The History of Cartography, Volume 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHAPTER 11 the Italian Renaissance and Beyond: The

CHAPTER 11 The Italian Renaissance and Beyond: The Politics of Culture, 1350 - 1550 CHAPTER OUTLINE I. The Cradle of the Renaissance: The Italian City-States Renaissance Italy was distinguished by the large number and political autonomy of its thriving city-states, the development of which can be divided into two distinct phases: the republicanism phase of the eleventh century and the principality phase of the fourteenth century. A. The Renaissance Republics: Florence and Venice In contrast to the majority of the Italian city-states, Florence and Venice held steadfastly to the traditions of republicanism under the patriciate system of political and artistic influence by a few great families. 1. Florence Under the Medici The amazingly wealthy banker Cosimo de' Medici emerged as the greatest of the Renaissance patrons. Seizing Florentine political power in 1434, Cosimo enforced a long period of unprecedented peace in which the arts could flourish. Always at the center of Florence's political affairs, Cosimo nevertheless rarely held formal office and shrewdly preferred to leverage influence behind the scenes. 2. Venice, the Cosmopolitan Republic Venice, the first European power to control colonies abroad, conquered a number of ports along the Geek coast. The resulting influx of exotic goods transformed Venice into a giant in the economics of the region and cosmopolitan in its social scope. Defined primarily by its social stability, the Venetian city- state became (and still is) the longest surviving republic in history at roughly five hundred years of independent affluence. B. Princes and Courtiers The ideals of the Renaissance, though created within the republican city-states, soon spread to the principalities ruled by one man (the prince). -

The Treaty of Lunéville J. David Markham When Napoleon Became

The Treaty of Lunéville J. David Markham When Napoleon became First Consul in 1799, his first order of business was to defend France against the so-called Second Coalition. This coalition was made up of a number of smaller countries led by Austria, Russia and Britain. The Austrians had armies in Germany and in Piedmont, Italy. Napoleon sent General Jean Moreau to Germany while he, Napoleon, marched through Switzerland to Milan and then further south, toward Alessandria. As Napoleon, as First Consul, was not technically able to lead an army, the French were technically under the command of General Louis Alexandre Berthier. There, on 14 June 1800, the French defeated the Austrian army led by General Michael von Melas. This victory, coupled with Moreau’s success in Germany, lead to a general peace negotiation resulting in the Treaty of Lunéville (named after the town in France where the treaty was signed by Count Ludwig von Cobenzl for Austria and Joseph Bonaparte for Austria. The treaty secured France’s borders on the left bank of the Rhine River and the Grand Duchy of Tuscany. France ceded territory and fortresses on the right bank, and various republics were guaranteed their independence. This translation is taken from the website of the Fondation Napoléon and can be found at the following URL: https://www.napoleon.org/en/history-of-the- two-empires/articles/treaty-of-luneville/. I am deeply grateful for the permission granted to use it by Dr. Peter Hicks of the Fondation. That French organization does an outstanding job of promoting Napoleonic history throughout the world. -

Castle of Olivola

Castle of Olivola AULLA Location: Olivola is a medieval village located on a hill, rising 300 metres above sea level in the heart of the region of Lunigiana, east of Aulla. Type of castle: Marquis’ seat. Construction period: The castle was probably built in the 13th century and later extended and restored by Lazzaro I Malaspina in the 16th century. First appearance in historical sources: Olivola was first mentioned in a document of 1234, in which Obizzo Malaspina granted “to Salio of Verrucola all personal and material rights of Berta, daughter of Alberto of Olivola, in fief”. Strategic role: From its elevated position, the castle overlooked the hills between the Taverone and Aulella rivers, playing an important role as stronghold for the defence of the Malaspina territory. Castle of Olivola AULLA Further use: The slow decay of the Castle of Olivola began in 1638, when the Marquis History: The castle and the village were strongholds for the defence of the Malaspina Spinetta II moved the old feudal seat to Pallerone, giving rise to the dynasty of the Marquises territory and, as 13th-century documents show, they were part of the Filattiera fief. In 1275, of Olivola-Pallerone. According to Formentini, the Castle of Olivola was militarily equipped the amount of land inherited by Francesco Malaspina included a large territory between until the end of the feudal system; in its last days it was provided with just four pieces of the Aulella and Taverone rivers. Olivola became the marquis’ seat of this new fief, which ordnance. included several villages, such as Fornoli, Virgoletta, Panicale, Monti, Pontebosio, Bastia, Montevignale, Tavernelle, Varano, Apella, Groppo San Pietro, Agnino, Bigliolo, Aulla, Current condition: The last remains of the castle are the ruins of the walls and two large Bibola and Pallerone. -

Piano Comunale Per L'esercizio Del Commercio Su Aree Pubbliche

COMUNE DI MONTECARLO Provincia di Lucca SPORTELLO UNICO ATTIVITA’ PRODUTTIVE PIANO COMUNALE PER L’ESERCIZIO DEL COMMERCIO SU AREE PUBBLICHE COMUNE DI MONTECARLO Provincia di Lucca SPORTELLO UNICO ATTIVITA’ PRODUTTIVE 1. QUADRO DI RIFERIMENTO 2 TERRITORIO ED ECONOMIA 3 RICOGNIZIONE DEI MERCATI E DELLE FIERE ESISTENTI 4 INDIVIDUAZIONE DELLE AREE IN CUI E’ VIETATA L’ATTIVITA’ DI COMMERCIO ITINERANTE REGOLAMENTO PER LA DISCIPLINA DELLO SVOLGIMENTO DELL’ATTIVITA’ COMMERCIALE SULLE AREE PUBBLICHE 2 COMUNE DI MONTECARLO Provincia di Lucca SPORTELLO UNICO ATTIVITA’ PRODUTTIVE 1. QUADRO DI RIFERIMENTO Il presente piano è adottato in attuazione del combinato disposto dell’art.10 Legge Regionale 4.02.2003 n. 10 “ Norme per la disciplina del commercio su aree pubbliche” e dell’art. 8 D.P.G.R. 4.06.2003 n. 29/R Regolamento di attuazione della Legge Regionale suddetta. La disciplina Comunale per il commercio su aree pubbliche è contenuta nel regolamento Comunale allegato al presente piano quale parte integrante e sostanziale. Il piano è corredato di cartografie e planimetrie delle aree destinate al commercio su aree pubbliche e delle zone del territorio comunale in cui è vietato il commercio in forma itinerante. Il Piano ha validità triennale dalla data di approvazione e può essere modificato e aggiornato con le stesse modalità previste per l’approvazione. 2 POPOLAZIONE TERRITORIO ED ECONOMIA La popolazione residente nel comune di Montecarlo al 31.12.2003 è di 4388 abitanti, con una densità abitativa di circa 280 abitanti per kmq ed in costante crescita dal 1969.: I valori del suo sviluppo vedono nel periodo compreso tra il 1969 ed il 2003 un incremento nel numero di abitanti pari a 1.023 persone, con una media che si attesta intorno all’1%. -

Funding of the Papal Army's Campaign to Germany During The

9 Petr VOREL Funding of the Papal Army’s Campaign to Germany during the Schmalkaldic War (Edition of the original accounting documentation “Conto de la Guerra de Allemagna” kept by the Pope’s accountant Pietro Giovanni Aleotti from 22 June 1546 to 2 September 1547) Abstract: This article is based on the recently discovered text of accounting documentation led by the Papal secret accountant Pietro Giovanni Aleotti. He kept records of income and expenses of Papal chamber connected with the campaign of Papal army that was sent from Italy to Germany by Pope Paul III (Alessandro Farnese) in the frame of the first period of so called Smalkaldic War (1546–1547). The author publishes this unique source in extenso and completes the edition by the detailed analysis of the incomes and expenses of this documentation. The analysis is extended by three partial texts dealing with 1) so called Jewish tax that was announced by Paul III in the financial support of military campaign, 2) credit granting of this campaign by the bank house of Benvenuto Olivieri in connection with the collection of Papal tithe in the Romagna region and 3) staffing of the commanding officers of Papal army during this campaign (in the attachment one can find a reconstruction of the officers’ staff with identification of the most important commanders). In the conclusion the author tries to determine the real motives why Paul III decided to take part in this campaign. In comparison to the previous works the author accents mainly the efforts of the Farnese family to raise their prestige at the end of the pontificate of Paul III and their immediate financial interests that are reflected in the account documentation. -

Touring a Unified Italy, Part 2 by John F

Browsing the Web: Touring A Unified Italy, Part 2 by John F. Dunn We left off last month on our tour of Italy—commemo- rating the 150th Anniversary of the Unification of the na- tion—with a relaxing stop on the island of Sardinia. This “Browsing the Web” was in- spired by the re- lease by Italy of two souvenir sheets to celebrate the Unifi- cation. Since then, on June 2, Italy released eight more souvenir sheets de- picting patriots of the Unification as well as a joint issue with San Marino (pictured here, the Italian issue) honoring Giuseppe and Anita Garibaldi, Anita being the Brazilian wife and comrade in arms of the Italian lead- er. The sheet also commemorates the 150th Anniversary of the granting of San Marino citizen- ship to Giuseppe Garibaldi. As we continue heading south, I reproduce again the map from Part 1 of this article. (Should you want Issue 7 - July 1, 2011 - StampNewsOnline.net 10 to refresh your memory, you can go to the Stamp News Online home page and select the Index by Subject in the upper right to access all previous Stamp News Online ar- ticles, including Unified Italy Part 1. So…moving right along (and still in the north), we next come to Parma, which also is one of the Italian States that issued its own pre-Unification era stamps. Modena Modena was founded in the 3rd century B.C. by the Celts and later, as part of the Roman Empire and became an important agricultural center. After the barbarian inva- sions, the town resumed its commercial activities and, in the 9th century, built its first circle of walls, which continued throughout the Middle Ages, until they were demolished in the 19th century. -

My Via Francigena Pilgrimage

My Via Francigena Pilgrimage No man is brave that has never walked a hundred miles. If you want to know the truth of who you are, walk until not a person knows your name. Travel is the great leveller, the great teacher, bitter as medicine, crueler than mirror- glass. A long stretch of road will teach you more about yourself than a hundred years of quiet. – Patrick Rothfuss, American writer he Road to Rome or Via Francigena to Rome is – like the Camino de Santiago de Compostela – an historic medieval route that takes pilgrims on an epic journey through some of Europe's most stunning regions from Canterbury, TEngland, across the channel to France, and through Switzerland, before crossing Italy on their way to the tomb of St Peter in Rome. The Via Francigena was named a European Cultural Route by the Council of Europe in 1994. It was the year 990 when Sigeric, the Archbishop of Canterbury, travelled to Rome to receive his pallium (papal investiture) from the pope. On his return, Sigeric made notes of all 79 stops he made, which he called submansiones, in his travel diary. Today it is an immensely important historic document that allows us to reconstruct what was very likely the most used pilgrimage path around the year 1000. But the history of the Via Francigena is more than just Sigeric's words, and stretches even further back in time. The origins of the route date to the Lombards, who by the 6th century were crossing Monte Bardone, between Berceto (Emilia-Romagna) and Pontremoli (Tuscany), near what is today Passo della Cisa (Liguria) in the Apennine Alps, a secure route for reaching the historic maritime destinations of Luni (Liguria) and Tuscia, far from the routes controlled by the Byzantines, their undeniable enemies. -

Machiavelli: the Prince

The Prince by Niccolo Machiavelli The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Prince, by Nicolo Machiavelli This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Prince Author: Nicolo Machiavelli Translator: W. K. Marriott Release Date: February 11, 2006 [EBook #1232] Last Updated: November 5, 2012 Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE PRINCE *** Produced by John Bickers, David Widger and Others THE PRINCE by Nicolo Machiavelli Translated by W. K. Marriott Nicolo Machiavelli, born at Florence on 3rd May 1469. From 1494 to 1512 held an official post at Florence which included diplomatic missions to various European courts. Imprisoned in Florence, 1512; later exiled and returned to San Casciano. Died at Florence on 22nd June 1527. CONTENTS INTRODUCTION YOUTH Aet. 1-25—1469-94 OFFICE Aet. 25-43—1494-1512 LITERATURE AND DEATH Aet. 43-58—1512-27 THE MAN AND HIS WORKS DEDICATION THE PRINCE CHAPTER I HOW MANY KINDS OF PRINCIPALITIES THERE ARE CHAPTER II CONCERNING HEREDITARY PRINCIPALITIES CHAPTER III CONCERNING MIXED PRINCIPALITIES CHAPTER IV WHY THE KINGDOM OF DARIUS, CONQUERED BY ALEXANDER CHAPTER V CONCERNING THE WAY TO GOVERN CITIES OR PRINCIPALITIES CHAPTER VI CONCERNING NEW PRINCIPALITIES WHICH ARE ACQUIRED CHAPTER VII CONCERNING NEW PRINCIPALITIES WHICH ARE ACQUIRED CHAPTER VIII CONCERNING -

Mapping Robert Storr

Mapping Robert Storr Author Storr, Robert Date 1994 Publisher The Museum of Modern Art: Distributed by H.N. Abrams ISBN 0870701215, 0810961407 Exhibition URL www.moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/436 The Museum of Modern Art's exhibition history— from our founding in 1929 to the present—is available online. It includes exhibition catalogues, primary documents, installation views, and an index of participating artists. MoMA © 2017 The Museum of Modern Art bk 99 £ 05?'^ £ t***>rij tuin .' tTTTTl.l-H7—1 gm*: \KN^ ( Ciji rsjn rr &n^ u *Trr» 4 ^ 4 figS w A £ MoMA Mapping Robert Storr THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK DISTRIBUTED BY HARRY N. ABRAMS, INC., NEW YORK (4 refuse Published in conjunction with the exhibition Mappingat The Museum of Modern Art, New York, October 6— tfoti h December 20, 1994, organized by Robert Storr, Curator, Department of Painting and Sculpture The exhibition is supported by AT&TNEW ART/NEW VISIONS. Additional funding is provided by the Contemporary Exhibition Fund of The Museum of Modern Art, established with gifts from Lily Auchincloss, Agnes Gund and Daniel Shapiro, and Mr. and Mrs. Ronald S. Lauder. This publication is supported in part by a grant from The Junior Associates of The Museum of Modern Art. Produced by the Department of Publications The Museum of Modern Art, New York Osa Brown, Director of Publications Edited by Alexandra Bonfante-Warren Designed by Jean Garrett Production by Marc Sapir Printed by Hull Printing Bound by Mueller Trade Bindery Copyright © 1994 by The Museum of Modern Art, New York Certain illustrations are covered by claims to copyright cited in the Photograph Credits. -

I Territori Comunali Dove Ricadono Le Opere Schedate

Montieri Massa Marittima Civitella Paganico Roccastrada Follonica Seggiano Gavorrano Cinigiano Scarlino Campagnatico Arcidosso Santa Fiora Castiglione della Pescaia Grosseto Scansano Sorano Magliano Pitigliano Orbetello Capalbio Monte Argentario Isola del Giglio I territori comunali dove ricadono le opere schedate Impaginato.indd 6 06/12/2011, 8.44 Fondazione Montecucco Edoardo Milesi Presidente del Comitato Culturale Dal 1998 ho lavori in provincia di Grosseto. L’impegno professionale nel settore privato e pubblico è andato via via aumentando convincendomi ben presto a spostare tutta la famiglia e una porzione del mio studio di Bergamo in Toscana. Tra le molte soddisfazioni sicuramente quella di aver trasmesso la passione per l’ambiente e per l’architettura a gran parte dei miei committenti coinvolgendoli nel necessario dibattito su un modo sostenibile di abitare e di costruire nella natura. Sul necessario recupero di un pensiero ecologico inteso come capacità di pensare e progettare in sintonia con la natura, per costruire nell’armonia e Santa Fiora nell’equilibrio dei suoi elementi. Sulla necessità di credere in una architettura contemporanea che sia in grado di interpretare i luoghi e commisurare gli spazi con i comportamenti. Sorano Da due anni questa passione porta la Fondazione Montecucco a finalizzare una consistente parte delle risorse a sua disposizione al dibattito sull’architettura di qualità e il finanziamento di questo libro a Pitigliano pieno titolo ne fa parte. Ho conosciuto gli autori nel 2003 quando fecero visita al costruendo monastero di Siloe. Fu allora che decidemmo che sarebbe stato importante attivare in modo sistematico sul territorio un dibattito non solo sull’architettura, ma anche sulla figura dell’architetto, che non è lo specialista del costruire o della gestione del territorio abitato, bensì dell’abitare. -

Benthic Communities Along a Littoral of the Central Adriatic Sea (Italy)

Benthic communities along a littoral of the Central Adriatic Sea (Italy) Federica Semprucci, Paola Boi, Anita Manti, Anabella Covazzi Harriague, Marco Rocchi, Paolo Colantoni, Stefano Papa, Maria Balsamo To cite this version: Federica Semprucci, Paola Boi, Anita Manti, Anabella Covazzi Harriague, Marco Rocchi, et al.. Ben- thic communities along a littoral of the Central Adriatic Sea (Italy). Helgoland Marine Research, Springer Verlag, 2009, 64 (2), pp.101-115. 10.1007/s10152-009-0171-x. hal-00535205 HAL Id: hal-00535205 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00535205 Submitted on 11 Nov 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Helgol Mar Res (2010) 64:101–115 DOI 10.1007/s10152-009-0171-x ORIGINAL ARTICLE Benthic communities along a littoral of the Central Adriatic Sea (Italy) Federica Semprucci Æ Paola Boi Æ Anita Manti Æ Anabella Covazzi Harriague Æ Marco Rocchi Æ Paolo Colantoni Æ Stefano Papa Æ Maria Balsamo Received: 24 August 2008 / Revised: 7 September 2009 / Accepted: 10 September 2009 / Published online: 22 September 2009 Ó Springer-Verlag and AWI 2009 Abstract Bacteria, meio- and macrofauna were investi- Keywords Bacteria Á Meiofauna Á Macrofauna Á gated at different depths in a coastal area of the Central Adriatic Sea Adriatic Sea, yielding information about the composition and abundance of the benthic community. -

Discovery Marche.Pdf

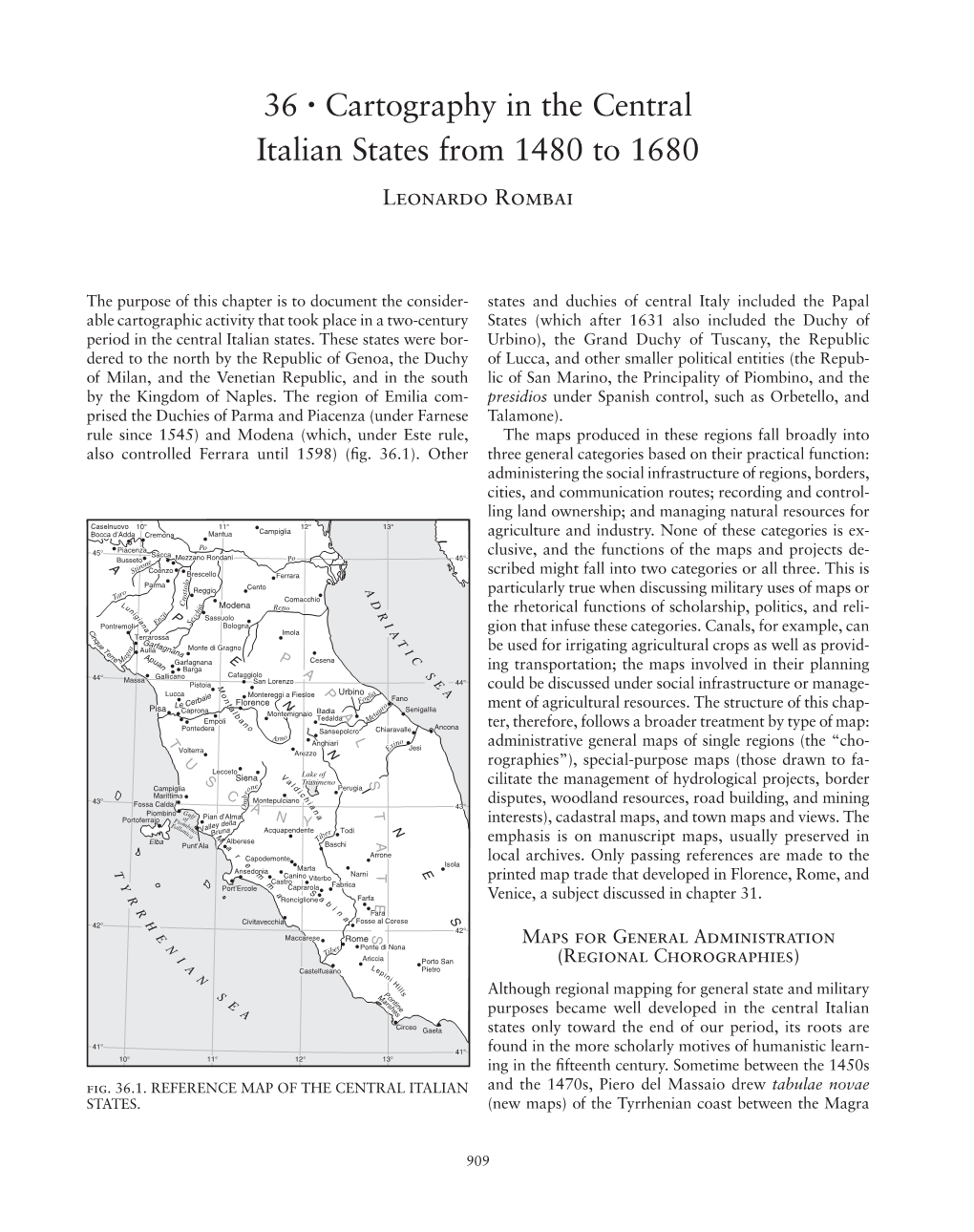

the MARCHE region Discovering VADEMECUM FOR THE TOURIST OF THE THIRD MILLENNIUM Discovering THE MARCHE REGION MARCHE Italy’s Land of Infinite Discovery the MARCHE region “...For me the Marche is the East, the Orient, the sun that comes at dawn, the light in Urbino in Summer...” Discovering Mario Luzi (Poet, 1914-2005) Overlooking the Adriatic Sea in the centre of Italy, with slightly more than a million and a half inhabitants spread among its five provinces of Ancona, the regional seat, Pesaro and Urbino, Macerata, Fermo and Ascoli Piceno, with just one in four of its municipalities containing more than five thousand residents, the Marche, which has always been Italyʼs “Gateway to the East”, is the countryʼs only region with a plural name. Featuring the mountains of the Apennine chain, which gently slope towards the sea along parallel val- leys, the region is set apart by its rare beauty and noteworthy figures such as Giacomo Leopardi, Raphael, Giovan Battista Pergolesi, Gioachino Rossini, Gaspare Spontini, Father Matteo Ricci and Frederick II, all of whom were born here. This guidebook is meant to acquaint tourists of the third millennium with the most important features of our terri- tory, convincing them to come and visit Marche. Discovering the Marche means taking a path in search of beauty; discovering the Marche means getting to know a land of excellence, close at hand and just waiting to be enjoyed. Discovering the Marche means discovering a region where both culture and the environment are very much a part of the Made in Marche brand. 3 GEOGRAPHY On one side the Apen nines, THE CLIMATE od for beach tourism is July on the other the Adriatic The regionʼs climate is as and August.