Narratives on Political and Constitutional Changes in Kashmir (1947-1990)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Article 370, Federalism and the Basic Structure of the Constitution

TIF - Article 370, Federalism and the Basic Structure of the Constitution FAIZAN MUSTAFA July 5, 2019 Photo credit: Saktishree DM | Flickr (CC BY-ND 2.0) Article 370 is a permanent and not temporary provision of the Constitution that assures Jammu and Kashmir autonomy. Its content may have been hollowed out but it remains important for the people of Kashmir. Calls to scrap it are based on a misinterpretation. The Article 370 debate is back centre-stage. The new Union Home Minister, Amit Shah, has made a detailed statement on Article 370 after his return from Kashmir. In tune with his party’s ideological position, he has yet again termed this constitutional provision as “temporary”. At the same time he has been candid enough to confess for the first time that most elections in Kashmir had been rigged. The importance of Article 370 to Kashmir and the significance it holds in our Constitution are issues that need to be constantly reiterated to dispel the considerable misinterpretation and misunderstanding about this provision in the Constitution of India History of Article 370 The most important feature of federalism in the United States of America (USA) was the ”compact” between the Page 1 www.TheIndiaForum.in July 5, 2019 erstwhile 13 British colonies that constituted themselves first into a confederation and then into a federal polity under the 1791 constitution of the USA. In a confederation units do have a right to secede, but in a federation they do not have such a right though in this system they are given a lot of autonomy to operate within their allotted spheres. -

Page1.Qxd (Page 2)

daily REGD. NO. JK-71/18-20 Vol No. 55 No. 20 JAMMU, SUNDAY, JANUARY 20, 2019 16+4 (Magazine) = 20 Pages ‘ 5.00 ExcelsiorRNI No. 28547/65 Oppn parties First-ever address to Kashmir Sarpanchs Fresh snowfall Officials’ panel fails to meet deadline for probe into IWMP liabilities join hands in Kashmir KOLKATA, Jan 19: Excelsior Correspondent After 26 yrs, Govt wakes up to conduct Leaders from over a dozen Modi to keep up tradition, opposition parties came togeth- SRINAGAR, Jan 19 : er today, vowing at a mega rally Kashmir valley today experi- here to put up a united fight in enced fresh snowfall, with the enquiry into embezzlement of funds the coming Lok Sabha elections visit all 3 regions on day’s tour Weatherman forecasting heavy Mohinder Verma and oust Prime Minister snowfall for next two days Enquiry Officer unaware of Narendra Modi from power. while the divisional administra- JAMMU, Jan 19: Over 20 leaders, including 4 projects declared as national: Dr Jitendra tion has issued an avalanche Incredible it may sound but it ground behind belated step two from the Congress, attend- warning. is a fact that Government has ment which had taken place ed the show of unity organised three regions via e-mode from emony of Ladakh University enquiry against the delinquent Sanjeev Pargal * Pic on page 6. initiated an enquiry into the nearly 26 years back has been by Trinamool Congress leader Vijaypur in Samba district of and extension of Leh Airport,'' officers/officials involved in Video on embezzlement of funds which misappropriation/embezzlement mentioned in the order. -

Forces Illegally Occupy 2710 Kanal Wakf Land in JK: Govt

SRINAGAR | June 9, 2016, Thursday THURSDAY, June 09, 2016 03, Ramadan , 1437 AH 29th Year of publication 02 Greater Kashmir epaper.GreaterKashmir.com facebook.com/DailyGreaterKashmir twitter.com/GreaterKashmir_ STATE No militant attack threat to Noisy scenes Sugar shortage, windstorm in LC over Amarnath Yatra: GOC Victor Force ‘embezzlement’ KHALID GUL Narola, however, when GOC, however, said that in Forest dept reminded about the state- the army was ready to face CAA/00383 damage echoes in Assembly Anantnag (Islamabad), ment from Director General any challenge. SYED RIZWAN GEELANI June 8: Day after Hizb com- BSF about the possibility of “We are committed to GK NEWS NETWORK Sugar available in Kash- shortage of sugar in Kash- the demand of compensa- mander conveyed in his militant attack on yatra said ensure smooth conduct of Srinagar, June 8: Noisy scenes Published from Srinagar | Jammu Regd. No. JKNP-5/SKGPO-2015-2017 Vol: 29 No. 161 Pages: 20 Rs. 5.00 GreaterKashmir.com, GreaterKashmir.net, GreaterKashmir.news epaper.GreaterKashmir.com mir. mir. tion for losses suffered in video message that Ama- the matter got cleared later yatra and are putting in were witnessed in the Upper Srinagar, June 8: “You should apologize The protesting law- Bandipora and Islamabad rnath Yatra was not their and there is nothing like place the same strategy as House on Wednesday after The State Government for misleading the House. makers also asked the districts due to Tuesday’s target, Army on Wednesday that. we have been in the past opposition MLC Dr Bashir Wednesday faced flak in We don’t know whether Minister to come up with windstorm. -

Epilogue Magazine, September 2008

Epilogue because there is more to know www.epilogue.in CONTENTS Prologue 3 Editor in Chief Letters to the editor 4 Zafar Choudhary Hear & Hear Consulting Editor Who Said What 5 D. Suba Chandran Columns Associate Editor Keen Eye 6 Irm Amin Baig Ladakh Designs & Layout Agriculture 44 Keshav Sharma Interview 47 Mailing Address Volume 2, Issue 9, September 2008 Diary 49 PO Box 50, HO Gandhi Nagar, Jammu IN FOCUS Stop Press Fire 2008 Review of Media 51 Phones & email Office : +91 191 2493136 Reviews Jammu And Kashmir Editorial: +91 94191 80762 9 Movies 53 Administration: +91 94190 00123 Beginning Of The Endgame [email protected] Post-Agitation 18 Epilogue [email protected] Uphill Task For Jammu’s Politics, Economy From the Consulting Editor 56 [email protected] 22 Amarnath Confrontation : Is It Sureal ? Edited, Printed & Published by 26 Replay Of 90’s ? Zafar Choudhary for CMRD Still No Lessons From History Publications and Communications Find The Enemy Published from ‘Ibadat’, Madrasa 28 ...It Is Communalism Lane, Bhatindi Top, Jammu, J&K 33 Our Mis-Leaders, 39 Hectares Printed at Of Land And Seesaw Of Faith Dee Dee Reprographix, Jammu 35 Jam-Kash Showdown Clash Of Vested Interests Disputes, if any, subject to jurisdiction 39 Reconnecting Kashmir : of courts and competitive tribunals in Need For Reopening Traditional Routes Jammu only. 41 After 2500 Cr Loss, Eyes On Jhelum Valley Road Price : Rs 15 For more News, Views & Analysis Log on to www.epilogue.in Epilogue Ø 1 × September 2008 Epilogue b e c a u s e t h e r e i s m o r e t o k n o w Jammu & Kashmir Center For Contemporary Studies The J&K CCS, a non-profit institute, is engaged in research on issues of contemporary importance involving Jammu and kashmir ANNOUNCEMENT For an upcoming project on people of Jammu and Kashmir, the J&K CCS invites proposals from researchers, scholars, teachers, journalists and other dispassionate observers of life to write brief biographical account of the personalities listed below. -

Accidental Prime Minister

THE ACCIDENTAL PRIME MINISTER THE ACCIDENTAL PRIME MINISTER THE MAKING AND UNMAKING OF MANMOHAN SINGH SANJAYA BARU VIKING Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Books India Pvt. Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, M4P 2Y3, Canada (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) Penguin Group (Australia), 707 Collins Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3008, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) Penguin Group (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, Block D, Rosebank Offi ce Park, 181 Jan Smuts Avenue, Parktown North, Johannesburg 2193, South Africa Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offi ces: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England First published in Viking by Penguin Books India 2014 Copyright © Sanjaya Baru 2014 All rights reserved 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 The views and opinions expressed in this book are the author’s own and the facts are as reported by him which have been verifi ed to the extent possible, and the publishers are not in any way liable for the same. ISBN 9780670086740 Typeset in Bembo by R. Ajith Kumar, New Delhi Printed at Thomson Press India Ltd, New Delhi This book is sold subject to the condition that -

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA U55101DL1998PTC094457 RVS HOTELS AND RESORTS 02700032 BANSAL SHYAM SUNDER U70102AP2005PTC047718 SHREEMUKH PROPERTIES PRIVATE 02700065 CHHIBA SAVITA U01100MH2004PTC150274 DEJA VU FARMS PRIVATE LIMITED 02700070 PARATE VIJAYKUMAR U45200MH1993PTC072352 PARATE DEVELOPERS P LTD 02700076 BHARATI GHOSH U85110WB2007PTC118976 ACCURATE MEDICARE & 02700087 JAIN MANISH RAJMAL U45202MH1950PTC008342 LEO ESTATES PRIVATE LIMITED 02700109 NATESAN RAMACHANDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700110 JEGADEESAN MAHENDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700126 GUPTA JAGDISH PRASAD U74210MP2003PTC015880 GOPAL SEVA PRIVATE LIMITED 02700155 KRISHNAKUMARAN NAIR U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700157 DHIREN OZA VASANTLAL U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700183 GUPTA KEDAR NATH U72200AP2004PTC044434 TRAVASH SOFTWARE SOLUTIONS 02700187 KUMARASWAMY KUNIGAL U93090KA2006PLC039899 EMERALD AIRLINES LIMITED 02700216 JAIN MANOJ U15400MP2007PTC020151 CHAMBAL VALLEY AGRO 02700222 BHAIYA SHARAD U45402TN1996PTC036292 NORTHERN TANCHEM PRIVATE 02700226 HENDIN URI ZIPORI U55101HP2008PTC030910 INNER WELLSPRING HOSPITALITY 02700266 KUMARI POLURU VIJAYA U60221PY2001PLC001594 REGENCY TRANSPORT CARRIERS 02700285 DEVADASON NALLATHAMPI U72200TN2006PTC059044 ZENTERE SOLUTIONS PRIVATE 02700322 GOPAL KAKA RAM U01400UP2007PTC033194 KESHRI AGRI GENETICS PRIVATE 02700342 ASHISH OBERAI U74120DL2008PTC184837 ASTHA LAND SCAPE PRIVATE 02700354 MADHUSUDHANA REDDY U70200KA2005PTC036400 -

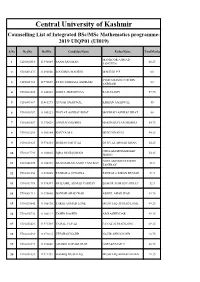

Central University of Kashmir Counselling List of Integrated Bsc/Msc Mathematics Programme- 2019 UIQP01 (UI019)

Central University of Kashmir Counselling List of Integrated BSc/MSc Mathematics programme- 2019 UIQP01 (UI019) S.No RegNo RollNo CandidateName FatherName TotalMarks MANZOOR AHMAD 1 UI10000816 11340004 SANA SANGEEN 60.25 SANGEEN 2 UI10001473 11090006 MANJIMA MAHESH MAHESH P P 60 SYED SHAMSU UD DIN 3 UI10021701 11970629 SYED TABEEZA ANDRABI 60 ANDRABI 4 UI10063020 11240522 GOGULAKRISHNAA RAMASAMY 57.75 5 UI10063867 11461291 AYUSH AGARWAL KISHAN AGARWAL 55 6 UI10035757 11340221 INAYAT ASHRAF BHAT MOHMAD ASHRAF BHAT 55 7 UI10008507 11170028 ANURAG MISHRA HARINARAYAN MISHRA 54.75 8 UI10023258 11600184 KAVYA M S MUKUNDAN M 54.25 9 UI10011025 11970301 SIMRAN IMTIYAZ IMTIYAZ AHMAD KHAN 54.25 GHULAM MOHAMMAD 10 UI10017795 11100065 IQRA MOHAMMAD 54.25 SEROO GHULAM MOHI UD DIN 11 UI10041695 11100338 MUHAMMAD AASIF TANTRAY 53.5 TANTRAY 12 UI10001256 11090005 TANKALA SUNAINA TANKALA KIRAN KUMAR 53.5 13 UI10013798 11970391 MUZAMIL AHMAD PARRAY BASHIR AHMAD PARRAY 52.5 14 UI10001711 11970040 DANISH AHAD WAR ABDUL AHAD WAR 49.75 15 UI10029845 11100136 TARIQ AHMAD LONE MUSHTAQ AHMAD LONE 49.25 16 UI10025720 11100112 ZAHID RASHID AB RASHID DAR 49.25 17 UI10055421 11971369 FAISAL FAYAZ FAYAZ AHMAD LONE 49.25 18 UI10040534 11971015 ZEESHAN NAZIR NAZIR AHMAD MIR 48.75 19 UI10052371 11590086 ARABHI GOPAKUMAR GOPAKUMAR C 48.75 20 UI10054333 11971357 AASHIQ MUSHTAQ MUSHTAQ AHMAD KHAN 48.75 21 UI10009911 11970285 SABIYA ALTAF MOHAMMAD ALTAF BHAT 48.75 22 UI10010691 11600733 SIDDHARTH VIJAYAKUMAR VIJAYAKUMAR P 47.75 23 UI10033086 11470249 HASEEB UR REHMAN NAYEEM -

Primo.Qxd (Page 1)

WEDNESDAY, APRIL 9, 2014 (PAGE 4) DAILY EXCELSIOR, JAMMU From page 1 Army officer, 2 cops, div comdr aamong EC writes to CS, CEO BJP’s misinformation campaign Mirwaiz pins hopes on new MPs said Hurriyat Conference issue would unleash immense 5 killed; 7 injured in Kupwara for free, fair polls exists nowhere on ground: Azad was ready to contribute posi- prosperity and economic bene- the nearby houses and the DIG, South Kashmir, Vijay sensitive and hyper sensitive. ensure that the polling parties and While cautioning the people future as well, with its com- tively towards achieving this fits for the entire South Asia adjoining jungle area is under- Kumar, told Excelsior that mili- "Deployment of any force static armed force parties reaching to remain vigilant against the mitment and dedication goal. region, otherwise the conflict is way", the Defence spokesman tants shot at constable Shabir other than the State’s own uni- polling booths well in time. divisive forces, the Union towards welfare of the peo- "Whoever you vote for and not only a threat to millions of said. Ahmad from a close range at formed police force or the CAPFs "The arrangements for securi- Minister described the hilly ple”, Azad said. whoever ends up forming the Kashmiris but also a serious Some of the injured security Lal chowk in Anantnag town. will require prior approval of the ty of contesting candidates, region of Doda-Kishtwar as He said that Congress party next Government or sitting in hazard for the entire one billion men have been identified as SPO "Militants snatched his rifle", Commission,’’ the letter said, according to perception of threat miniature of secular India. -

Socio-Economic Development During Sheikh Abdullah's

International Journal of Management and Applied Science, ISSN: 2394-7926 Volume-4, Issue-7, Jul.-2018 http://iraj.in SOCIO-ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT DURING SHEIKH ABDULLAH’S PERIOD MOHD. IQBAL WANI PhD. Researcher, Research Centre: - Govt. Hamidia Arts & Commerce College Bhopal (M.P) University, Bharkatullah University Bhopal M.P. E-mail: [email protected] I. INTRODUCTION For this purpose a National Industrial Council is to be set up. About transport manifesto said that anything Sheikh Abdullah (5th December 1905-8th September done for the regeneration of the country must plan 1982) was a Kashmiri politician who played a central simultaneous development of the means of role in the politics of Jammu & Kashmir, the communication and transport. Hence it was proposed northernmost Indian state. The self-styled “ Shere- top set up a National Communications Council Kashmir” (Lion of Kashmir), Abdullah was the consisting of engineering experts and economic founding leader of the Jammu and Kashmir National advisers. The distribution system being the “vital Conference and the 2nd Prime Minister of Princely cornerstone of any planned economy”, it was state J&K and 4th Chief Minister of Jammu and proposed to establish the National Marketing Council Kashmir. He agitated against the rule of the Maharaja costing of business experts and economic advisers. Hari Singh and urged self-rule for Kashmir. On the The National Public Health Council was suggested to last day of Oct 1947 Sheikh Mohammad Abdullah be established for safeguarding the health of the who had led the people of Jammu and Kashmir to citizens. This would propose that every, 1,500 people revolt against serfdom for nearly two decades was will have a doctor, every village a medical attendant, charged to deal with the emergency which had starting of a medical college, encouragement of both suddenly arisen as a result of Pakistan invasion of the Ayurvedic and Union systems of medicines. -

Report on 120 Days 5Th August to 5Th December by Association Of

120 Days 5th August to 5th December Table of Contents About APDP 2 Acknowledgements 3 Executive Summary 5 Introduction 6 Abrogation of 370 9 Detentions and Torture 15 Media, Journalism and Communication 23 Access to Healthcare 32 Education and Children 42 Essential Commodities and Barrier to Trade 53 Impact on Religious Freedom 58 Access to Justice 65 Annexure 83 1 Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP) Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons (APDP) is a collective of relatives of victims of enforced and involuntary disappearances in Kashmir. The APDP was formed in 1994 to organize efforts to seek justice and get information on the whereabouts of missing family members. It presently consists of family members of about one thousand victims. APDP actively campaigns for an end to the practice and crime of involuntary and enforced disappearances at local, national and international platforms. Members of the APDP have been engaged in documenting enforced disappearances in Kashmir since 1989 and have collected information on over one thousand such cases, so far. On the 10th of each month families of the disappeared come together under the aegis of APDP to hold a public protest in Srinagar to commemorate the disappearance of their loved ones and to seek answers from the state about the whereabouts of the missing persons. In light of the recent human rights violation APDP has taken the decision to come forward and bring notice to the current situation. 2 Acknowledgement This report is a result of tireless and bold efforts put in by people from various backgrounds. The report was edited by Shahid Malik, and compiled by Sukriti Khurana and Aarash. -

Of Broken Social Contracts and Ethnic Violence: the Case of Kashmir

1 Working Paper no.75 OF BROKEN SOCIAL CONTRACTS AND ETHNIC VIOLENCE: THE CASE OF KASHMIR Neera Chandhoke Developing Countries Research Centre University of Delhi, India December 2005 Copyright © Neera Chandhoke, 2005 Although every effort is made to ensure the accuracy and reliability of material published in this Working Paper, the Crisis States Research Centre and LSE accept no responsibility for the veracity of claims or accuracy of information provided by contributors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher nor be issued to the public or circulated in any form other than that in which it is published. Requests for permission to reproduce this Working Paper, of any part thereof, should be sent to: The Editor, Crisis States Research Centre, DESTIN, LSE, Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE. Crisis States Research Centre Of Broken Social Contracts and Ethnic Violence: The Case of Kashmir Neera Chandhoke Developing Countries Research Centre, University of Delhi How to find a form of association which will defend the person and goods of each member with the collective force of all, and under which each individual, while uniting himself with the others, obeys no one but himself, and remains as free as before. This is the fundamental problem to which the social contract holds the solution Jean Jacques Rousseau1 Introduction Though what is euphemistically termed ‘the Kashmir problem’ has stalked political life in India since the advent of independence in 1947, it was really in 1988 that the issue acquired serious proportions.