U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lactational Amenorrhea Method

Lactational Amenorrhea Method Dr. Raqibat Idris [email protected] From Research to Practice: Training in Sexual and Reproductive Health Research 2017 Objectives of presentation • Define Lactational Amenorrhea Method (LAM) • Understand the mechanism of action of LAM • Know the efficacy of LAM • Know and describe the 3 criteria for LAM • Know the indication and contraindications for LAM • Know the focus and timing of counselling for LAM • List the advantages, disadvantages and health benefits of LAM • Know the elements of programming necessary for the provision of quality LAM services Introduction Breastfeeding delays the return of a woman’s fertility in the first few months following childbirth. Women who breastfeed are less likely to ovulate in this period. When compared with women who breastfeed partially or who do not breastfeed at all, women who breastfeed more intensively are less likely to have a normal ovulation before their first menstrual bleed postpartum (Berens et al., 2015). In a consensus meeting in Bellagio, Italy in 1998, scientists proposed that women who breastfeed fully or nearly fully while they remain amenorrhoeic in the first 6 months postpartum experience up to 98% protection from pregnancy. This formed the basis for the Lactational Amenorrhea Method and has since then been tested and confirmed by other studies (Berens et al., 2015; Van der Wijden et al., 2003; WHO, 1999). Berens P, Labbok M, The Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine. ABM Clinical Protocol #13: Contraception During Breastfeeding, Revised 2015. Breastfeeding Medicine. 2015 Feb;10(1):3-12. The World Health Organization multinational study of breast-feeding and lactational amenorrhea. III. -

A History of Birth Control Methods

Report Published by the Katharine Dexter McCormick Library and the Education Division of Planned Parenthood Federation of America 434 West 33rd Street, New York, NY 10001 212-261-4716 www.plannedparenthood.org Current as of January 2012 A History of Birth Control Methods Contemporary studies show that, out of a list of eight somewhat effective — though not always safe or reasons for having sex, having a baby is the least practical (Riddle, 1992). frequent motivator for most people (Hill, 1997). This seems to have been true for all people at all times. Planned Parenthood is very proud of the historical Ever since the dawn of history, women and men role it continues to play in making safe and effective have wanted to be able to decide when and whether family planning available to women and men around to have a child. Contraceptives have been used in the world — from 1916, when Margaret Sanger one form or another for thousands of years opened the first birth control clinic in America; to throughout human history and even prehistory. In 1950, when Planned Parenthood underwrote the fact, family planning has always been widely initial search for a superlative oral contraceptive; to practiced, even in societies dominated by social, 1965, when Planned Parenthood of Connecticut won political, or religious codes that require people to “be the U.S. Supreme Court victory, Griswold v. fruitful and multiply” — from the era of Pericles in Connecticut (1965), that finally and completely rolled ancient Athens to that of Pope Benedict XVI, today back state and local laws that had outlawed the use (Blundell, 1995; Himes, 1963; Pomeroy, 1975; Wills, of contraception by married couples; to today, when 2000). -

Integrating Complementary Medicine Into Cardiovascular Medicine

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Journal of the American College of Cardiology Vol. 46, No. 1, 2005 © 2005 by the American College of Cardiology Foundation ISSN 0735-1097/05/$30.00 Published by Elsevier Inc. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2005.05.031 ACCF COMPLEMENTARY MEDICINE EXPERT CONSENSUS DOCUMENT Integrating Complementary Medicine Into Cardiovascular Medicine A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents (Writing Committee to Develop an Expert Consensus Document on Complementary and Integrative Medicine) WRITING COMMITTEE MEMBERS JOHN H. K. VOGEL, MD, MACC, Chair STEVEN F. BOLLING, MD, FACC BRIAN OLSHANSKY, MD, FACC REBECCA B. COSTELLO, PHD KENNETH R. PELLETIER, MD(HC), PHD ERMINIA M. GUARNERI, MD, FACC CYNTHIA M. TRACY, MD, FACC MITCHELL W. KRUCOFF, MD, FACC, FCCP ROBERT A. VOGEL, MD, FACC JOHN C. LONGHURST, MD, PHD, FACC TASK FORCE MEMBERS ROBERT A. VOGEL, MD, FACC, Chair JONATHAN ABRAMS, MD, FACC SANJIV KAUL, MBBS, FACC JEFFREY L. ANDERSON, MD, FACC ROBERT C. LICHTENBERG, MD, FACC ERIC R. BATES, MD, FACC JONATHAN R. LINDNER, MD, FACC BRUCE R. BRODIE, MD, FACC* ROBERT A. O’ROURKE, MD, FACC† CINDY L. GRINES, MD, FACC GERALD M. POHOST, MD, FACC PETER G. DANIAS, MD, PHD, FACC* RICHARD S. SCHOFIELD, MD, FACC GABRIEL GREGORATOS, MD, FACC* SAMUEL J. SHUBROOKS, MD, FACC MARK A. HLATKY, MD, FACC CYNTHIA M. TRACY, MD, FACC* JUDITH S. HOCHMAN, MD, FACC* WILLIAM L. WINTERS, JR, MD, MACC* *Former members of Task Force; †Former chair of Task Force The recommendations set forth in this report are those of the Writing Committee and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the American College of Cardiology Foundation. -

The National Drugs List

^ ^ ^ ^ ^[ ^ The National Drugs List Of Syrian Arab Republic Sexth Edition 2006 ! " # "$ % &'() " # * +$, -. / & 0 /+12 3 4" 5 "$ . "$ 67"5,) 0 " /! !2 4? @ % 88 9 3: " # "$ ;+<=2 – G# H H2 I) – 6( – 65 : A B C "5 : , D )* . J!* HK"3 H"$ T ) 4 B K<) +$ LMA N O 3 4P<B &Q / RS ) H< C4VH /430 / 1988 V W* < C A GQ ") 4V / 1000 / C4VH /820 / 2001 V XX K<# C ,V /500 / 1992 V "!X V /946 / 2004 V Z < C V /914 / 2003 V ) < ] +$, [2 / ,) @# @ S%Q2 J"= [ &<\ @ +$ LMA 1 O \ . S X '( ^ & M_ `AB @ &' 3 4" + @ V= 4 )\ " : N " # "$ 6 ) G" 3Q + a C G /<"B d3: C K7 e , fM 4 Q b"$ " < $\ c"7: 5) G . HHH3Q J # Hg ' V"h 6< G* H5 !" # $%" & $' ,* ( )* + 2 ا اوا ادو +% 5 j 2 i1 6 B J' 6<X " 6"[ i2 "$ "< * i3 10 6 i4 11 6! ^ i5 13 6<X "!# * i6 15 7 G!, 6 - k 24"$d dl ?K V *4V h 63[46 ' i8 19 Adl 20 "( 2 i9 20 G Q) 6 i10 20 a 6 m[, 6 i11 21 ?K V $n i12 21 "% * i13 23 b+ 6 i14 23 oe C * i15 24 !, 2 6\ i16 25 C V pq * i17 26 ( S 6) 1, ++ &"r i19 3 +% 27 G 6 ""% i19 28 ^ Ks 2 i20 31 % Ks 2 i21 32 s * i22 35 " " * i23 37 "$ * i24 38 6" i25 39 V t h Gu* v!* 2 i26 39 ( 2 i27 40 B w< Ks 2 i28 40 d C &"r i29 42 "' 6 i30 42 " * i31 42 ":< * i32 5 ./ 0" -33 4 : ANAESTHETICS $ 1 2 -1 :GENERAL ANAESTHETICS AND OXYGEN 4 $1 2 2- ATRACURIUM BESYLATE DROPERIDOL ETHER FENTANYL HALOTHANE ISOFLURANE KETAMINE HCL NITROUS OXIDE OXYGEN PROPOFOL REMIFENTANIL SEVOFLURANE SUFENTANIL THIOPENTAL :LOCAL ANAESTHETICS !67$1 2 -5 AMYLEINE HCL=AMYLOCAINE ARTICAINE BENZOCAINE BUPIVACAINE CINCHOCAINE LIDOCAINE MEPIVACAINE OXETHAZAINE PRAMOXINE PRILOCAINE PREOPERATIVE MEDICATION & SEDATION FOR 9*: ;< " 2 -8 : : SHORT -TERM PROCEDURES ATROPINE DIAZEPAM INJ. -

Investigation of Influence of Diazepam, Valproate, Cyproheptadine and Cortisol on the Rewarding Ventral Tegmental Self-Stimulation Behaviour

Ind. J. Physio!. Pharmac., Volume 33, Number 3, 1989 INVESTIGATION OF INFLUENCE OF DIAZEPAM, VALPROATE, CYPROHEPTADINE AND CORTISOL ON THE REWARDING VENTRAL TEGMENTAL SELF-STIMULATION BEHAVIOUR SONTI V. RAMANA AND T. DESIRAJU· Department ofNeurophysiology, National Institute of Mental Health arzd Neuro Sciences, Bangalore - 560 029 ( Received on June IS, 1989 ) Abstract: Experiments were carried on in the Wistar rats having self-stimulation (88) electrodes implanted chronically in substantia nigra-ventral tegmental area (SN-VTA) to examine whether modulations of GABAergic, serotonergic, histaminergic, dopaminergic, and glucocorticoid neuronal receptor functions will affect or not the brain reward system and the 88 behaviour. The modulalon are the wellknown drugs: diazepam which is a facilitator ohome of the GABA recepton, and used clinically (or its tranquilising, anxiolytic, sedative-hypnotic and anti-convulsant properties: sodium valproate which is known to enhance the GABA synapse function, and used clinically for its anti convulsant property; haloperidol which is a dopaminergic receptor (D2) blocker, and clinically used for its anti-psychotic property; cyproheptadine which is both anti-histaminic and anti-serotonergic (blocka 5-HT2 receptor), used clinically for its antihistaminic and other beneficial properties; and hydrocortisone which is the stress-resisting glucocorticoid having direct effects on both brain and body cells, used clinically for the wide-ranging glucocorticoid therapeutic effects. The results revealed that systemic administration of these drugs, except haloperidol, caused no significant influenee on the 88 behaviour, thereby indicating that these nondopaminergic drugs have no effect on brain-reward system and also these categories of synaptic actions are not likely to be involved in the primary organization of the mechanisms of the brain-reward system. -

Sterilization and Abortion Policy Billing Instructions

Sterilization and Abortion Policy Billing Instructions Table of contents Table of contents ...................................................................................................................................... 1 Hysterectomy ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Acknowledgement forms ..................................................................................................................... 2 Prior authorization requirements ......................................................................................................... 2 Covered services ................................................................................................................................... 2 Intrauterine Devices and Subdermal Implants ......................................................................................... 4 Family planning: sterilization .................................................................................................................... 4 Prior authorization requirements ......................................................................................................... 5 Covered services ................................................................................................................................... 5 Abortion .................................................................................................................................................... 6 Claim -

INTRAUTERINE INSEMINATION of HUSBAND's SEMEN Departments

INTRAUTERINE INSEMINATION OF HUSBAND'S SEMEN B. N. BARWIN Departments of Physiology and Midwifery & Gynaecology, The Queen's University of Belfast, Northern Ireland (Received 11 th January 1973) Summary. Fifty patients with primary infertility were treated by intra- uterine insemination of the husband's semen which had been stored. Thirty patients had sperm counts of greater than 20 \m=x\106/ml with 50% motility and twenty patients had oligospermia (<20 \m=x\106/ml). The technique of storage of semen is reported and the intrauterine method described. The r\l=o^\leof the buffer solution is discussed in over- coming the complications of intrauterine insemination. A success rate of 70% is reported in the normospermic group and 55% in the oligo- spermic group over nine cycles of intrauterine insemination of husband's semen. INTRODUCTION One of the main problems confronting the gynaecologist in the investigation of infertility is the consistent finding of immotile spermatozoa, spermatozoa of low motility and low sperm count in the cervical mucus or semen (Scott, 1968). There was considerable controversy among earlier workers in the field that the sperm count was substandard if it fell below 60 106/ml but MacLeod (1962) has carried out considerable research in this field and it is now generally accepted that true oligospermia is represented by counts of less than 20 IO6/ ml provided the motility is good. SUBJECTS AND METHODS Selection of cases Fifty couples with primary infertility of between 3 and 14 years' duration were selected. The age distribution was between 24 and 41 years. In all cases, the wives had been subjected to a full clinical investigation. -

American Family Physician

Natural Family Planning - American Family Physician http://www.aafp.org/afp/2012/1115/p924.html BRIAN A. SMOLEY, CDR, MC, USN, Camp Pendleton, California CHRISTA M. ROBINSON, LCDR, MC, USN, Naval Hospital Lemoore, Lemoore Station, California Am Fam Physician. 2012 Nov 15;86(10):924-928. Related editorials: Is Natural Family Planning a Highly Effective Method of Birth Control? Yes: Natural Family Planning is Highly Effective and Fulfilling (http://www.aafp.org/afp/2012/1115/od1.html) and No: Family Natural Family Planning Methods Are Overrrated (http://www.aafp.org/afp/2012/1115/od2.html). Patient information: See related handout on natural family planning (http://www.aafp.org/afp/2012/1115/p924-s1.html), written by the authors of this article. Related letter: Physicians Need More Education About Natural Family Planning (http://www.aafp.org/afp/2013/0801/p158.html) Natural family planning methods provide a unique option for committed couples. Advantages include the lack of medical adverse effects and the opportunity for participants to learn about reproduction. Modern methods of natural family planning involve observation of biologic markers to identify fertile days in a woman's reproductive cycle. The timing of intercourse can be planned to achieve or avoid pregnancy based on the identified fertile period. The current evidence for effectiveness of natural family planning methods is limited to lower-quality clinical trials without control groups. Nevertheless, perfect use of these methods is reported to be at least 95 percent effective in preventing pregnancy. The effectiveness of typical use is 76 percent, which demonstrates that motivation and commitment to the method are essential for success. -

PMBJP Product.Pdf

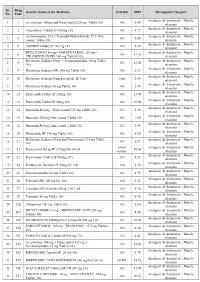

Sr. Drug Generic Name of the Medicine Unit Size MRP Therapeutic Category No. Code Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 1 1 Aceclofenac 100mg and Paracetamol 325 mg Tablet 10's 10's 8.00 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 2 2 Aceclofenac Tablets IP 100mg 10's 10's 4.37 relaxants Acetaminophen 325 + Tramadol Hydrochloride 37.5 film Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 3 4 10's 8.00 coated Tablet 10's relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 4 5 ASPIRIN Tablets IP 150 mg 14's 14's 2.70 relaxants DICLOFENAC 50 mg+ PARACETAMOL 325 mg+ Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 5 6 10's 11.30 CHLORZOXAZONE 500 mg Tablets 10's relaxants Diclofenac Sodium 50mg + Serratiopeptidase 10mg Tablet Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 6 8 10's 12.00 10's relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 7 9 Diclofenac Sodium (SR) 100 mg Tablet 10's 10's 6.12 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 8 10 Diclofenac Sodium 25mg per ml Inj. IP 3 ml 3 ml 2.00 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 9 11 Diclofenac Sodium 50 mg Tablet 10's 10's 2.90 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 10 12 Etoricoxilb Tablets IP 120mg 10's 10's 33.00 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 11 13 Etoricoxilb Tablets IP 90mg 10's 10's 25.00 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 12 14 Ibuprofen 400 mg + Paracetamol 325 mg Tablet 10's 15's 5.50 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 13 15 Ibuprofen 200 mg film coated Tablet 10's 10's 1.80 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic / Muscle 14 16 Ibuprofen 400 mg film coated Tablet 10's 15's 3.50 relaxants Analgesic & Antipyretic -

Contraception and Misconceptions

CONTRACEPTION AND MISCONCEPTIONS CONTRACEPTION IN WOMEN WITH MENTAL ILLNESS OVERVIEW Hormones and mood How mental illness impacts on contraceptive choice Ideal contraception Pro and cons of contraceptive methods in women with mental illness Hormonal contraception and mood ESTROGENS anti-inflammatory neuroprotective effects of estradiol modulation of the limbic processing memory of emotionally-relevant information. estradiol “beneficially” modulates pathways implicated in the pathophysiology of depression, including serotonin and norepinephrine pathways PROGESTROGENS Previously thought to be anxiogenic, depressogenic Breakdown products Depression – alpha hydroxy progestrogen breakdown products pro – inflammatory, anxiogenic HORMONES AND MOODS – COMPLEX INTERPLAY MENTAL ILLNESS AND CONTRACEPTIVE CHOICE Effect of mental illness on contraceptive choice Effect of contraceptive choice on mental illness Drug interactions EFFECT MENTAL ILLNESS ON CONTRACEPTIVE CHOICE Impulsive Poor planning Cognitive and problem judgement Poor adherence IMPULSIVITY COGNITION POOR JUDGEMENT LETS NOT FORGET SUBSTANCES…… TYPES OF CONTRACEPTION No method Non hormonal Condom/Femidom Diaphragm Non hormone containing IUCD (Copper T) Hormonal COC POP Mirena Evra Patch Nuva Ring Implant ORAL CONTRACEPTIVES POP – avoid Same time every day COC Pros Effective Reduction PMS – monophasic estrogen dominant pill eg Femodene, Yaz, Nordette Cons Drug interactions Pill burden Daily dose EVRA PATCH Weekly patch Transdermal system: 150 mcg/day -

Which Contraceptive Is Right for You?

IT’S NOT A MATTER OF LUCK! WHICH CONTRACEPTIVE IS RIGHT FOR YOU? @FIUHLP FIU Healthy @FIUHLP FIUHLP @FIUHLPRD Living Program BEFORE YOU GET BUSY…. Prescription/ Can Be Used Pregnancy Doctor’s Protects Contraception Ahead of Time Prevention Visit Need Against STI’s Key Hormonal Available at SHC The N/A Pill/Patch/Ring 90% Yes No N/A Hormonal IUD 99% Yes No N/A Implant 99% Yes No The Shot N/A 99% Yes No Non-Hormonal No Male Condoms 80% No Yes Female Yes Condoms 80% No Yes N/A Copper IUD 99% Yes No Yes Diaphragm 90% Yes No No Spermicide 70% No No Fertility Yes Awareness 75% No No *Pregnancy and STI prevention Sterilization N/A Almost 100% Yes No depends on personal consistent N/A Withdrawal 70% No No Yes and correct use.* Abstinence 100% No Yes Hormonal Spermicide The Pill/Patch/Ring Kills sperm Available in jelly, foam, cream, suppositories, and film Release hormones to inhibit the body’s natural Spermicide must be reapplied every time before sex cyclical hormones to help prevent pregnancy Provides poor protection against pregnancy itself - more Suppress ovulation, thicken the cervical mucus, and effective when used with a barrier method thin the lining of the womb • The Pill must be taken daily. Cervical Cap • The Patch must be replaced weekly. Treated with spermicide • The Ring can be worn for 3 weeks. Can be inserted before sex, and must be left in place 6 hours afterward Hormonal IUD Spermicide must be reapplied every time before sex Requires a doctor’s visit for fitting and another to ensure correct use Thickens cervical mucus and -

209627Orig1s000

CENTER FOR DRUG EVALUATION AND RESEARCH APPLICATION NUMBER: 209627Orig1s000 MULTI-DISCIPLINE REVIEW Summary Review Office Director Cross Discipline Team Leader Review Clinical Review Non-Clinical Review Statistical Review Clinical Pharmacology Review Reviewers of Multi-Disciplinary Review and Evaluation SECTIONS OFFICE/ AUTHORED/ ACKNOWLEDGED/ DISCIPLINE REVIEWER DIVISION APPROVED Mark Seggel, Ph.D. OPQ/ONDP/DNDP2 Authored: Section 4.2 Digitally signed by Mark R. Seggel -S CMC Lead DN: c=US, o=U.S. Government, ou=HHS, ou=FDA, ou=People, cn=Mark R. Signature: Mark R. Seggel -S Seggel -S, 0.9.2342.19200300.100.1.1=1300071539 Date: 2018.08.08 16:29:15 -04'00' Frederic Moulin, DVM, PhD OND/ODE3/DBRUP Authored: Section 5 Pharmacology/ Digitally signed by Frederic Moulin -S Toxicology DN: c=US, o=U.S. Government, ou=HHS, ou=FDA, ou=People, Reviewer Signature: Frederic Moulin -S 0.9.2342.19200300.100.1.1=2001708658, cn=Frederic Moulin -S Date: 2018.08.08 15:26:57 -04'00' Kimberly Hatfield, PhD OND/ODE3/DBRUP Approved: Section 5 Pharmacology/ Toxicology Digitally signed by Kimberly P. Hatfield -S DN: c=US, o=U.S. Government, ou=HHS, ou=FDA, ou=People, Team Leader Signature: Kimberly P. Hatfield -S 0.9.2342.19200300.100.1.1=1300387215, cn=Kimberly P. Hatfield -S Date: 2018.08.08 14:56:10 -04'00' Li Li, Ph.D. OCP/DCP3 Authored: Sections 6 and 17.3 Clinical Pharmacology Dig ta ly signed by Li Li S DN c=US o=U S Government ou=HHS ou=FDA ou=People Reviewer cn=Li Li S Signature: Li Li -S 0 9 2342 19200300 100 1 1=20005 08577 Date 2018 08 08 15 39 23 04'00' Doanh Tran, Ph.D.