The 32 Bit X86 C Calling Convention

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strict Protection for Virtual Function Calls in COTS C++ Binaries

vfGuard: Strict Protection for Virtual Function Calls in COTS C++ Binaries Aravind Prakash Xunchao Hu Heng Yin Department of EECS Department of EECS Department of EECS Syracuse University Syracuse University Syracuse University [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract—Control-Flow Integrity (CFI) is an important se- these binary-only solutions are unfortunately coarse-grained curity property that needs to be enforced to prevent control- and permissive. flow hijacking attacks. Recent attacks have demonstrated that existing CFI protections for COTS binaries are too permissive, While coarse-grained CFI solutions have significantly re- and vulnerable to sophisticated code reusing attacks. Accounting duced the attack surface, recent efforts by Goktas¸¨ et al. [9] for control flow restrictions imposed at higher levels of semantics and Carlini [10] have demonstrated that coarse-grained CFI is key to increasing CFI precision. In this paper, we aim to provide solutions are too permissive, and can be bypassed by reusing more stringent protection for virtual function calls in COTS large gadgets whose starting addresses are allowed by these C++ binaries by recovering C++ level semantics. To achieve this solutions. The primary reason for such permissiveness is the goal, we recover C++ semantics, including VTables and virtual lack of higher level program semantics that introduce certain callsites. With the extracted C++ semantics, we construct a sound mandates on the control flow. For example, given a class CFI policy and further improve the policy precision by devising two filters, namely “Nested Call Filter” and “Calling Convention inheritance, target of a virtual function dispatch in C++ must Filter”. -

Tricore Architecture Manual for a Detailed Discussion of Instruction Set Encoding and Semantics

User’s Manual, v2.3, Feb. 2007 TriCore 32-bit Unified Processor Core Embedded Applications Binary Interface (EABI) Microcontrollers Edition 2007-02 Published by Infineon Technologies AG 81726 München, Germany © Infineon Technologies AG 2007. All Rights Reserved. Legal Disclaimer The information given in this document shall in no event be regarded as a guarantee of conditions or characteristics (“Beschaffenheitsgarantie”). With respect to any examples or hints given herein, any typical values stated herein and/or any information regarding the application of the device, Infineon Technologies hereby disclaims any and all warranties and liabilities of any kind, including without limitation warranties of non- infringement of intellectual property rights of any third party. Information For further information on technology, delivery terms and conditions and prices please contact your nearest Infineon Technologies Office (www.infineon.com). Warnings Due to technical requirements components may contain dangerous substances. For information on the types in question please contact your nearest Infineon Technologies Office. Infineon Technologies Components may only be used in life-support devices or systems with the express written approval of Infineon Technologies, if a failure of such components can reasonably be expected to cause the failure of that life-support device or system, or to affect the safety or effectiveness of that device or system. Life support devices or systems are intended to be implanted in the human body, or to support and/or maintain and sustain and/or protect human life. If they fail, it is reasonable to assume that the health of the user or other persons may be endangered. User’s Manual, v2.3, Feb. -

IAR C/C++ Compiler Reference Guide for V850

IAR Embedded Workbench® IAR C/C++ Compiler Reference Guide for the Renesas V850 Microcontroller Family CV850-9 COPYRIGHT NOTICE © 1998–2013 IAR Systems AB. No part of this document may be reproduced without the prior written consent of IAR Systems AB. The software described in this document is furnished under a license and may only be used or copied in accordance with the terms of such a license. DISCLAIMER The information in this document is subject to change without notice and does not represent a commitment on any part of IAR Systems. While the information contained herein is assumed to be accurate, IAR Systems assumes no responsibility for any errors or omissions. In no event shall IAR Systems, its employees, its contractors, or the authors of this document be liable for special, direct, indirect, or consequential damage, losses, costs, charges, claims, demands, claim for lost profits, fees, or expenses of any nature or kind. TRADEMARKS IAR Systems, IAR Embedded Workbench, C-SPY, visualSTATE, The Code to Success, IAR KickStart Kit, I-jet, I-scope, IAR and the logotype of IAR Systems are trademarks or registered trademarks owned by IAR Systems AB. Microsoft and Windows are registered trademarks of Microsoft Corporation. Renesas is a registered trademark of Renesas Electronics Corporation. V850 is a trademark of Renesas Electronics Corporation. Adobe and Acrobat Reader are registered trademarks of Adobe Systems Incorporated. All other product names are trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. EDITION NOTICE Ninth edition: May 2013 Part number: CV850-9 This guide applies to version 4.x of IAR Embedded Workbench® for the Renesas V850 microcontroller family. -

Lecture 21: Calling Conventions Menu Calling Convention Calling Convention X86 C Calling Convention

CS216: Program and Data Representation University of Virginia Computer Science Spring 2006 David Evans Menu Lecture 21: Calling Conventions • x86 C Calling Convention • Java Byte Code Wizards http://www.cs.virginia.edu/cs216 UVa CS216 Spring 2006 - Lecture 21: Calling Conventions 2 Calling Convention Calling Convention • Rules for how the caller and the Caller Callee callee make subroutine calls • Where to put • Where to find • Caller needs to know: params params • What registers can I • What registers – How to pass parameters assume are same must I not bash – What registers might be bashed by • Where to find result • Where to put result called function • State of stack • State of stack – What is state of stack after return – Where to get result UVa CS216 Spring 2006 - Lecture 21: Calling Conventions 3 UVa CS216 Spring 2006 - Lecture 21: Calling Conventions 4 Calling Convention: x86 C Calling Convention Easiest for Caller Caller Callee Caller Callee • Where to put • Where to find • Params on stack in • Find params on stack params params reverse order in reverse order • What registers can I • What registers • Can assume EBX, • Must not bash EBX, assume are same must I not bash EDI and ESI are EDI or ESI – All of them – None of them same • Put result in EAX • Where to find result • Where to put result • Find result in EAX • Stack rules next • State of stack • State of stack • Stack rules next Need to save and Need to save and restore restore EBX, EDI (EAX), ECX, EDX and ESI UVa CS216 Spring 2006 - Lecture 21: Calling Conventions 5 UVa CS216 -

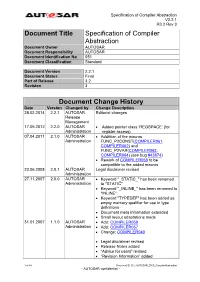

Specification of Compiler Abstraction

Specification of Compiler Abstraction V2.2.1 R3.2 Rev 3 Document Title Specification of Compiler Abstraction Document Owner AUTOSAR Document Responsibility AUTOSAR Document Identification No 051 Document Classification Standard Document Version 2.2.1 Document Status Final Part of Release 3.2 Revision 3 Document Change History Date Version Changed by Change Description 28.02.2014 2.2.1 AUTOSAR Editorial changes Release Management 17.05.2012 2.2.0 AUTOSAR Added pointer class ‘REGSPACE’ (for Administration register access) 07.04.2011 2.1.0 AUTOSAR Addtition of the macros Administration FUNC_P2CONST(COMPILER061, COMPILER062) and FUNC_P2VAR(COMPILER063, COMPILER064) (see bug #43874) Rework of COMPILER058 to be compatible to the added macros 23.06.2008 2.0.1 AUTOSAR Legal disclaimer revised Administration 27.11.2007 2.0.0 AUTOSAR Keyword "_STATIC_" has been renamed Administration to "STATIC" Keyword "_INLINE_" has been renamed to "INLINE" Keyword "TYPEDEF" has been added as empty memory qualifier for use in type definitions Document meta information extended Small layout adaptations made 31.01.2007 1.1.0 AUTOSAR Add: COMPILER058 Administration Add: COMPILER057 Change: COMPILER040 Legal disclaimer revised Release Notes added “Advice for users” revised “Revision Information” added 1 of 44 Document ID 051: AUTOSAR_SWS_CompilerAbstraction - AUTOSAR confidential - Specification of Compiler Abstraction V2.2.1 R3.2 Rev 3 Document Change History Date Version Changed by Change Description 27.04.2006 1.0.0 AUTOSAR Initial Release Administration 2 of 44 Document ID 051: AUTOSAR_SWS_CompilerAbstraction - AUTOSAR confidential - Specification of Compiler Abstraction V2.2.1 R3.2 Rev 3 Disclaimer This specification and the material contained in it, as released by AUTOSAR is for the purpose of information only. -

EECS 373 Design of Microprocessor-Based Systems

Procedures Procedures are very important for writing reusable and maintainable code in assembly and high-level languages. How are they implemented? · Application Binary Interfaces · Calling Conventions · Recursive Calls · Examples Reference: PowerPC Embedded ABI General Concepts · Caller: The calling procedure Callee: The procedure called by the caller ¼ int mult(x, y) prod = mult (a, b) ¼ ¼ return (x * y) · Caller and callee must agree on: · How to pass parameters · How to return the return value(s), if any · How to maintain relevant information across calls · PowerPC architecture does not define ªagreementº. Instead, common policies are defined by convention. PowerPC Features The PowerPC ISA provides the following features to support procedure/function calls: · link register (p. 2-11) · bl: branch and link (p. 4-41) · blr: branch to link register (Table F-4) A Very Simple Calling Convention · Passing arguments · Use GPRs r3 to r10 in order · Use stack in main memory if more than 8 arguments · Passing return value · Leave result in r3 Example int func(int a, int b) { return (a + b); } main { ¼ func(5,6); ¼ } Another Example int func2(int a, int b) { return func(a , b); } main { ¼ func2(5,6); ¼ } The Stack · Information for each function invocation (e.g. link register) is saved on the call stack or simply stack. · Each function invocation has its own stack frame (a.k.a. activation record ). high address func2 stack frame func stack frame stack pointer low address Using the Stack main ¼ Describe the stack and LR contents ¼ · right before -

Calling Convention

ESWEEK Tutorial 4 October 2015, Amsterdam, Netherlands Lucas Davi, Christopher Liebchen, Ahmad-Reza Sadeghi CASED, Technische Universität Darmstadt Intel Collaborative Research Institute for Secure Computing at TU Darmstadt, Germany http://trust.cased.de/ Motivation • Sophisticated, complex • Various of different developers • Native Code Large attack surface for runtime attacks [Úlfar Erlingsson, Low-level Software Security: Attacks and Defenses, TR 2007] Introduction Vulnerabilities Programs continuously suffer from program bugs, e.g., a buffer overflow Memory errors CVE statistics; zero-day In this tutorial Runtime Attack Exploitation of program vulnerabilities to perform malicious program actions Control-flow attack; runtime exploit Three Decades of Runtime Attacks return-into- Return-oriented Morris Worm libc programming Continuing Arms 1988 Solar Designer Shacham Race 1997 CCS 2007 … Borrowed Code Code Chunk Injection Exploitation AlephOne Krahmer 1996 2005 Are these attacks relevant? Relevance and Impact High Impact of Attacks • Web browsers repeatedly exploited in pwn2own contests • Zero-day issues exploited in Stuxnet/Duqu [Microsoft, BH 2012] • iOS jailbreak Industry Efforts on Defenses • Microsoft EMET (Enhanced Mitigation Experience Toolkit) includes a ROP detection engine • Microsoft Control Flow Guard (CFG) in Windows 10 • Google‘s compiler extension VTV (vitual table verification) Hot Topic of Research • A large body of recent literature on attacks and defenses Stagefright [Drake, BlackHat 2015] These issues in Stagefright -

“Option Summary” in Using the GNU Compiler Collection (GCC)

Using the GNU Compiler Collection For gcc version 4.3.6 (GCC) Richard M. Stallman and the GCC Developer Community Published by: GNU Press Website: www.gnupress.org a division of the General: [email protected] Free Software Foundation Orders: [email protected] 51 Franklin Street, Fifth Floor Tel 617-542-5942 Boston, MA 02110-1301 USA Fax 617-542-2652 Last printed October 2003 for GCC 3.3.1. Printed copies are available for $45 each. Copyright c 1988, 1989, 1992, 1993, 1994, 1995, 1996, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, 2007 2008 Free Software Foundation, Inc. Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with the Invariant Sections being “GNU General Public License” and “Funding Free Software”, the Front-Cover texts being (a) (see below), and with the Back-Cover Texts being (b) (see below). A copy of the license is included in the section entitled “GNU Free Documentation License”. (a) The FSF’s Front-Cover Text is: A GNU Manual (b) The FSF’s Back-Cover Text is: You have freedom to copy and modify this GNU Manual, like GNU software. Copies published by the Free Software Foundation raise funds for GNU development. i Short Contents Introduction ............................................. 1 1 Programming Languages Supported by GCC ............... 3 2 Language Standards Supported by GCC .................. 5 3 GCC Command Options ............................... 9 4 C Implementation-defined behavior ..................... 237 5 Extensions to the C Language Family .................. -

Porting GCC for Dunces

Porting GCC for Dunces Hans-Peter Nilsson∗ May 21, 2000 ∗Email: <[email protected]>. Thanks to Richard Stallman <[email protected]> for guidance to letting this document be more than a master's thesis. 1 2 Contents 1 Legal notice 11 2 Introduction 13 2.1 Background . 13 2.1.1 Compilers . 13 2.2 This work . 14 2.2.1 Result . 14 2.2.2 Porting . 14 2.2.3 Restrictions in this document . 14 3 The target system 17 3.1 The target architecture . 17 3.1.1 Registers . 17 3.1.2 Sizes . 18 3.1.3 Addressing modes . 18 3.1.4 Instructions . 19 3.2 The target run-time system and libraries . 21 3.3 Simulation environment . 21 4 The GNU C compiler 23 4.1 The compiler system . 23 4.1.1 The compiler parts . 24 4.2 The porting mechanisms . 25 4.2.1 The C macros: tm.h ..................... 26 4.2.2 Variable arguments . 42 4.2.3 The C file: tm.c ....................... 43 4.2.4 The machine description: md . 43 4.2.5 The building process of the compiler . 54 4.2.6 Execution of the compiler . 57 5 The CRIS port 61 5.1 Preparations . 61 5.2 The target ABI . 62 5.2.1 Fundamental types . 62 3 4 CONTENTS 5.2.2 Non-fundamental types . 63 5.2.3 Memory layout . 64 5.2.4 Parameter passing . 64 5.2.5 Register usage . 65 5.2.6 Return values . 66 5.2.7 The function stack frame . -

In Using the GNU Compiler Collection (GCC)

Using the GNU Compiler Collection For gcc version 6.1.0 (GCC) Richard M. Stallman and the GCC Developer Community Published by: GNU Press Website: http://www.gnupress.org a division of the General: [email protected] Free Software Foundation Orders: [email protected] 51 Franklin Street, Fifth Floor Tel 617-542-5942 Boston, MA 02110-1301 USA Fax 617-542-2652 Last printed October 2003 for GCC 3.3.1. Printed copies are available for $45 each. Copyright c 1988-2016 Free Software Foundation, Inc. Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.3 or any later version published by the Free Software Foundation; with the Invariant Sections being \Funding Free Software", the Front-Cover Texts being (a) (see below), and with the Back-Cover Texts being (b) (see below). A copy of the license is included in the section entitled \GNU Free Documentation License". (a) The FSF's Front-Cover Text is: A GNU Manual (b) The FSF's Back-Cover Text is: You have freedom to copy and modify this GNU Manual, like GNU software. Copies published by the Free Software Foundation raise funds for GNU development. i Short Contents Introduction ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 1 1 Programming Languages Supported by GCC ::::::::::::::: 3 2 Language Standards Supported by GCC :::::::::::::::::: 5 3 GCC Command Options ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 9 4 C Implementation-Defined Behavior :::::::::::::::::::: 373 5 C++ Implementation-Defined Behavior ::::::::::::::::: 381 6 Extensions to -

Latticemico8 Development Tools User Guide

LatticeMico8 Development Tools User Guide Copyright Copyright © 2010 Lattice Semiconductor Corporation. This document may not, in whole or part, be copied, photocopied, reproduced, translated, or reduced to any electronic medium or machine- readable form without prior written consent from Lattice Semiconductor Corporation. Lattice Semiconductor Corporation 5555 NE Moore Court Hillsboro, OR 97124 (503) 268-8000 October 2010 Trademarks Lattice Semiconductor Corporation, L Lattice Semiconductor Corporation (logo), L (stylized), L (design), Lattice (design), LSC, CleanClock, E2CMOS, Extreme Performance, FlashBAK, FlexiClock, flexiFlash, flexiMAC, flexiPCS, FreedomChip, GAL, GDX, Generic Array Logic, HDL Explorer, IPexpress, ISP, ispATE, ispClock, ispDOWNLOAD, ispGAL, ispGDS, ispGDX, ispGDXV, ispGDX2, ispGENERATOR, ispJTAG, ispLEVER, ispLeverCORE, ispLSI, ispMACH, ispPAC, ispTRACY, ispTURBO, ispVIRTUAL MACHINE, ispVM, ispXP, ispXPGA, ispXPLD, Lattice Diamond, LatticeEC, LatticeECP, LatticeECP-DSP, LatticeECP2, LatticeECP2M, LatticeECP3, LatticeMico8, LatticeMico32, LatticeSC, LatticeSCM, LatticeXP, LatticeXP2, MACH, MachXO, MachXO2, MACO, ORCA, PAC, PAC-Designer, PAL, Performance Analyst, Platform Manager, ProcessorPM, PURESPEED, Reveal, Silicon Forest, Speedlocked, Speed Locking, SuperBIG, SuperCOOL, SuperFAST, SuperWIDE, sysCLOCK, sysCONFIG, sysDSP, sysHSI, sysI/O, sysMEM, The Simple Machine for Complex Design, TransFR, UltraMOS, and specific product designations are either registered trademarks or trademarks of Lattice Semiconductor Corporation -

System Calls

System Calls 1 Learning Outcomes • A high-level understanding of System Calls – Mostly from the user’s perspective • From textbook (section 1.6) • Exposure architectural details of the MIPS R3000 – Detailed understanding of the of exception handling mechanism • From “Hardware Guide” on class web site • Understanding of the existence of compiler function calling conventions – Including details of the MIPS ‘C’ compiler calling convention • Understanding of how the application kernel boundary is crossed with system calls in general • Including an appreciation of the relationship between a case study (OS/161 system call handling) and the general case. 2 Operating System System Calls Kernel Level Operating System Requests Applications (System Calls) User Level Applications Applications 3 System Calls • Can be viewed as special function calls – Provides for a controlled entry into the kernel – While in kernel, they perform a privileged operation – Returns to original caller with the result • The system call interface represents the abstract machine provided by the operating system. 4 A Brief Overview of Classes System Calls • From the user’s perspective – Process Management – File I/O – Directories management – Some other selected Calls – There are many more • On Linux, see man syscalls for a list 5 Some System Calls For Process Management 6 Some System Calls For File Management 7 Some System Calls For Directory Management 8 Some System Calls For Miscellaneous Tasks 9 System Calls • A stripped down shell: while (TRUE) { /* repeat forever */