Inclusive and Special Education Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planning Control Applications

PLANNING CONTROL APPLICATIONS *17305. L-ONOR KEVIN CUTAJAR staqsa lill-Ministru għall-Ambjent, it-Tibdil fil-Klima u l-Ippjanar: Jista' l-Ministru jgħid kemm hemm Planning Control Applications f'kull lokalità f'Malta u f'Għawdex u dan sal-mument li titwieġeb din id-domanda? Jista' jindika wkoll l-iskop ta' kull waħda minn dawn l-applikazzjonijiet? 16/11/2020 ONOR. AARON FARRUGIA: Qed inpoġġi fuq il-Mejda tal-Kamra tabella bid-dettalji mitluba. Seduta Numru 403 23/11/2020 PQ 17305. PC's Pending - Status not in DEC, INV, REC, WDN and WPD and Validation Date is not null 17/11/2020 L.C. Proposal Attard Redesigning Alignment Scheme of 2 corner properties. Attard Proposed shifting of existing building and front garden alignment. Attard Creation of cul-de-sac. Attard proposed shifting of building alignment (no changes to front garden alignment) to match building alignment of adjacent building Birkirkara To reduce splay from 4.57m to 4.09m. Birkirkara To amend existing front garden alignment and extend the existing road, and to limit the provisions of Central Malta Local Plan policy BK06 (CPPS) to the levels below road level. Standard policies for residential areas (CG07) to apply above road level. Birkirkara Proposal to shift part of building alignment Birkirkara Realignment of building alignment, and change of schemed road connecting Triq l-Imdina and Triq l-Inginerija from proposed road to pedestrian only footway path, connecting the industrial area to the main road. Birkirkara Proposed changes to building alignment and proposed public pedestrian open space. Birkirkara Proposed change in Zoning from Industrial Area to Residential Area. -

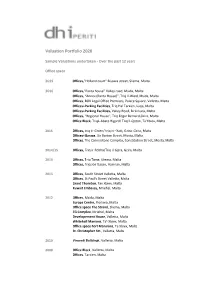

CV Dhi No Client 2020

Valuation Portfolio 2020 Sample Valuations undertaken - Over the past 12 years Office space 2019 Offices, "Holland court" Bisazza street, Sliema, Malta 2016 Offices, "Panta house" Valley road, Msida, Malta Offices, “Annex (Panta House)”, Triq Il-Wied, Msida, Malta Offices , BOV Legal Office Premises, Palace Square, Valletta, Malta Offices+Parking Facilities , Triq Hal Tarxien, Luqa, Malta Offices+Parking Facilities, Valley Road, Birkirkara, Malta Offices, "Regional House", Triq Edgar Bernard,Gzira, Malta Office Block, TriqL-Abate Rigord/ Triq Il-Qoton, Ta'Xbiex, Malta 2015 Offices, triq il- Gnien/ triq ix –Xatt, Gzira. Gzira, Malta Offices+Garage , Sir Borton Street, Mosta, Malta Offices , The Cornerstone Complex, Constitution Street, Mosta, Malta 2014/15 Offices, Triq ir-Rebha/Triq il-Gzira, Gzira, Malta 2014 Offices, T riq Tigne, Sliema, Malta Offices, Triq Joe Gasan, Hamrun, Malta 2013 Offices , South Street Valletta, Malta Offices , St Paul's Street Valletta, Malta Grant Thornton , Tax Xbiex, Malta Kuwait Embassy, Mriehel, Malta 2012 Offices , Msida, Malta Europa Centre , Floriana, Malta Office space The Strand , Sliema, Malta TG Complex , Mriehel, Malta Developement House , Valletta, Malta Whitehall Manions , Ta'-Xbiex, Malta Office space Fort Mansions , Ta Xbiex, Malta St. Christopher Str. , Valletta, Malta 2010 Vincenti Buildings , Valletta, Malta 2008 Office Block , Valletta, Malta Offices , Tarxien, Malta Office Developments 2017 Offices+Garages,(Ex Savoy Hotel Property) Sliema, Malta Old Peoples Homes 2020 Ex Imperial hotel, Sliema, Malta Casa Antonia, Balzan, Malta 2018 H.O.P.H. LTD. Sta. Venera, Malta 2016 ACK. LTD. Property No.4, Msida, Malta 2014 Bugibba Holiday Complex Block C, Bugibba, Malta 2011 Roseville Retirement Complex, Lija, Malta Villa Messsina, Rabat, Malta 2010 Sa Maison, Msida, Malta Hotels 2020 Ape Boutique Accomadation, St Julians hill c/w old college, Sliema. -

Mediterranean Island Flair with English Influence

Escuela-Ref.Ma4 - Msida - Familia y residencia Malta Mediterranean island flair with English influence Nowhere else in Europe will you be better able to both consolidate your English skills and enjoy the Mediterranean sea than in Malta. At Eurocentres Malta, located in the area of Msida with all amenities within reach, students can dive into the island’s culture and the shore-side lifestyle. The school building has a terrace and ensures with its air-conditioned classrooms that you stay cool while studying towards your language goals. The lively cities of Valletta, Sliema and St. Julians – Malta’s nightlife district – are close by and offer further possibilities for exploring Malta’s magic. School - COURSES & EXAMS COURSES & EXAMS 20 Basic General Language 20 Basic General Language 25 Intensive General Language, IELTS, TOEFL 25 Intensive General Language 30 Super Intensive CAE, CPE, FCE, General 30 Super Intensive General Language, IELTS Language, IELTS Cape Town PRICES IN EUR Malta LESSONS PER 20 25 30 8 Classrooms Learning Centre Computer Room Student Lounge 12 Classrooms Learning Centre Computer Room Student Lounge WEEK Library Kitchen Snack machines Air conditioning Free Wi-fi 2 weeks 412 480 550 Library Terrace / Balcony Garden Air conditioning Free Wi-fi 3 weeks 618 720 825 4 weeks 780 920 1,060 5 weeks 975 1,150 1,325 6 weeks 1,170 1,380 1,590 7 weeks 1,365 1,610 1,771 8 weeks 1,464 1,736 2,016 9 weeks 1,647 1,953 2,268 10 weeks 1,830 2,170 2,520 11 weeks 2,013 2,387 2,772 12 weeks 2,088 2,496 2,916 Add. -

Local Councils Within the Central Region Open Water Swimming

Dok A Proposed sports events and the relative expenses to be organized in the local councils within the Central Region Local councils within the Central Region The Central Region includes the following 13 local councils: Attard - include the areas of Ħal Warda, Misraħ Kola, Sant'Anton and Ta' Qali. Balzan Birkirkara - include the areas of Fleur-de-Lys, Swatar, Tal-Qattus, Ta' Paris and Mrieħel. Gżira - include the area of Manoel Island Iklin Lija - include the area of Tal-Mirakli Msida - include the areas of Swatar and Tal-Qroqq Pietà - include the area of Gwardamanġa St. Julian's - include the areas of Paceville, Balluta Bay, St. George's Bay, and Ta' Ġiorni San Ġwann - include the areas of Kappara, Mensija, Misraħ Lewża and Ta' Żwejt. Santa Venera - include parts of Fleur-de-Lys and Mrieħel Sliema - include the areas of Savoy, Tigné, Qui-si-Sana and Fond Għadir Ta' Xbiex Hamlets Fleur-de-Lys Gwardamanġa Kappara Paceville Swatar Open Water Swimming A series of four open water swims will be held in St. Julian’s, Sliema and Msida/Pieta/Ta’Xbiex area in collaboration with the Lifelong Swimming Project of the Ligue Europeenne de Natation under the auspices of the Aquatic Sports Association of Malta. The estimated cost of these four events amounts to Eur 4,400.00. Athletics Two athletics events in the form of road running races will be held in the Birkirkara/Balzan/Attard/Fleur-de-Lys area under the auspices of the Malta Amateur Athletic Association. The estimated cost of these two events amounts to Euro 2,500.00. -

Winter Schedules

ISLA/VALLETTA 1 Monday to Friday Saturday Sunday Route 1 - Schedule Times Route 1 - Schedule Times Route 1 - Schedule Times 05:30-09:30 20 minutes 05:30-20:00 30 minutes 05:30-20:00 30 minutes 09:31-15:30 30 minutes 20:01-23:00 60 minutes 20:01-23:00 60 minutes 15:31-20:30 20 minutes 20:31-23:00 30 minutes BIRGU VENDA/VALLETTA 2 Monday to Friday Saturday Sunday Route 2 - Schedule Times Route 2 - Schedule Times Route 2- Schedule Times 05:15-20:25 20 minutes 05:30-20:30 30 minutes 05:30-20:00Isla/Birgu/Bormla/Valletta 30 minutes 20:26-22:45 60 minutes 20:31-23:00 60 minutes 20:01-23:00 60 minutes KALKARA/VALLETTA 3 Monday to Friday Saturday Sunday Route 3 - Schedule Times Route 3 - Schedule Times Route 3 - Schedule Times 05:30 - 23:00 30 minutes 05:30 - 23:00 30 minutes 05:30Isla/Birgu/Bormla/Valletta - 23:00 30 minutes BIRGU CENTRE/VALLETTA 4 Monday to Friday Saturday Sunday Route 4 - Schedule Times Route 4 - Schedule Times Route 4 - Schedule Times 05:30:00 - 20:30 30 minutes 05:30-20:00 30 minutes 05:30-20:00 30 minutes 20:31 - 23:00 60 minutes 20:01-23:00 60 minutes 20:01-23:00 60 minutes BAHAR IC-CAGHAQ/VALLETTA 13 Monday to Friday Saturday Sunday Route 13 - Schedule Times Route 13 - Schedule Times Route 13 - Schedule Times 05:05 - 20:30 10 minutes 05:05 - 20:30 10 minutes 05:05 - 20:30 10 minutes 20:31 - 23:00 15 minutes 20:31 - 23:00 15 minutes 20:31 - 23:00 15 minutes PEMBROKE/VALLETTA 14 Monday to Friday Saturday Sunday Route 14 - Schedule Times Route 14 - Schedule Times Route 14 - Schedule Times 05:25 - 20:35 20 minutes 05:25 - -

L-4 Ta' Diċembru, 2019

L-4 ta’ Diċembru, 2019 25,349 PROĊESS SĦIĦ FULL PROCESS Applikazzjonijiet għal Żvilupp Sħiħ Full Development Applications Din hija lista sħiħa ta’ applikazzjonijiet li waslu għand This is a list of complete applications received by the l-Awtorità tal-Ippjanar. L-applikazzjonijiet huma mqassmin Planning Authority. The applications are set out by locality. bil-lokalità. Rappreżentazzjonijiet fuq dawn l-applikazzjonijiet Any representations on these applications should be sent in għandhom isiru bil-miktub u jintbagħtu fl-uffiċini tal-Awtorità writing and received at the Planning Authority offices or tal-Ippjanar jew fl-indirizz elettroniku ([email protected]. through e-mail address ([email protected]) within mt) fil-perjodu ta’ żmien speċifikat hawn taħt, u għandu the period specified below, quoting the reference number. jiġi kkwotat in-numru ta’ referenza. Rappreżentazzjonijiet Representations may also be submitted anonymously. jistgħu jkunu sottomessi anonimament. Is-sottomissjonijiet kollha lill-Awtorità tal-Ippjanar, All submissions to the Planning Authority, submitted sottomessi fiż-żmien speċifikat, jiġu kkunsidrati u magħmula within the specified period, will be taken into consideration pubbliċi. and will be made public. L-avviżi li ġejjin qed jiġu ppubblikati skont Regolamenti The following notices are being published in accordance 6(1), 11(1), 11(2)(a) u 11(3) tar-Regolamenti dwar l-Ippjanar with Regulations 6(1), 11(1), 11(2)(a), and 11(3) of the tal-Iżvilupp, 2016 (Proċedura ta’ Applikazzjonijiet u Development Planning (Procedure for Applications and d-Deċiżjoni Relattiva) (A.L.162 tal-2016). their Determination) Regulations, 2016 (L.N.162 of 2016). Rappreżentazzjonijiet fuq l-applikazzjonijiet li ġejjin Any representations on the following applications should għandhom isiru sat-13 ta’ Jannar, 2020. -

Annual Report 2017 Contents

ANNUAL REPORT 2017 CONTENTS 3 4 9 CEO Water Water Report Resources Quality 14 20 32 Compliance Network Corporate Infrastructure Services Directorate 38 45 48 Strategic Human Unaudited Information Resources Financial Directorate Statement 2017 ANNUAL REPORT CEO REPORT CEO Report 2017 was a busy year for the Water Services quality across Malta. Secondly, RO plants will be Corporation, during which it worked hard to become upgraded to further improve energy efficiency and more efficient without compromising the high quality production capacity. Furthermore, a new RO plant service we offer our customers. will be commissioned in Gozo. This RO will ensure self-sufficiency in water production for the whole During a year, in which the Corporation celebrated island of Gozo. The potable water supply network to its 25th anniversary, it proudly inaugurated the North remote areas near Siġġiewi, Qrendi and Haż-Żebbuġ Wastewater Treatment Polishing Plant in Mellieħa. will be extended. Moreover, ground water galleries This is allowing farmers in the Northern region to will also be upgraded to prevent saline intrusion. benefit from highly polished water, also known as The project also includes the extension of the sewer ‘New Water’. network to remote areas that are currently not WSC also had the opportunity to establish a number connected to the network. Areas with performance of key performance indicator dashboards, produced issues will also be addressed. inhouse, to ensure guaranteed improvement. These Having only been recently appointed to lead the dashboards allow the Corporation to be more Water Services Corporation, I fully recognize that the efficient, both in terms of performance as well as privileges of running Malta’s water company come customer service. -

Summer Schedules

ISLA/VALLETTA 1 Monday to Friday Saturday Sunday Route 1 - Schedule Times Route 1 - Schedule Times Route 1 - Schedule Times 05:30-09:30 20 minutes 05:30-22:30 30 minutes 05:30-22:30 30 minutes 09:31-11:29 30 minutes 11:30-16:30 20 minutes 16:31-23:00 30 minutes BIRGU VENDA/VALLETTA 2 Monday to Friday Saturday Sunday Route 2 - Schedule Times Route 2 - Schedule Times Route 2- Schedule Times 05:15-20:25 20 minutes 05:30:00-22:45 30 minutes 05:30:00-22:45Isla/Birgu/Bormla/Valletta30 minutes 20:26-22:45 60 minutes KALKARA/VALLETTA 3 Monday to Friday Saturday Sunday Route 3 - Schedule Times Route 3 - Schedule Times Route 3 - Schedule Times 05:30 - 23:00 30 minutes 05:30 - 23:00 30 minutes 05:30Isla/Birgu/Bormla/Valletta - 23:00 30 minutes BIRGU CENTRE/VALLETTA 4 Monday to Friday Saturday Sunday Route 4 - Schedule Times Route 4 - Schedule Times Route 4 - Schedule Times 05:30:00 - 20:30 30 minutes 05:30-20:00 30 minutes 05:30-20:00 30 minutes 20:31 - 23:00 60 minutes 20:01-23:00 60 minutes 20:01-23:00 60 minutes BAHAR IC-CAGHAQ/VALLETTA 13 Monday to Friday Saturday Sunday Route 13 - Schedule Times Route 13 - Schedule Times Route 13 - Schedule Times 05:05 - 20:30 10 minutes 05:05 - 20:30 10 minutes 05:05 - 20:30 10 minutes 20:31 - 23:00 15 minutes 20:31 - 23:00 15 minutes 20:31 - 23:00 15 minutes PEMBROKE/VALLETTA 14 Monday to Friday Saturday Sunday Route 14 - Schedule Times Route 14 - Schedule Times Route 14 - Schedule Times 05:25 - 20:35 20 minutes 05:25 - 20:35 20 minutes 05:25 - 20:35 20 minutes 20:36 -22:48 30 minutes 20:36 -22:48 30 minutes -

Is-26 Ta' Mejju, 2021 5221 This Is a List of Complete Applications

Is-26 ta’ Mejju, 2021 5221 PROĊESS SĦIĦ FULL PROCESS Applikazzjonijiet għal Żvilupp Sħiħ Full Development Applications Din hija lista sħiħa ta’ applikazzjonijiet li waslu għand This is a list of complete applications received by the l-Awtorità tal-Ippjanar. L-applikazzjonijiet huma mqassmin Planning Authority. The applications are set out by locality. bil-lokalità. Rappreżentazzjonijiet fuq dawn l-applikazzjonijiet Any representations on these applications should be sent in għandhom isiru bil-miktub u jintbagħtu fl-uffiċini tal-Awtorità writing and received at the Planning Authority offices or tal-Ippjanar jew fl-indirizz elettroniku ([email protected]. through e-mail address ([email protected]) within mt) fil-perjodu ta’ żmien speċifikat hawn taħt, u għandu the period specified below, quoting the reference number. jiġi kkwotat in-numru ta’ referenza. Rappreżentazzjonijiet Representations may also be submitted anonymously. jistgħu jkunu sottomessi anonimament. Is-sottomissjonijiet kollha lill-Awtorità tal-Ippjanar, All submissions to the Planning Authority, submitted sottomessi fiż-żmien speċifikat, jiġu kkunsidrati u magħmula within the specified period, will be taken into consideration pubbliċi. and will be made public. L-avviżi li ġejjin qed jiġu ppubblikati skont Regolamenti The following notices are being published in accordance 6(1), 11(1), 11(2)(a) u 11(3) tar-Regolamenti dwar l-Ippjanar with Regulations 6(1), 11(1), 11(2)(a), and 11(3) of the tal-Iżvilupp, 2016 (Proċedura ta’ Applikazzjonijiet u Development Planning (Procedure for Applications and d-Deċiżjoni Relattiva) (A.L.162 tal-2016). their Determination) Regulations, 2016 (L.N.162 of 2016). Rappreżentazzjonijiet fuq l-applikazzjonijiet li ġejjin Any representations on the following applications should għandhom isiru sal-25 ta’ Ġunju, 2021. -

Petition Booklet

Referenda Act : Declaration for the holding of a Referendum We the undersigned persons, being registered as voters for the election of members of the House of Representatives, demand that the question whether the following provision of law, that is to say Framework for Allowing a Derogation Opening a Spring Hunting Season for Turtledove and Quail Regulations (Subsidiary Legislation 504.94 - Legal Notice 221 of 2010) should not continue in force, shall be put to those entitled to vote in a referendum under Part V of the Referendum Act. Electoral Name and Surname Signature ID Card Address (in full) Division Please return to 57/28 Triq Abate Rigord, Ta’ Xbiex XBX 1120 What spring hunting takes place in Malta? In view of the consistent lack of action by government and Dear Members, inertia on the European Commission’s part, the Coalition To hunt birds in spring, hunters apply for a license that allows believes it is time for the people to have their say through a them to shoot quails (summien) and turtle doves (gamiem) referendum to remove the law that allows hunting in spring. Thirteen Maltese organisations have decided to work for two weeks in April. Last spring about 9500 hunters were together to bring an end to spring hunting in Malta. licensed to shoot up to 11,000 turtle doves and 5000 quail Isn’t it unfair to deprive hunters of their hobby? The task of the Coalition for the Abolition of among themselves. The licence (previously €50) is free of Spring Hunting is to gather at least 34,000 signatures charge, and hunters are asked to report what they catch by Maltese bird hunters already have months in autumn and to petition the government to hold a referendum to sending an SMS to the relevant authority. -

Gazzetta Tal-Gvern Ta' Malta

Nru./No. 20,408 Prezz/Price €1.98 Gazzetta tal-Gvern ta’ Malta The Malta Government Gazette L-Erbgħa, 20 ta’ Mejju, 2020 Pubblikata b’Awtorità Wednesday, 20th May, 2020 Published by Authority SOMMARJU — SUMMARY Avviżi tal-Awtorità tal-Ippjanar ....................................................................................... 4025 - 4064 Planning Authority Notices .............................................................................................. 4025 - 4064 L-20 ta’ Mejju, 2020 4025 PROĊESS SĦIĦ FULL PROCESS Applikazzjonijiet għal Żvilupp Sħiħ Full Development Applications Din hija lista sħiħa ta’ applikazzjonijiet li waslu għand This is a list of complete applications received by the l-Awtorità tal-Ippjanar. L-applikazzjonijiet huma mqassmin Planning Authority. The applications are set out by locality. bil-lokalità. Rappreżentazzjonijiet fuq dawn l-applikazzjonijiet Any representations on these applications should be sent in għandhom isiru bil-miktub u jintbagħtu fl-uffiċini tal-Awtorità writing and received at the Planning Authority offices or tal-Ippjanar jew fl-indirizz elettroniku ([email protected]. through e-mail address ([email protected]) within mt) fil-perjodu ta’ żmien speċifikat hawn taħt, u għandu the period specified below, quoting the reference number. jiġi kkwotat in-numru ta’ referenza. Rappreżentazzjonijiet Representations may also be submitted anonymously. jistgħu jkunu sottomessi anonimament. Is-sottomissjonijiet kollha lill-Awtorità tal-Ippjanar, All submissions to the Planning Authority, -

Of the Central Region of Malta a TASTE of the HISTORY, CULTURE and ENVIRONMENT

A TASTE OF THE HISTORY, CULTURE AND ENVIRONMENT of the Central Region of Malta A TASTE OF THE HISTORY, CULTURE AND ENVIRONMENT of the Central Region of Malta Design and layout by Kite Group www.kitegroup.com.mt [email protected] George Cassar First published in Malta in 2019 Publication Copyright © Kite Group Literary Copyright © George Cassar Photography Joseph Galea Printed by Print It, Malta No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the author and the publisher. ISBN: 978-99957-50-67-1 (hardback) 978-99957-50-68-8 (paperback) THE CENTRAL REGION The Central Region is one of five administrative regions in the Maltese Islands. It includes thirteen localities – Ħ’Attard, Ħal Balzan Birkirkara, il-Gżira, l-Iklin, Ħal Lija, l-Imsida, Tal- Pietà, San Ġwann, Tas-Sliema, San Ġiljan, Santa Venera, and Ta’ Xbiex. The Region has an area of about 25km2 and a populations of about 130,574 (2017) which constitutes 28.36 percent of the population of the country. This population occupies about 8 percent of the whole area of the Maltese Islands which means that the density is of around 6,635 persons per km2. The coat-of-arms of the Central Region was granted in 2014 (L.N. 364 of 2014). The shield has a blue field signifying the Mediterranean Sea in which there are thirteen bezants or golden disks representing the thirteen municipalities forming the Region. The blazon is Azure thirteen bezants 3, 3, 3, 3 and 1, all ensigned by a mural coronet of five eschaugettes and a sally port Or.