Long-Term Housing Rentals in Malta: a Look at Advertised Listings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planning Control Applications

PLANNING CONTROL APPLICATIONS *17305. L-ONOR KEVIN CUTAJAR staqsa lill-Ministru għall-Ambjent, it-Tibdil fil-Klima u l-Ippjanar: Jista' l-Ministru jgħid kemm hemm Planning Control Applications f'kull lokalità f'Malta u f'Għawdex u dan sal-mument li titwieġeb din id-domanda? Jista' jindika wkoll l-iskop ta' kull waħda minn dawn l-applikazzjonijiet? 16/11/2020 ONOR. AARON FARRUGIA: Qed inpoġġi fuq il-Mejda tal-Kamra tabella bid-dettalji mitluba. Seduta Numru 403 23/11/2020 PQ 17305. PC's Pending - Status not in DEC, INV, REC, WDN and WPD and Validation Date is not null 17/11/2020 L.C. Proposal Attard Redesigning Alignment Scheme of 2 corner properties. Attard Proposed shifting of existing building and front garden alignment. Attard Creation of cul-de-sac. Attard proposed shifting of building alignment (no changes to front garden alignment) to match building alignment of adjacent building Birkirkara To reduce splay from 4.57m to 4.09m. Birkirkara To amend existing front garden alignment and extend the existing road, and to limit the provisions of Central Malta Local Plan policy BK06 (CPPS) to the levels below road level. Standard policies for residential areas (CG07) to apply above road level. Birkirkara Proposal to shift part of building alignment Birkirkara Realignment of building alignment, and change of schemed road connecting Triq l-Imdina and Triq l-Inginerija from proposed road to pedestrian only footway path, connecting the industrial area to the main road. Birkirkara Proposed changes to building alignment and proposed public pedestrian open space. Birkirkara Proposed change in Zoning from Industrial Area to Residential Area. -

Name of Authority Name of Regulated Professions Name of Contact Person Telephone Number Email Address URL Link Location Address

Name of Authority Name of Regulated Professions Name of Contact Person Telephone Number Email Address URL Link Location Address [email protected], Accountancy Board Accountant, Auditor Martin Spiteri +356 2599 8456 https://accountancyboard.gov.mt/ South Street, VLT 2000 Valletta [email protected] https://kamratalperiti.org/profession/how-to-obtain- Blk B, Triq Francesco Buonamici, Board of Architects' Warrant Architects (Acquired rights), Architect Ryan Sciberras +356 2292 7444 [email protected] the-warrant-of-perit/ Beltissebh, Floriana Board of the Psychotherapy Board of the Psychotherapy Registered Psychotherapist Charles Cassar +356 7949 4456 [email protected] https://family.gov.mt/ppb/Pages/default.aspx Profession, Republic Street, Profession Valletta 173, Triq San Kristofru, Board of Warrant of Restorers Conservator, Restorer Michael Mifsud +356 2395 0000 [email protected] https://www.cultureheritage.gov.mt Valletta, VLT2000, Malta Building Regulation Office Horn Works Ditch Building Regulation Office Energy Performance of Building Assessor Michael Ferry +356 2292 7595 [email protected] https://bca.org.mt/ Emvin Cremona Street Floriana FRN 1280 Chamber of Advocates and Justice Courts of Justice, Second Floor, Lawyer, Solicitor Mark Said +356 2124 8601 [email protected] https://www.avukati.org/ Department Republic Street, Valletta Private Guard, Private Specialized Guard (Not Police General Head Quarters, Driving), Private Specialized Guard (Driving), Police Licences Office Commissioner of Police -

Licensed ELT Schools in Malta and Gozo

LONDON SCHOOL OF COMMERCE (LSC) SEAL MALTA 3rd Floor, Europa Centre 58, Tower Tinghi Street St.Anne Street Xewkija, Gozo Floriana FRN 9020 Tel: (+356) 2156 1909, 9905 7027 MISSION STATEMENT Tel: (+356) 2122 6200 Email: [email protected] The mission of the ELT Council is to foster development in the ELT Email: [email protected] Web: www.sealmalta.com profession and sector. Malta can boast that both its ELT profession and Web: www.lscmalta.edu.mt sector are well structured and closely monitored, being practically the only language-learning destination in the world with legislation that SPRACHCAFFE LANGUAGES PLUS assures that every licensed school maintains a national quality standard. MAGISTER ACADEMY 6, Alamein Road All this has resulted in rapid growth for the sector. L-Arkati, Pembroke PBK 1776 Mensija Street Tel: (+356) 2137 3574/5/6 St. Julians STJ 1960 Email: [email protected] ELT SCHOOLS Malta Web: www.sprachcaffe.com Tel: (+356) 2750 5550 There are currently 38 licensed ELT Schools in Malta and Gozo. Email: [email protected] Web: www.magisteracademy.com STS STUDENT TRAVEL SCHOOLS 67, Old Railway Road Birkirkara BKR 1615 WHY STUDY IN MALTA MALTA UNIVERSITY LANGUAGE Tel: (+356) 2720 1277 SCHOOL Email: [email protected] Combined with its cultural, historical and linguistic heritage, Malta offers University Residence Web: www.sts-education.com a pleasant and congenial climate, a safe and friendly environment, a high R. Mifsud Bonnici Street standard of living, and an excellent quality of life. All this makes it an ideal Lija place where to live and study English. -

ESE Accommodation Options ESE Accommodation Options

ESE Accommodation Options 2017 ESE Residence ESE Building Paceville Avenue, St. Julians STJ 3103 Tel: +356 21373789 Residence inin----househouse ESE main school building ESE Residence Amenities near by: • Bus stops • Post Office • Pharmacy • Supermarkets • Bars • Restaurants • Banks/ATM • Beaches (Rocky) • Paceville Type of accommodation : ESE Residence Other information: Local Transport Age of students: 18 years and over Towels are changed twice a week Bus stops are less than 5 mins from the Residence. 2-hour ticket costs € € Check-in any day after: 15:00 Linen changed weekly 2.00 in summer & 1.50 in winter. For more details visit: www.publictransport.com.mt Check-out any day before: 11:00 Daily maid service Travel time to school: Residence is in school building Fast Facts Available: Year round Breakfast included: Served at ‘The Cake Box’ cafeteria Number of rooms: 19 (*1 wheelchair access) in the school building Number of beds per room: 2 Reception: 24/7 (school reception) Room Types: Single & Twin Key Card (given on arrival) (Hotel rules apply when booking) Deposits and Damages Charges: Refundable deposit Each room is equipped with: of €100 on arrival, (if no damages or fines) Single or Double bed En-suite bathroom Visitors: Visitors are allowed only in reception. Television No visitors are allowed in bedrooms. Free WiFi Noise and Restrictions: Noise must be kept to a Fully air-conditioned minimum after 23:00 ESE White House Hostel White House Hostel Paceville Avenue, St. Julians STJ 3103 Tel: +356 21373789 Opposite ESE school Amenities near by: White House Hostel • Bus stops • Post Office • Pharmacy • Supermarkets • Bars • Restaurants • Banks/ATM • Beaches (Rocky) • Paceville Type of accommodation : ESE Residence Other information: Local Transport Age of students: 18 years and over Bus stops are less than 5 mins from the Residence. -

Summer Schools 2017

SUMMER SCHOOLS 2017 Summer School Name Address 1 Address 2 Locality E-mail 1 BeeSmart Summer Club BeeSmart Triq il-Palazz L-Aħmar Santa Venera [email protected] 2 BeeSmart Summer Club Thi Lakin Thi Lakin Żebbug Road Attard [email protected] 3 CHS Summer School Chiswick House School 38, Antonio Schembri Steet Kappara [email protected] 4 Creative Energy Summer Club St Clare College Pembroke Secondary Suffolk Road Pembroke [email protected] 5 Discover Your Voice Gozo College Middle School Triq Fortunata Mizzi Victoria Gozo [email protected] 6 Eden Summer Camp Eden Leisure St Georges Bay St Julians [email protected] 7 Energize Summer School Energize Summer School Triq ix-Xatt St Julians [email protected] 8 Fantasy Island Club Malta Ta' Warda 95 Triq il-Kbira Żebbuġ [email protected] 9 Gymstars Go Active Summer Club Malta Basketball Association Basketball Pavilion Ta' Qali [email protected] 10 HiKids Il-Liceo Triq Wenzu Mallia Hamrun [email protected] 11 HiKids BLB 802 Bulebel Industrial Estate Żejtun [email protected] 12 Il-Passju JobsPlus Head Office B'Buġia Road Ħal Far [email protected] 13 Kamaja Outdoors St Nicholas Gollege Triq San David Mtarfa [email protected] 14 Kids on Campus University Campus University of Malta Msida [email protected] 15 L.E. Montessori System Summer School Nashville Triq tal-Qattus Birkirkara [email protected] 16 Learn and Play Summer Kids Club Maria Regina College Mosta Primary Grognet Street Mosta [email protected] -

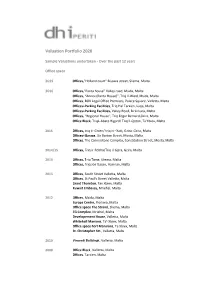

CV Dhi No Client 2020

Valuation Portfolio 2020 Sample Valuations undertaken - Over the past 12 years Office space 2019 Offices, "Holland court" Bisazza street, Sliema, Malta 2016 Offices, "Panta house" Valley road, Msida, Malta Offices, “Annex (Panta House)”, Triq Il-Wied, Msida, Malta Offices , BOV Legal Office Premises, Palace Square, Valletta, Malta Offices+Parking Facilities , Triq Hal Tarxien, Luqa, Malta Offices+Parking Facilities, Valley Road, Birkirkara, Malta Offices, "Regional House", Triq Edgar Bernard,Gzira, Malta Office Block, TriqL-Abate Rigord/ Triq Il-Qoton, Ta'Xbiex, Malta 2015 Offices, triq il- Gnien/ triq ix –Xatt, Gzira. Gzira, Malta Offices+Garage , Sir Borton Street, Mosta, Malta Offices , The Cornerstone Complex, Constitution Street, Mosta, Malta 2014/15 Offices, Triq ir-Rebha/Triq il-Gzira, Gzira, Malta 2014 Offices, T riq Tigne, Sliema, Malta Offices, Triq Joe Gasan, Hamrun, Malta 2013 Offices , South Street Valletta, Malta Offices , St Paul's Street Valletta, Malta Grant Thornton , Tax Xbiex, Malta Kuwait Embassy, Mriehel, Malta 2012 Offices , Msida, Malta Europa Centre , Floriana, Malta Office space The Strand , Sliema, Malta TG Complex , Mriehel, Malta Developement House , Valletta, Malta Whitehall Manions , Ta'-Xbiex, Malta Office space Fort Mansions , Ta Xbiex, Malta St. Christopher Str. , Valletta, Malta 2010 Vincenti Buildings , Valletta, Malta 2008 Office Block , Valletta, Malta Offices , Tarxien, Malta Office Developments 2017 Offices+Garages,(Ex Savoy Hotel Property) Sliema, Malta Old Peoples Homes 2020 Ex Imperial hotel, Sliema, Malta Casa Antonia, Balzan, Malta 2018 H.O.P.H. LTD. Sta. Venera, Malta 2016 ACK. LTD. Property No.4, Msida, Malta 2014 Bugibba Holiday Complex Block C, Bugibba, Malta 2011 Roseville Retirement Complex, Lija, Malta Villa Messsina, Rabat, Malta 2010 Sa Maison, Msida, Malta Hotels 2020 Ape Boutique Accomadation, St Julians hill c/w old college, Sliema. -

Rise and Fall of the Malta Railway After

40 I FEBRUARY 28, 2021 THE SUNDAY TIMES OF MALTA THE SUNDAY TIMES OF MALTA FEBRUARY 28, 2021 I 41 LIFEANDWELLBEING HISTORY Map of the route of It hap~ened in February the Malta Railway /Via/ta Rise and fall Of the VALLETTA Malta Railway after • • • Employees of the Malta Railway pose for a group photograph at its ~naugurat1ons f'famrun Station in 1924. Bombes) on to Hamrun Sta the Attard-Mdina road through Because of debts, calculated to have been in the region of THE MALTA RAILWAY CO. LTD. .in 1883' and 1892 tion. At Hamrun, there was a a 25-yard-long tunnel and then double track w.ith two plat up the final steep climb to £80,000, the line closed down LOCOMOTIVES - SOME TECHNICAL DATA servic.e in Valletta. Plans were The Malta Railways Co. Ltd in forms and side lines leading to Rabat which was the last termi on Tuesday, April 1, 1890, but JOSEPH F. submitted by J. Scott Tucker in augurated its service at 3pm on the workshops which, by 1900, nus till 1900. In that year, the government reopened it on GRIMA 1870, Major Hutchinson in Wednesday, February 28, 1883, were capable of major mainte line was extended via a half Thursday, February 25, 1892. No. Type CyUnders Onches) Builder Worlm No. Data 1873, Architect Edward Rosen amid great enthusiasm. That af nance and engineering work. mile tunnel beneath Mdina to During the closure period, 1. 0-6-0T, 10Yz x 18, Manning Wardle 842, 1882 Retired casual bush in 1873 and George Fer ternoon, the guests were taken Formerly, repairs and renova the Museum Station just below works on buildings were car 2. -

MALTA | Sliema

MALTA | Sliema Malta Sliema is the popular, upmarket seaside town in central Malta. The area is full of shops, restaurants, bars and leisure places. Public transport links to the capital city, Valletta, and other heritage sites and areas. St Julian’s, a popular nightlife area, is only 15 minutes away. Gozo Ghajnsielem Mgarr Mediterranean Harbour Sea Cirkewwa 10km 20km Sliema 30km St. Julian’s Gzira Mdina Valletta Victoria Malta Luqa Airport Sliema’s promenade is one Valletta is the capital of Fortified towns have a of the most popular social Malta and a World Heritage charm and character that meeting places in Malta. site. It is a monument of distinguish them from other Transport links towns. The Three Cities were Baroque architecture built > MLA 20 minutes by the Knights of St John home to the Knights of five centuries ago. Malta. Sliema to Luqa Airport 20 min by taxi From Sliema By Bus 20 minutes to the capital, Valletta 10 minutes to the entertainment and night-life area of St Julians 30 minutes to medieval Mdina 40 minutes to Golden Bay sandy beach 1 hour to Cirkewwa for ferries to Gozo 2-hour ticket €2.00, 7-day ticket €21.00. For more details please visit www.publictransport.com.mt visitmalta.com visitmalta.com visitmalta.com Mdina is a “must see” for Do not miss out on mouth- Maltese Fishing villages are School to Days Inn Hotel every individual visiting watering cuisine with a kaleidoscope of colours. & Residence Maltese Islands. The city is influences from previous Traditional fishing boats 5 minutes on foot. -

Mediterranean Island Flair with English Influence

Escuela-Ref.Ma4 - Msida - Familia y residencia Malta Mediterranean island flair with English influence Nowhere else in Europe will you be better able to both consolidate your English skills and enjoy the Mediterranean sea than in Malta. At Eurocentres Malta, located in the area of Msida with all amenities within reach, students can dive into the island’s culture and the shore-side lifestyle. The school building has a terrace and ensures with its air-conditioned classrooms that you stay cool while studying towards your language goals. The lively cities of Valletta, Sliema and St. Julians – Malta’s nightlife district – are close by and offer further possibilities for exploring Malta’s magic. School - COURSES & EXAMS COURSES & EXAMS 20 Basic General Language 20 Basic General Language 25 Intensive General Language, IELTS, TOEFL 25 Intensive General Language 30 Super Intensive CAE, CPE, FCE, General 30 Super Intensive General Language, IELTS Language, IELTS Cape Town PRICES IN EUR Malta LESSONS PER 20 25 30 8 Classrooms Learning Centre Computer Room Student Lounge 12 Classrooms Learning Centre Computer Room Student Lounge WEEK Library Kitchen Snack machines Air conditioning Free Wi-fi 2 weeks 412 480 550 Library Terrace / Balcony Garden Air conditioning Free Wi-fi 3 weeks 618 720 825 4 weeks 780 920 1,060 5 weeks 975 1,150 1,325 6 weeks 1,170 1,380 1,590 7 weeks 1,365 1,610 1,771 8 weeks 1,464 1,736 2,016 9 weeks 1,647 1,953 2,268 10 weeks 1,830 2,170 2,520 11 weeks 2,013 2,387 2,772 12 weeks 2,088 2,496 2,916 Add. -

Inclusive and Special Education Review

INCLUSIVE AND SPECIAL EDUCATION REVIEW Lino Spiteri George Borg Anne Marie Callus Joseph Cauchi Micheline Sciberras June, 2005 INCLUSIVE AND SPECIAL EDUCATION REVIEW INCLUSIVE AND SPECIAL EDUCATION: REVIEW REPORT June 2005 Ministry of Education, Youth and Employment, Floriana, Malta Tel: (+356) 21231374/5 Fax: (+356) 21242759 E-mail: [email protected] Url: www.education.gov.mt www.education.gov.mt/inclusion.htm © Ministry of Education, Youth and Employment 2004 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior permission in writing of the author, and of the publisher, which must be obtained beforehand. Published by: Ministry of Education, Youth and Employment ISBN 99909-74-21-7 Author: Inclusive and Special Education Review Working Group Publication: Ministry of Education, Youth and Employment Designed & Printed by Salesian Press INCLUSIVE AND SPECIAL EDUCATION REVIEW Inclusive and Special Education Review Working Group 31st May 2005 Hon. Dr Louis Galea, B.A., LL.D., MP Minister of Education, Youth and Employment Ministry of Education, Youth and Employment Floriana, CMR 02 Dear Minister, Review of Inclusive and Special Education We enclose herewith a Report following a review of Inclusive and Special Education we have carried out, in accordance with your letter and terms of reference of 2nd December 2004. The Working Group are available to meet with you to discuss this Report, at your convenience. We wish to thank all those who made their views known to us, and who helped us to progress with our deliberations. -

Gazzetta Tal-Gvern Ta' Malta

Nru./No. 20,503 Prezz/Price €2.52 Gazzetta tal-Gvern ta’ Malta The Malta Government Gazette L-Erbgħa, 21 ta’ Ottubru, 2020 Pubblikata b’Awtorità Wednesday, 21st October, 2020 Published by Authority SOMMARJU — SUMMARY Avviżi tal-Awtorità tal-Ippjanar ....................................................................................... 9457 - 9508 Planning Authority Notices .............................................................................................. 9457 - 9508 Il-21 ta’ Ottubru, 2020 9457 PROĊESS SĦIĦ FULL PROCESS Applikazzjonijiet għal Żvilupp Sħiħ Full Development Applications Din hija lista sħiħa ta’ applikazzjonijiet li waslu għand This is a list of complete applications received by the l-Awtorità tal-Ippjanar. L-applikazzjonijiet huma mqassmin Planning Authority. The applications are set out by locality. bil-lokalità. Rappreżentazzjonijiet fuq dawn l-applikazzjonijiet Any representations on these applications should be sent għandhom isiru bil-miktub u jintbagħtu fl-uffiċini tal-Awtorità in writing and received at the Planning Authority offices or tal-Ippjanar jew fl-indirizz elettroniku ([email protected]. through e-mail address ([email protected]) within mt) fil-perjodu ta’ żmien speċifikat hawn taħt, u għandu the period specified below, quoting the reference number. jiġi kkwotat in-numru ta’ referenza. Rappreżentazzjonijiet Representations may also be submitted anonymously. jistgħu jkunu sottomessi anonimament. Is-sottomissjonijiet kollha lill-Awtorità tal-Ippjanar, All submissions to the Planning -

Module 1 Gozo Today

Unit 1 - Gozo Today Josianne Vella Preamble: This first unit brings a brief overview of the Island’s physical and human geography, including a brief historic overview of the economic activities in Gozo. Various means of access to, and across the island as well as some of the major places of interest have been interspersed with information on the Island’s customs and unique language. ‘For over 5,000 years people have lived here, and have changed and shaped the land, the wild plants and animals, the crops and the constructions and buildings on it. All that speaks of the past and the traditions of the Islands, of the natural world too, is heritage.’ Haslam, S. M. & Borg, J., 2002. ‘Let’s Go and Look After our Nature, our Heritage!’. Ministry of Agriculture & Fisheries - Socjeta Agraria, Malta. The Island of Gozo Location: Gozo (Għawdex) is the second largest island of the Maltese Archipelago. The archipelago consists of the Islands of Malta, Gozo and Comino as well as a few other uninhabited islets. It is roughly situated in the middle of the Mediterranean Sea, about 93km south of Sicily, 350 kilometres due north of Tripoli and about 290 km from the nearest point on the North African mainland. Size: The total surface area of the Islands amounts to 315.6 square kilometres and are among the smallest inhabited islands in the Mediterranean. With a coastline of 47 km, Gozo occupies an area of 66 square kilometres and is 14 km at its longest and 7 km at its widest. IRMCo, Malta e-Module Gozo Unit 1 Page 1/8 Climate: The prevailing climate in the Maltese Islands is typically Mediterranean, with a mild, wet winter and a long, dry summer.