Bumblebees of Devon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poland 12 – 20 May 2018

Poland 12 – 20 May 2018 Holiday participants Gerald and Janet Turner Brian Austin and Mary Laurie-Pile Mike and Val Grogutt Mel and Ann Leggett Ann Greenizan Rina Picciotto Leaders Artur Wiatr www.biebrza-explorer.pl and Tim Strudwick. Report, lists and photos by Tim Strudwick. In Biebrza National Park we stayed at Dwor Dobarz http://dwordobarz.pl/ In Białowieża we stayed at Gawra Pensjon at www.gawra.Białowieża.com Cover photos: sunset over Lawaki fen; fallen deadwood in Białowieża strict reserve. Below: group photo taken at Dwor Dobarz and Biebrza lower basin from Burzyn. This holiday, as for every Honeyguide holiday, also puts something into conservation in our host country by way of a contribution to the wildlife that we enjoyed. The conservation contribution this year of £40 per person was supplemented by gift aid through the Honeyguide Wildlife Charitable Trust, leading to a donation of £490. The donation went to The Workshop of Living Architecture, a small NGO that runs environmental projects in and near Biebrza Marshes. This includes building new nesting platforms for white storks, often in response to storm damage or roof renovation, or simply to replace old nests. The total for all conservation contributions through Honeyguide since 1991 was £124,860 to August 2018. 2 DAILY DIARY Saturday 12 May – Warsaw to Biebrza Following an early flight from Luton, the group arrived at Warsaw airport and soon found local leader Artur and driver Rafael in the arrival hall. After introductions, including the customary carnations for the ladies, and the briefest of delays to resolve a suitcase mix up, we quickly boarded the waiting bus. -

THE HUMBLE-BEE MACMILLAN and CO., Limited LONDON BOMBAY CALCUTTA MELBOURNE the MACMILLAN COMPANY NEW YORK BOSTON CHICAGO DALLAS SAN FRANCISCO the MACMILLAN CO

THE HUMBLE-BEE MACMILLAN AND CO., Limited LONDON BOMBAY CALCUTTA MELBOURNE THE MACMILLAN COMPANY NEW YORK BOSTON CHICAGO DALLAS SAN FRANCISCO THE MACMILLAN CO. OF CANADA, Ltd. TORONTO A PET QUEEN OF BOMBUS TERRESTRIS INCUBATING HER BROOD. (See page 139.) THE HUMBLE-BEE ITS LIFE-HISTORY AND HOW TO DOMESTICATE IT WITH DESCRIPTIONS OF ALL THE BRITISH SPECIES OF BOMBUS AND PSITHTRUS BY \ ; Ff W. U SLADEN FELLOW OF THE ENTOMOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF LONDON AUTHOR OF 'QUEEN-REARING IN ENGLAND ' ILLUSTRATED WITH PHOTOGRAPHS AND DRAWINGS BY THE AUTHOR AND FIVE COLOURED PLATES PHOTOGRAPHED DIRECT FROM NA TURE MACMILLAN AND CO., LIMITED ST. MARTIN'S STREET, LONDON 1912 COPYRIGHT Printed in ENGLAND. PREFACE The title, scheme, and some of the contents of this book are borrowed from a little treatise printed on a stencil copying apparatus in August 1892. The boyish effort brought me several naturalist friends who encouraged me to pursue further the study of these intelligent and useful insects. ..Of these friends, I feel especially indebted to the late Edward Saunders, F.R.S., author of The Hymen- optera Aculeata of the British Islands, and to the late Mrs. Brightwen, the gentle writer of Wild Nattcre Won by Kindness, and other charming studies of pet animals. The general outline of the life-history of the humble-bee is, of course, well known, but few observers have taken the trouble to investigate the details. Even Hoffer's extensive monograph, Die Htimmeln Steiermarks, published in 1882 and 1883, makes no mention of many remarkable can particulars that I have witnessed, and there be no doubt that further investigations will reveal more. -

Species Knowledge Review: Shrill Carder Bee Bombus Sylvarum in England and Wales

Species Knowledge Review: Shrill carder bee Bombus sylvarum in England and Wales Editors: Sam Page, Richard Comont, Sinead Lynch, and Vicky Wilkins. Bombus sylvarum, Nashenden Down nature reserve, Rochester (Kent Wildlife Trust) (Photo credit: Dave Watson) Executive summary This report aims to pull together current knowledge of the Shrill carder bee Bombus sylvarum in the UK. It is a working document, with a view to this information being reviewed and added when needed (current version updated Oct 2019). Special thanks to the group of experts who have reviewed and commented on earlier versions of this report. Much of the current knowledge on Bombus sylvarum builds on extensive work carried out by the Bumblebee Working Group and Hymettus in the 1990s and early 2000s. Since then, there have been a few key studies such as genetic research by Ellis et al (2006), Stuart Connop’s PhD thesis (2007), and a series of CCW surveys and reports carried out across the Welsh populations between 2000 and 2013. Distribution and abundance Records indicate that the Shrill carder bee Bombus sylvarum was historically widespread across southern England and Welsh lowland and coastal regions, with more localised records in central and northern England. The second half of the 20th Century saw a major range retraction for the species, with a mixed picture post-2000. Metapopulations of B. sylvarum are now limited to five key areas across the UK: In England these are the Thames Estuary and Somerset; in South Wales these are the Gwent Levels, Kenfig–Port Talbot, and south Pembrokeshire. The Thames Estuary and Gwent Levels populations appear to be the largest and most abundant, whereas the Somerset population exists at a very low population density, the Kenfig population is small and restricted. -

Beewalk Report 2020

BeeWalk Annual Report 2020 Richard Comont and Helen Dickinson BeeWalk Annual Report 2020 About BeeWalk BeeWalk is a standardised bumblebee-monitoring scheme active across Great Britain since 2008, and this report covers the period 2008–19. The scheme protocol involves volunteer BeeWalkers walking the same fixed route (a transect) at least once a month between March and October (inclusive). This covers the full flight period of the bumblebees, including emergence from overwintering and workers tailing off. Volunteers record the abundance of each bumblebee species seen in a 4 m x 4 m x 2 m ‘recording box’ in order to standardise between habitats and observers. It is run by Dr Richard Comont and Helen Dickinson of the Bumblebee Conservation Trust (BBCT). To contact the scheme organisers, please email [email protected]. Acknowledgements We are indebted to the volunteers and organisations past and present who have contributed data to the scheme or have helped recruit or train others in connection with it. Thanks must also go to all the individuals and organisations who allow or even actively promote access to their land for bumblebee recording. We would like to thank the financial contribution by the Redwing Trust, Esmée Fairbairn Foundation, Garfield Weston Foundation and the many other organisations, charitable trusts and individuals who have supported the BeeWalk scheme in particular, and the Bumblebee Conservation Trust in general. In particular, the Biological Records Centre have provided website support, data storage and desk space free of charge. Finally, we would like to thank the photographers who have allowed their excellent images to be used as part of this BeeWalk Annual Report. -

Bumblebee in the UK

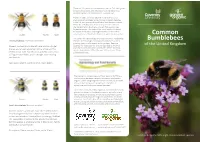

There are 24 species of bumblebee in the UK. This field guide contains illustrations and descriptions of the eight most common species. All illustrations 1.5x actual size. There has been a marked decline in the diversity and abundance of wild bees across Europe in recent decades. In the UK, two species of bumblebee have become extinct within the last 80 years, and seven species are listed in the Government’s Biodiversity Action Plan as priorities for conservation. This decline has been largely attributed to habitat destruction and fragmentation, as a result of Queen Worker Male urbanisation and the intensification of agricultural practices. Common The Centre for Agroecology and Food Security is conducting Tree bumblebee (Bombus hypnorum) research to encourage and support bumblebees in food Bumblebees growing areas on allotments and in gardens. Bees are of the United Kingdom Queens, workers and males all have a brown-ginger essential for food security, and are regarded as the most thorax, and a black abdomen with a white tail. This important insect pollinators worldwide. Of the 100 crop species that provide 90% of the world’s food, over 70 are recent arrival from France is now present across most pollinated by bees. of England and Wales, and is thought to be moving northwards. Size: queen 18mm, worker 14mm, male 16mm The Centre for Agroecology and Food Security (CAFS) is a joint initiative between Coventry University and Garden Organic, which brings together social and natural scientists whose collective research expertise in the fields of agriculture and food spans several decades. The Centre conducts critical, rigorous and relevant research which contributes to the development of agricultural and food production practices which are economically sound, socially just and promote long-term protection of natural Queen Worker Male resources. -

Global Trends in Bumble Bee Health

EN65CH11_Cameron ARjats.cls December 18, 2019 20:52 Annual Review of Entomology Global Trends in Bumble Bee Health Sydney A. Cameron1,∗ and Ben M. Sadd2 1Department of Entomology, University of Illinois, Urbana, Illinois 61801, USA; email: [email protected] 2School of Biological Sciences, Illinois State University, Normal, Illinois 61790, USA; email: [email protected] Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2020. 65:209–32 Keywords First published as a Review in Advance on Bombus, pollinator, status, decline, conservation, neonicotinoids, pathogens October 14, 2019 The Annual Review of Entomology is online at Abstract ento.annualreviews.org Bumble bees (Bombus) are unusually important pollinators, with approx- https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ento-011118- imately 260 wild species native to all biogeographic regions except sub- 111847 Saharan Africa, Australia, and New Zealand. As they are vitally important in Copyright © 2020 by Annual Reviews. natural ecosystems and to agricultural food production globally, the increase Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2020.65:209-232. Downloaded from www.annualreviews.org All rights reserved in reports of declining distribution and abundance over the past decade ∗ Corresponding author has led to an explosion of interest in bumble bee population decline. We Access provided by University of Illinois - Urbana Champaign on 02/11/20. For personal use only. summarize data on the threat status of wild bumble bee species across bio- geographic regions, underscoring regions lacking assessment data. Focusing on data-rich studies, we also synthesize recent research on potential causes of population declines. There is evidence that habitat loss, changing climate, pathogen transmission, invasion of nonnative species, and pesticides, oper- ating individually and in combination, negatively impact bumble bee health, and that effects may depend on species and locality. -

Bombus Terrestris) Colonies

veterinary sciences Article Replicative Deformed Wing Virus Found in the Head of Adults from Symptomatic Commercial Bumblebee (Bombus terrestris) Colonies Giovanni Cilia , Laura Zavatta, Rosa Ranalli, Antonio Nanetti * and Laura Bortolotti CREA Research Centre for Agriculture and Environment, Via di Saliceto 80, 40128 Bologna, Italy; [email protected] (G.C.); [email protected] (L.Z.); [email protected] (R.R.); [email protected] (L.B.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The deformed wing virus (DWV) is one of the most common honey bee pathogens. The virus may also be detected in other insect species, including Bombus terrestris adults from wild and managed colonies. In this study, individuals of all stages, castes, and sexes were sampled from three commercial colonies exhibiting the presence of deformed workers and analysed for the presence of DWV. Adults (deformed individuals, gynes, workers, males) had their head exscinded from the rest of the body and the two parts were analysed separately by RT-PCR. Juvenile stages (pupae, larvae, and eggs) were analysed undissected. All individuals tested positive for replicative DWV, but deformed adults showed a higher number of copies compared to asymptomatic individuals. Moreover, they showed viral infection in their heads. Sequence analysis indicated that the obtained DWV amplicons belonged to a strain isolated in the United Kingdom. Further studies are needed to Citation: Cilia, G.; Zavatta, L.; characterize the specific DWV target organs in the bumblebees. The result of this study indicates the Ranalli, R.; Nanetti, A.; Bortolotti, L. evidence of DWV infection in B. -

Vertical Stratification of Plant-Pollinator Interactions in A

A peer-reviewed version of this preprint was published in PeerJ on 22 June 2018. View the peer-reviewed version (peerj.com/articles/4998), which is the preferred citable publication unless you specifically need to cite this preprint. Klecka J, Hadrava J, Koloušková P. 2018. Vertical stratification of plant–pollinator interactions in a temperate grassland. PeerJ 6:e4998 https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.4998 1 Vertical stratification of plant-pollinator 2 interactions in a temperate grassland 1 1,2 1 3 Jan Klecka , Jir´ıHadravaˇ , and Pavla Kolouskovˇ a´ 1 4 Czech Academy of Sciences, Biology Centre, Institute of Entomology, Ceskˇ e´ 5 Budejovice,ˇ Czech Republic 2 6 Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, Charles University, Prague, Czech 7 Republic 8 Corresponding author: 9 Jan Klecka 10 Email address: [email protected] 11 ABSTRACT 12 Visitation of plants by different pollinators depends on individual plant traits, spatial context, and other 13 factors. A neglected aspect of small-scale variation of plant-pollinator interactions is the role of vertical 14 position of flowers. We conducted a series of experiments to study vertical stratification of plant-pollinator 15 interactions in a dry grassland. We observed flower visitors on cut inflorescences of Centaurea scabiosa 16 and Inula salicina placed at different heights above ground in two types of surrounding vegetation: short 17 and tall. Even at such a small-scale, we detected significant shift in total visitation rate of inflorescences 18 in response to their vertical position. In short vegetation, inflorescences close to the ground were visited 19 more frequently, while in tall vegetation, inflorescences placed higher received more visits. -

Hoverflies: the Garden Mimics

Article Hoverflies: the garden mimics. Edmunds, Malcolm Available at http://clok.uclan.ac.uk/1620/ Edmunds, Malcolm (2008) Hoverflies: the garden mimics. Biologist, 55 (4). pp. 202-207. ISSN 0006-3347 It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. For more information about UCLan’s research in this area go to http://www.uclan.ac.uk/researchgroups/ and search for <name of research Group>. For information about Research generally at UCLan please go to http://www.uclan.ac.uk/research/ All outputs in CLoK are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including Copyright law. Copyright, IPR and Moral Rights for the works on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the policies page. CLoK Central Lancashire online Knowledge www.clok.uclan.ac.uk Hoverflies: the garden mimics Mimicry offers protection from predators by convincing them that their target is not a juicy morsel after all. it happens in our backgardens too and the hoverfly is an expert at it. Malcolm overflies are probably the best the mimic for the model and do not attack Edmunds known members of tbe insect or- it (Edmunds, 1974). Mimicry is far more Hder Diptera after houseflies, blue widespread in the tropics than in temperate bottles and mosquitoes, but unlike these lands, but we have some of the most superb insects they are almost universally liked examples of mimicry in Britain, among the by the general public. They are popular hoverflies. -

Bumblebee Species Differ in Their Choice of Flower Colour Morphs of Corydalis Cava (Fumariaceae)?

Do queens of bumblebee species differ in their choice of flower colour morphs of Corydalis cava (Fumariaceae)? Myczko, Ł., Banaszak-Cibicka, W., Sparks, T.H Open access article deposited by Coventry University’s Repository Original citation & hyperlink: Myczko, Ł, Banaszak-Cibicka, W, Sparks, TH & Tryjanowski, P 2015, 'Do queens of bumblebee species differ in their choice of flower colour morphs of Corydalis cava (Fumariaceae)?' Apidologie, vol 46, no. 3, pp. 337-345. DOI 10.1007/s13592-014-0326-x ISSN 0044-8435 ESSN 1297-9678 Publisher: Springer Verlag The final publication is available at Springer via https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13592-014- 0326-x This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited. Copyright 2014© and Moral Rights are retained by the author(s) and/ or other copyright owners. Apidologie (2015) 46:337–345 Original article * INRA, DIB and Springer-Verlag France, 2014. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com DOI: 10.1007/s13592-014-0326-x Do queens of bumblebee species differ in their choice of flower colour morphs of Corydalis cava (Fumariaceae)? Łukasz MYCZKO, Weronika BANASZAK-CIBICKA, Tim H. SPARKS, Piotr TRYJANOWSKI Institute of Zoology, Poznań University of Life Sciences, Wojska Polskiego 71C, 60-625, Poznań, Poland Received 6 June 2014 – Revised 18 September 2014 – Accepted 6 October 2014 Abstract – Bumblebee queens require a continuous supply of flowering food plants from early spring for the successful development of annual colonies. -

Hymenoptera: Aculeata Part 1 – Bees

SCOTTISH INVERTEBRATE SPECIES KNOWLEDGE DOSSIER Hymenoptera: Aculeata Part 1 – Bees A. NUMBER OF SPECIES IN UK: 318 B. NUMBER OF SPECIES IN SCOTLAND: 110 (4 thought to be extinct, 2 may be found – insufficient data) C. EXPERT CONTACTS Please contact [email protected] for details. D. SPECIES OF CONSERVATION CONCERN Listed species UK Biodiversity Action Plan Species known to occur in Scotland (the current list was published in August 2007): Andrena tarsata Tormentil mining bee Bombus distinguendus Great yellow bumblebee Bombus muscorum Moss (Large) carder bumblebee Bombus ruderarius Red-shanked (Red-tailed) carder bumblebee Colletes floralis Northern colletes Osmia inermis a mason bee Osmia parietina a mason bee Osmia uncinata a mason bee Bombus distinguendus is also listed under the Species Action Framework of Scottish Natural Heritage, launched in 2007 (Category 1: Species for Conservation Action). 1 Other species The Scottish Biodiversity List was published in 2005 and lists the additional species (arranged below by sub-family): Andreninae Andrena cineraria Andrena helvola Andrena marginata Andrena nitida 1 Andrena ruficrus Anthophorinae Anthidium maniculatum Anthophora furcata Epeolus variegatus Nomada fabriciana Nomada leucophthalma Nomada obtusifrons Nomada robertjeotiana Sphecodes gibbus Apinae Bombus monticola Colletinae Colletes daviesanus Colletes fodiens Hylaeus brevicornis Halictinae Lasioglossum fulvicorne Lasioglossum smeathmanellum Lasioglossum villosulum Megachillinae Osmia aurulenta Osmia caruelescens Osmia rufa Stelis -

BELARUS Forest Birds of Deepest Belarus 1 – 8 May 2016

BELARUS Forest Birds of Deepest Belarus 1 – 8 May 2016 TOUR REPORT Leaders: Barrie Cooper & Attila Steiner Azure tit © Barrie Cooper Highlights Several prolonged and excellent views of azure tits Good views of aquatic warbler, red-breasted and collared flycatchers Nine species of woodpecker Good views of great snipe lekking, plus citrine wagtail and penduline tit Great grey owl, pygmy owl, long-eared owl 14 species of raptor Waders seen in the hand included marsh sandpiper, male and female ruff Sunday 1 May The group arrived in good time at Gatwick before departure for our direct flight to Minsk. On arrival, we were met by Attila, Katia (our local assistant and translator) and Richie the driver, plus group members David and Jill who had spent the previous two days in Minsk. After a meal in the airport restaurant we set off for the four-hour journey to Turov and arrived at just before one o’clock local time. Monday 2 May Mainly cloudy, 15 degrees Alshany, Ledzets & Turov Meadows After a later than normal breakfast, we gathered outside the hotel to see the two white stork nests in the town square and the statue of Terek sandpiper. Marsh terns were flying around over the river and a few waders were on the meadows, but more of that later. A brief stop on the edge of Turov provided us with good views of garganey, ruff, Montagu’s and marsh harriers. A pair of common cranes, whinchat and yellow wagtail added to the variety. Our first destination was the river at Alshany.