Evolution of Character: St Helier Urban Character Appraisal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Liturgical Year 2020 of the Celtic Orthodox Church Wednesday 1St

Liturgical Year 2020 of the Celtic Orthodox Church Wednesday 1st January 2020 Holy Name of Jesus Circumcision of Our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ Basil the Great, Bishop of Caesarea of Palestine, Father of the Church (379) Beoc of Lough Derg, Donegal (5th or 6th c.) Connat, Abbess of St. Brigid’s convent at Kildare, Ireland (590) Ossene of Clonmore, Ireland (6th c.) ♦ Liturgy: Wis 3:10-19 Eph 3:1-7 Lk 6:5-11 Holy Name of Jesus: ♦ Vespers: Ps 8 and 19 ♦ 1st Nocturn: Ps 64 1Tm 2:1-6 Lk 6:16-22 ♦ 3rd Nocturn: Ps 71 and 134 Phil 2:6-11 ♦ Matins: Jn 10:9-16 ♦ Liturgy: Gn 17:1-14 Ps 112 Col 2:8-12 Lk 2:20-21 ♦ Sext: Ps 53 ♦ None: Ps 148 1 Thursday 2 January 2020 Seraphim, priest-monk of Sarov (1833) Adalard, Abbot of Corbie, Founder of New Corbie (827) John of Kronstadt, priest and confessor (1908) Seiriol, Welsh monk and hermit at Anglesey, off the coast of north Wales (early 6th c.) Munchin, monk, Patron of Limerick, Ireland (7th c.) The thousand Lichfield Christians martyred during the reign of Diocletian (c. 333) ♦ Liturgy: Wis 4:1-6 Eph 3:8-13 Lk 8:24-36 Friday 3 January 2020 Genevieve, virgin, Patroness of Paris (502) Blimont, monk of Luxeuil, 3rd Abbot of Leuconay (673) Malachi, prophet (c. 515 BC) Finlugh, Abbot of Derry (6th c.) Fintan, Abbot and Patron Saint of Doon, Limerick, Ireland (6th c.) ♦ Liturgy: Wis 4:7-14a Eph 3:14-21 Lk 6:46-49 Saturday 4 January 2020 70 Disciples of Our Lord Jesus Christ Gregory, Bishop of Langres (540) ♦ Liturgy: Wis 4:14b-20 Eph 4:1-16 Lk 7:1-10 70 Disciples: Lk 10:1-5 2 Sunday 5 January 2020 (Forefeast of the Epiphany) Syncletica, hermit in Egypt (c. -

Be a Time Traveller This Summer

BE A TIME TRAVELLER THIS SUMMER 50 THINGS YOU COULD DO THIS SUMMER: Spy for Wall Lizards at ✓ Take an Ice ✓ 1 Mont Orgueil Castle 14 Age Trail* 2 Eat a Jersey Wonder ✓ Find ten French ✓ 15 road names Crawl into the Neolithic Visit a Société Jersiaise ✓ 3 Passage Grave at ✓ 16 Dolmen* La Hougue Bie Listen to the Goodwyf ✓ Discover the 17 at Hamptonne 4 Celtic Coin Hoard ✓ at Jersey Museum Meet George, the 100 year ✓ 18 old tortoise at Durrell Visit the Ice Age 5 ✓ Dig at Les Varines (July)* Download the Jersey Heritage ✓ 19 Digital Pocket Museum 6 Visit 16 New Street ✓ 20 See the Devil at Devil’s Hole ✓ Sing Jèrriais with the Make a Papier-mâché 7 Badlabecques* ✓ 21 ✓ www.jerseyheritage.org/kids dinosaur at home Count the rings on a tree Draw your favourite ✓ 22 ✓ 8 place in Jersey stump to see how old it is Search for gun-shot marks Climb to the top ✓ 23 ✓ 9 of a castle in the Royal Square Discover Starry Starry Nights Look out for 24 ✓ the Perseid at La Hougue Bie 3 August 10 ✓ Meteor Shower Explore the Globe Room at ✓ August 11-13 25 the Maritime Museum 11 Picnic at Grosnez Castle ✓ Look for the Black Dog 12 of Bouley Bay at the ✓ Maritime Museum See the Noon Day Gun at 13 ✓ Elizabeth Castle For more details about these fun activities, visit www.jerseyheritage.org/kids *Free Guide & videos on the Jersey Heritage website Try abseiling with Castle ✓ Catch Lillie, Major Peirson & ✓ 26 Adventures 41 Terence - Le Petit Trains Dress up as a princess or Look for the rare Bosdet 27 ✓ soldier at Mont Orgueil Castle 42 painting at St -

NEW JERSEY History GUIDE

NEW JERSEY HISTOry GUIDE THE INSIDER'S GUIDE TO NEW JERSEY'S HiSTORIC SitES CONTENTS CONNECT WITH NEW JERSEY Photo: Battle of Trenton Reenactment/Chase Heilman Photography Reenactment/Chase Heilman Trenton Battle of Photo: NEW JERSEY HISTORY CATEGORIES NEW JERSEY, ROOTED IN HISTORY From Colonial reenactments to Victorian architecture, scientific breakthroughs to WWI Museums 2 monuments, New Jersey brings U.S. history to life. It is the “Crossroads of the American Revolution,” Revolutionary War 6 home of the nation’s oldest continuously Military History 10 operating lighthouse and the birthplace of the motion picture. New Jersey even hosted the Industrial Revolution 14 very first collegiate football game! (Final score: Rutgers 6, Princeton 4) Agriculture 19 Discover New Jersey’s fascinating history. This Multicultural Heritage 22 handbook sorts the state’s historically significant people, places and events into eight categories. Historic Homes & Mansions 25 You’ll find that historic landmarks, homes, Lighthouses 29 monuments, lighthouses and other points of interest are listed within the category they best represent. For more information about each attraction, such DISCLAIMER: Any listing in this publication does not constitute an official as hours of operation, please call the telephone endorsement by the State of New Jersey or the Division of Travel and Tourism. numbers provided, or check the listed websites. Cover Photos: (Top) Battle of Monmouth Reenactment at Monmouth Battlefield State Park; (Bottom) Kingston Mill at the Delaware & Raritan Canal State Park 1-800-visitnj • www.visitnj.org 1 HUnterdon Art MUseUM Enjoy the unique mix of 19th-century architecture and 21st- century art. This arts center is housed in handsome stone structure that served as a grist mill for over a hundred years. -

The Jersey Heritage Answersheet

THE JERSEY HERITAGE Monuments Quiz ANSWERSHEET 1 Seymour Tower, Grouville Seymour Tower was built in 1782, 1¼ miles offshore in the south-east corner of the Island. Jersey’s huge tidal range means that the tower occupies the far point which dries out at low tide and was therefore a possible landing place for invading troops. The tower is defended by musket loopholes in the walls and a gun battery at its base. It could also provide early warning of any impending attack to sentries posted along the shore. 2 Faldouet Dolmen, St Martin This megalithic monument is also known as La Pouquelaye de Faldouët - pouquelaye meaning ‘fairy stones’ in Jersey. It is a passage grave built in the middle Neolithic period, around 4000 BC, the main stones transported here from a variety of places up to three miles away. Human remains were found here along with finds such as pottery vessels and polished stone axes. 3 Cold War Bunker, St Helier A German World War II bunker adapted for use during the Cold War as Jersey’s Civil Emergency Centre and Nuclear Monitoring Station. The building includes a large operations room and BBC studio. 4 Statue of King George V in Howard Davis Park Bronze statue of King George V wearing the robes of the Sovereign of the Garter. Watchtower, La Coupe Point, St Martin 5 On the highest point of the headland is a small watchtower built in the early 19th century and used by the Royal Navy as a lookout post during the Napoleonic wars. It is sturdily constructed of mixed stone rubble with a circular plan and domed top in brick. -

Outline History of AJCA-NAJ

AMERICAN JERSEY CATTLE ASSOCIATION NATIONAL ALL-JERSEY INC. ALL-JERSEY SALES CORPORATION Outline History of Jerseys and the U.S. Jersey Organizations 1851 First dairy cow registered in America, a Jersey, Lily No. 1, Washington, goes national. born. 1956 A second all-donation sale, the All-American Sale of Starlets, 1853 First recorded butter test of Jersey cow, Flora 113, 511 lbs., 2 raises funds for an expanded youth program. oz. in 50 weeks. 1957 National All-Jersey Inc. organized. 1868 The American Jersey Cattle Club organized, the first national 1958 The All American Jersey Show and Sale revived after seven- dairy registration organization in the United States. year hiatus, with the first AJCC-managed National Jersey 1869 First Herd Register published and Constitution adopted. Jug Futurity staged the following year. 1872 First Scale of Points for evaluating type adopted. 1959 Dairy Herd Improvement Registry (DHIR) adopted to 1880 The AJCC incorporated April 19, 1880 under a charter recognize electronically processed DHIA records as official. granted by special act of the General Assembly of New York. All-Jersey® trademark sales expand to 28 states. Permanent offices established in New York City. 1960 National All-Jersey Inc. initiates the 5,000 Heifers for Jersey 1892 First 1,000-lb. churned butterfat record made (Signal’s Lily Promotion Project, with sale proceeds from donated heifers Flag). used to promote All-Jersey® program growth and expanded 1893 In competition open to all dairy breeds at the World’s field service. Columbian Exposition in Chicago, the Jersey herd was first 1964 Registration, classification and testing records converted to for economy of production; first in amount of milk produced; electronic data processing equipment. -

O C E a N O C E a N C T I C P a C I F I C O C E a N a T L a N T I C O C E a N P a C I F I C N O R T H a T L a N T I C a T L

Nagurskoye Thule (Qanaq) Longyearbyen AR CTIC OCE AN Thule Air Base LAPTEV GR EENLA ND SEA EAST Resolute KARA BAFFIN BAY Dikson SIBERIAN BARENTS SEA SEA SEA Barrow SEA BEAUFORT Tiksi Prudhoe Bay Vardo Vadso Tromso Kirbey Mys Shmidta Tuktoyaktuk Narvik Murmansk Norilsk Ivalo Verkhoyansk Bodo Vorkuta Srednekolymsk Kiruna NORWEGIAN Urengoy Salekhard SEA Alaska Oulu ICELA Anadyr Fairbanks ND Arkhangelsk Pechora Cape Dorset Godthab Tura Kitchan Umea Severodvinsk Reykjavik Trondheim SW EDEN Vaasa Kuopio Yellowknife Alesund Lieksa FINLAND Plesetsk Torshavn R U S S Yakutsk BERING Anchorage Surgut I A NORWAY Podkamennaya Tungusk Whitehorse HUDSON Nurssarssuaq Bergen Turku Khanty-Mansiysk Apuka Helsinki Olekminsk Oslo Leningrad Magadan Yurya Churchill Tallin Stockholm Okhotsk SEA Juneau Kirkwall ESTONIA Perm Labrador Sea Goteborg Yedrovo Kostroma Kirov Verkhnaya Salda Aldan BAY UNITED KINGDOM Aluksne Yaroslavl Nizhniy Tagil Aberdeen Alborg Riga Ivanovo SEA Kalinin Izhevsk Sverdlovsk Itatka Yoshkar Ola Tyumen NORTH LATVIA Teykovo Gladkaya Edinburgh DENMARK Shadrinsk Tomsk Copenhagen Moscow Gorky Kazan OF BALTIC SEA Cheboksary Krasnoyarsk Bratsk Glasgow LITHUANIA Uzhur SEA Esbjerg Malmo Kaunas Smolensk Kaliningrad Kurgan Novosibirsk Kemerovo Belfast Vilnius Chelyabinsk OKHOTSK Kolobrzeg RUSSIA Ulyanovsk Omsk Douglas Tula Ufa C AN Leeds Minsk Kozelsk Ryazan AD A Gdansk Novokuznetsk Manchester Hamburg Tolyatti Magnitogorsk Magdagachi Dublin Groningen Penza Barnaul Shefeld Bremen POLAND Edmonton Liverpool BELARU S Goose Bay NORTH Norwich Assen Berlin -

Download the Full Jersey ILSCA Report

Jersey Integrated Landscape and Seascape Character Assessment Prepared for Government of Jersey by Fiona Fyfe Associates May 2020 www.fionafyfe.co.uk Jersey Integrated Landscape and Seascape Character Assessment Acknowledgements Acknowledgements The lead consultant would like to thank all members of the client team for their contributions to the project. Particular thanks are due to the Government of Jersey staff who accompanied field work and generously shared their time and local knowledge. This includes the skipper and crew of FPV Norman Le Brocq who provided transport to the reefs and marine areas. Thanks are also due to the many local stakeholders who contributed helpfully and willingly to the consultation workshop. Innovative and in-depth projects such as this require the combined skills of many professionals. This project had an exceptional consultant team and the lead consultant would like to thank them all for their superb contributions. She would particularly like to acknowledge the contribution of Tom Butlin (1982- 2020) for his outstanding and innovative work on the visibility mapping. • Jonathan Porter and Tom Butlin (Countryscape) • Carol Anderson (Carol Anderson Landscape Associates) • Nigel Buchan (Buchan Landscape Architecture) • Douglas Harman (Douglas Harman Landscape Planning) All photographs have been taken by Fiona Fyfe unless otherwise stated. Carol Anderson Landscape Associates ii FINAL May 2020 Prepared by Fiona Fyfe Associates for Government of Jersey Jersey Integrated Landscape and Seascape Character Assessment Foreword Ministerial Foreword It gives me tremendous pleasure to introduce the Jersey Integrated Landscape and Seascape Character Assessment which has been commissioned for the review of the 2011 Island Plan. Jersey’s coast and countryside is a unique and precious asset, which is treasured by islanders and is one of the key reasons why people visit the island. -

R.134-2011 Fort Regent Political Steering Group- Interim Report

STATES OF JERSEY FORT REGENT POLITICAL STEERING GROUP: INTERIM REPORT Presented to the States on 8th November 2011 by the Minister for Education, Sport and Culture STATES GREFFE 2011 Price code: C R.134 2 REPORT Steering Group members: Deputy J.G. Reed of St. Ouen (Chairman) Senator P.F. Routier Connétable J.M. Refault of St. Peter Deputy R.C. Duhamel of St. Saviour Deputy T.M. Pitman of St. Helier Connétable A.S. Crowcroft of St. Helier Executive Summary Two issues have dominated past discussions about the future of Fort Regent – funding and access. Realistically, there can be no development of the centre on a major scale until these 2 issues are addressed. Accordingly, the Steering Group has compiled an action plan that identifies the next steps. It was clear from the start of this process that further detailed work would be required and it was also clear that this would take time. The Steering Group has been able to pinpoint the next investigations that will be required and the bodies who are able to move this project forward. We have also identified realistic actions that can benefit Fort Regent immediately, be achieved in the short term and do not require significant expenditure. These steps, although small, will help improve the current facility while more detailed work is carried out on medium- and long-term objectives. All the points are set out in an Action Plan in section 5 of this report according to the timescale in which they are achievable. Over and above this plan, the Steering Group has been able to identify a set of guiding principles to use in determining the future of the facility – • Sport, leisure and club facilities: maintain and enhance the existing provision and improve social facilities; • History: ensure the historic nature of the site is conserved and made more accessible to the general public; • Architecture: retain the iconic nature of Fort Regent structures; • Private finance: explore opportunities for adding development to current structure in partnership with private sector. -

The Lives of the Saints of His Family

'ii| Ijinllii i i li^«^^ CORNELL UNIVERSITY LIBRARY Cornell University Libraru BR 1710.B25 1898 V.16 Lives of the saints. 3 1924 026 082 689 The original of tliis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924026082689 *- ->^ THE 3Ltt3e0 of ti)e faints REV. S. BARING-GOULD SIXTEEN VOLUMES VOLUME THE SIXTEENTH ^ ^ «- -lj« This Volume contains Two INDICES to the Sixteen Volumes of the work, one an INDEX of the SAINTS whose Lives are given, and the other u. Subject Index. B- -»J( »&- -1^ THE ilttieg of tt)e ^amtsi BY THE REV. S. BARING-GOULD, M.A. New Edition in i6 Volumes Revised with Introduction and Additional Lives of English Martyrs, Cornish and Welsh Saints, and a full Index to the Entire Work ILLUSTRATED BY OVER 400 ENGRAVINGS VOLUME THE SIXTEENTH LONDON JOHN C. NIMMO &- I NEW YORK : LONGMANS, GREEN, CO. MDCCCXCVIII I *- J-i-^*^ ^S^d /I? Printed by Ballantyne, Hanson &' Co. At the Ballantyne Press >i<- -^ CONTENTS The Celtic Church and its Saints . 1-86 Brittany : its Princes and Saints . 87-120 Pedigrees of Saintly Families . 121-158 A Celtic and English Kalendar of Saints Proper to the Welsh, Cornish, Scottish, Irish, Breton, and English People 159-326 Catalogue of the Materials Available for THE Pedigrees of the British Saints 327 Errata 329 Index to Saints whose Lives are Given . 333 Index to Subjects . ... 364 *- -»J< ^- -^ VI Contents LIST OF ADDITIONAL LIVES GIVEN IN THE CELTIC AND ENGLISH KALENDAR S. -

48 St Saviour Q3 2020.Pdf

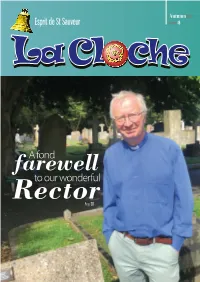

Autumn2020 Esprit de St Sauveur Edition 48 farewellA fond Rectorto our wonderful Page 30 C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Autumn 2020 St Saviour Parish Magazine p3 From the Editor Featured Back on Track! articles La Cloche is back on track and we have a full magazine. There are some poems by local From the Constable poets to celebrate Liberation and some stories from St Saviour residents who were in Jersey when the Liberation forces arrived on that memorable day, 9th May 1945. It is always enlightening to read and hear of others’ stories from the Occupation and Liberation p4 of Jersey during the 1940s. Life was so very different then, from now, and it is difficult for us to imagine what life was really like for the children and adults living at that time. Giles Bois has submitted a most interesting article when St Saviour had to build a guardhouse on the south coast. The Parish was asked to help Grouville with patrolling Liberation Stories the coast looking for marauders and in 1690 both parishes were ordered to build a guardhouse at La Rocque. This article is a very good read and the historians among you will want to rush off to look for our Guardhouse! Photographs accompany the article to p11 illustrate the building in the early years and then later development. St Saviour Battle of Flowers Association is managing to keep itself alive with a picnic in St Paul’s Football Club playing field. They are also making their own paper flowers in different styles and designs; so please get in touch with the Association Secretary to help with Forever St Saviour making flowers for next year’s Battle. -

The Island Identity Policy Development Board Jersey's

The Island Identity Policy Development Board Jersey’s National and International Identity Interim Findings Report 1 Foreword Avant-propos What makes Jersey special and why does that matter? Those simple questions, each leading on to a vast web of intriguing, inspiring and challenging answers, underpin the creation of this report on Jersey’s identity and how it should be understood in today’s world, both in the Island and internationally. The Island Identity Policy Development Board is proposing for consideration a comprehensive programme of ways in which the Island’s distinctive qualities can be recognised afresh, protected and celebrated. It is the board’s belief that success in this aim must start with a much wider, more confident understanding that Jersey’s unique mixture of cultural and constitutional characteristics qualifies it as an Island nation in its own right. An enhanced sense of national identity will have many social and cultural benefits and reinforce Jersey’s remarkable community spirit, while a simultaneously enhanced international identity will protect its economic interests and lead to new opportunities. What does it mean to be Jersey in the 21st century? The complexity involved in providing any kind of answer to this question tells of an Island full of intricacy, nuance and multiplicity. Jersey is bursting with stories to tell. But none of these stories alone can tell us what it means to be Jersey. In light of all this complexity why take the time, at this moment, to investigate the different threads of what it means to be Jersey? I would, at the highest level, like to offer four main reasons: First, there is a profound and almost universally shared sense that what we have in Jersey is special. -

The SAINTS in SACRED SCRIPTURE

International Crusade for Holy Relics P.O. Box 21301 Los Angeles, Ca. 90021 www.ICHRusa.com The SAINTS IN SACRED SCRIPTURE. 2 Chronicles 6:41 - "And now arise, O LORD God, and go to thy resting place, thou and the ark of thy might. Let thy priests, O LORD God, be clothed with salvation, and let thy saints rejoice in thy goodness. Psalms 16:3 - As for the saints in the land, they are the noble, in whom is all my delight. Psalms 30:4 - Sing praises to the LORD, O you his saints, and give thanks to his holy name. Psalms 31:23 - Love the LORD, all you his saints! The LORD preserves the faithful, but abundantly requites him who acts haughtily. Psalms 34:9 - O fear the LORD, you his saints, for those who fear him have no want! Psalms 37:28 - For the LORD loves justice; he will not forsake his saints. The righteous shall be preserved for ever, but the children of the wicked shall be cut off. Psalms 79:2 - They have given the bodies of thy servants to the birds of the air for food, the flesh of thy saints to the beasts of the earth. Psalms 85:8 - Let me hear what God the LORD will speak, for he will speak peace to his people, to his saints, to those who turn to him in their hearts. Psalms 97:10 - The LORD loves those who hate evil; he preserves the lives of his saints; he delivers them from the hand of the wicked.