Comparative Molecular Cytogenetic Characterization of Five Wild Vigna Species (Fabaceae)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL DE CAMPINAS Instituto De Biologia

UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL DE CAMPINAS Instituto de Biologia TIAGO PEREIRA RIBEIRO DA GLORIA COMO A VARIAÇÃO NO NÚMERO CROMOSSÔMICO PODE INDICAR RELAÇÕES EVOLUTIVAS ENTRE A CAATINGA, O CERRADO E A MATA ATLÂNTICA? CAMPINAS 2020 TIAGO PEREIRA RIBEIRO DA GLORIA COMO A VARIAÇÃO NO NÚMERO CROMOSSÔMICO PODE INDICAR RELAÇÕES EVOLUTIVAS ENTRE A CAATINGA, O CERRADO E A MATA ATLÂNTICA? Dissertação apresentada ao Instituto de Biologia da Universidade Estadual de Campinas como parte dos requisitos exigidos para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Biologia Vegetal. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Fernando Roberto Martins ESTE ARQUIVO DIGITAL CORRESPONDE À VERSÃO FINAL DA DISSERTAÇÃO/TESE DEFENDIDA PELO ALUNO TIAGO PEREIRA RIBEIRO DA GLORIA E ORIENTADA PELO PROF. DR. FERNANDO ROBERTO MARTINS. CAMPINAS 2020 Ficha catalográfica Universidade Estadual de Campinas Biblioteca do Instituto de Biologia Mara Janaina de Oliveira - CRB 8/6972 Gloria, Tiago Pereira Ribeiro da, 1988- G514c GloComo a variação no número cromossômico pode indicar relações evolutivas entre a Caatinga, o Cerrado e a Mata Atlântica? / Tiago Pereira Ribeiro da Gloria. – Campinas, SP : [s.n.], 2020. GloOrientador: Fernando Roberto Martins. GloDissertação (mestrado) – Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Instituto de Biologia. Glo1. Evolução. 2. Florestas secas. 3. Florestas tropicais. 4. Poliploide. 5. Ploidia. I. Martins, Fernando Roberto, 1949-. II. Universidade Estadual de Campinas. Instituto de Biologia. III. Título. Informações para Biblioteca Digital Título em outro idioma: How can chromosome number -

![Genus Vigna and Cowpea (V. Unguiculata [L.] Walp.) Taxonomy: Current Status and Prospects](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6009/genus-vigna-and-cowpea-v-unguiculata-l-walp-taxonomy-current-status-and-prospects-2336009.webp)

Genus Vigna and Cowpea (V. Unguiculata [L.] Walp.) Taxonomy: Current Status and Prospects

Genus Vigna and Cowpea (V. unguiculata [L.] Walp.) taxonomy: current status and prospects R.S. Pasquet1* and S. Padulosi2 1ICIPE, PO Box 30772, Nairobi, Kenya 2Bioversity International,Via dei Tre Denari, Maccarese (Rome), Italy *Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract Since the mid-nineties, thanks to DNA sequence studies, phylogeny of Phaseoleae, Phaseolinae, and genus Vigna has been greatly improved. Genus Vigna is now reduced to a monophyletic group including five reorganized subgenera: American subgenus Lasiospron, a subgenus Vigna reduced to yellow and blue-flowered species which includes Bambara groundnut, subgenus Haydonia, Asian subgenus Ceratotropis, and a subgenus Plectrotropis enlarged to all pink-flowered species. At the infraspecific level, although a precise phylogeny is not yet established, the different wild and domesticated cowpea groups are now well known. The nine subspecies can be split between a “mensensis” forest group (remote secondary gene pool) and a “dekindtiana” savanna group (close secondary gene pool) which includes subsp. unguiculata. Subsp. unguiculata represents the primary gene pool and includes the domesticated cowpea, var. unguiculata, and its wild progenitor, var. spontanea (previously known as subsp. dekindtiana sensu Verdcourt non Harms). However, if cowpea domestication occurred before 1500 BC in Harlan’s African non-center, a precise center of domestication is yet to be identified. Introduction Over the last 30 years, cowpea and Vigna taxonomy has been reviewed by several workers, including Baudoin and Maréchal (1985), Ng and Maréchal 1985, Pasquet 1996a, Pasquet 1996b, and Padulosi and Ng (1997) with substantial improvement. It is however particularly from the mid-nineties onward, that novel molecular technologies applied to taxonomy, such as DNA finger printing, have provided major advancement on the front of the phylogeny of Phaseoleae, Phaseolinae, and genus Vigna. -

A New Subfamily Classification of The

LPWG Phylogeny and classification of the Leguminosae TAXON 66 (1) • February 2017: 44–77 A new subfamily classification of the Leguminosae based on a taxonomically comprehensive phylogeny The Legume Phylogeny Working Group (LPWG) Recommended citation: LPWG (2017) This paper is a product of the Legume Phylogeny Working Group, who discussed, debated and agreed on the classification of the Leguminosae presented here, and are listed in alphabetical order. The text, keys and descriptions were written and compiled by a subset of authors indicated by §. Newly generated matK sequences were provided by a subset of authors indicated by *. All listed authors commented on and approved the final manuscript. Nasim Azani,1 Marielle Babineau,2* C. Donovan Bailey,3* Hannah Banks,4 Ariane R. Barbosa,5* Rafael Barbosa Pinto,6* James S. Boatwright,7* Leonardo M. Borges,8* Gillian K. Brown,9* Anne Bruneau,2§* Elisa Candido,6* Domingos Cardoso,10§* Kuo-Fang Chung,11* Ruth P. Clark,4 Adilva de S. Conceição,12* Michael Crisp,13* Paloma Cubas,14* Alfonso Delgado-Salinas,15 Kyle G. Dexter,16* Jeff J. Doyle,17 Jérôme Duminil,18* Ashley N. Egan,19* Manuel de la Estrella,4§* Marcus J. Falcão,20 Dmitry A. Filatov,21* Ana Paula Fortuna-Perez,22* Renée H. Fortunato,23 Edeline Gagnon,2* Peter Gasson,4 Juliana Gastaldello Rando,24* Ana Maria Goulart de Azevedo Tozzi,6 Bee Gunn,13* David Harris,25 Elspeth Haston,25 Julie A. Hawkins,26* Patrick S. Herendeen,27§ Colin E. Hughes,28§* João R.V. Iganci,29* Firouzeh Javadi,30* Sheku Alfred Kanu,31 Shahrokh Kazempour-Osaloo,32* Geoffrey C. -

WO 2017/202946 Al 30 November 2017 (30.11.2017) W !P O PCT

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2017/202946 Al 30 November 2017 (30.11.2017) W !P O PCT (51) International Patent Classification: Published: C12N 9/5 (2006.01) — with international search report (Art. 21(3)) (21) International Application Number: — before the expiration of the time limit for amending the PCT/EP2017/062598 claims and to be republished in the event of receipt of amendments (Rule 48.2(h)) (22) International Filing Date: — with sequence listing part of description (Rule 5.2(a)) 24 May 2017 (24.05.2017) (25) Filing Language: English (26) Publication Langi English (30) Priority Data: 16170964.7 24 May 2016 (24.05.2016) EP (71) Applicant: NOVOZYMES A/S [DK/DK]; Krogshoejvej 36, 2880 Bagsvaerd (DK). (72) Inventors: CARSTENSEN, Lone; Krogshoejvej 36, 2880 Bagsvaerd (DK). SPODSBERG, Nikolaj; Krogshoejvej 36, 2880 Bagsvaerd (DK). GJERMANSEN, Morten; Krogshoejvej 36, 2880 Bagsvaerd (DK). SALOMON, Jes- per; Krogshoejvej 36, 2880 Bagsvaerd (DK). KROGH, Kristian, B,R,M,; Krogshoejvej 36, 2880 Bagsvaerd (DK). (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DJ, DK, DM, DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JP, KE, KG, KH, KN, KP, KR, KW, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY,TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. -

Leguminosae – Ancistrotropis (Papilionoideae) E Filogenia Do Gênero Ancistrotropis

FLORA DA BAHIA: LEGUMINOSAE – ANCISTROTROPIS (PAPILIONOIDEAE) E FILOGENIA DO GÊNERO ANCISTROTROPIS Felipe da Silva Santos¹; Luciano Paganucci de Queiroz²; Cristiane Snak³ 1. Bolsista PROBIC, Graduando em Bacharelado em Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Estadual de Feira de Santana, email: [email protected] 2. Orientador, Departamento de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Estadual de Feira de Santana, email: [email protected] 3. Coorientadora, Departamento de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Estadual de Feira de Santana, email: [email protected] PALAVRAS-CHAVE: Phaseolineae, taxonomia, Vigna s.l. INTRODUÇÃO Leguminosae compreende cerca de 19.500 espécies e 770 gêneros, dos quais 220 gêneros e cerca de 2.835 espécies ocorrem no Brasil. A Bahia, com cerca de 937 espécies, é o segundo estado com maior diversidade (BFG 2015, LPWG 2013, 2017). A família é dividida em seis subfamílias: Cercidoideae, Detarioideae, Dialioideae, Duparquetioideae, Caesalpinioideae e Papilionoideae, sendo as cinco primeiras segregadas de Caesalpinioideae s.l. e Mimosoideae incluída em Caesalpinioideae (LPWG 2017). A circunscrição de Papilionoideae não teve alterações e ela inclui 29 tribos, 503 gêneros e cerca de 14.000 espécies (LPWG 2013, 2017, Queiroz et al. 2015). Phaseoleae é a tribo mais diversa, tendo como características principais hábito volúvel e as folhas trifoliadas (Bruneau et al. 1995), e dentre suas diversas subtribos, Phaseolineae é a que possui o maior número de espécies. Phaseolineae é um grupo monofilético (Kajita et al. 2001) mas, apesar disso, possui diversos problemas de delimitação entre os gêneros e entre as espécies de diversos gêneros. Dentre esses gêneros, Phaseolus e Vigna formam um complexo que há muito tempo vem sendo estudado pela sua dificuldade de delimitação (Maréchal et al. -

Karyotype Analysis of Twelve Species Belonging to Genus Vigna

C 1999 The Japan Mendel Society Cytologia 64: 117-127, 1999 Karyotype Analysis of Twelve Species belonging to Genus Vigna Gianfranco Venoral, Sebastiano Blangifortil and Roberto Cremonini2 1 Stazione Sperimentale di Granicoltura per la Sicilia, Via Rossini 1, 95041 Caltagirone (CT), Italy 2 Dipartimento Scienze Botaniche, Via Luca Chini 5, 56126 Pisa, Italy Accepted October 26, 1998 Summary Cowpea,Vigna unguiculata (L.) Walp., is an importantcrop for manydeveloping coun- tries. Its potential cannotbe fully achieveddue to scarseresistance to pathogens.Source of resistance are present in wild gene pool, therefore, the introductionof genes for valuable traits from wild species to Vignaunguiculata faced an obstacle due to crossabilitybarriers betweenspecies. The study of the chromosomalmorphology could be usefulin a modernplant breedingapproach of cow- pea. Recentlythe use of image analysissystem to the karyotypingof plant specieswith few chromo- somes has allowed the productionof detailed karyotypesemployed for interspecificcomparisons. Twelvespecies belonging to four differentsubgenera and to six sectionsaccording to Marechalet al. (1978) were analysed by image analysissystem. The karyomorphologicalparameters were utilised for computingkaryosimmetry according to Stebbins(1971). Key words Vignaspecies, Image analysis,Karyotype, Taxonomy. The cowpea, V unguiculata (L.) Walp., is an important leguminous in many developing coun- tries where it represents the principal source of proteins. This species suffers attacks of seed para- sites, that drastically reduces the potential feed of this crop (Rachie and Rawall 1976). The aim of this research is the study of the chromosomal morphology that serves to describe the phyletic relationships (Stebbins 1971, Lackey 1980) and overcoming the hybridisation barriers for the insertion of useful genes from wild species. The chromosomes of the genus Vigna are very small (Parida et al. -

Legume Phylogeny and Classification in the 21St Century: Progress, Prospects and Lessons for Other Species-Rich Clades

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2013 Legume phylogeny and classification in the 21st century: progress, prospects and lessons for other species-rich clades Legume Phylogeny Working Group ; Bruneau, Anne ; Doyle, Jeff J ; Herendeen, Patrick ; Hughes, Colin E ; Kenicer, Greg ; Lewis, Gwilym ; Mackinder, Barbara ; Pennington, R Toby ; Sanderson, Michael J ; Wojciechowski, Martin F ; Koenen, Erik Posted at the Zurich Open Repository and Archive, University of Zurich ZORA URL: https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-78167 Journal Article Published Version Originally published at: Legume Phylogeny Working Group; Bruneau, Anne; Doyle, Jeff J; Herendeen, Patrick; Hughes, Colin E; Kenicer, Greg; Lewis, Gwilym; Mackinder, Barbara; Pennington, R Toby; Sanderson, Michael J; Wojciechowski, Martin F; Koenen, Erik (2013). Legume phylogeny and classification in the 21st century: progress, prospects and lessons for other species-rich clades. Taxon, 62(2):217-248. TAXON 62 (2) • April 2013: 217–248 LPWG • Legume phylogeny and classification REVIEWS Legume phylogeny and classification in the 21st century: Progress, prospects and lessons for other species-rich clades The Legume Phylogeny Working Group1 This paper was compiled by Anne Bruneau,2 Jeff J. Doyle,3 Patrick Herendeen,4 Colin Hughes,5 Greg Kenicer,6 Gwilym Lewis,7 Barbara Mackinder,6,7 R. Toby Pennington,6 Michael J. Sanderson8 and Martin F. Wojciechowski9 who were equally responsible and listed here in alphabetical order only, with contributions from Stephen Boatwright,10 Gillian Brown,11 Domingos Cardoso,12 Michael Crisp,13 Ashley Egan,14 Renée H. Fortunato,15 Julie Hawkins,16 Tadashi Kajita,17 Bente Klitgaard,7 Erik Koenen,5 Matt Lavin18, Melissa Luckow,3 Brigitte Marazzi,8 Michelle M. -

Gene Flow in Phaseolus Beans and Its Role As a Plausible Driver of Ecological Fitness and Expansion of Cultigens

fevo-09-618709 May 17, 2021 Time: 16:15 # 1 REVIEW published: 21 May 2021 doi: 10.3389/fevo.2021.618709 Gene Flow in Phaseolus Beans and Its Role as a Plausible Driver of Ecological Fitness and Expansion of Cultigens María Isabel Chacón-Sánchez1*, Jaime Martínez-Castillo2, Jorge Duitama3 and Daniel G. Debouck4 1 Departamento de Agronomía, Facultad de Ciencias Agrarias, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, Bogotá, Colombia, 2 Unidad de Recursos Naturales, Centro de Investigación Científica de Yucatán, Yucatán, Mexico, 3 Systems and Computing Engineering Department, Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá, Colombia, 4 Genetic Resources Program, International Center for Tropical Agriculture – CIAT, Cali, Colombia The genus Phaseolus, native to the Americas, is composed of more than eighty wild species, five of which were domesticated in pre-Columbian times. Since the beginning of domestication events in this genus, ample opportunities for gene flow with wild relatives have existed. The present work reviews the extent of gene flow in the genus Phaseolus Edited by: in primary and secondary areas of domestication with the aim of illustrating how this Giancarlo Conde Xavier Oliveira, evolutionary force may have conditioned ecological fitness and the widespread adoption University of São Paulo, Brazil of cultigens. We focus on the biological bases of gene flow in the genus Phaseolus Reviewed by: from a spatial and time perspective, the dynamics of wild-weedy-crop complexes in the Elizabeth Ann Veasey, University of São Paulo, Brazil common bean and the Lima bean, the two most important domesticated species of the Marcelo Cavallari, genus, and the usefulness of genomic tools to detect inter and intraspecific introgression Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation (EMBRAPA), Brazil events. -

Microsoft Word

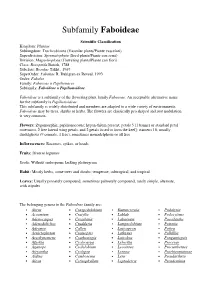

Subfamily Faboideae Scientific Classification Kingdom: Plantae Subkingdom: Tracheobionta (Vascular plants/Piante vascolari) Superdivision: Spermatophyta (Seed plants/Piante con semi) Division: Magnoliophyta (Flowering plants/Piante con fiori) Class: Rosopsida Batsch, 1788 Subclass: Rosidae Takht., 1967 SuperOrder: Fabanae R. Dahlgren ex Reveal, 1993 Order: Fabales Family: Fabaceae o Papilionacee Subfamily: Faboideae o Papilionoideae Faboideae is a subfamily of the flowering plant family Fabaceae . An acceptable alternative name for the subfamily is Papilionoideae . This subfamily is widely distributed and members are adapted to a wide variety of environments. Faboideae may be trees, shrubs or herbs. The flowers are classically pea shaped and root nodulation is very common. Flowers: Zygomorphic, papilionaceous; hypan-thium present; petals 5 [1 banner or standard petal outermost, 2 free lateral wing petals, and 2 petals fused to form the keel]; stamens 10, usually diadelphous (9 connate, 1 free), sometimes monadelphous or all free Inflorescences: Racemes, spikes, or heads Fruits: Diverse legumes Seeds: Without endosperm; lacking pleurogram Habit: Mostly herbs, some trees and shrubs; temperate, subtropical, and tropical Leaves: Usually pinnately compound, sometimes palmately compound, rarely simple, alternate, with stipules The belonging genera to the Faboideae family are: • Abrus • Craspedolobium • Kummerowia • Podalyria • Acosmium • Cratylia • Lablab • Podocytisus • Adenocarpus • Crotalaria • Laburnum • Poecilanthe • Adenodolichos • Cruddasia -

Local Biodiversity Erosion in South Brazilian Grasslands with Even Slight Landscape Habitat Loss PPG Botˆanica, 6 De Junho De 2017 Reviewers: Prof

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO SUL INSTITUTO DE BIOCIÊNCIAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM BOTÂNICA LOCAL BIODIVERSITY EROSION IN SOUTH BRAZILIAN GRASSLANDS EVEN WITH SLIGHT LANDSCAPE HABITAT LOSS IngmAr René StAude Orientador: Prof. Dr. Gerhard Ernst Overbeck Porto Alegre 2017 UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO RIO GRANDE DO SUL INSTITUTO DE BIOCIÊNCIAS PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM BOTÂNICA LOCAL BIODIVERSITY EROSION IN SOUTH BRAZILIAN GRASSLANDS EVEN WITH SLIGHT LANDSCAPE HABITAT LOSS IngmAr René StAude Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Botânica como um dos requisitos para a obtenção do grau de Mestre em Botânica pela Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul Orientador: Prof. Dr. Gerhard Ernst Overbeck Porto Alegre 2017 Ingmar R. Staude Local biodiversity erosion in South Brazilian grasslands with even slight landscape habitat loss PPG Botˆanica, 6 de Junho de 2017 Reviewers: Prof. Dr. Sandra C. M¨uller, Prof. Dr. Jo˜aoA. Jarenkow and Dr. Anaclara Guido Supervisors: Prof. Dr. Gerhard E. Overbeck Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul Laboratory of Grassland Vegetation PPG Botˆanica Av. Bento Gon¸calves, 9500 - Bloco IV - Pr´edio 43433 CEP 91501-970 Porto Alegre Conte´udo Pref´acio 1 Agradecimentos ....................................... 1 ListadeFiguras ....................................... 2 ListadeTabelas ....................................... 3 Introdu¸c˜aoGeral....................................... 4 Referˆencias .......................................... 6 Chapter 1: Local biodiversity erosion in South Brazilian -

A New Species of Ancistrotropis (Leguminosae, Papilionoideae, Phaseoleae) Endemic to Brazil

Phytotaxa 172 (3): 280–284 ISSN 1179-3155 (print edition) www.mapress.com/phytotaxa/ PHYTOTAXA Copyright © 2014 Magnolia Press Article ISSN 1179-3163 (online edition) http://dx.doi.org/10.11646/phytotaxa.172.3.9 A new species of Ancistrotropis (Leguminosae, Papilionoideae, Phaseoleae) endemic to Brazil CRISTIANE SNAK1, JOÃO LUIZ DE ARRUDA MOREIRA2 & ANA MARIA GOULART DE AZEVEDO TOZZI2 1 Programa de Pós-graduação em Botânica, Departamento de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Estadual de Feira de Santana, Av. Transnordestina s.n., Novo Horizonte, CEP 44036-900, Feira de Santana, Bahia, Brazil; e-mail: [email protected] 2 Departamento de Biologia Vegetal, Instituto de Biologia, Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Caixa Postal 6109, CEP 13083-970, Campinas, São Paulo, Brazil; e-mail: [email protected] Abstract A new species of Ancistrotropis is described and illustrated here. Ancistrotropis serrana occurs in several habitats in Brazil such as grasslands, “campo rupestre”, “restinga”, “cerrado” and gallery forest. Resumo Uma nova espécie de Ancistrotropis é aqui descrita e ilustrada. Ancistrotropis serrana ocorre em diversos habitats no Brasil, tais como, campos, campo rupestre, restinga, cerrado e mata de galeria. Key words: Fabaceae, Faboideae, taxonomy, Vigna Introduction Ancistrotropis Delgado-Salinas (2011:1704) is a neotropical genus with about six species recently segregated from Vigna Savi (1824:113) by Delgado-Salinas et al. (2011). It belongs to subtribe Phaseolinae, a taxonomically challenging group, particularly due to the Phaseolus-Vigna-Macroptilium complex. The generic limits within Phaseolinae were reviewed by Maréchal et al. (1978) and Lackey (1983). Later, Delgado-Salinas et al. (2011) elucidated the relationships amongst the genera of the subtribe using molecular data and proposed the segregation of Vigna in seven genera. -

Lianas and Climbing Plants of the Neotropics: Fabaceae

GUIDE TO THE GENERA OF LIANAS AND CLIMBING PLANTS IN THE NEOTROPICS FABACEAE By Pedro Acevedo-Rodríguez (5 Oct 2020) One of the largest plant families of the world with ca. 19,500 species exhibiting diverse habits including trees, erect or climbing shrubs, vines, lianas and terrestrial or aquatic herbs, with cosmopolitan distribution. Herbaceous vines often are twiners or scramblers or less often have tendrils (e.g., Vicia). Lianas for the most part have prehensile branches, twining stems, cirri (e.g., Machaerium, Senegalia), and less often are scramblers with armed stems or leaves. There are about 254 genera and 5360 species of Fabaceae in the Neotropics*. Of these, 57 genera contain lianas or climbing plants for a total of 840 species, occurring in a wide range of habitats, but more predominant in lowland moist forests, savannas, gallery forests, and in open disturbed biomes. Neotropical climbing Fabaceae are most diverse below 1500 m of elevation. (* total numbers are from G. Lewis, pers. comm., 2018). Sigmoidotropis speciosa (Kunth) A.Delgado, photo by P. Acevedo Diagnostics: Being a morphologically diverse family it is sometimes difficult to distinguish its members from vines in other families. As a general rule, leaves in the Fabaceae are alternate, compound and stipulate. Many herbaceous vines are twiners and have trifoliolate leaves; scrambling shrubs are often armed with recurved prickles and have bipinnate leaves; some lianas have flattened stems, usually with successive cambia, and bright red exudates. 1 General Characters 1. STEMS. Stems are woody or less often herbaceous. Woody, mature stems are usually 1 to 5 cm in diameter, although in several genera (e.g., Dalbergia, Machaerium and Schnella) they may reach 30 cm or more in diameter, and more than 30 m in length.