Sustaining Historic Places in Changing Times: a Historic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Old Exchange and Provost Dungeon

The Old Exchange and Provost Dungeon Standards Addressed: Social Studies 3-3: The student will demonstrate an understanding of the American Revolution and South Carolina’s role in the development of the new American nation. 3-3.1 Summarize the causes of the American Revolution, including Britain’s passage of the Stamp Act, the Tea Act, and the Intolerable Acts; the rebellion of the colonists; and the writing of the Declaration of Independence. 3-3.3 Summarize the course of the American Revolution in South Carolina, including the role of William Jasper and Fort Moultrie; the occupation of Charles Town by the British; the partisan warfare of Thomas Sumter, Andrew Pickens, and Francis Marion; and the battles of Cowpens, Kings Mountain, and Eutaw Springs. Visual Arts Standard 1: The student will demonstrate competence in the use of ideas, materials, techniques, and processes in the creation of works of visual art. Indicators VA3-1.1 Use his or her own ideas in creating works of visual art. VA3-1.3 Use and combine a variety of materials, techniques, and processes to create works of visual art. Objectives: 1. Students will demonstrate their understanding of four historical, South Carolina figures and how their roles during the Revolution contributed to Charleston history. 2. Students will make a connection between the four historical accounts and the history/role of the Old Exchange and Provost Dungeon. Materials: Teacher lesson: Write-up- “History of the Old Exchange and Provost Dungeon” Pictures- Labeled A, B, C, D, and E Online virtual -

03050201-010 (Lake Moultrie)

03050201-010 (Lake Moultrie) General Description Watershed 03050201-010 is located in Berkeley County and consists primarily of Lake Moultrie and its tributaries. The watershed occupies 87,730 acres of the Lower Coastal Plain region of South Carolina. The predominant soil types consist of an association of the Yauhannah-Yemassee-Rains- Lynchburg series. The erodibility of the soil (K) averages 0.17 and the slope of the terrain averages 1%, with a range of 0-2%. Land use/land cover in the watershed includes: 64.4% water, 21.1% forested land, 5.4% forested wetland, 4.1% urban land, 3.1% scrub/shrub land, 1.4% agricultural land, and 0.5% barren land. Lake Moultrie was created by diverting the Santee River (Lake Marion) through a 7.5 mile Diversion Canal filling a levee-sided basin and impounding it with the Pinopolis Dam. South Carolina Public Service Authority (Santee Cooper) oversees the operation of Lake Moultrie, which is used for power generation, recreation, and water supply. The 4.5 mile Tail Race Canal connects Lake Moultrie with the Cooper River near the Town of Moncks Corner, and the Rediversion Canal connects Lake Moultrie with the lower Santee River. Duck Pond Creek enters the lake on its western shore. The Tail Race Canal accepts the drainage of California Branch and the Old Santee Canal. There are a total of 43.8 stream miles and 57,535.3 acres of lake waters in this watershed, all classified FW. Additional natural resources in the watershed include the Dennis Wildlife Center near the Town of Bonneau, Sandy Beach Water Fowl Area along the northern lakeshore, the Santee National Wildlife Refuge covering the lower half of the lake, and the Old Santee Canal State Park near Monks Corner. -

Francis Marion Plan FEIS Chapters 1 to 4

In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. To request a copy of the complaint form, call (866) 632-9992. Submit your completed form or letter to USDA by: (1) mail: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Office of the Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, D.C. -

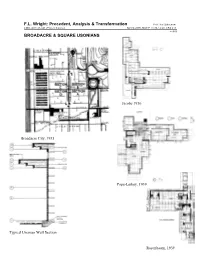

F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation BROADACRE

F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation Prof. Kai Gutschow CMU, Arch 48-441 (Project Course) Spring 2005, M/W/F 11:30-12:20, CFA 211 4/15/05 BROADACRE & SQUARE USONIANS Jacobs 1936 Broadacre City, 1935 Pope-Leihey, 1939 Typical Usonian Wall Section Rosenbaum, 1939 F.L. Wright: Precedent, Analysis & Transformation Prof. Kai Gutschow CMU, Arch 48-441 (Project Course) Spring 2005, M/W/F 11:30-12:20, CFA 211 4/15/05 USONIAN ANALYSIS Sergeant, John. FLW’s Usonian Houses McCarter, Robert. FLW. Ch. 9 Jacobs, Herbert. Building with FLW MacKenzie, Archie. “Rewriting the Natural House,” in Morton, Terry. The Pope-Keihey House McCarter, A Primer on Arch’l Principles P. & S. Hanna. FLW’s Hanna House Burns, John. “Usonian Houses,” in Yesterday’s Houses... De Long, David. Auldbrass. Handlin, David. The Modern Home Reisely, Roland Usonia, New York Wright, Gwendolyn. Building the Dream Rosenbaum, Alvin. Usonia. FLW’s Designs... FLW CHRONOLOGY 1932-1959 1932 FLW Autobiography published, 1st ed. (also 1943, 1977) FLW The Disappearing City published (decentralization advocated) May-Oct. "Modern Architecture" exhibit at MoMA, NY (H.R. Hitchcock & P. Johnson, Int’l Style) Malcolm Wiley Hse., Proj. #1, Minneapolis, MN (revised and built 1934) Oct. Taliesin Fellowship formed, 32 apprentices, additions to Taliesin Bldgs. 1933 Jan. Hitler comes to power in Germany, diaspora to America: Gropius (Harvard, 1937), Mies v.d. Rohe (IIT, 1939), Mendelsohn (Berkeley, 1941), A. Aalto (MIT, 1942) Mar. F.D. Roosevelt inaugurated, New Deal (1933-40) “One hundred days.” 25% unemployment. A.A.A., C.C.C. P.W.A., N.R.A., T.V.A., F.D.I.C. -

Frank Lloyd Wright 978-2-86364-338-9 Cinq Approches ISBN / Approches Cinq

frank lloydwright DANIEL TREIBER DANIEL 978-2-86364-338-9 PARENTHÈSES ISBN cinq approches / approches cinq Wright, Lloyd Frank / Treiber Daniel www.editionsparentheses.com www.editionsparentheses.com WRIGHT, JUSQU’À NOUS Dans ce nouveau livre que je consacre à Frank Lloyd Wright, je me propose d’aborder son œuvre selon cinq approches différentes. 978-2-86364-338-9 L’essai introductif est une présentation de ensemble de ses travaux à travers une lecture des renver- l’ ISBN / sements opérés par chaque nouvelle « période » par rapport à la précédente. Wright a vécu jusqu’à près de 90 ans et, approches tout au long de sa longue vie, l’architecte américain s’est cinq montré capable de se renouveler d’une manière specta- culaire. Plusieurs « styles » se partagent en effet l’œuvre : Wright, une première période presque Art nouveau, une deuxième Lloyd plus singulière et souvent considérée comme un peu énig- Frank matique, d’une ornementation encore plus foisonnante, / puis, enfin, une période délibérément moderne avec la Treiber production d’icônes de l’architecture, la Maison sur la cascade et le musée Guggenheim. La deuxième approche est consacrée au « côté Daniel Ruskin » de Wright. Le grand historien américain Henry-Russell Hitchcock a déclaré dans son Architecture : XIXe et XXe siècles que ce qui faisait la « profonde diffé- rence » entre Frank Lloyd Wright et Auguste Perret, un autre novateur quasiment de la même génération, était que 7 www.editionsparentheses.com www.editionsparentheses.com « l’un avait dans le sang la tradition du néogothique anglais exponentielle de notre environnement, c’est le point par — en bonne part due à ses lectures de Ruskin — tandis lequel les préoccupations de Wright sont étonnamment que l’autre ne l’avait pas ». -

A Retrospective on the Journey

| | EDUCATIONFRANK LLOYD ADVOCACYWRIGHT BUILDING PRESERVATION CONSERVANCY SPRING 2014 / VOLUME 5 / ISSUES 1 & 2 SPECIAL DOUBLE ISSUE A Retrospective on the Journey Guest Editor: Ron Scherubel Past, Present, Future: The Conservancy at 25 2014 CONFERENCE Phoenix, Arizona | Oct. 29 – Nov. 2 Stay for a great rate in the legendary Wright- influenced Arizona Biltmore. Tour seldom-seen houses by Wright and other acclaimed architects. Get a private behind-the-scenes look at Taliesin celebrating years of saving wright West. Attend presentations and panels with world- 25 renowned Wright scholars, including a keynote speech by New York Times architecture critic Michael Kimmelman. And cap it all off with a Gala Dinner, silent auction, Wright Spirit Awards ceremony, and much more! Register beginning in FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT BUILDING CONSERVANCY June at savewright.org or call 312.663.5500 C ON T Editor’s Welcome: OK, What’s Next? 2 EN 2 Executive Editor’s Message: The Power of Community President’s Message: The Challenge Ahead 3 TS 4 Wright and Historic Preservation in the United States, 1950-1975 11 The Origins of the Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy 16 A Day in the Conservancy Office 20 Retrospect and Prospect 22 The ‘Saves’ in SaveWright 28 The Importance of the David and Gladys Wright House PEDRO E. GUERRERO (1917-2012) 30 Saving the David and Gladys Wright House The cover photo of this issue was taken by 38 A New Book Explores Additions to Iconic Buildings Pedro E. Guerrero, Frank Lloyd Wright’s 42 A Future for the Past trusted photographer. Guerrero was just 22 46 Up Close and Personal in 1939 when Wright took an amused look at his portfolio of school assignments and 49 Executive Director’s Letter: For the Next 25 hired him on the spot to document the con- struction at Taliesin West. -

Introduction

Commission Draft Recommended 2/27/17 Introduction Background The basis of the comprehensive planning process is in the South Carolina Local Government Comprehensive Planning Enabling Act of 1994 (SC Code §6‐29‐310 through §6‐29‐1200), which repealed and replaced all existing state statutes authorizing municipal planning and zoning. The 1994 Act establishes the comprehensive plan as the essential first step of the planning process and mandates that the plan must be systematically evaluated and updated. Elements of the plan must be reevaluated at least once every five years, and the entire plan must be updated at least once every ten years. The Town of Moncks Corner is approximately 33 miles from downtown Charleston, South Carolina. Moncks Corner is the county seat of Berkeley County and is also part of the Charleston‐North Charleston Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA). This MSA has experienced rapid growth over recent decades; from 2000 to 2010, the population swelled from 549,033 to 664,607, a 21.1% growth rate. As the Charleston region is growing rapidly, Moncks Corner has begun to experience significant population growth. According to the U.S. Census, the Town’s population grew from 7,885 to 9,873, from 2010 to 2015, which represents a 24.5% increase. Outside the Town, Berkeley County is poised to add to current growth in the Charleston MSA with the arrival of the Volvo manufacturing plant, expected to be completed in 2018. Other manufacturers, such as Audio‐Technica, an audio manufacturing company, have recently opened distribution centers in Moncks Corner. As of June 2016, Berkeley County has recruited $1.1 billion in new economic investments with more than 4,100 jobs announced in only 18 months. -

The Exchange and Provost East Bay Street, At

Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR (July 1969) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE South Carolina COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Charleston INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER (Type all entries — complete applicable sections) The Exchange and Provost AND/OR HISTORIC: The Exchange STREET AND NUMBER: East Bay Street, at the eastern foot of Broad Street CITY OR TOWN: Charleston South Carolina Charleston CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC n District J£X Building n Public Public Acquisition: HV Occupied Yes: Restricted D Site Q Structure (yl Private Q] In Process Unoccupied Unrestricted D Object Both | | Being Considered Preservation work in progress a PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) f~1 Agricultural I | Government D Pork I | Transportation I I Comments I | Commercial | | Industrial I I Private Residence [3 Other (Specify) _______ I | Educational I | Military Q Religious Meeting Place for————— I I Entertainment H Museum I | Scientific PAR_______ _____ PMP E RTY OWNER'S NAME: Rebecca Motte Chapter, Daughters of the American Revolution in and of the State of South Carolina. Mrs. Whitemarsh B. Seabrook) STREET AND NUMBER: Route 2, Box 303, Johns Island, South Carolina 29455 CITY OR TOWN: STATE: Charleston South Carolina COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: Register of Mesne Conveyance STREET AND NUMBER: ________Charieston County Courthouse CITY OR TOWN: STATE Charleston South Carolina TITLE OF SURVEY: Historic American Buildings Survey (1 photo) DATE OF SURVEY: 1938 XX Federal Q State G County Local DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: Library of Congress, Division of Prints and Photographs STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: Washington D.C. -

Free Black Farmers in Antebellum South Carolina David W

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 8-9-2014 Hard Rows to Hoe: Free Black Farmers in Antebellum South Carolina David W. Dangerfield University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Dangerfield, D. W.(2014). Hard Rows to Hoe: Free Black Farmers in Antebellum South Carolina. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/2772 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HARD ROWS TO HOE: FREE BLACK FARMERS IN ANTEBELLUM SOUTH CAROLINA by David W. Dangerfield Bachelor of Arts Erskine College, 2005 Master of Arts College of Charleston, 2009 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2014 Accepted by: Mark M. Smith, Major Professor Lacy K. Ford, Committee Member Daniel C. Littlefield, Committee Member David T. Gleeson, Committee Member Lacy K. Ford, Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies © Copyright by David W. Dangerfield, 2014 All Rights Reserved. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation and my graduate education have been both a labor and a vigil – and neither was undertaken alone. I am grateful to so many who have worked and kept watch beside me and would like to offer a few words of my sincerest appreciation to the teachers, colleagues, friends, and family who have helped me along the way. -

Donald Langmead

FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT: A Bio-Bibliography Donald Langmead PRAEGER FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT Recent Titles in Bio-Bibliographies in Art and Architecture Paul Gauguin: A Bio-Bibliography Russell T. Clement Henri Matisse: A Bio-Bibliography Russell T. Clement Georges Braque: A Bio-Bibliography Russell T. Clement Willem Marinus Dudok, A Dutch Modernist: A Bio-Bibliography Donald Langmead J.J.P Oud and the International Style: A Bio-Bibliography Donald Langmead FRANK LLOYD WRIGHT A Bio-Bibliography Donald Langmead Bio-Bibliographies in Art and Architecture, Number 6 Westport, Connecticut London Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Langmead, Donald. Frank Lloyd Wright : a bio-bibliography / Donald Langmead. p. cm.—(Bio-bibliographies in art and architecture, ISSN 1055-6826 ; no. 6) Includes bibliographical references and indexes. ISBN 0–313–31993–6 (alk. paper) 1. Wright, Frank Lloyd, 1867–1959—Bibliography. I. Title. II. Series. Z8986.3.L36 2003 [NA737.W7] 016.72'092—dc21 2003052890 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright © 2003 by Donald Langmead All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2003052890 ISBN: 0–313–31993–6 ISSN: 1055–6826 First published in 2003 Praeger Publishers, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.praeger.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the -

Reevaluating Early Methods of Survey with a Case Study in St. John's Parish Kristina Poston Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 5-2018 It's Not All Water Under the Bridge: Reevaluating Early Methods of Survey with a Case Study in St. John's Parish Kristina Poston Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Recommended Citation Poston, Kristina, "It's Not All Water Under the Bridge: Reevaluating Early Methods of Survey with a Case Study in St. John's Parish" (2018). All Theses. 2872. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/2872 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IT’S NOT ALL WATER UNDER THE BRIDGE: REEVALUATING EARLY METHODS OF SURVEY WITH A CASE STUDY IN ST. JOHN’S PARISH A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Historic Preservation by Kristina Poston May 2018 Accepted by: Carter Hudgins, Committee Chair Amalia Leifeste Katherine Pemberton Richard Porcher ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank the members of my thesis committee who guided me through this process. Special thanks is given to Richard Porcher who not only shared his archives but his wealth of knowledge. I would also like to extend my gratitude to those home owners who allowed me to roam their property in search of buildings. Finally, this thesis could not have been accomplished without the love and support from all my friends and family. -

Photographs of American Architecture and Architecture in Austria, Belgium, England, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Mexico, Scotland, and Spain Mss 302

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8cc11jp No online items Guide to the Photographs of American architecture and architecture in Austria, Belgium, England, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Mexico, Scotland, and Spain Mss 302 UC Santa Barbara Library, Department of Special Collections University of California, Santa Barbara Santa Barbara, California, 93106-9010 Phone: (805) 893-3062 Email: [email protected]; URL: http://www.library.ucsb.edu/special-collections 2013 Mss 302 1 Title: Photographs of American architecture and architecture in Austria, Belgium, England, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Mexico, Scotland, and Spain Identifier/Call Number: Mss 302 Contributing Institution: UC Santa Barbara Library, Department of Special Collections Language of Material: English Physical Description: 39.0 linear feet(94 document boxes) Date (inclusive): 1936-1983 Abstract: American and European architectural images totaling four thousand one hundred and eighty-three images (4,183) two thirds of which are of American architecture and the rest European, with a small number of images from Mexico. Physical location: For current information on the location of these materials, please consult the library's online catalog. General Physical Description note: (94 document boxes) Creator: Andrews, Wayne Access Use of the collection is unrestricted. Publication Rights Copyright has not been assigned to the Department of Special Collections, UCSB. All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the Head of Special Collections. Permission for publication is given on behalf of the Department of Special Collections as the owner of the physical items and is not intended to include or imply permission of the copyright holder, which also must be obtained.