Troubled Waters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gill Nets and Their Operation

Gill Nets and their Operation Saly N. Thomas Central Institute of Fisheries Technology P.O. Matsyapuri, Cochin – 682 029 Email: [email protected] Gill net is a highly selective and passive gear accounting for 20% of all the fishing methods of the world. The simplicity of its design, construction, operation and its low energy requirement make the gear very popular in all the sectors especially in the traditional sector. It is a highly selective gear and the use of this gear in a responsible way ensures resource conservation. The gear is a vertical wall of netting, which is kept erect in water by means of floats and sinkers. The gear is mostly rectangular in shape whose upper end is mounted to a float line (head rope) and the lower end to a sinker line (foot rope). The nets are operated in the surface, column or bottom layers of the water column in inland, coastal and deep sea. Gill nets are operated for the capture of different groups of fishes such as sardine, mackerel, prawn, hilsa, and larger varieties like tuna, shark, seer fish, and other large pelagics. When operated for such larger varieties in the deeper areas of the sea the nets extend to several kilometers. Mechanism of fish capture in gill nets The fact that separates gill nets from all other type of fishing is that in gill nets the `mesh’ of the net serves the dual function of `selecting’ the fish to be caught and catching it. The capture of fish in gill nets depends on the net construction, its dimensions, and the shape of the fish body. -

July 2020 Volume XCVI Number 7

July 2020 Volume XCVI Number 7 Commodore’s Reports Race Results Tennis Fleet New Members July • August 2020 SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY JULY 2 3 4 GALLEY WINDOW BAR RESUMES DECKHANDS LOCKER 1 HOURS NORMAL OPERATING HOURS (JULY 1) Contact Margaret Peebles Bulkhead Race Federal Holiday HAPPY 4th THURS & FRI 4-9p SAT 12-6p at (808) 342-1037 or email Mon-Fri Open 4p Dinghy Race SUNDAY 12-7p Sat Open 10a [email protected] 6p Sharp Start Sun Open 9a (Subject to Change) to make an appointment. 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Deckhands Meeting 6p CG #14 6:30p- TBD Bulkhead Race Dinghy Race 6p Sharp Start ORF Singlehanded CG #17 6:30p - TBD 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Classboat H Mooring 6p F & P 6:30p Bulkhead Race Dinghy Race IRF B-3 6p Sharp Start 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Membership 6p Fleet Ops 6p Bulkhead Race Dinghy Race 6p Sharp Start JR Sailing Session 4 Begins 26 27 28 29 30 31 OFFICE HOURS WED-SUN Classboat B Bulkhead Race Dinghy Race 9a-4p BOD 7p 6p Sharp Start (Subject to Change) SUNDAY MONDAY TUESDAY WEDNESDAY THURSDAY FRIDAY SATURDAY August BAR HOURS OFFICE HOURS 1 WED-SUN Mon-Fri Open 4p 9a-4p Sat Open 10a Sun Open 9a (Subject to Change) 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Deckhands Meeting 6p CG #14 6:30p- TBD Bulkhead Race Dinghy Race 6p Sharp Start CG #17 6:30p - TBD 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Mooring 6p F & P 6:30p Bulkhead Race Dinghy Race 6p Sharp Start 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 Admissions Day Membership 6p Fleet Ops 6p Bulkhead Race Dinghy Race 6p Sharp Start 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 _____________________ ___________________ Bulkhead Race Dinghy Race 30 31 BOD 7p 6p Sharp Start RED = KYC Meeting BLUE = KYC Event / Racing GREEN = Deckhands Locker PURPLE= Holidays Black=Yoga /Revised Hours On the cover: Puanani at anchor in Waimea Bay. -

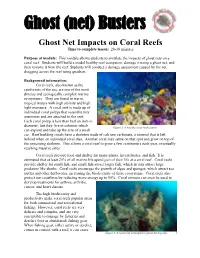

Ghost Net Impacts on Coral Reefs Time to Complete Lesson: 20-30 Minutes

Ghost (net) Busters Ghost Net Impacts on Coral Reefs Time to complete lesson: 20-30 minutes Purpose of module: This module allows students to simulate the impacts of ghost nets on a coral reef. Students will build a model healthy reef ecosystem, damage it using a ghost net, and then remove it from the reef. Students will conduct a damage assessment caused by the net dragging across the reef using quadrats. Background information: Coral reefs, also known as the rainforests of the sea, are one of the most diverse and ecologically complex marine ecosystems. They are found in warm, tropical waters with high salinity and high light exposure. A coral reef is made up of individual coral polyps that resemble tiny anemones and are attached to the reef. Each coral polyp is less than half an inch in diameter, but they live in colonies which Figure 1: A healthy coral reef system. can expand and take up the size of a small car. Reef building corals have a skeleton made of calcium carbonate, a mineral that is left behind when an individual coral dies. Another coral may settle on that spot and grow on top of the remaining skeleton. This allows a coral reef to grow a few centimeters each year, eventually reaching massive sizes. Coral reefs provide food and shelter for many plants, invertebrates, and fish. It is estimated that at least 25% of all marine life spendCredit: part MostBeautifulThings.net of their life at a coral reef. Coral reefs provide shelter for small fish, and small fish attract larger fish, which in turn attract large predators like sharks. -

Another Successful Summer by Nick Mansbach T’S Been So Long Since I’Ve Written but the Clubs to Spend a Fun Filled Day on the Bay

COCONUT GROVE SAILING CLUB channelthe serving the community since 1945 OCTOBER 2008 Another Successful Summer by Nick Mansbach t’s been so long since I’ve written but the clubs to spend a fun filled day on the bay. At about sailing world has been busy, busy, busy! I’ll start 10am we loaded all the parents and all the kids by telling you about this year’s summer camp, on all different kinds of club boats; we had Prams, I Opti’s and Sunfish along with which was a tremendous success. This year we all our powerboats (including had a whopping 213 kids our good ‘ol Pontoon boat) and attending! The reason for headed out to the Dinner Key this dramatic increase was sandbar. If you’ve never seen a our staff; they were by Grandmother sailing in a Pram far the best I’ve ever had with their Granddaughter, let the opportunity to work me tell you it’s quite the sight! with, so thank you to all Once we arrived at the Sandbar the instructors and CIT’s everyone got an opportunity to (counselors in training) sail on all the different boats with who made this possible. their brothers, sisters, moms and We also had our second dads and instructors and CIT’s annual “Parent & kids fun day” which also turned as well. out to be a big hit. We started that morning with During our first hour there we were all treated to approximately 25 parents and about 40 kids looking something pretty cool, the Geico Racing Teams continued on page 8 COMMODORE’S REPORT opefully, by the time you get to read this, autumn will be starting to take hold, and the Hlong hot summer will just about be history. -

Coconut Grove Waterfront Master Plan

COCONUT GROVE WATERFRONT MASTER PLAN ERA / Curtis Rogers / ConsulTech / Paul George Ph.D. Agenda • City's Vision & Community Input • Framework Concepts • December 2006 Schemes • Draft Final Plan – Waterfront Open Space – Civic Core – Maritime Amenities & Facilities – Event Strategy – Roadway Strategy • Next Steps CITY'S VISION & COMMUNITY INPUT City's Vision & Requirements Vision for Coconut Grove's Waterfront • A coastal recreational park • Human scale • Public open space • Connectivity for the pedestrian realm • Waterfront promenades • Diverse open spaces • An active park • Sensitive environmental spoil island connections (real or visual) Requirements • A Plan that reflects the growth and desires of the community • An overhaul of the mooring fields to comply with the Federal Department of Environmental Protection • Spoil islands rehabilitation: cleaned of exotic plants, replanted with native species and redesigned for public access - Coconut Grove Waterfront & Spoil Islands Request for Qualifications Community Input 2004 Peacock Park Charrette • Lead by Friends of Peacock Park to develop a vision for the future of the Peacock Park • Charrette concepts: – Enhance landscaped open spaces – Minimal service parking only – Trim and "window" mangroves – Connection to spoil islands – Tie into local history – Redesign street frontage and articulate entrances – Redesign and seek alternative uses for Glass House – Outdoor cultural facility (amphitheater, waterfront plaza) – Hardcourts ok, no expansion Public Process • Stakeholder Input – May 2005 -

Flyer Jan10.Indd

In thIs Issue January C of C Regatta 1 MAC Wrap up 7 February President’s Column 2 Girls Rule 9 2•0•1•0 2010 Race Dates 4 Opposite Tack 10 MidWinters 5 Fleet 39 11 Helmsman 6 Classified 12 2009 ChampIonshIp of ChampIons A Publication of the American Y-Flyer Yacht Racing Association Regatta By Paul White Y-2782 Each year, a one-design sailboat is chosen to be raced in the Championship of Champions Regatta, also known as the C of C. This year, US Sailing Event Chairman, Drew Daugherty, selected the Lightning sailboat and asked the Carlyle Sailing Association to host the event. Twenty skippers, who are the reigning National, International, or North American Champions of their respective classes, are invited to compete. As the reigning Y-Flyer International Champion, I was invited to represent our class. The regatta was managed with precision by Drew Daugherty and Regatta Chairman, Matt Burridge, as well as a cadre of volunteers. The regatta began Wednesday morning with registration and a Lightening overview, including sailing tips, for my crew, Pat Passafiume and Steve Roeschlein, and myself. The remainder of Wednesday was spent honing our skills with several hours of practice racing and sailing. The afternoon practice races brought winds from the north in the low teens, white capping waters and air temperatures in the mid 40’s with a very cloudy and gray sky. The practice race course was approximately nine-tenths of a mile to windward, a mile to a leeward gate, and one- tenth of a mile upwind to the finish. -

Impact of “Ghost Fishing“ Via Derelict Fishing Gear

2015 NOAA Marine Debris Program Report Impact of “Ghost Fishing“ via Derelict Fishing Gear 2015 MARINE DEBRIS GHOST FISHING REPORT March 2015 National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Ocean Service National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science – Center for Coastal Environmental Health and Biomolecular Research 219 Ft. Johnson Rd. Charleston, South Carolina 29412 Office of Response and Restoration NOAA Marine Debris Program 1305 East-West Hwy, SSMC4, Room 10239 Silver Spring, Maryland 20910 Cover photo courtesy of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration For citation purposes, please use: NOAA Marine Debris Program. 2015 Report on the impacts of “ghost fishing” via derelict fishing gear. Silver Spring, MD. 25 pp For more information, please contact: NOAA Marine Debris Program Office of Response and Restoration National Ocean Service 1305 East West Highway Silver Spring, Maryland 20910 301-713-2989 Acknowledgements The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Marine Debris Program would like to acknowledge Jennifer Maucher Fuquay (NOAA National Ocean Service, National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science) for conducting this research, and Courtney Arthur (NOAA National Ocean Service, Marine Debris Program) and Jason Paul Landrum (NOAA National Ocean Service, Marine Debris Program) for providing guidance and support throughout this process. Special thanks go to Ariana Sutton-Grier (NOAA National Ocean Science) and Peter Murphy (NOAA National Ocean Service, Marine Debris Program) for reviewing this paper and providing helpful comments. Special thanks also go to John Hayes (NOAA National Ocean Service, National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science) and Dianna Parker (NOAA National Ocean Science, Marine Debris Program) for a copy/edit review of this report and Leah L. -

Design a Safe Fishing Net Notes for Teachers

You need: Design a safe • Paper or card • Pencils • Colouring pens fishing net or pencils Thousands of whales and dolphins die every year because they get trapped in fishing nets. They can’t get to the surface to breathe, so they suffocate and drown. How can we design nets that can catch fish, but won’t accidentally catch whales and dolphins? Each child will need some 1 paper, a pencil and some colouring supplies. Their challenge is to design a net that will successfully catch fish, but won’t catch whales and dolphins. Encourage children to think about what they’ve learnt about whales 2 and dolphins that might help them with their designs, for example: • How do dolphins find their food? • How big are whales and dolphins? Scan or take photos of the best net designs and send them to [email protected] – we’d love to see them! Design a safe fishing net Notes for teachers Ask the children questions to encourage them to think about their designs. Their solutions might involve stopping whales and dolphins from swimming into the net in the first place, or ways to escape if they do get trapped. Some great ideas from other children have included: • Brightly coloured nets that are easily seen; • Nets that make noise to scare whales and dolphins away; • Sensors that detect if a whale or dolphin is nearby, then retract the net; • Monitored cameras so fishermen can see and release a trapped whale or dolphin; • Nets that do not close if a whale or dolphin, or the weight of a whale or dolphin, is detected. -

Bassculture Islands Bassculture Islands

BASSCULTURE ISLANDS BASSCULTURE ISLANDS Featured photographer: Donn Thompson Model: Sarah Sebit 2. basscutlture islands BASSCULTURE ISLANDS BASSCULTURE #11 THE BAHAMAS ISLANDS my personal ISSUE #11 dharma - ART IN FOCUS Travel entrepreneur 28 36 editor’s note Lately I have been reminiscing the time when I traveled and made EDITOR IN CHIEF home of few different places in the world. I loved the feeling of being Ania Orlowska BAHAMAS love for the ocean in a new place and getting to know local people and local spots and MUST-DO LIST - diving in just dive into the culture . Only then I was able to say that I have CREATIVE DIRECTION/ the bahamas traveled and discovered. For this reason today I can totally relate to GRAPHIC DESIGN the island hopper - Jamie Werner who lived on so many different Kerron Riley 12 Caribbean islands and is able to give tips to all the travellers visiting Ania Orlowska 44 The Bahamas. Don’t miss her travel tips! I can also relate to entre- FILM EDITOR UNDERWATER preneur Monica Walton as she describes the road she took to be all about Emiel Martens PASSION - successful and the fact that the road is usually bumpy. As a creative film makers INSPIRATION entrepreneur and talent agent I can definitely appreciate the beauti- PROJECT EXECUTION ful art of Danielle Boodoo-Fortuné and Giovani Zanolino. And even theOrlowska Agency though I have never done any diving, I share the love for the ocean www.theorlowska.com 20 64 with Bahamian diver Andre Musgrove. Watch how he is giving some really nice tips for both divers and visitors to the Bahamas. -

Marine Advisory China Fishing Vessels 03-2017.Pdf

8619 Westwood Center Drive Suite 300 THE REPUBLIC OF LIBERIA Vienna, Virginia 22182, USA Tel: +1 703 790 3434 LIBERIA MARITIME AUTHORITY Fax: +1 703 790 5655 Email: [email protected] Web: www.liscr.com 16 May 2017 Marine Advisory: 03/2017 SUBJECT: Precautions when Navigating Waters in and around Ningbo-Zhoushan, China Dear Owner, Operator, Master and Designated Person Ashore: Purpose The purpose of this Advisory is to bring attention to recent collisions involving Chinese fishing and Liberian flagged vessels and provide additional information to assist Master’s in safely navigating highly congested waters off Ningbo-Zhoushan in the East China Sea. These collisions occurred mostly at night or in fog conditions where visibility was restricted and additional lookouts were not engaged. Discussion The Chinese port Port of Ningbo-Zhoushan is located in Ningbo and Zhoushan on the coast of the East China Sea, in Zhejiang province and is ranked the busiest cargo port in the world. Large fleets of fishing junks may be encountered on the coast of China. The junks may not be carrying lights. They are solidly built and serious damage could be incurred by colliding with them. Fishing vessels vary from traditional rowing or sailing craft as little as 3m long to modern trawlers 15m long and over. We recently met with China Maritime Safety Administration (MSA) to review the collision cases and explore possible measures to help prevent similar casualties and loss of life. Attached is an Advisory prepared by Ningbo MSA that provides guidance for Master’s on navigating through the East China Sea and areas where there may be high concentrations of fishing vessels. -

ECONOMIC VALUE of RECREATIONAL FISHING to RHODE ISLAND HAS INCREASED Value Now More Than Commercial Fishing

www.RISAA.org JUNE, 2017 • Issue 222 401-826-2121 Representing Over 7,500 Recreational Anglers Updated NOAA report... ECONOMIC VALUE OF RECREATIONAL FISHING TO RHODE ISLAND HAS INCREASED Value now more than commercial fishing Recreational fishing appeals to our sense of adventure and builds a lifetime of memories with family and friends. It is also important to the Rhode Island economy! (See story on page 16) Proposed changes to coastal management of tautog States Schedule Hearings on Draft Amendment 1 The Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission (ASMFC) has announced that the states of Massachusetts through Virginia have scheduled hearings to gather public comment on Draft Amendment 1 to the Interstate Fishery Management Plan (FMP) for Tautog. The Draft Amendment proposes a fundamental change in tautog management, moving away from management on a coastwide basis towards regional management. In addition, Draft Amendment 1 proposes the establishment of a commercial harvest tagging program, as well as new goals and objectives, biological reference points and fishing mortality targets, and a stock rebuilding schedule. Specifically, Draft Amendment 1 proposes delineating the stock into four regions due to differences in biology and fishery characteristics, as well as limited coastwide movement. (to page 37) R.I.S.A.A. / May, 2017 Public access must be a never ending fight It was disappointing last month to learn The case, Peter Kilmartin, Attorney June 3 • 10:00 AM Kayak Committee that the Rhode Island Supreme Court General of the State of Rhode Island vs Annual Meet & Greet, Goddard Park would not overturn the lower court ruling Joan M. -

Hawaii Administrative Rules Title 13 Department of Land

HAWAII ADMINISTRATIVE RULES TITLE 13 DEPARTMENT OF LAND AND NATURAL RESOURCES SUBTITLE 4 FISHERIES PART II MARINE FISHERIES MANAGEMENT AREAS CHAPTER 47 HILO BAY, WAILOA RIVER AND WAILUKU RIVER, HAWAII §13-47-1 Definitions §13-47-2 Prohibited activities §13-47-3 Permitted activities §13-47-4 Penalty Historical Note. Chapter 47 of Title 13 is based substantially upon Regulation 35 of the Division of Fish and Game, Department of Land and Natural Resources, State of Hawaii. [Eff 3/23/70; am 11/22/73; R 5/26/81] §13-47-1 Definitions. As used in this chapter unless otherwise provided: “Hilo Harbor” means the waters of that portion of the bay in Hilo bounded by the breakwater, thence along a line from the tip of the breakwater southwestward to Alealea Point, then along the shoreline to the inshore end of the breakwater as delineated in “Locations and Landmarks of Hilo Harbor, Wailoa River and Wailuku River, Hawaii 11/12/87” attached at the end of this chapter. “Moi” means any fish known as Polydactylus sexfilis or a recognized synonym. Also known as, among other names, moi li’i, mana moi, pala moi, pacific threadfin, and six-fingered threadfin. “Mullet” means any fish known as Mugil cephalus or a recognized synonym. The young of this species are known as, among other names, pua ama’ama, pua, po’ola, and o’ola. Also known as, among other names, ama’ama, 47-1 §13-47-1 anae, anaeholo, anaepali, gray mullet and striped mullet. “Netting” means the taking or killing of fish by means of any net except throw nets, opae/dip nets, crab nets, and nehu nets.