Spectres of Bruce Lee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

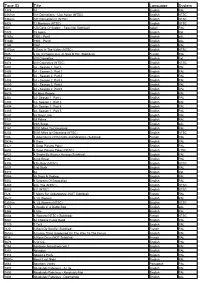

Tape ID Title Language Type System

Tape ID Title Language Type System 1361 10 English 4 PAL 1089D 10 Things I Hate About You (DVD) English 10 DVD 7326D 100 Women (DVD) English 9 DVD KD019 101 Dalmatians (Walt Disney) English 3 PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English 6 NTSC KD040 101 Dalmations (Live) English 3 PAL KD041 102 Dalmatians English 3 PAL 0665 12 Angry Men English 4 PAL 0044D 12 Angry Men (DVD) English 10 DVD 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English 3 NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian 4 PAL 6016 13 Conversations About One Thing (NTSC) English 1 NTSC 0189DN 13 Going On 30 (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 7080D 13 Going On 30 (DVD) English 9 DVD 0179DN 13 Moons (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 3050D 13th Warrior (DVD) English 10 DVD 6291 13th Warrior (NTSC) English 3 nTSC 5172D 1492 - Conquest Of Paradise (DVD) English 10 DVD 3165D 15 Minutes (DVD) English 10 DVD 6568 15 Minutes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 7122D 16 Years Of Alcohol (DVD) English 9 DVD 1078 18 Again English 4 Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English 4 pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English 4 pAL 1244 1941 English 4 PAL 0072DN 1Love (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0141DN 2 Days (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 3256D 2 Fast 2 Furious (DVD) English 10 DVD 5276D 2 Gs And A Key (DVD) English 4 DVD f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French 4 PAL X059D 20 30 40 (DVD) English 9 DVD 1304 200 Cigarettes English 4 Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 3172D 2001 - A Space Odyssey (DVD) English 10 DVD 3032D 2010 - The Year -

Recommended Reading

RECOMMENDED READING The following books are highly recommended as supplements to this manual. They have been selected on the basis of content, and the ability to convey some of the color and drama of the Chinese martial arts heritage. THE ART OF WAR by Sun Tzu, translated by Thomas Cleary. A classical manual of Chinese military strategy, expounding principles that are often as applicable to individual martial artists as they are to armies. You may also enjoy Thomas Cleary's "Mastering The Art Of War," a companion volume featuring the works of Zhuge Liang, a brilliant strategist of the Three Kingdoms Period (see above). CHINA. 9th Edition. Lonely Planet Publications. Comprehensive guide. ISBN 1740596870 CHINA, A CULTURAL HISTORY by Arthur Cotterell. A highly readable history of China, in a single volume. THE CHINA STUDY by T. Colin Campbell,PhD. The most comprehensive study of nutrition ever conducted. ISBN 1-932100-38-5 CHINESE BOXING: MASTERS AND METHODS by Robert W. Smith. A collection of colorful anecdotes about Chinese martial artists in Taiwan. Kodansha International Ltd., Publisher. ISBN 0-87011-212-0 CHINESE MARTIAL ARTS TRAINING MANUALS (A Historical Survey) by Brian Kennedy and Elizabeth Guo CHRONICLES OF TAO, THE SECRET LIFE OF A TAOIST MASTER by Deng Ming-Dao. Harper San Francisco, Publisher ISBN 0-06-250219-0 (Note: This is an abridged version of a three- volume set: THE WANDERING TAOIST (Book I), SEVEN BAMBOO TABLETS OF THE CLOUDY SATCHEL (Book II), and GATEWAY TO A VAST WORLD (Book III)) CLASSICAL PA KUA CHANG FIGHTING SYSTEMS AND WEAPONS by Jerry Alan Johnson and Joseph Crandall. -

Do You Know Bruce Was Known by Many Names?

Newspapers In Education and the Wing Luke Museum of the Asian Pacific American Experience present ARTICLE 2 DO YOU KNOW BRUCE WAS KNOWN BY MANY NAMES? “The key to immortality is living a life worth remembering.”—Bruce Lee To have one English name and one name in your family’s mother tongue is common Bruce began teaching and started for second and third generation Asian Americans. Bruce Lee had two names as well as his first school here in Seattle, on a number of nicknames he earned throughout his life. His Chinese name was given to Weller Street, and then moved it to him by his parents at birth, while it is said that a nurse at the hospital in San Francisco its more prominent location in the where he was born gave him his English name. While the world knows him primarily University District. From Seattle as Bruce Lee, he was born Lee Jun Fan on November 27, 1940. he went on to open schools in Oakland and Los Angeles, earning Bruce Lee’s mother gave birth to him in the Year of the Dragon during the Hour of the him the respectful title of “Sifu” by Dragon. His Chinese given name reflected her hope that Bruce would return to and be his many students which included Young Bruce Lee successful in the United States one day. The name “Lee Jun Fan” not only embodied the likes of Steve McQueen, James TM & (C) Bruce Lee Enterprises, LLC. All Rights Reserved. his parents’ hopes and dreams for their son, but also for a prosperous China in the Coburn, Kareem Abdul Jabbar, www.brucelee.com modern world. -

The Martial Masterâ•Žs Mistresses: Forbidden Desires and Futile Nationalism in Jet Liâ•Žs Kung-Fu Films

UCLA Thinking Gender Papers Title The Martial Master’s Mistresses: Forbidden Desires and Futile Nationalism in Jet Li’s Kung-Fu Films Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6jf832fv Author Meng, Victoria Publication Date 2007-02-01 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California 1 Title: The Martial Master’s Mistresses: Forbidden Desires and Futile Nationalism in Jet Li’s Kung-Fu Films Author: Victoria Meng, Candidate of Philosophy, Cinema and Media Studies, UCLA Abstract: During his 24 years as a kung-fu film icon, Jet Li has repeatedly portrayed the conventional Chinese martial master: the righteous but reluctant leader who ultimately retreats from the world after redirecting his own desires to support supposedly greater moral claims of master and nation. Too preoccupied by his fights and flights, Li’s characters seem unable to give much thought to the women who love him. This consistent failure for Li to “get the girl”—especially given a series of hyper-feminine heroines who should, by rights, be irresistible—suggests that these popular films enact some trauma or taboo for their local audiences. Indeed, I argue that these heroines, each of whom bears a mixed cultural heritage, personify the impossibility of imagining a unified modern Chinese identity, because the films cannot imagine these heroines as fit candidates to raise “culturally pure” children. Li’s steadfast reincarnation as the martial master, then, represents the contemporary Chinese need to elegize a common cultural past as a compensation for the loss of a common cultural future. This essay thus pays homage to and extends feminist film scholar Gina Marchetti’s groundbreaking Romance and the “Yellow Peril,” in which she describes how Hollywood has used the trope of romance to perform and displace its racial fears and fantasies. -

Tape ID Title Language System

Tape ID Title Language System 1375 10 English PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English NTSC 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian PAL 1078 18 Again English Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English pAL 1244 1941 English PAL 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English NTSC f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French PAL 1304 200 Cigarettes English Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English NTSC 2401 24 - Season 1, Vol 1 English PAL 2406 24 - Season 2, Part 1 English PAL 2407 24 - Season 2, Part 2 English PAL 2408 24 - Season 2, Part 3 English PAL 2409 24 - Season 2, Part 4 English PAL 2410 24 - Season 2, Part 5 English PAL 5675 24 Hour People English PAL 2402 24- Season 1, Part 2 English PAL 2403 24- Season 1, Part 3 English PAL 2404 24- Season 1, Part 4 English PAL 2405 24- Season 1, Part 5 English PAL 3287 28 Days Later English PAL 5731 29 Palms English PAL 5501 29th Street English pAL 3141 3000 Miles To Graceland English PAL 6234 3000 Miles to Graceland (NTSC) English NTSC f103 4 Adventures Of Reinette and Mirabelle (Subtitled) French PAL 0514s 4 Days English PAL 3421 4 Dogs Playing Poker English PAL 6607 4 Dogs Playing Poker (NTSC) English nTSC g033 4 Shorts By Werner Herzog (Subtitled) English PAL 0160 42nd Street English PAL 6306 4Th Floor (NTSC) English NTSC 3437 51st State English PAL 5310 54 English Pal 0058 55 Days At Peking English PAL 3052 6 Degrees Of Separation English PAL 6389 60s, The (NTSC) English NTSC 6555 61* (NTSC) English NTSC f126 7 Morts Sur Ordonnance (NOT Subtitled) French PAL 5623 8 1/2 Women English PAL 0253sn 8 1/2 Women (NTSC) English NTSC 1175 8 Heads In A Duffel Bag English pAL 5344 8 Mile English PAL 6088 8 Women (NTSC) (Subtitled) French NTSC 5041 84 Charing Cross Road English PAL 1129 9 To 5 English PAL f220 A Bout De Souffle (Subtitled) French PAL 0652s A Funny Thing Happened On The Way To The Forum English PAL f018 A Nous Deux (NOT Subtitled) French PAL 3676 A.W.O.L. -

Fundamental Iron Skills

FUNDAMENTAL IRON SKILLS TEMPERING BODY AND LIMBS WITH ANCIENT METHODS FUNDAMENTAL IRON SKILLS TEMPERING BODY AND LIMBS WITH ANCIENT METHODS DR. DALE DUGAS www.TambuliMedia.com Spring House, PA USA Disclaimer The author and publisher of this book are NOT RESPONSIBLE in any manner whatsoever for any injury that may result from practicing the techniques and/or following the instructions given within. Since the physical activities described herein may be too strenuous in nature for some readers to engage in safely, it is essential that a physician be con- sulted prior to training. First Published August 25, 2015 Copyright ©2014 Dale Dugas ISBN-10: 1-943-155-119 ISBN-13: 978-1-943155-11-8 Library of Congress Control Number: 2015943528 All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior written permission from the Publisher or Author. Edited by Arnaldo Ty Núñez Cover & Interior by Summer Bonne iv Fundamental Iron Skills FOREWORD Dale Dugas and I met 20 years ago in a Vietnamese restaurant in Boston’s Chinatown. He was living in the area and studying traditional Chinese medicine and acupuncture and I was martial arts editor at Tuttle Publish- ing, recently relocated from their Tokyo office to their Boston office. We met for Pho and café sua da, and discussed kung-fu. We had a common friend between us, Renee Navarro, whom we talked about, too, and I found Dale to be full of energy and passion for the arts. -

FILM DI ARTI MARZIALI - Superlista " Più Di 500 Film Ordinati Dalla a Alla Z "

FILM DI ARTI MARZIALI - SuperLista " Più di 500 Film ordinati dalla A alla Z " ------------------------------------------------------- ACCIDENTAL SPY - SPIA PER CASO (J.Chan 2001) A COLPI DI KARATE' (1972) ALLEY CAT (1984) ALOHA SUMMER (1988) AMERICAN SAMURAI (1992) AMERICAN YAKUZA (1993) AMICI PER LA MORTE (Jet Li 2003) A PUGNI NUDI: LA RIVINCITA (1990) AQUILA NERA - BLACK EAGLE (Van Damme 1988) ARAHAN - POTERE ASSOLUTO (2004) ARMA LETALE 4 (Jet Li 1998) ART OF REVENGE (2007) ARMA PERFETTA (1991) ARMOUR OF GOD (J.Chan aja Armatura D'oro 1986) ARMOUR OF GOD II: OPERATION CONDOR (J.Chan aka Mission Adler 1990) ARRIVO' CHEN E INTORNO A LUI FU MORTE (1975) BANGKOK DANGEROUS (1999) BERSAGLIO UMANO (1993) BILLY CHANG (1975) BILLY JACK (1971) BLACK BELT JONES (Jim Kelly aka La Cintura Nera 1974) BLACK BELT JONES 2: THE TATTOO CONNECTION (Jim Kelli 1977) BLADE (Wesley Snipes 1998) BLADE II (W.Snipes 2002) BLADE III - BLADE TRINITY (W.Snipes 2004) BLADE OF FURY (aka Yat Do King Sing, 1993) BLADE OF FURY 2 (aka Tow Great Cavaliers The, 1973) BLACK MASK (1998) BLACK MASK 2 - CITY OF MASK (2002) BLOOD AND BONE (2009) BLOODMATCH - L'ULTIMA SFIDA (1995) BLOODSPORT - SENZA ESCLUSIONE DI COLPI (V.Damme 1989) BOOK OF SWORDS . LA SPADA E LA VENDETTA (2002) BRUCE AND SHAO-LIN KUNG FU 2 (Bruce Le aka Huo shao shao lin men 1978) BRUCE LEE: CHEN L'IMMORTALE (1972) BRUCE LEE CONTRO I SUPERMEN (1976) BRUCE LEE CONTRO LA SETTA DEL SERPENTE (1977) BRUCE LEE, IL COLPO CHE FRANTUMA (1979) BRUCE LEE IL DOMINATORE (1977) BRUCE LEE, IL LEGGENDARIO (1981) BRUCE LEE, -

20 Movies 20 Years Ebook.Cdr

20 MUST SEE MARTIAL ARTS MOVIES FROM THE LAST 20 YEARS THANK YOU FOR SUBSCRIBING AND DOWNLOADING THIS FREE E-BOOK! EVERY SINGLE PERSON INVOLVED MAKES THE MARTIAL ARTS ACTION MOVIE WEBSITE POSSIBLE... ...AND LOTS OF FUN! BEFORE WE GET STUCK INTO IT. In the last 4 years, I have watched and reviewed close to 500 Martial Arts films. I’ve got to say it’s a bit of an addiction but a fun one, and it’s been shared with a lot of people through Social Media channels like Facebook and Twitter, and I’ve noticed a strong pattern in the movies people love to see these days. On top of that, we’re seeing movies being released that seem to be climbing the ladder in terms of quality. For a while, martial arts movies were heading in a different direction and focusing less on the pure abilities of the actor and relying heavily on wire work. While there’s nothing wrong with that, I can safely say that most people I’ve networked with over the last few years don’t enjoy the weightless “floating” look that most of these movies produced. So most of what I write about these days focuses on the power of the individual martial artist, relying on themselves more than wires. Combined with the totality of the film making process, I’ve done my best to find the absolute most entertaining, action packed and well balanced martial arts films of recent times. So I produced this little Ebook for anyone whose looking to become immersed in the most action packed, adrenaline charged fight films from the last 20 years. -

Approved Movie List 10-9-12

APPROVED NSH MOVIE SCREENING COMMITTEE R-RATED and NON-RATED MOVIE LIST Updated October 9, 2012 (Newly added films are in the shaded rows at the top of the list beginning on page 1.) Film Title ALEXANDER THE GREAT (1968) ANCHORMAN (2004) APACHES (also named APACHEN)(1973) BULLITT (1968) CABARET (1972) CARNAGE (2011) CINCINNATI KID, THE (1965) COPS CRUDE IMPACT (2006) DAVE CHAPPEL SHOW (2003–2006) DICK CAVETT SHOW (1968–1972) DUMB AND DUMBER (1994) EAST OF EDEN (1965) ELIZABETH (1998) ERIN BROCOVICH (2000) FISH CALLED WANDA (1988) GALACTICA 1980 GYPSY (1962) HIGH SCHOOL SPORTS FOCUS (1999-2007) HIP HOP AWARDS 2007 IN THE LOOP (2009) INSIDE DAISY CLOVER (1965) IRAQ FOR SALE: THE WAR PROFITEERS (2006) JEEVES & WOOSTER (British TV Series) JERRY SPRINGER SHOW (not Too Hot for TV) MAN WHO SHOT LIBERTY VALANCE, THE (1962) MATA HARI (1931) MILK (2008) NBA PLAYOFFS (ESPN)(2009) NIAGARA MOTEL (2006) ON THE ROAD WITH CHARLES KURALT PECKER (1998) PRODUCERS, THE (1968) QUIET MAN, THE (1952) REAL GHOST STORIES (Documentary) RICK STEVES TRAVEL SHOW (PBS) SEX AND THE SINGLE GIRL (1964) SITTING BULL (1954) SMALLEST SHOW ON EARTH, THE (1957) SPLENDER IN THE GRASS APPROVED NSH MOVIE SCREENING COMMITTEE R-RATED and NON-RATED MOVIE LIST Updated October 9, 2012 (Newly added films are in the shaded rows at the top of the list beginning on page 1.) Film Title TAMING OF THE SHREW (1967) TIME OF FAVOR (2000) TOLL BOOTH, THE (2004) TOMORROW SHOW w/ Tom Snyder TOP GEAR (BBC TV show) TOP GEAR (TV Series) UNCOVERED: THE WAR ON IRAQ (2004) VAMPIRE SECRETS (History -

Alternative Titles Index

VHD Index - 02 9/29/04 4:43 PM Page 715 Alternative Titles Index While it's true that we couldn't include every Asian cult flick in this slim little vol- ume—heck, there's dozens being dug out of vaults and slapped onto video as you read this—the one you're looking for just might be in here under a title you didn't know about. Most of these films have been released under more than one title, and while we've done our best to use the one that's most likely to be familiar, that doesn't guarantee you aren't trying to find Crippled Avengers and don't know we've got it as The Return of the 5 Deadly Venoms. And so, we've gathered as many alternative titles as we can find, including their original language title(s), and arranged them in alphabetical order in this index to help you out. Remember, English language articles ("a", "an", "the") are ignored in the sort, but foreign articles are NOT ignored. Hey, my Japanese is a little rusty, and some languages just don't have articles. A Fei Zheng Chuan Aau Chin Adventure of Gargan- Ai Shang Wo Ba An Zhan See Days of Being Wild See Running out of tuas See Gimme Gimme See Running out of (1990) Time (1999) See War of the Gargan- (2001) Time (1999) tuas (1966) A Foo Aau Chin 2 Ai Yu Cheng An Zhan 2 See A Fighter’s Blues See Running out of Adventure of Shaolin See A War Named See Running out of (2000) Time 2 (2001) See Five Elements of Desire (2000) Time 2 (2001) Kung Fu (1978) A Gai Waak Ang Kwong Ang Aau Dut Air Battle of the Big See Project A (1983) Kwong Ying Ji Dut See The Longest Nite The Adventures of Cha- Monsters: Gamera vs. -

Kung-Fu Cowboy to Bronx B-Boys: Heroes and the Birth of Hip Hop

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2005 Kung-Fu Cowboys to Bronx B-Boys: Heroes and the Birth of Hip Hop Culture Cutler Edwards Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES KUNG-FU COWBOYS TO BRONX B-BOYS: HEROES AND THE BIRTH OF HIP HOP CULTURE By CUTLER EDWARDS A Thesis submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2005 Copyright © 2005 Cutler Edwards All Rights Reserved The members of the Committee approve the Thesis of Cutler Edwards, defended on October 19, 2005. ______________________ Neil Jumonville Professor Directing Thesis ______________________ Maxine Jones Committee Member ______________________ Matt D. Childs Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii I give this to many people: to my parents, who alternately encouraged, cajoled, and coerced me at the appropriate times in my life—good timing, folks. To my brothers by birth, who are stuck with me, and my brothers and sisters by choice, who stick with me anyway—you are true patriots. Thanks for the late nights, open minds, arguments, ridicule, jests, jibes, and tunes—the turntables might wobble, but they don’t fall down. I could not hope for a better crew. R.I.P. to O.D.B., Jam Master Jay, Scott LaRock, Buffy, Cowboy, Bruce Lee, and the rest of my fallen heroes. -

Historicizing Martial Arts Cinema in Postcolonial Hong Kong: the Ip Man Narratives

IAFOR Journal of Cultural Studies Volume 4 – Issue 2 – Autumn 2019 Historicizing Martial Arts Cinema in Postcolonial Hong Kong: The Ip Man Narratives Jing Yang, Guangdong University of Foreign Studies, China Abstract: The surge of Hong Kong martial arts films in the new millennium transformed the classic genre with a keen consciousness of history. Based loosely on the life experiences of the Cantonese master Ip Man (1893–1972), Ip Man (Yip, 2008) and The Grandmaster (Wong, 2013) utilize the genre to examine the dynamics between Hong Kong and mainland China by integrating the personal with the national. Against the shifting industrial and cultural orientations of Hong Kong cinema and society, the paper argues that the multifarious discourses in both films exemplify the effort to construct a post-colonial identity in negotiation with mainland China. Keywords: Hong Kong martial arts cinema, history, national discourse, postcolonial identity 59 IAFOR Journal of Cultural Studies Volume 4 – Issue 2 – Autumn 2019 Introduction The martial arts trainer of Bruce Lee, Ip Man (1893–1972), has become a recurrent subject matter of Hong Kong cinema more than a decade after China’s resumption of sovereignty over the territory. In a string of Ip Man films released from 2008 to 2015 (Ip Man [Yip, 2010, 2015], The Legend is Born: Ip Man [Yau, 2010], Ip Man: The Final Fight [Yau, 2013] and a 50- episode TV drama Ip Man [Fan, 2013]), Wilson Yip’s Ip Man (2008) and Wong Kar-wai’s The Grandmaster (2013) recount the life experiences of the Cantonese master whose legacy is the global popularity of Wing Chun art.