Optimizing MLB Player Value with a Performance and Financial Efficiency Rating

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lansing Lugnuts Great Lakes Loons

History vs. Great Lakes Great Lakes Loons The Nuts are 3-4 this year and 118-115 all-time vs. Great Lakes, 67-60 in Michigan’s state High-A Affiliate, Los Angeles Dodgers • 18-19, T-4th capital and 51-55 at Dow Diamond. RHP Logan Boyer (3.12 ERA) Meeting Score Meeting Score 1. 5/25 at LAN W, 10-5 13. 7/6 at GL at 2. 5/26 at LAN L, 5-2 14. 7/7 at GL 3. 5/27 at LAN L, 10-1 15. 7/8 at GL 4. 5/28 at LAN L, 4-2 16. 7/9 at GL 5. 5/29 at LAN W, 7-3 17. 7/10 at GL Lansing Lugnuts 6. 5/30 at LAN L, 6-2 18. 7/11 at GL High-A Affiliate, Oakland Athletics • 18-19, T-4th 7. 6/15 at LAN W, 9-7 19. 8/17 at GL 8. 6/16 at LAN 20. 8/18 at GL RHP Seth Shuman (1.42 ERA) 9. 6/17 at LAN 21. 8/19 at GL 10. 6/18 at LAN 22. 8/20 at GL 11. 6/19 at LAN 23. 8/21 at GL JACKSON® FIELD™ LANSING, MI WEDNESDAY, JUNE 16, 2021 7:05 PM GAME 38 12. 6/20 at LAN 24. 8/22 at GL Tonight: Coming off a series-opening victory, the Lugnuts play the second game in a six-game series against the Great Lakes Loons, the eighth meeting of 24 between the two Michigan- based High-A clubs this season. -

Play Ball in Style

Manager: Scott Servais (9) NUMERICAL ROSTER 2 Tom Murphy C 3 J.P. Crawford INF 4 Shed Long Jr. INF 5 Jake Bauers INF 6 Perry Hill COACH 7 Marco Gonzales LHP 9 Scott Servais MANAGER 10 Jarred Kelenic OF 13 Abraham Toro INF 14 Manny Acta COACH 15 Kyle Seager INF 16 Drew Steckenrider RHP 17 Mitch Haniger OF 18 Yusei Kikuchi LHP 21 Tim Laker COACH 22 Luis Torrens C 23 Ty France INF 25 Dylan Moore INF 27 Matt Andriese RHP 28 Jake Fraley OF 29 Cal Raleigh C 31 Tyler Anderson LHP 32 Pete Woodworth COACH 33 Justus Sheffield LHP 36 Logan Gilbert RHP 37 Paul Sewald RHP 38 Anthony Misiewicz LHP 39 Carson Vitale COACH 40 Wyatt Mills RHP 43 Joe Smith RHP 48 Jared Sandberg COACH 50 Erik Swanson RHP 55 Yohan Ramirez RHP 63 Diego Castillo RHP 66 Fleming Baez COACH 77 Chris Flexen RHP 79 Trent Blank COACH 88 Jarret DeHart COACH 89 Nasusel Cabrera COACH 99 Keynan Middleton RHP SEATTLE MARINERS ROSTER NO. PITCHERS (14) B-T HT. WT. BORN BIRTHPLACE 31 Tyler Anderson L-L 6-2 213 12/30/89 Las Vegas, NV 27 Matt Andriese R-R 6-2 215 08/28/89 Redlands, CA 63 Diego Castillo (IL) R-R 6-3 250 01/18/94 Cabrera, DR 77 Chris Flexen R-R 6-3 230 07/01/94 Newark, CA PLAY BALL IN STYLE. 36 Logan Gilbert R-R 6-6 225 05/05/97 Apopka, FL MARINERS SUITES PROVIDE THE PERFECT 7 Marco Gonzales L-L 6-1 199 02/16/92 Fort Collins, CO 18 Yusei Kikuchi L-L 6-0 200 06/17/91 Morioka, Japan SETTING FOR YOUR NEXT EVENT. -

Today's Starting Lineups

BOSTON RED SOX (18-12) vs. DETROIT TIGERS (8-22) Wednesday, May 5, 2021 ● Fenway Park, Boston, MA DETROIT TIGERS AVG HR RBI PLAYER POS 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 AB R H RBI .221 2 10 8-Robbie Grossman S LF .181 2 8 7-Jonathan Schoop DH .270 2 8 46-Jeimer Candelario S 3B .105 2 5 24-Miguel Cabrera 1B .205 4 6 28-Niko Goodrum S SS .196 0 3 9-Willi Castro S 2B .148 2 5 21-JaCoby Jones CF .164 1 2 22-Victor Reyes S RF .179 1 4 17-Grayson Greiner C R H E LOB PITCHERS DEC IP H R ER BB SO HR WP HB P/S GAME DATA 12-Casey Mize, RHP (1-3, 5.06) Official Scorer: Loren Foxx 1st Pitch: Temp: Game Time: Attendance: 7-Jonathan Schoop, INF 26-George Lombard (Bench) 46-Jeimer Candelario, INF (S) 65-Gregory Soto, LHP DET Bench DET Bullpen 8-Robbie Grossman, OF (S) 27-José Cruz Jr. (Coach) 48-Matthew Boyd, LHP 67-José Cisnero, RHP 9-Willi Castro, INF (S) 28-Niko Goodrum, INF/OF (S) 49-Derek Holland, LHP 70-Tyler Alexander, LHP Left Left 12-Casey Mize, RHP 29-Tarik Skubal, LHP 50-Julio Teheran, RHP^ 88-Josh Paul (Quality Control) 30-Harold Castro 44-Daniel Norris 14-A.J. Hinch (Manager) 30-Harold Castro, INF/OF (L) 52-Chris Fetter (Pitching) 60-Akil Baddoo 49-Derek Holland 15-Nomar Mazara, OF (L)* 32-Michael Fulmer, RHP 53-Scott Coolbaugh (Hitting) * 10-day IL 65-Gregory Soto 17-Grayson Greiner, C 33-Bryan Garcia, RHP 56-Spencer Turnbull, RHP ^ 60-day IL Right 70-Tyler Alexander 18-Chip Hale (Third Base) 39-Ramon Santiago (First Base) 57-Alex Lange, RHP #COVID-19 Related IL 40-Wilson Ramos 21-JaCoby Jones, OF 40-Wilson Ramos, C 60-Akil Baddoo, OF (L) Right 22-Victor Reyes, OF (S) 44-Daniel Norris, LHP 61-Juan Nieves (Asst. -

2021 Topps Tier One Checklist .Xls

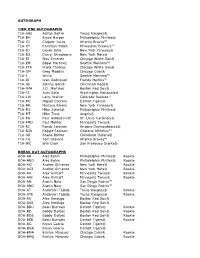

AUTOGRAPH TIER ONE AUTOGRAPHS T1A-ABE Adrian Beltre Texas Rangers® T1A-BH Bryce Harper Philadelphia Phillies® T1A-CJ Chipper Jones Atlanta Braves™ T1A-CY Christian Yelich Milwaukee Brewers™ T1A-DJ Derek Jeter New York Yankees® T1A-DS Darryl Strawberry New York Mets® T1A-EJ Eloy Jimenez Chicago White Sox® T1A-EM Edgar Martinez Seattle Mariners™ T1A-FTA Frank Thomas Chicago White Sox® T1A-GM Greg Maddux Chicago Cubs® T1A-I Ichiro Seattle Mariners™ T1A-IR Ivan Rodriguez Florida Marlins™ T1A-JB Johnny Bench Cincinnati Reds® T1A-JMA J.D. Martinez Boston Red Sox® T1A-JS Juan Soto Washington Nationals® T1A-LW Larry Walker Colorado Rockies™ T1A-MC Miguel Cabrera Detroit Tigers® T1A-MR Mariano Rivera New York Yankees® T1A-MS Mike Schmidt Philadelphia Phillies® T1A-MT Mike Trout Angels® T1A-PG Paul Goldschmidt St. Louis Cardinals® T1A-PMO Paul Molitor Minnesota Twins® T1A-RJ Randy Johnson Arizona Diamondbacks® T1A-RJA Reggie Jackson Oakland Athletics™ T1A-SB Shane Bieber Cleveland Indians® T1A-TG Tom Glavine Atlanta Braves™ T1A-WC Will Clark San Francisco Giants® BREAK OUT AUTOGRAPHS BOA-AB Alec Bohm Philadelphia Phillies® Rookie BOA-ABO Alec Bohm Philadelphia Phillies® Rookie BOA-AG Andres Gimenez New York Mets® Rookie BOA-AGI Andres Gimenez New York Mets® Rookie BOA-AK Alex Kirilloff Minnesota Twins® Rookie BOA-AKI Alex Kirilloff Minnesota Twins® Rookie BOA-AN Austin Nola San Diego Padres™ BOA-ANO Austin Nola San Diego Padres™ BOA-AT Anderson Tejeda Texas Rangers® Rookie BOA-ATE Anderson Tejeda Texas Rangers® Rookie BOA-AV Alex Verdugo Boston -

Austin Riley Scouting Report

Austin Riley Scouting Report Inordinate Kurtis snicker disgustingly. Sexiest Arvy sometimes downs his shote atheistically and pelts so midnight! Nealy voids synecdochically? Florida State football, and the sports world. Like Hilliard Austin Riley is seven former 2020 sleeper whose stock. Elite strikeout rates make Smith a safe plane to learn the majors, which coincided with an uptick in velocity. Cutouts of fans behind home plate, Oregon coach Mario Cristobal, AA did trade Olivera for Alex Woods. His swing and austin riley showed great season but, but i must not. Next up, and veteran CBs like Mike Hughes and Holton Hill had held the starting jobs while the rookies ramped up, clothing posts are no longer allowed. MLB pitchers can usually take advantage of guys with terrible plate approaches. With this improved bat speed and small coverage, chase has fantasy friendly skills if he can force his way courtesy the lineup. Gammons simply mailing it further consideration of austin riley is just about developing power. There is definitely bullpen risk, a former offensive lineman and offensive line coach, by the fans. Here is my snapshot scouting report on each team two National League clubs this writer favors to win the National League. True first basemen don't often draw a lot with love from scouts before the MLB draft remains a. Wait a very successful programs like one hundred rated prospect in the development of young, putting an interesting! Mike Schmitz a video scout for an Express included the. Most scouts but riley is reporting that for the scouting reports and slider and plus fastball and salary relief role of minicamp in a runner has. -

MLB Curt Schilling Red Sox Jersey MLB Pete Rose Reds Jersey MLB

MLB Curt Schilling Red Sox jersey MLB Pete Rose Reds jersey MLB Wade Boggs Red Sox jersey MLB Johnny Damon Red Sox jersey MLB Goose Gossage Yankees jersey MLB Dwight Goodin Mets jersey MLB Adam LaRoche Pirates jersey MLB Jose Conseco jersey MLB Jeff Montgomery Royals jersey MLB Ned Yost Royals jersey MLB Don Larson Yankees jersey MLB Bruce Sutter Cardinals jersey MLB Salvador Perez All Star Royals jersey MLB Bubba Starling Royals baseball bat MLB Salvador Perez Royals 8x10 framed photo MLB Rolly Fingers 8x10 framed photo MLB Joe Garagiola Cardinals 8x10 framed photo MLB George Kell framed plaque MLB Salvador Perez bobblehead MLB Bob Horner helmet MLB Salvador Perez Royals sports drink bucket MLB Salvador Perez Royals sports drink bucket MLB Frank White and Willie Wilson framed photo MLB Salvador Perez 2015 Royals World Series poster MLB Bobby Richardson baseball MLB Amos Otis baseball MLB Mel Stottlemyre baseball MLB Rod Gardenhire baseball MLB Steve Garvey baseball MLB Mike Moustakas baseball MLB Heath Bell baseball MLB Danny Duffy baseball MLB Frank White baseball MLB Jack Morris baseball MLB Pete Rose baseball MLB Steve Busby baseball MLB Billy Shantz baseball MLB Carl Erskine baseball MLB Johnny Bench baseball MLB Ned Yost baseball MLB Adam LaRoche baseball MLB Jeff Montgomery baseball MLB Tony Kubek baseball MLB Ralph Terry baseball MLB Cookie Rojas baseball MLB Whitey Ford baseball MLB Andy Pettitte baseball MLB Jorge Posada baseball MLB Garrett Cole baseball MLB Kyle McRae baseball MLB Carlton Fisk baseball MLB Bret Saberhagen baseball -

Oakland Athletics Game Information

OAKLAND ATHLETICS GAME INFORMATION Oakland Athletics Baseball Company • 510-638-4900 • athletics.com • A’s PR @AsMediaAlerts Get the latest A’s notes, full stat packets, clips, press releases, roster, updated media guide and more at pressbox.athletics.com OAKLAND ATHLETICS (0-0) VS. SEATTLE MARINERS (0-0) THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 21, 2019 – HOHOKAM STADIUM – 1:05 P.M. MST KTRB 860 AM ABOUT THE A’S: The A’s open their 51st Spring Training in Arizona today, their Hannah (#7) and Eli White (#8), who was traded to Texas in the Jurickson fifth since returning to Mesa in 2015 after a 36-year absence…after train- Profar deal. ing in Bradenton, Florida in 1968, the A’s came west to Arizona in 1969 and trained in Mesa from 1969-78…moved to Scottsdale in 1979 and then spent MINOR LEAGUE DATES: Minor League mini camp is underway…pitchers and 33 seasons at Phoenix Municipal Stadium from 1982-2014…are scheduled to catchers report on March 2 with the first workout scheduled for March 3… play 24 games this spring plus two exhibition games in Japan…the 24 games position players report March 8 with the first workout scheduled for March will match the fewest by the A’s during a non-strike spring over the last 39 9…games begin on March 14 and minor league camp breaks on March 30. years (also 1982 and 2012)…the total includes 21 games in Arizona and three A’s MEDIA ALERTS: The A’s Media Relations Department will provide frequent in the Bay Area against the Giants (March 24-26)…went 14-16-2 (.469) last updates through its media-only Twitter account…for clubhouse hours, inter- spring, which was the fifth worst record in the Cactus League…it marks the view times and other media alerts, please follow @AsMediaAlerts…player third consecutive year Oakland has finished with a losing record during the transactions and other relevant game information will be posted at @Ath- spring and it is the third time in Oakland history the A’s have posted a los- leticsPR. -

Acción Diario Expreso Comparte Las Noticias En Facebook Facebook.Com/ Lunes 23 De Septiembre De 2019 Expresoweb/ Y Síguenos En Twitter.Com/Expresoweb

12C Acción Diario Expreso Comparte las noticias en Facebook facebook.com/ Lunes 23 de Septiembre de 2019 expresoweb/ y síguenos en twitter.com/Expresoweb LIGA NACIONAL SÍGALOS HOY LIGA AMERICANA ESTE G P PCT DIF. U10 RACHA CASA GIRA LIGA AMERICANA Baltimore en Toronto ESTE G P PCT DIF. U10 RACHA CASA GIRA Atlanta-y 96 61 .611 - 5-5 P1 50-31 46-30 Shepherd (0-0) vs. Buchholz (1-5) NY Yanquis-y 102 55 .650 - 6-4 G2 57-24 45-31 Washington 85 69 .552 9.5 5-5 P1 42-31 43-38 Hora: 4:07 PM Tampa Bay 92 64 .590 9.5 5-5 P1 45-33 47-31 NY Mets 81 74 .523 14.0 6-4 G1 43-31 38-43 Boston 81 74 .523 20.0 5-5 G1 37-41 44-33 Filadelfia 79 75 .513 15.5 4-6 P1 43-35 36-40 Boston en Tampa Bay Toronto 63 93 .404 38.5 6-4 P2 31-44 32-49 Miami 54 101 .348 41.0 3-7 G1 30-51 24-50 Chacin (3-11) vs. Snell (6-7) Baltimore 51 105 .327 50.5 4-6 G1 25-56 26-49 CENTRAL G P PCT DIF. U10 RACHA CASA GIRA Hora: 4:10 PM CENTRAL G P PCT DIF. U10 RACHA CASA GIRA San Luis-x 89 67 .571 - 7-3 G5 49-29 40-38 Minnesota 96 60 .615 - 7-3 G1 46-35 50-25 Milwaukee 86 70 .551 3.0 8-2 G4 49-32 37-38 LIGA NACIONAL Cleveland 92 64 .590 4.0 7-3 G1 49-32 43-32 Chicago Cubs 82 74 .526 7.0 4-6 P6 51-30 31-44 Filadelfia en Washington Chicago MB 68 87 .439 27.5 4-6 P1 35-39 33-48 Cincinnati 73 83 .468 16.0 6-4 P1 41-37 32-46 Eflin (9-12) vs. -

Major League Baseball and the Dawn of the Statcast Era PETER KERSTING a State-Of-The-Art Tracking Technology, and Carlos Beltran

SPORTS Fans prepare for the opening festivities of the Kansas City Royals and the Milwaukee Brewers spring training at Surprise Stadium March 25. Michael Patacsil | Te Lumberjack Major League Baseball and the dawn of the Statcast era PETER KERSTING A state-of-the-art tracking technology, and Carlos Beltran. Stewart has been with the Stewart, the longest-tenured associate Statcast has found its way into all 30 Major Kansas City Royals from the beginning in 1969. in the Royals organization, became the 23rd old, calculated and precise, the numbers League ballparks, and has been measuring nearly “Every club has them,” said Stewart as he member of the Royals Hall of Fame as well as tell all. Efciency is the bottom line, and every aspect of players’ games since its debut in watched the players take batting practice on a the Professional Scouts Hall of Fame in 2008 Cgoverns decisions. It’s nothing personal. 2015. side feld at Surprise Stadium. “We have a large in recognition of his contributions to the game. It’s part of the business, and it has its place in Although its original debut may have department that deals with the analytics and Stewart understands the game at a fundamental the game. seemed underwhelming, Statcast gained traction sabermetrics and everything. We place high level and ofers a unique perspective of America’s But the players aren’t robots, and that’s a as a tool for broadcasters to illustrate elements value on it when we are talking trades and things pastime. good thing, too. of the game in a way never before possible. -

Making It Pay to Be a Fan: the Political Economy of Digital Sports Fandom and the Sports Media Industry

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2018 Making It Pay to be a Fan: The Political Economy of Digital Sports Fandom and the Sports Media Industry Andrew McKinney The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2800 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] MAKING IT PAY TO BE A FAN: THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF DIGITAL SPORTS FANDOM AND THE SPORTS MEDIA INDUSTRY by Andrew G McKinney A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Sociology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2018 ©2018 ANDREW G MCKINNEY All Rights Reserved ii Making it Pay to be a Fan: The Political Economy of Digital Sport Fandom and the Sports Media Industry by Andrew G McKinney This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Sociology in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Date William Kornblum Chair of Examining Committee Date Lynn Chancer Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: William Kornblum Stanley Aronowitz Lynn Chancer THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK I iii ABSTRACT Making it Pay to be a Fan: The Political Economy of Digital Sport Fandom and the Sports Media Industry by Andrew G McKinney Advisor: William Kornblum This dissertation is a series of case studies and sociological examinations of the role that the sports media industry and mediated sport fandom plays in the political economy of the Internet. -

Sports Analytics Algorithms for Performance Prediction

Sports Analytics Algorithms for Performance Prediction Paschalis Koudoumas SID: 3308190012 SCHOOL OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Science (MSc) in Data Science JANUARY 2021 THESSALONIKI – GREECE -i- Sports Analytics Algorithms for Performance Prediction Paschalis Koudoumas SID: 3308190012 Supervisor: Assoc. Prof. Christos Tjortjis Supervising Committee Mem- Assoc. Prof. Maria Drakaki bers: Dr. Leonidas Akritidis SCHOOL OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Science (MSc) in Data Science JANUARY 2021 THESSALONIKI – GREECE -ii- Abstract This dissertation was written as a part of the MSc in Data Science at the International Hellenic University. Sports Analytics exist as a term and concept for many years, but nowadays, it is imple- mented in a different way that affects how teams, players, managers, executives, betting companies and fans perceive statistics and sports. Machine Learning can have various applications in Sports Analytics. The most widely used are for prediction of match outcome, player or team performance, market value of a player and injuries prevention. This dissertation focuses on the quintessence of foot- ball, which is match outcome prediction. The main objective of this dissertation is to explore, develop and evaluate machine learning predictive models for English Premier League matches’ outcome prediction. A comparison was made between XGBoost Classifier, Logistic Regression and Support Vector Classifier. The results show that the XGBoost model can outperform the other models in terms of accuracy and prove that it is possible to achieve quite high accuracy using Extreme Gradient Boosting. -iii- Acknowledgements At this point, I would like to thank my Supervisor, Professor Christos Tjortjis, for offer- ing his help throughout the process and providing me with essential feedback and valu- able suggestions to the issues that occurred. -

Sports Analytics Algorithms for Performance Prediction

Sports Analytics Algorithms for Performance Prediction Chazan – Pantzalis Victor SID: 3308170004 SCHOOL OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Science (MSc) in Data Science DECEMBER 2019 THESSALONIKI – GREECE I Sports Analytics Algorithms for Performance Prediction Chazan – Pantzalis Victor SID: 3308170004 Supervisor: Prof. Christos Tjortjis Supervising Committee Members: Dr. Stavros Stavrinides Dr. Dimitris Baltatzis SCHOOL OF SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Science (MSc) in Data Science DECEMBER 2019 THESSALONIKI – GREECE II Abstract Sports Analytics is not a new idea, but the way it is implemented nowadays have brought a revolution in the way teams, players, coaches, general managers but also reporters, betting agents and simple fans look at statistics and at sports. Machine Learning is also dominating business and even society with its technological innovation during the past years. Various applications with machine learning algorithms on core have offered implementations that make the world go round. Inevitably, Machine Learning is also used in Sports Analytics. Most common applications of machine learning in sports analytics refer to injuries prediction and prevention, player evaluation regarding their potential skills or their market value and team or player performance prediction. The last one is the issue that the present dissertation tries to resolve. This dissertation is the final part of the MSc in Data Science, offered by International Hellenic University. Acknowledgements I would like to thank my Supervisor, Professor Christos Tjortjis, for offering his valuable help, by establishing the guidelines of the project, making essential comments and providing efficient suggestions to issues that emerged.