSD, and the award-winning (and Oscar-nominated) Last Day of Freedom, by Nomi Talisman and Dee Hibbert- Jones. Composing for dance throughout his long career, Fred has worked with Rosalind Newman and Bebe Miller in New York, François Verret and Catherine Diverrès in France, and Amanda Miller and the Pretty Ugly Dance Company over the course of many years in Germany, as well as composing for two documentary films on the work of Anna Halprin. -

Jason Jägel La Machine Molle February 7 - March 27, 2020 Opening Reception Friday February 7, 6-9Pm

JASON JÄGEL LA MACHINE MOLLE FEBRUARY 7 - MARCH 27, 2020 OPENING RECEPTION FRIDAY FEBRUARY 7, 6-9PM Gallery 16 is pleased to welcome artist Jason Jägel for his second solo exhibition with the gallery, La Machine Molle. Jägel presents a new series of paintings, works on paper and sculptures. There will be an opening reception for the artist on Friday, February 7th, from 6-9pm. La Machine Molle is French for The Soft Machine, the title of a 1961 cut-up novel by American author William S. Burroughs, as well as the name of seminal Canterbury scene band, Soft Machine. After being kicked out of his own band (Soft Machine), Robert Wyatt started a new band which he named Matching Mole, a linguistic pun on the French name for Soft Machine. The images in a new series of paintings refer to the 1972 live performance of Wyatt’s group on the French television program Rockenstock. Jägel broad admiration for Wyatt includes his use of everyday speech, wry humor, and self-referential elements in his lyrics. There is a kinship in the way both Jägel and Wyatt bring together elements of improvisation and lyrical narrative. In his own unique and poetic way, Jason Jägel's work cultivates a strong improvisational component, born out of a form of autobiographical fiction, his love of music, comics, and literary fiction. In the words of Kevin Killian, he is an “ace raconteur” and, above all, Jägel's work tells a story. His compositions often appear as fragments where experiences, dreams, people, places, individual narratives and past experiences intersect and intertwine to create open-ended, conversational stories full of rhythm and flow. -

Lindsay Cooper: Bassoonist with Henry Cow Advanced Search Article Archive Topics Who Who Went on to Write Film Music 100 NOW TRENDING

THE INDEPENDENT MONDAY 22 SEPTEMBER 2014 Apps eBooks ijobs Dating Shop Sign in Register NEWS VIDEO PEOPLE VOICES SPORT TECH LIFE PROPERTY ARTS + ENTS TRAVEL MONEY INDYBEST STUDENT OFFERS UK World Business People Science Environment Media Technology Education Images Obituaries Diary Corrections Newsletter Appeals News Obituaries Search The Independent Lindsay Cooper: Bassoonist with Henry Cow Advanced search Article archive Topics who who went on to write film music 100 NOW TRENDING 1 Schadenfreudegasm The u ltim ate lis t o f M an ch ester -JW j » United internet jokes a : "W z The meaning of life J§ according to Virginia Woolf 3 Labour's promises and their m h azard s * 4 The Seth Rogen North Korea . V; / film tra ile r yo u secretly w a n t to w atch 5 No, Qatar has not been stripped o f th e W orld Cup Most Shared Most Viewed Most Commented Rihanna 'nude photos' claims emerge on 4Chan as hacking scandal continues Frank Lampard equalises for Manchester City against Her Cold War song cycle ‘ Oh Moscow’ , written with Sally Potter, was performed Chelsea: how Twitter reacted round the world Stamford Hill council removes 'unacceptable' posters telling PIERRE PERRONE Friday 04 October 2013 women which side of the road to walk down # TWEET m SHARE Shares: 51 Kim Kardashian 'nude photos' leaked on 4chan weeks after Jennifer Lawrence scandal In the belated rush to celebrate the 40 th anniversary of Virgin Records there has been a tendency to forget the groundbreaking Hitler’s former food taster acts who were signed to Richard Branson’s label in the mid- reveals the horrors of the W olf s Lair 1970s. -

Sélection De La Commission Musique Nouvelle 40176 PCDM3 450 and 40177 PCDM3 450 CHA Voir PCDM4 Voir PCDM4 PCDM4 7 and CC PCDM4 7 CHA Gris Gris

Sélection de la commission Musique nouvelle 40176 PCDM3 450 AND 40177 PCDM3 450 CHA voir PCDM4 voir PCDM4 PCDM4 7 AND CC PCDM4 7 CHA Gris Gris 1CD Elektra WAR 1CD Tzadik ORK Anderson, Laurie Charming Hostess Homeland Bowls project (The) Laurie Anderson : voix, claviers J Eisenberg: voice, dulcimer, harmonium Eyvind Kang, Lou Reed, John Zorn, Antony, etc... Minimaliste Etats-Unis C Taylor: voice / J Ditzian: clarinets / s Ismaily: bass, perc, guit/ C Nouvel album de Laurie Anderson qui résume le spectacle Smith: drums + invités multimédia qu'elle fait tourner et évoluer depuis plusieurs rock chant west coast Amerique années. Elle n'avait pas sorti d'album en studio depuis "Life on a Chant rock décalé d'une charmante hôtesse qui passe de l'ange String" en 2001. au démon sans détour dans le registre vocal qui peut faire Ce nouvel opus est accompagné d'un DVD retraçant la genèse de penser à la chanteuse d'Art Bears. Des violons rock punk fusent, ce projet. les textes s'inspirent des inscriptions anciennes du babylon juif ; La musique et les textes sont quand à eux dignes du talent de les genres s'entremèlent mais restent mystiques sur des airs qui cette grande artiste-performeuse avec les mêmes composantes peuvent faire penser à la tradition celte ou à celle d'Afrique du que sur ses disques précédents : une musique minimaliste nord, on croise même des airs de bluegrass qui décoiffent ou accessible et sophistiquée, des textes mi-parlés mi-chantés, un baladent. Des percussions font envenimer ces univers insensés mélange d'influences qui vont de l'avant-garde new-yorkaise des et poétiques, des troubadours femmes avancent comme des annés 70-80 aux couleurs "world". -

Fred Frith (Filmmusik)

Fred Frith (Filmmusik) Geboren 1949 in Heathfield, East Sussex, England. Im Alter 5 Jahren begann Fred Frith mit dem Violinen-Spiel, später kamen das Klavierspiel, mit 13 Jahren die Gitarre hinzu. Während seines Studiums in Cambrige gründete er 1968 mit dem Saxophonisten Tim Hodgkinson die wegweisende Independent-Band Henry Cow, die u.a. mit Chris Cutler, John Greaves und Lindsay Cooper zusammen arbeitete. Nach der Auflösung von Henry Cow ging Frith 1979 nach New York, wo er mit Künst- lern der Downtown-Szene um Tom Cora, Bob Ostertag, Ikue Mori, John Zorn und anderen in Kontakt kam. Die Arbeit von Fred Frith ist seitdem ungewöhnlich vielfäl- tig. Er arbeitete u.a. zusammen mit Amy Denio, Brian Eno, Half Japanese, Material, The Residents, Robert Wyatt, Heiner Goebbels und Yo Yo Ma, produzierte Alben für The Orthotonics, David Moss, Tenko und V- Effec, war Bassist in John Zorns Band Naked City und gründete so unterschiedliche Formationen wie The Guitar Quartett, Massacre (mit Bill Laswell und Charles Hayward) und Skeleton Crew (mit Tom Cora und Zeena Parkins). "Nach mehr als 20 Jahren mit Aufnahmen und Perfor- mances ist Fred Frith so etwas wie die Ikone der Avant- garde Music geworden“ schrieb Die Zeit 1991. „Die Kri- tiker haben ihm Unrecht getan, indem sie ihn als impro- visierenden Cage-Jünger beschrieben... Bei der Anerken- nung der intellektuellen Aspekte seiner Musik dürfen aber nicht die unsterbliche Neugier, der bittere Witz, sein kindlicher Spieltrieb und die schleichende Melan- cholie übersehen werden." In den letzten Jahren verla- gerte sich der Schwerpunkt von Friths Arbeit von der Perfomance hin zur Komposition, dazu kamen zahlrei- che Arbeiten für Theater, Tanz, Film, Malerei und Video. -

View 2012 Program

INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR IMPROVISED MUSIC SIXTH FESTIVAL/CONFERENCE Improvisation · Self · Community·World February 16-19, 2012 William Paterson University Wayne, New Jersey, USA Keynote artists and performers: Pyeng Threadgill & trio Ikue Mori, Sylvie Courvoisier & Jim Black Mulgrew Miller WyldLyfe Robert Dick & Tom Buckner Karl Berger with the University of Michigan Creative Arts Orchestra And over 50 other artists presenting concerts, panels, talks and workshops! ISIM President’s Welcome ISIM President’s Welcome On behalf of the Board of Directors of the International Society for Improvised Music, I extend to all of you a hearty welcome to the sixth ISIM Festival/Conference. Nothing is more gratifying than gatherings of improvising musicians as our common process, regardless of surface differences in our creative expressions, unites us in ways that are truly unique. As the conference theme suggests, by going deep within our reservoir of creativity, we access subtle dimensions of self—or consciousness—that are the source of connections with not only our immediate communities but the world at large. It is dificult to imagine a moment in history when the need for this improvisation-driven, creativity revolution is greater on individual and collective scales than the present. Please join me in thanking the many individuals, far too many to list, who have been instrumental in making this event happen. Headliners Ikue Mori, Pyeng Threadgill, Wyldlife, Karl Berger, the University of Michigan Creative Arts Orchestra, the William Paterson University jazz group, Mulgrew Miller, Robert Dick, and Thomas Buckner—we could not have asked for a more varied and exciting line-up. ISIM Board members Stephen Nachmanovitch and Bill Johnson have provided invaluable assistance, with Steve working his usual heroics with the ISIM website in between, and sometimes during, his performing and speaking tours. -

Here to Be Objectively Apprehended

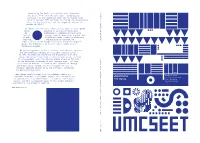

UMCSEET UNEARTHING THE MUSIC Creative Sound and Experimentation under European Totalitarianism 1957-1989 Foreword: “Did somebody say totalitarianism?” /// Pág. 04 “No Right Turn: Eastern Europe Revisited” Chris Bohn /// Pág. 10 “Looking back” by Chris Cutler /// Pág. 16 Russian electronic music: László Hortobágyi People and Instruments interview by Alexei Borisov Lucia Udvardyova /// Pág. 22 /// Pág. 32 Martin Machovec interview Anna Kukatova /// Pág. 46 “New tribalism against the new Man” by Daniel Muzyczuk /// Pág. 56 UMCSEET Creative Sound and Experimentation UNEARTHING THE MUSIC under European Totalitarianism 1957-1989 “Did 4 somebody say total- itarian- ism?” Foreword by Rui Pedro Dâmaso*1 Did somebody say “Totalitarianism”* Nietzsche famously (well, not that famously...) intuited the mechanisms of simplification and falsification that are operative at all our levels of dealing with reality – from the simplification and metaphorization through our senses in response to an excess of stimuli (visual, tactile, auditive, etc), to the flattening normalisation processes effected by language and reason through words and concepts which are not really much more than metaphors of metaphors. Words and concepts are common denominators and not – as we'd wish and believe to – precise representations of something that's there to be objectively apprehended. Did We do live through and with words though, and even if we realize their subjectivity and 5 relativity it is only just that we should pay the closest attention to them and try to use them knowingly – as we can reasonably acknowledge that the world at large does not adhere to Nietzsche’s insight - we do relate words to facts and to expressions of reality. -

Chris Cutler, Loops Analogiques, Digitales, À L'unisson, Déphasées, Multipistes, Échantillonnées Ou Improvisées. Les Usage

Culture, le magazine culturel en ligne de l'Université de Liège Chris Cutler, Loops Analogiques, digitales, à l'unisson, déphasées, multipistes, échantillonnées ou improvisées. Les usages que revêtent les boucles musicales sont multiples. Elles se déploient dans les studios d'enregistrement, envahissent les radios, tournent dans les supermarchés, ou accompagnent les jeux vidéo. On les a d'abord entendues chez Pierre Schaeffer et Karlheinz Stockhausen, ou peut-être avant dans les premiers synthétiseurs, voire en appelant les premières horloges parlantes. On les entendait surtout lorsque les disques se rayaient depuis le début du 19 e siècle. Elles ont conquis Steve Reich et Terry Riley, puis Brian Eno et Kraftwerk, Grandmaster Flash et Boards of Canada. Il était même des humains pour les imiter : Glenn Branca, Rhys Chatham avec leurs armées de guitares en premier. Boucles et répétitions semblent avoir bel et bien assujetti le monde à l'aube du 21 e siècle. C'est afin d'interroger les multiples usages et sens de la boucle et de distinguer cette structure des autres formes de répétition dans son rapport au temps et à l'espace qu'est né le projet « Understanding the Loop » sous les auspices du CIPA (Centre Interdisciplinaire de Poétique Appliquée). Ce projet prend également en considération de façon historique les techniques et spécificités historiques propres aux différentes formes d'art où on lui reconnaît un rôle prépondérant ; tout comme de rendre compte des manières distinctes de moduler la répétition qui dépassent le simple argument trop souvent avancé de la logique « non linéaire » qui serait mise en place par la boucle. -

Popular Music Studies in Italian Universities —A Petition—

Popular Music Studies in Italian Universities: a petition — signatories 1 Popular Music Studies in Italian Universities —a Petition— Final list: 573 signatories from 47 nations (2015‐06‐14, 15:37 hrs BST) Signatory numbers by nation state Argentina 12 Australia 23 Austria 5Belgium 2Brazil 56 Bulgaria 2 Canada 34 Chile 8 China 1 Colombia 7Croatia 1Cuba 2 Cyprus 1Denmark 6Estonia 5Finland 21 France 16 Germany 18 Greece 3Iceland 1Ireland 10 Israel 4Italy 77 Jamaica 1 Japan 1 Lithuania 1Mexico 3 Mozambique 1Netherlands 9New Zealand 4 Norway 7Peru 1 Poland 1Portugal 6Singapore 1Slovenia 2 South Africa 8South Korea 1Spain 33 Sweden 5Switzerland 2South Africa 8 Turkey 3Uganda 1UK 108 Uruguay 5USA 43 THE FOLLOWING IS A LIST OF SIGNATORIES IN ALPHABETICAL ORDER OF FAMILY NAME. •There is a basic list of signatories in alphabetical order of nation state at http://tagg.org/html/Petition1405/PetitionResidence.htm •The ACTUAL PETITION can be viewed in English, Italian or Spanish by visiting http://tagg.org/html/Petition1405.html. List of 573 signatories to the petition A 1. Silvia Irene ABALLAY — Profesor Titular, Universida Nacional de Villa María (Argentina) 2. Lauren ACTON — Course Director, Centennial College/York University, Toronto (Canada) 3. Roberto, AGOSTINI — Professore a contratto, Conservatori di Cesena e di Sassari, Bologna (Italy) 4. Coriún AHARONIÁN — Composer and former professor, Escuela Universitaria de Música, Universidad de la República; Director, Centro Nacional de Documentación Musical Lauro Ayestarán; Emeritus researcher, National System of Researchers (Uruguay) 5. Michael AHLERS — Professor for music education and popular music, Leuphana University of Lüneburg (Germany) 6. Kaj AHLSVED — PhD Candidate in Musicology, Åbo Akademi University, Turku (Finland) 7. -

Downbeat.Com September 2010 U.K. £3.50

downbeat.com downbeat.com september 2010 2010 september £3.50 U.K. DownBeat esperanza spalDing // Danilo pérez // al Di Meola // Billy ChilDs // artie shaw septeMBer 2010 SEPTEMBER 2010 � Volume 77 – Number 9 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Ed Enright Associate Editor Aaron Cohen Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Kelly Grosser AdVertisiNg sAles Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sue Mahal 630-941-2030 [email protected] offices 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] customer serVice 877-904-5299 [email protected] coNtributors Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough, Howard Mandel Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Michael Point; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, How- ard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Robert Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Jennifer