True (Kantian?) Detective. Fighting Illusion with Disillusion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Untitled Spreadsheet

Priority sector for Name of the project in Summary of the project in English, including goal and results (up Full name of the applicant Total project budget Requested amount ID Competition program LOT Type of project culture and arts English to 100 words) organization in English (in UAH) from UCF (in UAH) The television program is based on facts taken from historical sources, which testify to a fundamental distortion of the history of the Russian Empire, aimed at creating a historical mythology that Muscovy and Kievan Rus have common historical roots, that Muscovy has "inheritance rights" on Kievan Rus. The ordinary fraud of the Muscovites, who had taken possession of the past of The cycle of science- the Grand Duchy of Kiev and its people, dealt a terrible cognitive television blow to the Ukrainian ethnic group. Our task is to expose programs "UKRAINE. the falsehood and immorality of Moscow mythology on Union of STATE HISTORY. Part the basis of true facts. Without a great past, it is impossible Cinematographers "Film 3AVS11-0069 Audiovisual Arts LOT 1 TV content Individual Audiovisual Arts I." Kievan Rus " to create a great nation. Logos" 1369589 1369589 New eight 15-minute programs of the cycle “Game of Fate” are continuation of the project about outstanding historical figures of Ukrainian culture, art and science. The project consists of stories of the epistolary genre and memoirs. Private world of talented personalities, complex and ambiguous, is at the heart of the stories. These are facts from biographies that are not written in textbooks, encyclopedias, or wikipedia, but which are much more likely to attract the attention of different audiences. -

PHED Committee in January

PHED ITEM #3 January 25, 2021 Worksession M E M O R A N D U M January 20, 2021 TO: Planning, Housing, and Economic Development (PHED) Committee FROM: Gene Smith, Legislative Analyst SUBJECT: Review of Pandemic-related Business Assistance Programs PURPOSE: Discussion, no votes expected Those expected for this worksession: Jerome Fletcher, Office of the County Executive Laurie Boyer, Office of the County Executive Ben Wu, Montgomery County Economic Development Corporation (MCEDC) Bill Tompkins, MCEDC Sarah Miller, MCEDC The PHED committee requested a review of all the business assistance programs implemented by the County in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Program implementation was divided between the County and the MCEDC. I. Background and Summary The COVID-19 pandemic has created an uneven recession with certain industry sectors more impacted than others. Hospitality, leisure, restaurants, and retail businesses have seen the largest decline in economic activity. Much of this decline is due to the State and County health orders that restrict gathering size to limit the spread of the virus. While there was some expectation that the health orders and restrictions would be short-term measures, the reality is the pandemic has required that these orders remain in place for many months. The Council created many new business assistance programs for the impacted industry sectors to respond to this uneven recession. These new programs were funded and administered by the County or its partners. This memo provides a summary for each program implemented and includes detailed program information in the attachments. Table 1 provides an overview of all the programs included in this report. -

Who Watches the Watchmen? the Conflict Between National Security and Freedom of the Press

WHO WATCHES THE WATCHMEN WATCHES WHO WHO WATCHES THE WATCHMEN WATCHES WHO I see powerful echoes of what I personally experienced as Director of NSA and CIA. I only wish I had access to this fully developed intellectual framework and the courses of action it suggests while still in government. —General Michael V. Hayden (retired) Former Director of the CIA Director of the NSA e problem of secrecy is double edged and places key institutions and values of our democracy into collision. On the one hand, our country operates under a broad consensus that secrecy is antithetical to democratic rule and can encourage a variety of political deformations. But the obvious pitfalls are not the end of the story. A long list of abuses notwithstanding, secrecy, like openness, remains an essential prerequisite of self-governance. Ross’s study is a welcome and timely addition to the small body of literature examining this important subject. —Gabriel Schoenfeld Senior Fellow, Hudson Institute Author of Necessary Secrets: National Security, the Media, and the Rule of Law (W.W. Norton, May 2010). ? ? The topic of unauthorized disclosures continues to receive significant attention at the highest levels of government. In his book, Mr. Ross does an excellent job identifying the categories of harm to the intelligence community associated NI PRESS ROSS GARY with these disclosures. A detailed framework for addressing the issue is also proposed. This book is a must read for those concerned about the implications of unauthorized disclosures to U.S. national security. —William A. Parquette Foreign Denial and Deception Committee National Intelligence Council Gary Ross has pulled together in this splendid book all the raw material needed to spark a fresh discussion between the government and the media on how to function under our unique system of government in this ever-evolving information-rich environment. -

Smaller Ballers Class Description | Pg

Winter/Spring 2017 January - April Smaller Ballers Class Description | pg. 6 Open Registration Begins Monday, December 5, 8:00am City of Olympia | Parks, Arts & Recreation | olympiawa.gov/parks Art for All Ages Grow With Us Photographer Mary Randlett with an exhibition of her work at Arts Walk. What’s Inside Director Paul Simmons’ Welcome Great move on opening this guide to recreation in Olympia! Inside you will find so many awesome activities for you, your family or your friends. Whether your pursuit is in the area of art, fitness and health, or cultural learning; I know you can find something that will enhance your quality of life. The Olympia Parks, Arts and Recreation Department is excited to make this winter a great experience for you and we are eager to help you get connected with us! Give us a call today (as long as it isn’t Sunday) and let’s get started! Events, Trips & Tours 4 Gentle Holistic Yoga ~ page 25 Park Stewardship Spring Arts Walk Snow Shoe Trip Earth Day Stewardship Event Nisqually Delta Kayak Trip Community Gardens Preschool 5 Family Playtime Martial Arts Preschool By The Bay Gymnastics Music & Movement Kidz Love Soccer Smaller Ballers Youth & Teen 8 Coding With Kids Magic Tricks & Secrets Bricks 4 Kidz Martial Arts Super Sitters Gymnastics Safe at Home Kidz Love Soccer Mosaic Fun Winter/Spring Break Camps Adult 14 Banquet Rentals Cooking Fitness, Mind & Body at The Olympia Center ~ page 31 Dance & Music Golf Classes Fine Art & Crafts Sports Leagues Essential Oils Open Gyms Specialty Classes Tournaments Information 28 Parks Information Boards & Commissions Facility & Shelter Rentals Contact Information The “Details” Sign-up Information Become an Instructor Essential Oil Classes ~ page 21 Satisfaction Guaranteed Unless otherwise noted, If for any reason you are unhappy with all classes and programs a class we will refund your money, will be held at.. -

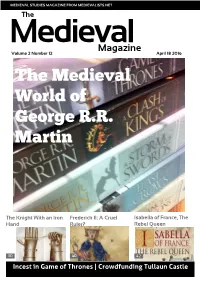

The Medieval World of George R.R. Martin

MEDIEVAL STUDIES MAGAZINE FROM MEDIEVALISTS.NET The Medieval Magazine Volume 2 Number 12 April 18 2016 The Medieval World of George R.R. Martin The Knight With an Iron Frederick II: A Cruel Isabella of France, The Hand Ruler? Rebel Queen 30 40 42 Incest in Game of Thrones | Crowdfunding Tullaun Castle The Medieval Magazine April 18, 2016 Page 10 Crowdfunding for Tullaun Castle See how the owners of this Irish castle are seeking to raise money for its restoration. Page 12 Incest in Game of Thrones Nancy Bilyeau examines the historical inspirations for incestuous relationships in A Song of Ice and Fire. Page 26 A Hard Day's Knight Daniele Cybulskie compares knighthood between medieval Europe and Westeros. Page 40 Cruel Tyrant: The Reign of Frederick II Sandra Alvarez takes a look at the 'scientific' experiments carried out by the Holy Roman Emperor Table of Contents 4 Brief encounters: watching medieval archaeology emerge from the heart of Perth 8 The King Richard III Skull Portraits 10 Crowdfunding Campaign for Tullaun Castle 12 Incest in Game of Thrones 17 Game of Thrones: Hierarchy and Violence 18 Winter is Coming - An Interview with Carolyne Larrington 23 What Mongol History Predicts for the next season of Game of Thrones 26 A Hard Day's Knight 30 The Knight with an Iron Hand 33 Game of Thrones and the fluid world of medieval gender 37 Why hasn't Westeros had an industrial revolution? 40 Cruel Tyrant: The Reign of Frederick II 42 Book Excerpt: Isabella of France: The Rebel Queen THE MEDIEVAL MAGAZINE Editor: Peter Konieczny Website: www.medievalists.net This digital magazine is published each Monday. -

Student Liberal Arts Mosaic . . . Research, Performance, and Creativity

Student Liberal Arts Mosaic . Research, Performance, and Creativity 1 Student Liberal Arts Mosaic . Research, Performance, and Creativity Order of Ceremonies In the One Hundred Sixty Fourth Year of Mars Hill University April 21, 2020 Online via Zoom The Fanfare: 10:30 A.M. MHU Percussion Ensemble Performance from SLAM 2019 & other recent years’ performances Dr. Brian Tinkel and Mr. Justin Mabry, directors Opening Celebration: 10:45-11:00 A.M. The Invocation Ryan Davis SLAM Committee Student Representative The President’s Welcome President Tony Floyd Welcome from the SLAM Committee & Overview of SLAM Mrs. Joy Clifton SLAM Committee Chair 2 Student Liberal Arts Mosaic . Research, Performance, and Creativity PLENARY Session 11:00 – 11:45 A.M. Introduction of the Speaker Fajhenee Bradford SLAM Committee Student Representative Ed Mabrey Ed Mabrey, actor, author, and speaker, exemplifies the modern-day renaissance artist. From the page to the stage and the script to the screen, Ed captivates, motivates, and promulgates the performing arts. He is the winningest poet in the history of Poetry Slam—4 World Championships, 5 consecutive Regional Championships, and over 500 wins in his career. Ed tours the country professionally as a poet, comedian, and professional speaker. Also, an Emmy award winner, Ed has been on Seasons 3, 5, and 6 of Verses and Flow (TV One), as well as appearing on broadcasts on ABC, FOX, HBO All Def Digital, Crackle, CNN, and C-SPAN. Ed was a speaker at 2015 TEDx Dayton and 2017 TEDx Evans Street. As the 2019 APCA Spoken Word Artist of the Year, Ed has performed at over 100 colleges and universities around the country teaching workshops and conducting seminars. -

Mosaic Spring 2017

FISCHLOWITZ TRAVEL FELLOWSHIP............................................................................ 27 STUDY ABROAD TABLE OF MES AVENTURES EN SUISSE .............................................................................. 29 THE LESSONS OF DISSONANCE ....................................................................... 31 CONTENTS WHERE DID YOU STUDY ABROAD? ................................................................ 32 THEY STUDIED ABROAD TOO! ..........................................................................33 OLYMPICS LIVING THE OLYMPIC DREAM .............................................................. 3 MY RIO STORY........................................................................................... 5 EDITOR'S TEACHERS FOR A DAY ...................................................................................... 8 NOTE Han Trinh '17 COVER ART Josh Anthony '17 IDENTITY AND DIVERSITY MOSAIC Editor 2016-17 FINDING MY IDENTITY .............................................................................. 9 It has been my pleasure to be the editor of this year's issue of MOSAIC mag THE STATE OF BELONGING .................................................................... 11 azine. I was super excited to be editor of a magazine - the power! It was hard ENGLISH AND IDENTITY ..........................................................................13 sometimes - InDesign doesn't always like me, I felt bad for bugging people for articles... but it was a great experience. Reading and editing such interest -

A Mosaic of Practices PUBLIC MEDIA and PARTICIPATORY

A MOSAI C O F PRA C TI C ES : PUBLIC MEDIA AND PARTICIPATORY CULTURE Once the Wexner Center for the Arts in Columbus, Ohio, had approved together was the group’s participatory and largely fluid nature as a my proposal to begin a planned seven-year process of making a community, operating completely under and around official university documentary about a group of women majoring in the sciences and culture. The students allowed me to glimpse their all-consuming technology at Ohio State University (OSU), it occurred to me that I was undergraduate lives and eagerly took part in the forums and variety of going to have to do more than just show up in their dorms and classrooms interview and dialogue situations I devised. with a camera crew a few times a year until they graduated. After many individual meetings with interested freshman students with whom I’d Even though they couldn’t articulate it at the time, the women at OSU been connected through the University Honors Program, I invited several seemed extremely interested to momentarily consider glimpses of AFTERIMAGE young women to consider taking part in the film project. Before they left the longer view of how, why, and what they were striving for in their school that summer, I recorded interviews with each of them, posing the respective fields, as well as any personal change or growth they were question, “When you look back at your childhood, what brought you to experiencing in the university environment. Even though we didn’t talk 35.6 your interest in science, technology, engineering, and math?” about the form and function of the group itself, it became clear during our first year together that the Gender Chip Project was becoming an We started meeting in the fall of 1998, at the start of the young important part of their lives. -

GAME of THRONES FILM SETTINGS Where Was Game of Thrones Filmed in Spain You Ask? We've Got the Answer

EXAMPLE ITINERARY GAME OF THRONES FILM SETTINGS Where was Game of Thrones filmed in Spain you ask? We've got the answer... The epically popular Game of Thrones took over where Lord of the Rings left off; once a huge draw for visitors to tour New Zealand in search of LOR filming locations, nowadays it’s Europe that’s drawing the fans. Filmed throughout various regions of Spain, Game of Thrones was TV's most ambitious project in years and it was also the show that had (and still has) people talking about it all around the world; more than any other TV drama. If you love HBO’s epic medieval drama, Game of Thrones, and want to visit some of the many film locations* while you discover the real Spain at the same time, this tailor-made tour might just be for you! Although the series has ended, it doesn’t mean we’re done with Game of Thrones… * There are, of course, many more Game of Thrones filming locations in Spain besides the ones which appear in this itinerary and if you need more, we would be happy to include these in your tailor made itinerary. Please refer to the end of this itinerary for a complete list of these locations. SUMMARY (12 nights) What’s Included? What’s not Included? Start: Madrid All private transfers International Air Flights End: Barcelona Boutique 4/5-star hotels Travel/medical Insurance 2 N Madrid Breakfasts & all meals mentioned Meals & Drinks, other than in the itinerary those mentioned in the 2 N Cordoba (Long Bridge of Volantis, Highgarden) itinerary Guided tours with fluent English 2 N Sevilla (The Water Gardens of Dorne, Dragonpit) speaking guides. -

LESDEUXNOIRS-STUDY-GUIDE.Pdf

By PSALMAYENE 24 Directed by RAYMOND O. CALDWELL STUDY GUIDE SEASON FOUR Introduction “Theatre is a form of knowledge; it should and can also be a means of transforming society. Theatre can help us build our future, rather than just waiting for it.”—Augusto Boal The purpose and goal of Mosaic’s education department is simple. Our program aims to further and cultivate students’ knowledge and passion for theatre and theatre education. We strive for complete and exciting arts engagement for educators, artists, our community, and all learners in the classroom. Mosaic’s education program yearns to be a conduit for open discussion and connection to help students understand how theatre can make a profound impact in their lives, in society, and in their communities. Mosaic Theater Company of DC is thrilled to have your interest and support! Catherine Chmura Arts Education Apprentice—Mosaic Theater Company of DC Written by Catherine Chmura & Isaiah M. Wooden 2 LES DEUX NOIRS MOSAIC THEATER COMPANY of DC PRESENTS LES DEUX NOIRS NOTES ON NOTES OF A NATIVE SON By Psalmayene 24 Directed by Richard O. Caldwell Choreographer: Tiffany Quinn Set Designer: Ethan Sinnott Lighting Designer: William Kendall D’Eudenio Costume Designer: Amy MacDonald Sound Designer: Nick Hernandez Projections Designer: Dylan Uremovich Properties Designer: Willow Watson Production Stage Manager: April E. Carter Dramaturg: Isaiah M. Wooden & Khalid Yaya Long Table of Contents Curriculum Connections: DC Public School ................................ 4 DCPL Reading List ........................................................................... -

The Loudest Roar

’06 SESAME WORKSHOP 2006 ANNUAL REPORT SESAME WORKSHOP 2006 ANNUAL REPORT THE LOUDEST ROAR [ The potential for Sesame Street in India to make a positive change is enormous: 128 million children between the ages of 2 and 6 live in India and two-thirds lack access to early childhood care and education. ] DEPLOYING ELMO: UPSIDE DOWN: HELP FOR FAMILIES ABSTRACT THINKING DURING MILITARY GOES TO THE GYM DEPLOYMENT NEW ACTIVITIES IN WORD ON THE STREET: THE MIDDLE EAST NEW DIRECTIONS IN LITERACY LEARNING Galli Galli Sim Sim Mobile Community Viewing event, Dakshinpuri, Delhi President’s Letter Chamki INDIA Whether the “loudest roar” emanates from Boombah, the friendly lion of our newest Sesame Street coproduction in India, or one of the many other characters in Sesame Workshop’s global family, the message is the same: Educate a child; change the world. Sesame Workshop 2006 Annual Report 03 President’s Letter Educate a child, change the world — We’re talking ment reaches far beyond its own television audiences, about social change through Muppets, through songs and Miditech Pvt. Ltd., a gifted local production and stories children love and parents trust. We’re company,to launch Galli Galli Sim Sim on television joined around the world in this effort by unlikely (public, cable, and satellite) and through educational coalitions of government ministers, corporate leaders, outreach. This simultaneous launch was a first for us and social activists. Why? Because we all hope for a internationally and a strong testament to a shared better future, and that future begins with children. vision of reaching children in need. -

Heitur Réttur Í Hádeginu

Kíktu á HEITUR RÉTTUR BRÚÐKAUP heimasíðu okkar 1041 0966 2019 www.heradsprent.is Í HÁDEGINU BORÐAÐU Á STAÐNUM EÐA TAKTU MEÐ OPIÐ ALLA DAGA 8 - 23 1.-2. tbl. 25. árg. Vikan 10.-16. janúar 2019 ✆ 471 1449 - [email protected] - www.heradsprent.is útsala Útsala er hafin í Fjarðasporti og Veiðiflugunni. Frábærar vörur á 30 og 50% afslætti. Fatnaður og skór. Minnum á að frábært er að nota GJAFABRÉFIN til kaupa á útsöluvörum. …allan sólarhringinn Neskaupstað Sími 477 1133 SUMARSTÖRF Á EGILSSTÖÐUM Egilsstaðastofa og Tjaldsvæðið á Egilsstöðum leitar að starfsfólki fyrir sumarið 2019. Um er að ræða lifandi og skemmtilegt starf við afgreiðslu, upplýsingagjöf og þrif. Leitað er að drífandi og skipulögðum einstaklingum Egilsstaðastofu er ætlað að styrkja og ea markaðsstarf á Fljótsdalshéraði. Á sumrin er aðal áherslan lögð á að með framúrskarandi þjónustulund. veita upplýsingar um Héraðið sem áfangastað ferðamanna og verslunar- og þjónustumiðstöð. Hæfniskröfur Á Egilsstaðastofu má nna almenningssalerni og sturtur, þvottavélar og þurrkara, vörur af Héraði og stór bílastæði • Góð þekking á staðháttum á Fljótsdalshéraði og Austurlandi fyrir rútur sem og aðra bíla. • Mjög góð íslensku- og enskukunnátta skilyrði (eiri tungumál kostur) Egilsstaðastofa og Tjaldsvæðið á EGS er • Sjálfstæð vinnubrögð OPIÐ ALLAN ÁRSINS HRING! Möguleiki er að semja um að hea og enda störf á skemmri eða lengri tíma yr sumarmánuðina. Umsóknarfrestur er til 20. mars 2019. Umsóknir ásamt ferilskrá skal senda á [email protected]. Austurför ehf. - Kaupvangur 17 - 700 Egilsstaðir - ✆ 4 700 750 - Netfang: [email protected] Spennandi atvinnutækifæri í Fjarðabyggð Fjölskyldusvið Fjarðabyggðar leitar eftir að ráða kraftmikla og drífandi einstaklinga í eftirfarandi störf.