Interglacial

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NM News Aug 15

THE NEEDHAM MARKET NEWSLETTER PUBLISHED BY NEEDHAM MARKET TOWN COUNCIL August 2015 - No 470 and Distributed Throughout Needham Market Free of Charge Needham Market Phoenix Youth Football Club 40th Year Celebrations 1977 See details on page 22 2014 www.needhammarkettc.co.uk TOWN COUNCIL Needham Market Town Council OFFICE TOWN CLERK: ASSISTANT TOWN CLERK: Town Council Office, Kevin Hunter Kelaine Spurdens Community Centre, School Street, LIST OF TOWN COUNCILLORS: TELEPHONE: Needham Market IP6 8BB BE ANNIS OBE Grinstead House, Grinstead Hill, NM IP6 8EY 01449 720531 (07927 007895) Telephone: 01449 722246. D CAMPBELL ‘Chain House’ 1 High Street, NM, IP6 8AL 01449 720952 An answerphone is in R CAMPBELL The Acorns, Hill House Lane, NM, IP6 8EA 01449 720729 operation when the office TS CARTER Danescroft, Ipswich Road, NM, IP6 8EG 01449 401325 is unmanned. RP DARNELL 27 Pinecroft Way, NM, IP6 8HB 07990 583162 The office is open to the JE LEA MA Town Mayor/Chair of Council public Mondays and 109 Jubilee Crescent, NM IP6 8AT 01449 721544 Thursdays 10am to 12noon. I MASON 114 Quinton Road, NM IP6 8TH 01449 721162 MG NORRIS 20 Stowmarket Road, NM, IP6 8DS 01449 720871 E.mail: KMN OAKES, 89 Stowmarket Road, NM, IP6 8ED 07702 339971 clerk@needhammarkettc. f9.co.uk S PHILLIPS 46 Crowley Road IP6 8BJ 01449 721710 S ROWLAND 9 Orchid Way, NM, IP6 8JQ 01449 721507 Web: D SPURLING 36 Drift Court, NM, IP6 8SZ 01449 723208 www.needhammarkettc. co.uk M SPURLING 36 Drift Court, NM, IP6 8SZ 01449 723208 X STANSFIELD Deputy Town Mayor/Deputy Chair of Council Town Council meetings Hope Cottage, 7 Stowmarket Road IP6 8DR 07538 058304 are held on the first and third Wednesdays of each AL WARD MBE 22 Chalkeith Road, NM, IP6 8HA 01449 720422 month at 7:25 p.m. -

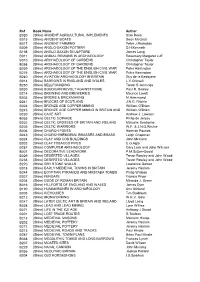

2013 CAG Library Index

Ref Book Name Author B020 (Shire) ANCIENT AGRICULTURAL IMPLEMENTS Sian Rees B015 (Shire) ANCIENT BOATS Sean McGrail B017 (Shire) ANCIENT FARMING Peter J.Reynolds B009 (Shire) ANGLO-SAXON POTTERY D.H.Kenneth B198 (Shire) ANGLO-SAXON SCULPTURE James Lang B011 (Shire) ANIMAL REMAINS IN ARCHAEOLOGY Rosemary Margaret Luff B010 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF GARDENS Christopher Taylor B268 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF GARDENS Christopher Taylor B039 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE ENGLISH CIVIL WAR Peter Harrington B276 (Shire) ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE ENGLISH CIVIL WAR Peter Harrington B240 (Shire) AVIATION ARCHAEOLOGY IN BRITAIN Guy de la Bedoyere B014 (Shire) BARROWS IN ENGLAND AND WALES L.V.Grinsell B250 (Shire) BELLFOUNDING Trevor S Jennings B030 (Shire) BOUDICAN REVOLT AGAINST ROME Paul R. Sealey B214 (Shire) BREWING AND BREWERIES Maurice Lovett B003 (Shire) BRICKS & BRICKMAKING M.Hammond B241 (Shire) BROCHS OF SCOTLAND J.N.G. Ritchie B026 (Shire) BRONZE AGE COPPER MINING William O'Brian B245 (Shire) BRONZE AGE COPPER MINING IN BRITAIN AND William O'Brien B230 (Shire) CAVE ART Andrew J. Lawson B035 (Shire) CELTIC COINAGE Philip de Jersey B032 (Shire) CELTIC CROSSES OF BRITAIN AND IRELAND Malcolm Seaborne B205 (Shire) CELTIC WARRIORS W.F. & J.N.G.Ritchie B006 (Shire) CHURCH FONTS Norman Pounds B243 (Shire) CHURCH MEMORIAL BRASSES AND BRASS Leigh Chapman B024 (Shire) CLAY AND COB BUILDINGS John McCann B002 (Shire) CLAY TOBACCO PIPES E.G.Agto B257 (Shire) COMPUTER ARCHAEOLOGY Gary Lock and John Wilcock B007 (Shire) DECORATIVE LEADWORK P.M.Sutton-Goold B029 (Shire) DESERTED VILLAGES Trevor Rowley and John Wood B238 (Shire) DESERTED VILLAGES Trevor Rowley and John Wood B270 (Shire) DRY STONE WALLS Lawrence Garner B018 (Shire) EARLY MEDIEVAL TOWNS IN BRITAIN Jeremy Haslam B244 (Shire) EGYPTIAN PYRAMIDS AND MASTABA TOMBS Philip Watson B027 (Shire) FENGATE Francis Pryor B204 (Shire) GODS OF ROMAN BRITAIN Miranda J. -

A CRITICAL EVALUATION of the LOWER-MIDDLE PALAEOLITHIC ARCHAEOLOGICAL RECORD of the CHALK UPLANDS of NORTHWEST EUROPE Lesley

A CRITICAL EVALUATION OF THE LOWER-MIDDLE PALAEOLITHIC ARCHAEOLOGICAL RECORD OF THE CHALK UPLANDS OF NORTHWEST EUROPE The Chilterns, Pegsdon, Bedfordshire (photograph L. Blundell) Lesley Blundell UCL Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD September 2019 2 I, Lesley Blundell, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Signed: 3 4 Abstract Our understanding of early human behaviour has always been and continues to be predicated on an archaeological record unevenly distributed in space and time. More than 80% of British Lower-Middle Palaeolithic findspots were discovered during the late 19th/early 20th centuries, the majority from lowland fluvial contexts. Within the British planning process and some academic research, the resultant findspot distributions are taken at face value, with insufficient consideration of possible bias resulting from variables operating on their creation. This leads to areas of landscape outside the river valleys being considered to have only limited archaeological potential. This thesis was conceived as an attempt to analyse the findspot data of the Lower-Middle Palaeolithic record of the Chalk uplands of southeast Britain and northern France within a framework complex enough to allow bias in the formation of findspot distribution patterns and artefact preservation/discovery opportunities to be identified and scrutinised more closely. Taking a dynamic, landscape = record approach, this research explores the potential influence of geomorphology, 19th/early 20th century industrialisation and antiquarian collecting on the creation of the Lower- Middle Palaeolithic record through the opportunities created for artefact preservation and release. -

Childcare Sufficiency Assessment (CSA) December 2019 – December 2020

Childcare Sufficiency Assessment (CSA) December 2019 – December 2020 Suffolk County Council Early Years and Childcare Service December 2019 Page 2 of 89 CONTENTS Table of Contents COVID – 19 5 1. Overall assessment and summary 5 England picture compared to Suffolk 6 Suffolk contextual information 6 Overall sufficiency in Suffolk 7 Deprivation 7 How Suffolk ranks across the different deprivation indices 8 2. Demand for childcare 14 Population of early years children 14 Population of school age children 14 3. Parent and carer consultation on childcare 15 4. Provision for children with special educational needs and disabilities 18 Number of children with special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) 18 5. Supply of childcare, Suffolk picture 20 Number of Early Years Providers 20 All Providers in Suffolk - LOP and Non LOP 20 Number of school age providers and places 21 6. Funded early education 22 Introduction to funded early education 22 Proportion of two year old children entitled to funded early education 22 Take up of funded early education 22 Comparison of take up of funded early education 2016 -2019 23 7. Three and four-year-old funded entitlement – 30hrs 24 30 hr codes used in Suffolk 25 Table 8 25 8. Providers offering funded early education places and places available. 26 Funded early education places available 26 Early education places at cluster level 28 9. Hourly rates 31 Hourly rate paid by Suffolk County Council 31 Hourly rate charged by providers 31 Mean hourly fee band for Suffolk 31 December 2019 Page 3 of 89 10. Quality of childcare 32 Ofsted inspection grades 32 11. -

Babergh District Council Work Completed Since April

WORK COMPLETED SINCE APRIL 2015 BABERGH DISTRICT COUNCIL Exchange Area Locality Served Total Postcodes Fibre Origin Suffolk Electoral SCC Councillor MP Premises Served Division Bildeston Chelsworth Rd Area, Bildeston 336 IP7 7 Ipswich Cosford Jenny Antill James Cartlidge Boxford Serving "Exchange Only Lines" 185 CO10 5 Sudbury Stour Valley James Finch James Cartlidge Bures Church Area, Bures 349 CO8 5 Sudbury Stour Valley James Finch James Cartlidge Clare Stoke Road Area 202 CO10 8 Haverhill Clare Mary Evans James Cartlidge Glemsford Cavendish 300 CO10 8 Sudbury Clare Mary Evans James Cartlidge Hadleigh Serving "Exchange Only Lines" 255 IP7 5 Ipswich Hadleigh Brian Riley James Cartlidge Hadleigh Brett Mill Area, Hadleigh 195 IP7 5 Ipswich Samford Gordon Jones James Cartlidge Hartest Lawshall 291 IP29 4 Bury St Edmunds Melford Richard Kemp James Cartlidge Hartest Hartest 148 IP29 4 Bury St Edmunds Melford Richard Kemp James Cartlidge Hintlesham Serving "Exchange Only Lines" 136 IP8 3 Ipswich Belstead Brook David Busby James Cartlidge Nayland High Road Area, Nayland 228 CO6 4 Colchester Stour Valley James Finch James Cartlidge Nayland Maple Way Area, Nayland 151 CO6 4 Colchester Stour Valley James Finch James Cartlidge Nayland Church St Area, Nayland Road 408 CO6 4 Colchester Stour Valley James Finch James Cartlidge Nayland Bear St Area, Nayland 201 CO6 4 Colchester Stour Valley James Finch James Cartlidge Nayland Serving "Exchange Only Lines" 271 CO6 4 Colchester Stour Valley James Finch James Cartlidge Shotley Shotley Gate 201 IP9 1 Ipswich -

Non-Biface Assemblages in Middle Pleistocene Western Europe. A

University of Southampton Research Repository ePrints Soton Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given e.g. AUTHOR (year of submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination http://eprints.soton.ac.uk UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON FACULTY OF LAW, ART and SOCIAL SCIENCES SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES Non-Biface Assemblages in Middle Pleistocene Western Europe. A comparative study. by Hannah Louise Fluck Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2011 1 2 Abstract This thesis presents the results of an investigation into the Clactonian assemblages of Middle Pleistocene souther Britain. By exploring other non-biface assemblages (NBAs) reported from elsewhere in Europe it seeks to illuminate our understanding of the British assemblages by viewing them in a wider context. It sets out how the historical and geopolitical context of Palaeolithic research has influenced what is investigated and how, as well as interpretations of assemblages without handaxes. A comparative study of the assemblages themselves based upon primary data gathered specifically for that purpose concludes that while there are a number of non-biface assemblages elsewhere in Europe the Clactonian assemblages do appear to be a phenomenon unique to the Thames Valley in early MIS 11. -

A Contextual Approach to the Study of Faunal Assemblages from Lower and Middle Palaeolithic Sites in the UK

A contextual approach to the study of faunal assemblages from Lower and Middle Palaeolithic sites in the UK Geoff M Smith PhD thesis submitted to University College London 2010 1 I, Geoff M Smith confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. _________________________________________________ Geoff M Smith 2 Abstract This thesis represents a site-specific, holistic analysis of faunal assemblage formation at four key Palaeolithic sites (Boxgrove, Swanscombe, Hoxne and Lynford). Principally this research tests the a priori assumption that lithic tools and modified large to medium-sized fauna recovered from Pleistocene deposits represent a cultural accumulation and direct evidence of past hominin meat-procurement behaviour. Frequently, the association of lithics and modified fauna at a site has been used to support either active large-mammal hunting by hominins or a scavenging strategy. Hominin bone surface modification (cut marks, deliberate fracturing) highlight an input at the site but cannot be used in isolation from all other taphonomic modifiers as evidence for cultural accumulation. To understand the role of hominins in faunal assemblage accumulation all other taphonomic factors at a site must first be considered. A site-specific framework was established by using data on the depositional environment and palaeoecology. This provided a context for the primary zooarchaeological data (faunal material: all elements and bone surface modification) and helped explain the impact and importance of faunal accumulators and modifiers identified during analysis. This data was synthesized with information on predator and prey behavioural ecology to assess potential conflict and competition within the site palaeoenvironment. -

MID SUFFOLK DISTRICT COUNCIL PARISH COUNCIL ELECTION Date : 3Rd May 2007

MID SUFFOLK DISTRICT COUNCIL PARISH COUNCIL ELECTION Date : 3rd May 2007 Parish Candidates Description Votes Cast Ashbocking Andrew Michael Gaught Farmer Elected Uncontested Tony Richard Gilbert Elected Robert Leggett Elected John Gordon Sinclair Pollard Engineer Elected Brian Colin Poole Elected Elizabeth Mary Stegman Elected Grahame Retired Lecturer Elected Tanner Ashfield Cum Thorpe Simon Geoffrey Edward Elected Garrett Uncontested Robert William Grimsey Elected Myles Gordon Elected Hansen Geoffrey Alan Hazlewood Elected Brian William Lennon Elected Bacton Robert James Black Elected Uncontested Bernard Gant Elected John Creasy Gooderham Elected Mary Esther Hawkins Elected Paul Dean Howlett Elected Roderick Paul Elected Wickenden Paul Elected Wigglesworth Badwell Ash Clive Frederick Bassett Elected Uncontested Angela Mary Brooks Elected Arthur George Diaper Elected Penny Frances Kirkby Elected Richard Pratt Elected David Smith Builder Elected Page 1 of 28 MID SUFFOLK DISTRICT COUNCIL PARISH COUNCIL ELECTION Date : 3rd May 2007 Parish Candidates Description Votes Cast Barham Neil Rayner Frederick Elected Cooper Uncontested Trevor David Girling Elected Jeremy Lea Elected Dorothy Lillian Blanche Mayhew Elected Gordon John Musson Elected Jan Elected Risebrow Helen Elizabeth Elected Whitefield Barking Steven Mark Independent Elected Austin Uncontested Michael Bailey Retired Local Government Officer Elected John Russell Tennant Berry Elected Alison Jane Emsden Elected Alan Kevin Jones Independent Elected Susan Margaret Elected Marsh Mike -

ELECTORAL DIVISION PROFILE 2017 This Division Comprises Eye, Fressingfield, Hoxne, Stradbroke and Laxfield Wards

HOXNE & EYE ELECTORAL DIVISION PROFILE 2017 This Division comprises Eye, Fressingfield, Hoxne, Stradbroke and Laxfield wards www.suffolkobservatory.info © Crown copyright and database rights 2017 Ordnance Survey 100023395 2 CONTENTS . Demographic Profile: Age & Ethnicity . Economy and Labour Market . Schools & NEET . Index of Multiple Deprivation . Health . Crime & Community Safety . Additional Information . Data Sources 3 ELECTORAL DIVISION PROFILES: AN INTRODUCTION These profiles have been produced to support elected members, constituents and other interested parties in understanding the demographic, economic, social and educational profile of their neighbourhoods. We have used the latest data available at the time of publication. Much more data is available from national and local sources than is captured here, but it is hoped that the profile will be a useful starting point for discussion, where local knowledge and experience can be used to flesh out and illuminate the information presented here. The profile can be used to help look at some fundamental questions e.g. Does the age profile of the population match or differ from the national profile? . Is there evidence of the ageing profile of the county in all the wards in the Division or just some? . How diverse is the community in terms of ethnicity? . What is the impact of deprivation on families and residents? . Does there seem to be a link between deprivation and school performance? . What is the breakdown of employment sectors in the area? . Is it a relatively healthy area compared to the rest of the district or county? . What sort of crime is prevalent in the community? A vast amount of additional data is available on the Suffolk Observatory www.suffolkobservatory.info The Suffolk Observatory is a free online resource that contains all Suffolk’s vital statistics; it is the one‐stop‐shop for information and intelligence about Suffolk. -

New Evidence for Complex Climate Change in MIS 11 from Hoxne, Suffolk, UK

ARTICLE IN PRESS Quaternary Science Reviews 27 (2008) 652–668 New evidence for complex climate change in MIS 11 from Hoxne, Suffolk, UK Nick Ashtona,Ã, Simon G. Lewisb, Simon A. Parfittc,d, Kirsty E.H. Penkmane, G. Russell Coopef aDepartment of Prehistory and Europe, British Museum, Franks House, 56 Orsman Road, London N1 5QJ, UK bDepartment of Geography, Queen Mary, University of London, Mile End Road, London E1 4NS, UK cDepartment of Palaeontology, Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London SW7 5BD, UK dInstitute of Archaeology, University College London, 31-34 Gordon Square, London WC1H 0PY, UK eBioArCh, Departments of Biology, Archaeology and Chemistry, University of York, Heslington, York YO10 5DD, UK fTigh-na-Cleirich, Foss, nr Pitlochry, Perthshire PH16 5NQ, UK Received 14 June 2007; received in revised form 2 January 2008; accepted 4 January 2008 Abstract The climatic signal of Marine Isotope Stage (MIS) 11 is well-documented in marine and ice-sheet isotopic records and is known to comprise at least two major warm episodes with an intervening cool phase. Terrestrial records of MIS 11, though of high resolution, are often fragmentary and their chronology is poorly constrained. However, some notable exceptions include sequences from the maar lakes in France and Tenaghi Philippon in Greece. In the UK, the Hoxnian Interglacial has been considered to correlate with MIS 11. New investigations at Hoxne (Suffolk) provide an opportunity to re-evaluate the terrestrial record of MIS 11. At Hoxne, the type Hoxnian Interglacial sediments are overlain by a post-Hoxnian cold-temperate sequence. The interglacial sediments and the later temperate phase are separated by the so-called ‘Arctic Bed’ from which cold-climate macroscopic plant and beetle remains have been recovered. -

JOHN WYMER Copyright © British Academy 2007 – All Rights Reserved

JOHN WYMER Jim Rose Copyright © British Academy 2007 – all rights reserved John James Wymer 1928–2006 ON A WET JUNE DAY IN 1997 a party of archaeologists met at the Swan in the small Suffolk village of Hoxne to celebrate a short letter that changed the way we understand our origins. Two hundred years before, the Suffolk landowner John Frere had written to the Society of Antiquaries of London about flint ‘weapons’ that had been dug up in the local brickyard. He noted the depth of the strata in which they lay alongside the bones of unknown animals of enormous size. He concluded with great prescience that ‘the situation in which these weapons were found may tempt us to refer them to a very remote period indeed; even beyond that of the present world’.1 Frere’s letter is now recognised as the starting point for Palaeolithic, old stone age, archaeology. In two short pages he identified stone tools as objects of curiosity in their own right. But he also reasoned that because of their geological position they were ‘fabricated and used by a people who had not the use of metals’.2 The bi-centenary gathering was organised by John Wymer who devoted his professional life to the study of the Palaeolithic and whose importance to the subject extended far beyond a brickpit in Suffolk. Wymer was the greatest field naturalist of the Palaeolithic. He had acute gifts of observation and an attention to detail for both artefacts and geol- ogy that was unsurpassed. He provided a typology and a chronology for the earliest artefacts of Britain and used these same skills to establish 1 R. -

Position of the Steinheim Interglacial Sequence Within the Marine Oxygen Isotope Record Based on Mammal Biostratigraphy

Quaternary International 292 (2013) 33e42 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Quaternary International journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/quaint Position of the Steinheim interglacial sequence within the marine oxygen isotope record based on mammal biostratigraphy Eline Naomi van Asperen*,1 Department of Archaeology, University of York, King’s Manor, York YO1 7EP, United Kingdom article info abstract Article history: Since the recovery, in 1933, of a Homo heidelbergensis skull from the interglacial Antiquus-Schotter in Available online 24 October 2012 sediments of the River Murr, the site of Steinheim (Germany) has been regarded as an iconic hominin locality for the Middle Pleistocene of Europe. Based on the morphology of the specimen, stratigraphical considerations and the characteristics of the associated faunal assemblage, the Steinheim skull has generally been assigned to the Holsteinian Interglacial. Over the last decades, developments in the knowledge of the complexity of the Pleistocene glacialeinterglacial cycles have rendered this date increasingly problematic. Analyses of caballoid horse remains from the site using log ratio diagrams and principal components analysis reveal striking morphological differences with German horse remains from sites attributed to the Holsteinian or marine isotope stages (MIS) 11 and 9. The morphology of the Steinheim horses is similar to that of horse specimens from MIS 9 sites in southern France, and to a lesser degree there are similarities with MIS 9 horses from northern France and British MIS 11 and 9 horse fossils. This indicates that during the Anglian/Elsterian glacial, European horse populations were split into two lineages. During MIS 11, the western lineage is present in the British Isles and at Steinheim, whereas the German Hol- steinian samples belong to the eastern lineage.