Heat and Light Thematised in the Modern Architecture of Houston

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Xavier University 160Th Commencement Exercises, 1998 Xavier University, Cincinnati, OH

Xavier University Exhibit Xavier University Commencement Ceremonies University Archives and Special Collections Digital Collection 5-16-1998 Xavier University 160th Commencement Exercises, 1998 Xavier University, Cincinnati, OH Follow this and additional works at: https://www.exhibit.xavier.edu/commencement 1 998 XAVIER UNIVERSITY 160TH COMMENCEMENT MAY 16,1998 8:45AM My VISION FOR XAVIER "My vision for Xavier is simple. What I want most of all is that a Xavier education be ofsuch qualitythat each and every graduate will say: 'I received an absolutely superb education at Xavier. I could not have received a finer education any where in the world.' I want every Xavier graduate to say: 'I know that I am intellectually, morally and spiritually pre pared to take my place in a rapidly changing global society and to have a positive impact on that society - to live a life beyond myself for other people.' " James E. Hoff S.] President Xavier Uniz}ersity My VISION FOR XAVIER "My vision for Xavier is simple. What 1 want most of all is that a Xavier education be ofsuch quality that each and every graduate will say: 'I received an absolutely superb education at Xavier. 1 could not have received a finer education any where in the world.' 1 want every Xavier graduate to say: 'I know that I am intellectually, morally and spiritually pre pared to take my place in a rapidly changing global society and to have a positive impact on that society - to live a life beyond myself for other people.' " James E. Hoff, S.]. President Xtwier University XAVIER UNIVERSITY BOARD OF TRUSTEES Michael]. -

Structural Systems for Tall Apartment Towers 1. Book Chapter/Part

ctbuh.org/papers Title: Structural Systems for Tall Apartment Towers Author: Joseph Colaco, CBM Engineers Subject: Structural Engineering Keyword: Structure Publication Date: 2005 Original Publication: CTBUH 2005 7th World Congress, New York Paper Type: 1. Book chapter/Part chapter 2. Journal paper 3. Conference proceeding 4. Unpublished conference paper 5. Magazine article 6. Unpublished © Council on Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat / Joseph Colaco Joseph P. Colaco, Ph.D., P.E. CBM Engineers, Inc. Joseph Phillip Colaco is among the leading specialists in building structures worldwide. He has made notable contributions to the advancement of the design and construction practice of structural engineering as it applies to tall buildings. He received his Bachelor of Science in Civil Engineering from the University of Bombay, his Master of Science in Civil Engineering from the University of Illinois, and his Doctorate of Philosophy in Civil Engineering from the University of Illinois. He began his career with the consulting firm of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill in Chicago, where he worked on the 100-story steel John Hancock Building in Chicago and the 50-story reinforced-concrete One Shell Plaza in Houston. Since 1975, Dr. Colaco has been the president of CBM Engineers, Inc., in Houston. He has done the conceptual design of 50 major building projects. Dr. Colaco is a member of the National Academy of Engineers, American Society of Civil Engineers, and the American Concrete Institute. He is a fellow of the Institute of Structural Engineers, U.K., and the American Society of Civil Engineers. ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Structural Systems for Tall Apartment Towers The early development of structural systems for tall buildings concentrated on tall office towers. -

2018 Policy Summit 2018 Policy Advisory Committee Accomplishments

2018 POLICY SUMMIT 2018 POLICY ADVISORY COMMITTEE ACCOMPLISHMENTS BUSINESS ISSUES The Business Issues Advisory Committee analyzed two issues that measure's unsustainable cost. The committee also passed a resolution would threaten the business climate of Houston: firefighter pay parity opposing local ordinances that infringe on private employer-employee and paid sick leave. The committee passed a resolution opposing agreements related to paid sick leave. During the 2019 Texas the fire union’s pay initiative due to the damage the measure would Legislative Session, the Partnership will work with a statewide coalition cause to the City’s fiscal health. The resolution resulted in the to support this resolution. formation of a PAC and an awareness campaign highlighting the EDUCATION The Education Advisory Committee determined that public school Members learned from experts in the field of public school finance finance should be its top priority. Due to the design of the formula and leaders who drive the political landscape surrounding the issue. funding system, the state's share of public education funding has Speakers included Jimmie Don Aycock, David Thompson, Sheryl consistently decreased over the past ten years to 38 percent of the Pace and Todd Williams. Leading up to the Texas Legislative Session, total cost. In 2018, the committee launched a process to identify the goal of the committee is to identify key principles to school solutions for a system that provides adequate and effective funding finance reform and establish the Houston business community as a for our children and for the creation of a skilled workforce. leading voice in enacting solutions in school finance. -

Ely Washington 0250O 19621.Pdf (9.561Mb)

Internalizing the Sun An Exploration in Light-Driven Architecture Sri Gaura Ely A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture University of Washington 2019 Committee: Christopher Meek Ann Marie Borys Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Architecture © Copyright 2019 Sri Gaura Ely University of Washington Abstract Internalizing the Sun An Exploration in Light-Driven Architecture Sri Gaura Ely Chairs of the Supervisory Committee: Christopher Meek Ann Marie Borys Can architecture utilize light to evoke a feeling of the sublime? This thesis is an exploration of daylight- driven architecture, architecture that is designed to utilize direct sunlight and ambient skylight for specifically prescribed effects. The foundation of this project draws on the thinking of architectural masters, the perspective of lighting experts, and the lessons of precedent studies to direct a process of designing architecture that allows occupants to approach a sense of divinity. I believe that architecture is at its best when shelter, space, symbolism, and function are balanced with a desire to delight. Architecture’s ability to elicit emotion from individuals, to incite wonder and awe, largely through occupation, is special. In order to exceed programmatic requirements and provoke an emotional response, the endeavor is to create architecture that is akin to art. The proposal explored is an architecture which utilizes natural light to evoke the sublime through its cosmic connection with the sun, sky, and horizon. Internalizing the Sun An Exploration in Light-Driven Architecture Sri Gaura Ely Committee: Christopher Meek Ann Marie Borys Dedication This thesis is dedicated to my parents, Kosarupa and Bada Haridas, to my brother Charles, to my dearest friends, you know who you are, and to my community of well-wishers. -

Fall 2019 Phd Lecture Series

Fall 2019 PhD Program in Architecture Illinois Institute of Technology PHD LECTURE SERIES Architecture, History & Technology August Welcome Back Meeting 22 Wel come August Joseph Colaco 29 Scholar, Department of Engineering and Computing , Florida International University, Miami Professor, College of Architecture, University of Houston Creativity in the Selection of Structural Systems for Tall Buildings September Ian Trivers 5 Visiting Assistant Professor of Urban Design, Washington University Mobilizing the High Line September Robert McCarter 12 Author, Architect, and Ruth and Norman Moore Professor of Architecture, Washington University in St. Louis The Space Within: Interior Experience as the Origin of COLACO Architecture September Kristin Jones 19 Adjunct Professor of Architecture, IIT TRIVERS From Critical to Transformative Pedagogy in Architectural McCARTER Education September Leonard R. Bachman JONES 26 Architect, Professor of Architecture, University of Houston, 1978-2019 (Retired) Constructing the Architect; the Missing Meta-Discourse BACHMAN October Carolyn Armenta Davis DAVIS 3 Hon. AIA, Independent Architecture Historian, Curator and Lecturer Forward: Globalization + Africa Diaspora Architects SULLIVAN October William Sullivan RAO 10 Professor and Director, Rokwire: Illinois’ Smart, Healthy Community Initiative Office of the Provost, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Urban Design, Nature, Health MANSURY October Ajith Rao GEVA 17 Senior Researcher, USG Predictive Modeling & Simulation in R&D Decision Making GOFFI October -

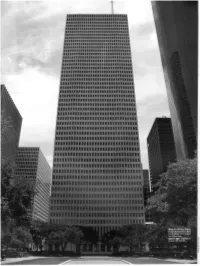

35 Years of One Shell Plaza

iiiiiilliiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiini IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII =IIB ••••••••••••••••••iiiiiiiiiini i ........ aasS§| iiiiiiimiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiui IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII IIIIIIIIIIIBIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII /flffllfllfff IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIII fllllllflllll firfiffiifin IIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIRII /ifffiffifiii llllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll fiifiiifiini "?ffiiiifiii 1111111111111111111111111111111 »lfffifilllii nmmun «lllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll i«»ni llllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll s llllllllllmmmllllllllmll IHIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIIl IIIIIIIIHIIIIIIIIIHimillllll ^IIIIEPIIIll till Ellililllllll llllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll Ss lllllllllllllllllllllllltlllllll railllllllllBl^llllJIIll I '0^4 CITE 67 : SUMMER 2006 25 35 Years of One Shell Plaza Once the world's tallest concrete building, One Shell Plaza still has lessons to teach INTERVIEW W I T H J O S E P H C O L A C O BY W I L L I A M F. S T E R N A N D C H R I S T O F S P I E L E R When it wus finished m Il>7l, One Shell tin this project, research that has served beams welded together at very, very close the post modern movement came about. Plaza was the world's tallest concrete the industry well over many, many years. S[\K nig. I he World 11.ufe i enter had Before that we had basically a Miesi.m- building. The 7IS-foot, 50-story build- And then when I moved ro Houston in columns that were three-feet-four-inches type design, which some call International ing, which fills the block bounded by I4f>^, the building was just about fin- on center on the outside and a very deep Style, buildings were fairly regular. They Louisiana. Smith. Walker, and McKinney. ished. For the last 3.5 years, I have been spandrel beam. F.ssenrially, you could were rectangular, ihey prcttv much went was also Gerald D. -

Seminar Speaker-Colaco.Pdf

The Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering at the University of Houston presents... The CIVE 6111 Graduate Seminar Series Dr. Joseph Colaco President CBM Engineers, Inc. Professor Gerald D. Hines College of Architecture and Design University of Houston Friday, October 26, 2018 2:45PM-3:45PM Classroom Business Building (CBB) Room 108 Seminar Topic Dr. Colaco will discuss the three projects listed below. • 100 John Hancock Center • 75 Story J.P. Morgan Chase • 50 story One Shell Plaza Bio Joseph Philip Colaco, President of CBM Engineers, Inc. and Professor with the Gerald D. Hines College of Architecture and Design at the University of Houston, is among the leading specialists in building structures worldwide. He has made notable contributions to the advancement of the design and construction practice of structural engineering as it applies to tall buildings. After receiving his PhD in civil structural engineering from the University of Illinois in 1965, he began his career with the consulting firm of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill in Chicago. There he worked on the 100- story steel John Hancock Building in Chicago and the 50-story reinforced concrete One Shell Plaza in Houston, Texas. Since 1975, Colaco has been the president of CBM Engineers, Inc. He has done the conceptual design of 50 major building projects, including the 75-story J. P. Morgan/Chase Tower and the 64-story Williams Tower in Houston among many other projects. Colaco is a member of the National Academy of Engineers, American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE), and the American Concrete Institute and a Fellow of the Institute of Structural Engineers, U.K. -

J O U R N a L of the One Hundred Seventieth

J O U R N A L OF THE One Hundred Seventieth ANNUAL COUNCIL Volume II AND DIRECTORY OF THE DIOCESE OF TEXAS The Woodlands Marriott Waterway Hotel and Convention Center February 21 - 23 2019 THE PROTESTANT EPISCOPAL CHURCH IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA The Most Reverend Michael B. Curry, Presiding Bishop & Primate Ms. Gay Clark Jennings, President of the House of Deputies OFFICERS OF THE SEVENTH PROVINCE President: Ms. Sherry Denton, Diocese of Western Kansas Vice-President: Ms. Sherry Denton, Diocese of Western Kansas Secretary: Ms. Kate Huston, Diocese of Oklahoma Treasurer: The Reverend Nancy Igo, Northwest Texas DIOCESE OF TEXAS DIOCESAN OFFICE: 1225 Texas Avenue; Houston, Texas 77002-3504 Texas was administered as a Foreign Mission from 1838 to 1845, being visited by Bishop Polk of Louisiana and Bishop Freeman of Arkansas. When Texas became a state of the union in 1845, it continued under the care of Bishop Freeman. The Diocese of Texas was organized in 1849 and continued under Bishop Freeman’s care until Bishop Gregg was consecrated. The original diocese, comprising the whole state, was divided in 1874. Since that time, the Diocese of Texas has been made up of the 57 counties of southeast and east Texas, viz: that portion of the State of Texas lying south of the northern line of the counties of Lampasas, Coryell, McLennan, Limestone, Freestone, Anderson, Smith, Gregg, and Marion, and east of the western line of the counties of Matagorda, Colorado, Fayette, Bastrop, Travis, Burnet, and Lampasas. Population: 1970-4,103,046; 1980-5,582,119; 1990-6,497,200; 2000-8,182,990; 2010-10,098,913 Sq. -

Cover and Table of Contents

4 Non-Profit Org. 0 Rice Design Alliance * 5 W d S f M P V U U f IN William Marsh Rice University £Z5". Postage Pa/t/ 0 P.O. Box 1892 faTii BURNING l^EE Houston, Texas Houston, Texas 77251 T7T36 Permit No. 7?49 A Publication of the Rice Design Alliance Winter 1984 S2.00 The Architecture and Design Review of Houston r S\ Fourth Ward Overview Allen Parkway Village py**-,, > i tfc •% '*> Phillip Lopate on Public Space in Houston 2 Cite Winter 1984 InCite 3 Citelines 6 Citeations 8 Citesurvey m& 10 A Fourth Ward Overview 13 Wielding the HACHet at Allen Parkway Village Cite 14 An Update From Freedman's Town 17 The Greening of Allen Parkway Village Cover: House on Robin Street. A shotgun 15 Pursuing the Unicorn: Public Space cottage typical of those built in the Fourth in Houston 0** Ward (Photo by Paul Hester) 22 HindCite Editorial Committee John Kaliski Elizabeth S. Glassman Peter C. Papademetriou Chairman Mark A. Hewitt Macey Reasoner Richard Keating Andrew John Rudnick Raymond D. Brochstein O.Jack Mitchell William F. Stem Dana Cuff W.James Murdaugh Drexel Turner Herman Dyal, Jr. Janet M, O'Brien Bruce C Webb *jmK• Guest Editor: John Kaliski Cite welcomes unsolicited manuscripts. Managing Editor Linda Leigh Sylvan Authots take full responsibility for Design Director: Herman Dyal, Jr. securing required consents and releases •:'::••':•' + Graphic Designer Lorraine Wild and for the authenticity of their articles. Publisher: Lynette M. Gannon All manuscripts will be considered by the Editorial Board. Suggestions for topics The opinions expressed in Cite do not are also welcome. -

The Rothko Chapel Rita Reis Colaço Artwork and Space

THE ROTHKO CHAPEL RITA COLAÇO REIS RITA ARTWORK AND SPACE AND ARTWORK / 2017 / the rothko chapel ARTWORK AND SPACE by Rita Reis Colaço Research followed by Sébastien Quequet in order to obtain the diplome in Master in Space & Communication at Haute École d’Art et de Design de Genève First of all, I would like to thank Sébastien Quequet for all knowledge and help he shared with me during the last months. I would also like to thank Alexandra Midal and Vivien Philizot, as well as Helena, Lisa, Maria, Lourenço and Vasco for all the support. I. Introduction | 13 II. The Chapel Commission The Chapel of all tensions | 21 To build or not to build? | 23 Tension, changes and relations generated by the commission through the project | 24 III. Artwork and Space 1. Mark Rothko and the Abstract Expressionism | 41 2. Anatomy of the interaction between the space and the artwork | 45 3. Narration | 101 4. Religion | 109 IV. Conclusion | 119 Endnotes Annexes Bibliography I. Introduction When I concluded my studies on Product Design, I realized that I was much more aware of the space and the environment created through the relation of elements present than just the objects themselves. This interest led me to become very attentive to museum spaces, more specifically to the relation between the space and the artwork and how the space around an artwork influences its observation. I have come to realize that an artwork doesn’t exist without a space around it; an artwork needs a space to live on and to be observed on. -

Westchase NL 1St Qtr 2018 2-18.Indd

WESTCHASETODAY YEAR 20 | ISSUE 1 | SPRING 2018 Higher Ed Options Abound at Nearby Schools College degrees, certifi cates off ered at several institutions in Westchase District School’s in Session (Clockwise from top left): Classes at the Interactive School of Technology are tailored for the busy schedules of adult students; Houston Community College’s Robin Dahms stands in front of a green screen soundstage; Michael Murray can always recommend a Good Book at Fuller Theological Seminary; Danny Rinehart, criminal justice program chair at American InterContinental University shows students how to dust for fi ngerprints; and Eric Happe, Tom Swanson, Doyle Happe and James Scheff er are part of the administration at the Center for Advanced Legal Studies. hether you’re graduating from high school, looking my work, which allowed me to make it in time to attend for many area students. The media arts and technology to take your career to the next level, returning to evening classes. Plus, I felt I had the opportunity to get center of excellence off ers certifi cates and degrees in au- W the workforce or simply wanting to explore new to know my course instructors personally.” dio recording/video production, digital communication, directions, Westchase District off ers several degree- Convenience and class size are just two of the fi lmmaking and music business. HCC has partnered granting higher education options that are worth attractions for area working students seeking to further with the University of Texas at Tyler so that students considering. their education. Here’s a roundup of what’s out there:: may earn a UT Tyler Bachelor’s degree in either civil, “I had looked at other schools downtown, but I electrical or mechanical engineering at a cost of less didn’t want to commute more than an hour each way Arts, engineering and entrepreneurship than $20,000. -

IE Ye ELAND • > W | I • HOUSTON !•'

10 Cite Fall 1984 ike cdif tkai Le4, bejj&ie u, &i j&Ue, v^gzs*- ewe cty ike p44A£4 t ezampled we kaue a a H H"A :-OK city. , ; -•- ^'. Houston's lack o) C: Hou7(ini|caV^uwfli)«iio(iPii(fiotW? 1*1 ' I rlirrl • 'mumttA IM>HH» WI#J •i-inir ' f'l'iin « «r* Umm . * 4 d < • • „ . f . 1 I . P l i t . h - " ' - in-vikiml In *lHf« n i i ' t ><i II.• (minli . umlnrti II x u i kdtn i* t-i Ln | •tot i a J w M l < i < i | i > T T J I * | M i -, •• , .t . I IE yE ELAND • > W | i • HOUSTON !•' N T C t \:,. Clockwise from upper left corner: Ford and Colley and Tamminaga, architects, Dominique de Menil and Philip JoblUOH, 1 949 altered; a modern office and industrial building (Houston Postal. Atrial view oj Gulf Freeway built in the Buffalo Speedway corridor (Houston looking tint from St. Emanuel Street, 1950 Metropolitan Refearch Center, Houston Public (Houston CAamberofCommerce). Welder Hall, Library). Houston grandes dames gathered University of St. Thomas, 19">l), Philip Johnson in a modern living room in the Pine Hill section Associates, architects, Bolton and Rarnstone, of River Oaks. Wilion, Morris, Crain and Mi wt iate architects. View of Commons, altered Anderson, architects (Photo by Beadle, courtesy (PbotO by Alexandre Georges). Meyerland House and GardenJ. The Museum o) Modern Company advertisement, 1958 (Houston Art's "Painting Toward Architecture" exhibi- Chamber of Commerce). Project: Montclair tion on display at the Contemporary A rt<A SJOt lo- Shopping Center, I950.