THE BRIAN MAY COLLECTION: Two Decades of Screen Composition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LS17.17022-Program-Web

ACTEWAGL LLEWELLYN SERIES CELLO The CSO is assisted by the Commonwealth Government through the Australia Council, its arts funding and advisory body New Combination “Bean” Lorry No.341 commissioned 31st December 1925. 115 YEARS OF POWERING PROGRESS TOGETHER Since 1901, Shell has invested in large projects which have contributed to the prosperity of the Australian economy. We value our partnerships with communities, governments and industry. And celebrate our longstanding partnership with the Canberra Symphony Orchestra. shell.com.au Photograph courtesy of The University of Melbourne Archives 2008.0045.0601 SHA3106__CSO_245x172_V3.indd 1 20/09/2016 2:53 PM ACTEWAGL LLEWELLYN SERIES CELLO Wednesday 17 May & Thursday 18 May, 2017 Llewellyn Hall, ANU 7.30pm Conductor Stanley Dodds Cello Umberto Clerici ----- HAYDN: Overture to L’isola disabitata (The Desert Island), Hob 28/9 8’ SCHUMANN: Cello Concerto in A minor, op. 129 25’ 1. Nicht zu schnell 2. Langsam 3. Sehr lebhaft INTERMISSION SCULTHORPE: String Sonata No. 3 (Jabiru Dreaming) 8’ 1 Deciso 2 Liberamente – Estatico BRAHMS: Symphony No. 3 in F major, op. 90 33’ 1. Allegro con brio 2. Andante 3. Poco allegretto 4. Allegro Please note: this program is correct at time of printing, however it is subject to change without notice. Umberto Clerici’s performance is supported by the Embassy of Italy in Canberra, Istituto Italiano di Cultura in Sydney and Schiavello enterprise Cover photo by Sarah Walker Sarah Cover photo by 17022 SEASON 2017 ActewAGL Llewellyn Series: Cello, Horn, Violin “Music -

For Release: on Approval Motion Picture Sound Editors to Honor

For Release: On Approval Motion Picture Sound Editors to Honor George Miller with Filmmaker Award 68th MPSE Golden Reel Awards to be held as a global, virtual event on April 16th Studio City, California – February 10, 2021 – The Motion Picture Sound Editors (MPSE) will honor Academy Award-winner George Miller with its annual Filmmaker Award. The Australian writer, director and producer is responsible for some of the most successful and beloved films of recent decades including Mad Max, Mad Max 2: Road Warrior, Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome and Mad Max: Fury Road. In 2007, he won the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature for the smash hit Happy Feet. He also earned Oscar nominations for Babe and Lorenzo’s Oil. Miller will be presented with the MPSE FilmmaKer Award at the 68th MPSE Golden Reel Awards, set for April 16th as an international virtual event. Miller is being honored for a career noteworthy for its incredibly broad scope and consistent excellence. “George Miller redefined the action genre through his Mad Max films, and he has been just as successful in bringing us such wonderfully different films as The Witches of Eastwick, Lorenzo’s Oil, Babe and Happy Feet,” said MPSE President MarK Lanza. “He represents the art of filmmaking at its best. We are proud to present him with MPSE’s highest honor.” Miller called the award “a lovely thing,” adding, “It’s a big pat on the back. I was originally drawn to film through the visual sense, but I learned to recognize sound, emphatically, as integral to the apprehension of the story. -

A Dark New World : Anatomy of Australian Horror Films

A dark new world: Anatomy of Australian horror films Mark David Ryan Faculty of Creative Industries, Queensland University of Technology A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the degree Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), December 2008 The Films (from top left to right): Undead (2003); Cut (2000); Wolf Creek (2005); Rogue (2007); Storm Warning (2006); Black Water (2007); Demons Among Us (2006); Gabriel (2007); Feed (2005). ii KEY WORDS Australian horror films; horror films; horror genre; movie genres; globalisation of film production; internationalisation; Australian film industry; independent film; fan culture iii ABSTRACT After experimental beginnings in the 1970s, a commercial push in the 1980s, and an underground existence in the 1990s, from 2000 to 2007 contemporary Australian horror production has experienced a period of strong growth and relative commercial success unequalled throughout the past three decades of Australian film history. This study explores the rise of contemporary Australian horror production: emerging production and distribution models; the films produced; and the industrial, market and technological forces driving production. Australian horror production is a vibrant production sector comprising mainstream and underground spheres of production. Mainstream horror production is an independent, internationally oriented production sector on the margins of the Australian film industry producing titles such as Wolf Creek (2005) and Rogue (2007), while underground production is a fan-based, indie filmmaking subculture, producing credit-card films such as I know How Many Runs You Scored Last Summer (2006) and The Killbillies (2002). Overlap between these spheres of production, results in ‘high-end indie’ films such as Undead (2003) and Gabriel (2007) emerging from the underground but crossing over into the mainstream. -

Joana Carneiro Music Director

JOANA CARNEIRO MUSIC DIRECTOR Berkeley Symphony 17/18 Season 5 Message from the Music Director 7 Message from the Board President 9 Message from the Executive Director 11 Board of Directors & Advisory Council 12 Orchestra 15 Season Sponsors 16 Berkeley Sound Composer Fellows & Full@BAMPFA 18 Berkeley Symphony 17/18 Calendar 21 Tonight’s Program 23 Program Notes 37 About Music Director Joana Carneiro 39 Guest Artists & Composers 43 About Berkeley Symphony 44 Music in the Schools 47 Berkeley Symphony Legacy Society 49 Annual Membership Support 58 Broadcast Dates 61 Contact 62 Advertiser Index Media Sponsor Gertrude Allen • Annette Campbell-White & Ruedi Naumann-Etienne Official Wine Margaret Dorfman • Ann & Gordon Getty • Jill Grossman Sponsor Kathleen G. Henschel & John Dewes • Edith Jackson & Thomas W. Richardson Sarah Coade Mandell & Peter Mandell • Tricia Swift S. Shariq Yosufzai & Brian James Presentation bouquets are graciously provided by Jutta’s Flowers, the official florist of Berkeley Symphony. Berkeley Symphony is a member of the League of American Orchestras and the Association of California Symphony Orchestras. No photographs or recordings of any part of tonight’s performance may be made without the written consent of the management of Berkeley Symphony. Program subject to change. October 5 & 6, 2017 3 4 October 5 & 6, 2017 Message from the Music Director Dear Friends, Happy New Season 17/18! I am delighted to be back in Berkeley after more than a year. There are three beautiful reasons for photo by Rodrigo de Souza my hiatus. I am so grateful for all the support I received from the Berkeley Symphony musicians, members of the Board and Advisory Council, the staff, and from all of you throughout this special period of my family’s life. -

East-West Film Journal, Volume 5, No. 1

EAST-WEST FILM JOURNAL VOLUME 5 . NUMBER 1 SPECIAL ISSUE ON MELODRAMA AND CINEMA Editor's Note I Melodrama/Subjectivity/Ideology: The Relevance of Western Melodrama Theories to Recent Chinese Cinema 6 E. ANN KAPLAN Melodrama, Postmodernism, and the Japanese Cinema MITSUHIRO YOSHIMOTO Negotiating the Transition to Capitalism: The Case of Andaz 56 PAUL WILLEMEN The Politics of Melodrama in Indonesian Cinema KRISHNA SEN Melodrama as It (Dis)appears in Australian Film SUSAN DERMODY Filming "New Seoul": Melodramatic Constructions of the Subject in Spinning Wheel and First Son 107 ROB WILSON Psyches, Ideologies, and Melodrama: The United States and Japan 118 MAUREEN TURIM JANUARY 1991 The East-West Center is a public, nonprofit educational institution with an international board of governors. Some 2,000 research fellows, grad uate students, and professionals in business and government each year work with the Center's international staff in cooperative study, training, and research. They examine major issues related to population, resources and development, the environment, culture, and communication in Asia, the Pacific, and the United States. The Center was established in 1960 by the United States Congress, which provides principal funding. Support also comes from more than twenty Asian and Pacific governments, as well as private agencies and corporations. Editor's Note UNTIL very recent times, the term melodrama was used pejoratively to typify inferior works of art that subscribed to an aesthetic of hyperbole and that were given to sensationalism and the crude manipulation of the audiences' emotions. However, during the last fifteen years or so, there has been a distinct rehabilitation of the term consequent upon a retheoriz ing of such questions as the nature of representation in cinema, the role of ideology, and female subjectivity in films. -

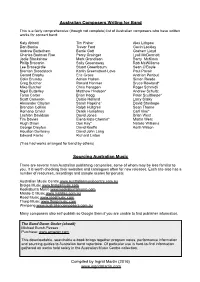

Australian Composers & Sourcing Music

Australian Composers Writing for Band This is a fairly comprehensive (though not complete) list of Australian composers who have written works for concert band: Katy Abbott Tim Fisher Alex Lithgow Don Banks Trevor Ford Gavin Lockley Andrew Batterham Barrie Gott Graham Lloyd Charles Bodman Rae Percy Grainger Lyall McDermott Jodie Blackshaw Mark Grandison Barry McKimm Philip Bracanin Sally Greenaway Rob McWilliams Lee Bracegirdle Stuart Greenbaum Sean O’Boyle Brenton Broadstock Karlin Greenstreet-Love Paul Pavoir Gerard Brophy Eric Gross Andrian Pertout Colin Brumby Adrian Hallam Simon Reade Greg Butcher Ronald Hanmer Bruce Rowland* Mike Butcher Chris Henzgen Roger Schmidli Nigel Butterley Matthew Hindson* Andrew Schultz Taran Carter Brian Hogg Peter Sculthorpe* Scott Cameron Dulcie Holland Larry Sitsky Alexander Clayton Sarah Hopkins* David Stanhope Brendan Collins Ralph Hultgren Sean Thorne Romano Crivici Derek Humphrey Carl Vine* Lachlan Davidson David Jones Brian West Tim Davies Elena Kats-Chernin* Martin West Hugh Dixon Don Kay* Natalie Williams George Dreyfus David Keeffe Keith Wilson Houston Dunleavy David John Lang Edward Fairlie Richard Linton (*has had works arranged for band by others) Sourcing Australian Music There are several main Australian publishing companies, some of whom may be less familiar to you. It is worth checking their websites and catalogues often for new releases. Each site also has a number of resources, recordings and sample scores for perusal. Australian Music Centre www.australianmusiccentre.com.au Brolga Music www.brolgamusic.com Kookaburra Music www.kookaburramusic.com Middle C Music www.middlec.com.au Reed Music www.reedmusic.com Thorp Music www.thorpmusic.com Wirripang www.australiancomposers.com.au Many composers also self-publish so Google them if you are unable to find publisher information. -

What Killed Australian Cinema & Why Is the Bloody Corpse Still Moving?

What Killed Australian Cinema & Why is the Bloody Corpse Still Moving? A Thesis Submitted By Jacob Zvi for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the Faculty of Health, Arts & Design, Swinburne University of Technology, Melbourne © Jacob Zvi 2019 Swinburne University of Technology All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. II Abstract In 2004, annual Australian viewership of Australian cinema, regularly averaging below 5%, reached an all-time low of 1.3%. Considering Australia ranks among the top nations in both screens and cinema attendance per capita, and that Australians’ biggest cultural consumption is screen products and multi-media equipment, suggests that Australians love cinema, but refrain from watching their own. Why? During its golden period, 1970-1988, Australian cinema was operating under combined private and government investment, and responsible for critical and commercial successes. However, over the past thirty years, 1988-2018, due to the detrimental role of government film agencies played in binding Australian cinema to government funding, Australian films are perceived as under-developed, low budget, and depressing. Out of hundreds of films produced, and investment of billions of dollars, only a dozen managed to recoup their budget. The thesis demonstrates how ‘Australian national cinema’ discourse helped funding bodies consolidate their power. Australian filmmaking is defined by three ongoing and unresolved frictions: one external and two internal. Friction I debates Australian cinema vs. Australian audience, rejecting Australian cinema’s output, resulting in Frictions II and III, which respectively debate two industry questions: what content is produced? arthouse vs. -

INSIDE the MUSICIAN: JOHN CLARE at 75 by John Clare*

INSIDE THE MUSICIAN: JOHN CLARE AT 75 by John Clare* __________________________________________________ INSIDE THE MUSICIAN is a series of articles on the Music Trust of Australia website by music people of all kinds, revealing something about their musical worlds and how they experience them. This article appeared on June 5, 2016. To read this on that website, go to this link http://musictrust.com.au/loudmouth/inside-the-musician-john-clare-75/ o come in from a wide or oblique angle, I need to apologise briefly that my writing is not what it was. There is no excuse, but a reason of sorts. Over the T past few years I have lost a son and a sister, the wonderful old Chinese lady upstairs who died and was replaced by a crazy and nasty woman who fire bombed my flat while I was visiting my daughter in Brisbane. And more, but we’ll leave that. Perhaps this stress and distress is behind my two strokes and a triple A operation (aortic aneurism in the aorta) which comprehensively relieved me of my memory for a while. Concentration is difficult and death seems often to be hovering. Yet strangely I am very fit and can race up very steep hills on my bike or grind up on the seat. It is when I am lying down and for some time afterward that it surrounds me. We’ll leave it at that. More important than that is how music sounds and what it means in what may well be the end days. Mine anyway. Like vapour trails soaring straight up at space from the horizon, or so it seems, but finding the curvature of the earth almost directly above. -

Amongst Friends: the Australian Cult Film Experience Renee Michelle Middlemost University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2013 Amongst friends: the Australian cult film experience Renee Michelle Middlemost University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Middlemost, Renee Michelle, Amongst friends: the Australian cult film experience, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of Social Sciences, Media and Communication, University of Wollongong, 2013. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/4063 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Amongst Friends: The Australian Cult Film Experience A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY From UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG By Renee Michelle MIDDLEMOST (B Arts (Honours) School of Social Sciences, Media and Communications Faculty of Law, Humanities and The Arts 2013 1 Certification I, Renee Michelle Middlemost, declare that this thesis, submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Department of Social Sciences, Media and Communications, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Renee Middlemost December 2013 2 Table of Contents Title 1 Certification 2 Table of Contents 3 List of Special Names or Abbreviations 6 Abstract 7 Acknowledgements 8 Introduction -

Mad Max, Reaganism and the Road Warrior

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Waterloo Library Journal Publishing Service (University of Waterloo, Canada) Mad Max, Reaganism and The Road Warrior By J. Emmett Winn Fall 1997 Issue of KINEMA IN 1981 THE AUSTRALIAN-MADE FILM The Road Warrior drove into the US film market.(1) The film was well received and quickly became, at that time, the most popular Australian movie ever releasedin the US, and since its debut has played regularly on US cable television.(2) Much has been written about the international success of this film and its predecessor, Mad Max, and the last in the trilogy Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome.(3) Contributing to that body of research, this paper addresses the American success of this Australian film within the cultural/political context of the US at the time of its North American release,and discusses its resonance with Reaganism. The fundamental goal of this examination is to situate the films in the larger context of cultural hegemony. The importance of this study lies in the critique of these films as they aid us in understanding the hegemonic process and the American box office triumph of The Road Warrior. I investigate how the trilogy in general, and The Road Warrior specifically, resonates with the social field of its time. These films entered the US during a period of renewed nationalistic interest and conservatism linked with the Reagan/Bush administrations. As Stuart Hall explains, the meanings of cultural products are partially provided by their time. In his article ”Notes on Deconstructing ’The Popular’” he states: The meaning of a cultural symbol is given in part by the social field into which it is incorporated, the practices which it articulates and is made to resonate. -

Evil Angels Aka Cry in the Dark Music Credits

Music Bruce Smeaton Music Mixer Martin Oswin Original Music Performed by Joe Chindamo & Loose Change Scoring Engineer Robin Gray Scored at Allan Eaton Sound Joe Chindamo and Loose Change were a jazz-inflected ensemble active in Melbourne during the 1980s. There is an interview with Chindamo online here which references that time: ...When he emerges, he’s carrying the Loose Change CD, ‘Live at the Grainstore’, recorded originally in the late ‘80s and re-released a few years ago on the Vorticity Music label here in Melbourne. Loose Change used to play at the Grainstore when I was working at the Health Commission—just a few short metres up King Street. I’m pretty sure I’ve heard them live… and was even more sure when he put the CD on and I recognised the sounds. Loose Change was Virgil Donati on drums, Steve Hadley on bass, Mark Domoney on guitar and of course Joe playing keyboards. “This is a kind of a jazz-rock band,” beams Joe over the sounds. “This is my former life… one of my former lives. And don’t forget, I played with Billy Cobham for ten years!” (Below: Joe Chindamo, and Loose Change’s one album release) Bruce Smeaton's score was eventually released on a German CD under the film's US and international title: CD Silva Screen/Edel Company Edel SIL 1527.2 The first five tracks were from the film, with the remaining tracks (6 to 18) featuring music from The Assault, The Rose Garden and The Naked Cage). 1. Main Titles (03'27") 2. -

Mad Max 11 Music Credits

Music Composed and Conducted by Brian May Music Mixed & recorded at A.A.V. Australia by Roger Savage Mad Max 2 probably represented the apogee of composer Brian May's work with director George Miller, and consequently his work for the film has been given any number of releases on LP and CD, under the film's Australian and US titles, and his score remains widely available: LP Thatʼs Entertainment (UK). TER 1016 1982 SIDE 1: Opening Titles/Montage Confrontation * Marauderʼs Massacre Max Enters Compound Feral Boy Strikes * Gyro Saves Max SIDE 2: Gyro Flight * Break Out The Chase Continues Break Out * Finale/Largo End Title Music * Includes sound effects from the film LP Milan (France) A 120 163 1982 Distribution: Suisse MTB AG France RCA Belgique Inelco SIDE 1: Montage - Main Title Confrontation Marauders Massacre Max Enters Compound Gyro Saves Max SIDE 2: Breakout Finale / Largo End Title SFX Suite LP (ST) Varese Sarabande (USA) STV 81155 1982 (CD VAR 47262) Producer for Varese Sarabande Records: Tom Null, Chris Kuchler Executive Producers: Scot W. Holton, John Sievers Mastering Engineer: Bruce Leek, Automated Media Manufactured at KM Records. KM Production Coordination: Mike Malan, Karen Stone SIDE 1: Montage / Main Title Confrontation Maraudersʼ Massacre Max Enters Compound Gyro Saves Max SIDE 2: Break Out Finale And Largo End Title SFX Suite: a. Boomerang Attack. b. Gyro Flight / The Big Rig Starts. c. Break Out / The Refinery Explodes / Reprise. UMGD/Varese Saraband VCD 47262, November 1988 1. Montage (Main Title from the Road Warrior (Mad Max 2) (5'53") 2. Confrontation (3'32") 3.