Read the Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Alias Walter Lam Or Lam San Ping). A-5366278, Yokoya, Yoshi Or Sei Cho Or Shiqu Ono Or Yoshi Mori Or Toshi Toyoshima

B44 CONCURRENT RESOLUTIONS—MAY 23, 1951 [65 STAT. A-3726892, Yau, Lam Chai or Walter Lum or Lum Chai You (alias Walter Lam or Lam San Ping). A-5366278, Yokoya, Yoshi or Sei Cho or Shiqu Ono or Yoshi Mori or Toshi Toyoshima. A-7203890, Young, Choy Shie or Choy Sie Young or Choy Yong. A-96:87179, Yuen, Wong or Wong Yun. A-1344004, Yunger, Anna Steibel or Anna Kirch (inaiden name). A-2383005, Zainudin, Yousuf or Esouf Jainodin or Eusoof Jainoo. A-5819992, Zamparo, Frank or Francesco Zamparo. A-5292396, Zanicos, Kyriakos. A-2795128, Zolas, Astghik formerly Boyadjian (nee Hatabian). A-7011519, Zolas, Edward. A-7011518, Zolas, Astghik Fimi. A-4043587, Zorrilla, Jesus Aparicio or Jesus Ziorilla or Zorrilla. A-7598245, Mora y Gonzales, Isidoro Felipe de. Agreed to May 23, 1951. May 23, 1951 [S. Con. Res. 10] DEPORTATION SUSPENSIONS Resolved hy the Senate (the House of Representatives concurrmgr), That the Congress favors the suspension of deportation in the case of each alien hereinafter named, in which case the Attorney General has suspended deportation for more than six months: A-2045097, Abalo, Gelestino or George Abalo or Celestine Aballe. A-5706398, Ackerman, 2Jelda (nee Schneider). A-4158878, Agaccio, Edmondo Giuseppe or Edmondo Joseph Agaccio or Joe Agaccio or Edmondo Ogaccio. A-5310181, Akiyama, Sumiyuki or Stanley Akiyama. A-7112346, Allen, Arthur Albert (alias Albert Allen). A-6719955, Almaz, Paul Salin. A-3311107, Alves, Jose Lino. A-4736061, Anagnostidis, Constantin Emanuel or Gustav or Con- stantin Emannel or Constantin Emanuel Efstratiadis or Lorenz Melerand or Milerand. A-744135, Angelaras, Dimetrios. -

Retweeting Through the Great Firewall a Persistent and Undeterred Threat Actor

Retweeting through the great firewall A persistent and undeterred threat actor Dr Jake Wallis, Tom Uren, Elise Thomas, Albert Zhang, Dr Samantha Hoffman, Lin Li, Alex Pascoe and Danielle Cave Policy Brief Report No. 33/2020 About the authors Dr Jacob Wallis is a Senior Analyst working with the International Cyber Policy Centre. Tom Uren is a Senior Analyst working with the International Cyber Policy Centre. Elise Thomas is a Researcher working with the International Cyber Policy Centre. Albert Zhang is a Research Intern working with the International Cyber Policy Centre. Dr Samanthan Hoffman is an Analyst working with the International Cyber Policy Centre. Lin Li is a Researcher working with the International Cyber Policy Centre. Alex Pascoe is a Research Intern working with the International Cyber Policy Centre. Danielle Cave is Deputy Director of the International Cyber Policy Centre. Acknowledgements ASPI would like to thank Twitter for advanced access to the takedown dataset that formed a significant component of this investigation. The authors would also like to thank ASPI colleagues who worked on this report. What is ASPI? The Australian Strategic Policy Institute was formed in 2001 as an independent, non‑partisan think tank. Its core aim is to provide the Australian Government with fresh ideas on Australia’s defence, security and strategic policy choices. ASPI is responsible for informing the public on a range of strategic issues, generating new thinking for government and harnessing strategic thinking internationally. ASPI International Cyber Policy Centre ASPI’s International Cyber Policy Centre (ICPC) is a leading voice in global debates on cyber and emerging technologies and their impact on broader strategic policy. -

Icnaam 2020 Conference

ICNAAM 2020 CONFERENCE VIRTUAL PARTICIPATION PROGRAM 17 September 2020 Virtual Room 1 08.50-09.00 Opening Ceremony Professor Dr. T.E. Simos (Chairman) Please note that Greek timezone is :(GMT+3) : Time now in Greece (Click Here) - 2 - 17 September 2020 Virtual Room 1 THE TENTH SYMPOSIUM ON ADVANCED COMPUTATION AND INFORMATION Session Name: IN NATURAL AND APPLIED SCIENCES Chair Name: Dr. Claus-Peter Rückemann Program: Hours Paper Title Author Claus-Peter 09.00-09.05 Welcome Notes Rückemann Keynote Lecture / Information Science and Structure: Claus-Peter 09.05-09.50 Beware – Ex Falso Quod Libet Rückemann Information Science Approaches to Sustainable Claus-Peter 09.50-10.25 Structures: Rhodos Case Results From Knowledge and Rückemann Mining 10.25-11.00 Mathematics in the Heart of Brunelleschi’s Dome Raffaella Pavani Session Recent advances in nonlinear partial differential equations and systems and their Name: applications Chair Name: G. R. Cirmi, S. D'Asero, S. Leonardi Program: Sept. 17 Hours Paper Title Author 11.00-11.30 On a class of nonlinear partial differential equations of parabolic type M. M. Porzio 11.35-12.05 Scalar and vectorial degenerate elliptic problems F. Leonetti 12.10-12.40 On some singular elliptic systems in R^N S. A. Marano THE BOTTARO-MARINA SLICE METHOD FOR DISTRIBUTIONAL 12.45-13.15 SOLUTIONS TO ELLIPTIC EQUATIONS WITH DRIFT TERM S. Buccheri Please note that Greek timezone is :(GMT+3) : Time now in Greece (Click Here) - 3 - Session Name: Statistical Inference in Copula Models and Markov Processes V Chair Name: Veronica Andrea Gonzalez-Lopez Program: Hours Paper Title Author A Stochastic Inspection about Genetic Variants of Jesús E. -

Códigos De Las Ayudas Concedidas

FECHA: 28/05/2020 CÓDIGOS DE LAS AYUDAS CONCEDIDAS CODIGO AYUDA DESCRIPCION AYUDA 2 Beca Básica 3 Cuantía Fija Ligada a la Renta 4 Cuantía Fija Ligada a la Residencia 5-1 Excelencia Académica entre 8 y 8.49 5-2 Excelencia Académica entre 8.50 y 8.99 5-3 Excelencia Académica entre 9 y 9.49 5-4 Excelencia Académica 9.50 o más 6 Cuantía variable mínima 7 Cuantía variable 8 Suplemento transporte marítimo/aéreo entre islas (para domiciliados en Tenerife, Gran Canaria o Mallorca) y entre Ceuta/Melilla y Península 9 Suplemento transporte marítimo/aéreo entre islas (para domiciliados en Lanzarote, Fuerteventura, Gomera, Hierro, La Palma, Menorca, Ibiza y Formentera) 10 Suplemento para transporte marítimo/aéreo a la Península para domiciliados en Baleares 11 Suplemento para transporte marítimo/aéreo a la Península para domiciliados en Canarias PAG: 1 de 407 RELACIÓN ALFABÉTICA DE BECARIOS CON LAS AYUDAS CONCEDIDAS FECHA: 28/05/2020 SANTA CRUZ DE TENERIFE CURSO: 2019-2020 CONVOCATORIA: General APELLIDOS - NOMBRE NIF/NIE AYUDAS IMPORTE TOTAL AABIDA ETTABTI, KARIMA ***4430** 3, 7 2.284,01 € AAGUIED SANNAD, MOHAMED ***9737** 3, 7 2.127,75 € ABAD HUME, SINEAD ***8124** 2, 5-2 275,00 € ABAD MARTIN, IRENE ANMARI ***0853** 3, 5-2, 7 2.589,39 € ABAD MARTIN, MERIEM ***0853** 3, 4, 7 4.848,38 € ABAD MARTIN, NIEVES MARIA ***0853** 3, 4, 7 4.874,50 € ABAD MARTÍN, EMILIO ***5943** 2, 7 715,40 € ABAD MESA, LAURA ***4075** 3, 7 2.111,16 € ABAD ROSQUETE, NELSON ***8529** 2, 7 663,02 € ABAD VELÁZQUEZ, RUT ***4191** 2, 5-2, 7 751,17 € ABALLA, HASNA ****0161* 3, -

China As Dystopia: Cultural Imaginings Through Translation Published In: Translation Studies (Taylor and Francis) Doi: 10.1080/1

China as dystopia: Cultural imaginings through translation Published in: Translation Studies (Taylor and Francis) doi: 10.1080/14781700.2015.1009937 Tong King Lee* School of Chinese, The University of Hong Kong *Email: [email protected] This article explores how China is represented in English translations of contemporary Chinese literature. It seeks to uncover the discourses at work in framing this literature for reception by an Anglophone readership, and to suggest how these discourses dovetail with meta-narratives on China circulating in the West. In addition to asking “what gets translated”, the article is interested in how Chinese authors and their works are positioned, marketed, and commodified in the West through the discursive material that surrounds a translated book. Drawing on English translations of works by Yan Lianke, Ma Jian, Chan Koonchung, Yu Hua, Su Tong, and Mo Yan, the article argues that literary translation is part of a wider programme of Anglophone textual practices that renders China an overdetermined sign pointing to a repressive, dystopic Other. The knowledge structures governing these textual practices circumscribe the ways in which China is imagined and articulated, thereby producing a discursive China. Keywords: translated Chinese literature; censorship; paratext; cultural politics; Yan Lianke Translated Literature, Global Circulations 1 In 2007, Yan Lianke (b.1958), a novelist who had garnered much critical attention in his native China but was relatively unknown in the Anglophone world, made his English debut with the novel Serve the People!, a translation by Julia Lovell of his Wei renmin fuwu (2005). The front cover of the book, published by London’s Constable,1 pictures two Chinese cadets in a kissing posture, against a white background with radiating red stripes. -

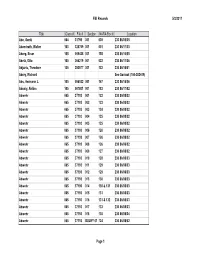

5/3/2011 FBI Records Page 1 Title Class # File # Section NARA Box

FBI Records 5/3/2011 Title Class # File # Section NARA Box # Location Abe, Genki 064 31798 001 039 230 86/05/05 Abendroth, Walter 100 325769 001 001 230 86/11/03 Aberg, Einar 105 009428 001 155 230 86/16/05 Abetz, Otto 100 004219 001 022 230 86/11/06 Abjanic, Theodore 105 253577 001 132 230 86/16/01 Abrey, Richard See Sovloot (100-382419) Abs, Hermann J. 105 056532 001 167 230 86/16/06 Abualy, Aldina 105 007801 001 183 230 86/17/02 Abwehr 065 37193 001 122 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 002 123 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 003 124 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 004 125 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 005 125 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 006 126 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 007 126 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 008 126 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 009 127 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 010 128 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 011 129 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 012 129 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 013 130 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 014 130 & 131 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 015 131 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 016 131 & 132 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 017 133 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 018 135 230 86/08/04 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 01 124 230 86/08/02 Page 1 FBI Records 5/3/2011 Title Class # File # Section NARA Box # Location Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 20 127 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 33 132 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 33 132 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 33 133 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 BULKY 35 134 230 86/08/03 Abwehr 065 37193 EBF 014X 123 230 86/08/02 Abwehr 065 37193 EBF 014X 123 230 86/08/02 Abwehr -

Critique of Anthropology

Critique of Anthropology http://coa.sagepub.com/ The state of irony in China Hans Steinmüller Critique of Anthropology 2011 31: 21 DOI: 10.1177/0308275X10393434 The online version of this article can be found at: http://coa.sagepub.com/content/31/1/21 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Critique of Anthropology can be found at: Email Alerts: http://coa.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://coa.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Citations: http://coa.sagepub.com/content/31/1/21.refs.html >> Version of Record - Mar 30, 2011 What is This? Downloaded from coa.sagepub.com at NATIONAL CHENGCHI UNIV LIB on February 23, 2012 Article Critique of Anthropology 31(1) 21–42 The state of irony ! The Author(s) 2011 Reprints and permissions: in China sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/0308275X10393434 coa.sagepub.com Hans Steinmu¨ller Department of Anthropology, London School of Economics Abstract In everyday life, people in China as elsewhere have to confront large-scale incongruities between different representations of history and state. They do so frequently by way of indirection, that is, by taking ironic, cynical or embarrassed positions. Those who understand such indirect expressions based on a shared experiential horizon form what I call a ‘community of complicity’. In examples drawn from everyday politics of memory, the representation of local development programmes and a dystopic novel, I distinguish cynicism and ‘true’ irony as two different ways to form such communities. This distinction proposes a renewed attempt at understanding social inclusion and exclusion. -

Congressional-Executive Commission on China Annual Report 2019

CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2019 ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION NOVEMBER 18, 2019 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: https://www.cecc.gov VerDate Nov 24 2008 13:38 Nov 18, 2019 Jkt 036743 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 5011 G:\ANNUAL REPORT\ANNUAL REPORT 2019\2019 AR GPO FILES\FRONTMATTER.TXT CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA ANNUAL REPORT 2019 ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION NOVEMBER 18, 2019 Printed for the use of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China ( Available via the World Wide Web: https://www.cecc.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 36–743 PDF WASHINGTON : 2019 VerDate Nov 24 2008 13:38 Nov 18, 2019 Jkt 036743 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 G:\ANNUAL REPORT\ANNUAL REPORT 2019\2019 AR GPO FILES\FRONTMATTER.TXT CONGRESSIONAL-EXECUTIVE COMMISSION ON CHINA LEGISLATIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS House Senate JAMES P. MCGOVERN, Massachusetts, MARCO RUBIO, Florida, Co-chair Chair JAMES LANKFORD, Oklahoma MARCY KAPTUR, Ohio TOM COTTON, Arkansas THOMAS SUOZZI, New York STEVE DAINES, Montana TOM MALINOWSKI, New Jersey TODD YOUNG, Indiana BEN MCADAMS, Utah DIANNE FEINSTEIN, California CHRISTOPHER SMITH, New Jersey JEFF MERKLEY, Oregon BRIAN MAST, Florida GARY PETERS, Michigan VICKY HARTZLER, Missouri ANGUS KING, Maine EXECUTIVE BRANCH COMMISSIONERS Department of State, To Be Appointed Department of Labor, To Be Appointed Department of Commerce, To Be Appointed At-Large, To Be Appointed At-Large, To Be Appointed JONATHAN STIVERS, Staff Director PETER MATTIS, Deputy Staff Director (II) VerDate Nov 24 2008 13:38 Nov 18, 2019 Jkt 036743 PO 00000 Frm 00004 Fmt 0486 Sfmt 0486 G:\ANNUAL REPORT\ANNUAL REPORT 2019\2019 AR GPO FILES\FRONTMATTER.TXT C O N T E N T S Page I. -

China Media Bulletin

Issue No. 119: May 2017 CHINA MEDIA BULLETIN Headlines FEATURE | Preparing for China’s next internet crackdown P1 BROADCAST / NEW MEDIA | In lawyers crackdown, authorities punish online speech, foreign media contacts P4 NEW MEDIA | New rules tighten control over online news P5 NEW MEDIA | Netizen conversations: Student death, anticorruption show, Great Firewall game P6 HONG KONG | Pressure on dissent increases amid press freedom decline P7 BEYOND CHINA | Confucius Institutes, Netflix market entry, China’s global media influence P8 NEW! FEATURED PRISONER | Zhang Haitao P10 WHAT TO WATCH FOR P10 NEW! TAKE ACTION P11 PHOTO OF THE MONTH A staged fight against corruption In the Name of the People, a new anticorruption drama on Hunan TV that was funded by the Supreme People’s Procuratorate, debuted on March 28. Cartoonist Rebel Pepper offers a skeptical take on the popular series, depicting it as a puppet show controlled by President Xi Jinping. Xi has overseen selective, politically fraught corruption probes against high-level officials, or “tigers.” The cartoonist writes, “If Xi Jinping hadn’t given his per- sonal approval, how could this show receive such high-profile publicity?” On April 20, the British group Index on Censorship announced that Rebel Pepper had received its 2017 Freedom of Expression Arts Fellow award. Credit: China Digital Times Visit http://freedomhou.se/cmb_signup or email [email protected] to subscribe or submit items. CHINA MEDIA BULLETIN: MAY 2017 FEATURE Preparing for China’s next internet crackdown By Sarah Cook China’s new Cybersecurity Law takes effect on June 1. Together with regulations issued Senior Research over the past month by the Cyber Administration of China (CAC)—including on news Analyst for East reporting and commentary—the new legal landscape threatens to tighten what is al- Asia at Freedom ready one of the world’s most restrictive online environments. -

Uyghur Experiences of Detention in Post-2015 Xinjiang 1

TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .........................................................................................................2 INTRODUCTION .....................................................................................................................9 METHODOLOGY ..................................................................................................................10 MAIN FINDINGS Surveillance and arrests in the XUAR ................................................................................13 Surveillance .......................................................................................................................13 Arrests ...............................................................................................................................15 Detention in the XUAR ........................................................................................................18 The detention environment in the XUAR ............................................................................18 Pre-trial detention facilities versus re-education camps ......................................................20 Treatment in detention facilities ..........................................................................................22 Detention as a site of political indoctrination and cultural cleansing....................................25 Violence in detention facilities ............................................................................................26 Possibilities for information -

Writing Memory

Corso di Dottorato di ricerca in Studi sull’Asia e sull’Africa, 30° ciclo ED 120 – Littérature française et comparée EA 172 Centre d'études et de recherches comparatistes WRITING MEMORY: GLOBAL CHINESE LITERATURE IN POLYGLOSSIA Thèse en cotutelle soutenue le 6 juillet 2018 à l’Université Ca’ Foscari Venezia en vue de l’obtention du grade académique de : Dottore di ricerca in Studi sull’Asia e sull’Africa (Ca’ Foscari), SSD: L-OR/21 Docteur en Littérature générale et comparée (Paris 3) Directeurs de recherche Mme Nicoletta Pesaro (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia) M. Yinde Zhang (Université Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3) Membres du jury M. Philippe Daros (Université Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3) Mme Barbara Leonesi (Università degli Studi di Torino) Mme Nicoletta Pesaro (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia) M. Yinde Zhang (Université Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3) Doctorante Martina Codeluppi Année académique 2017/18 Corso di Dottorato di ricerca in Studi sull’Asia e sull’Africa, 30° ciclo ED 120 – Littérature française et comparée EA 172 Centre d'études et de recherches comparatistes Tesi in cotutela con l’Université Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3: WRITING MEMORY: GLOBAL CHINESE LITERATURE IN POLYGLOSSIA SSD: L-OR/21 – Littérature générale et comparée Coordinatore del Dottorato Prof. Patrick Heinrich (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia) Supervisori Prof.ssa Nicoletta Pesaro (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia) Prof. Yinde Zhang (Université Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3) Dottoranda Martina Codeluppi Matricola 840376 3 Écrire la mémoire : littérature chinoise globale en polyglossie Résumé : Cette thèse vise à examiner la représentation des mémoires fictionnelles dans le cadre global de la littérature chinoise contemporaine, en montrant l’influence du déplacement et du translinguisme sur les œuvres des auteurs qui écrivent soit de la Chine continentale soit d’outre-mer, et qui s’expriment à travers des langues différentes. -

Reimagining Revolutionary Labor in the People's Commune

Reimagining Revolutionary Labor in the People’s Commune: Amateurism and Social Reproduction in the Maoist Countryside by Angie Baecker A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Asian Languages and Cultures) in the University of Michigan 2020 Doctoral Committee: Professor Xiaobing Tang, Co-Chair, Chinese University of Hong Kong Associate Professor Emily Wilcox, Co-Chair Professor Geoff Eley Professor Rebecca Karl, New York University Associate Professor Youngju Ryu Angie Baecker [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0003-0182-0257 © Angie Baecker 2020 Dedication This dissertation is dedicated to my grandmother, Chang-chang Feng 馮張章 (1921– 2016). In her life, she chose for herself the penname Zhang Yuhuan 張宇寰. She remains my guiding star. ii Acknowledgements Nobody writes a dissertation alone, and many people’s labor has facilitated my own. My scholarship has been borne by a great many networks of support, both formal and informal, and indeed it would go against the principles of my work to believe that I have been able to come this far all on my own. Many of the people and systems that have enabled me to complete my dissertation remain invisible to me, and I will only ever be able to make a partial account of all of the support I have received, which is as follows: Thanks go first to the members of my committee. To Xiaobing Tang, I am grateful above all for believing in me. Texts that we have read together in numerous courses and conversations remain cornerstones of my thinking. He has always greeted my most ambitious arguments with enthusiasm, and has pushed me to reach for higher levels of achievement.