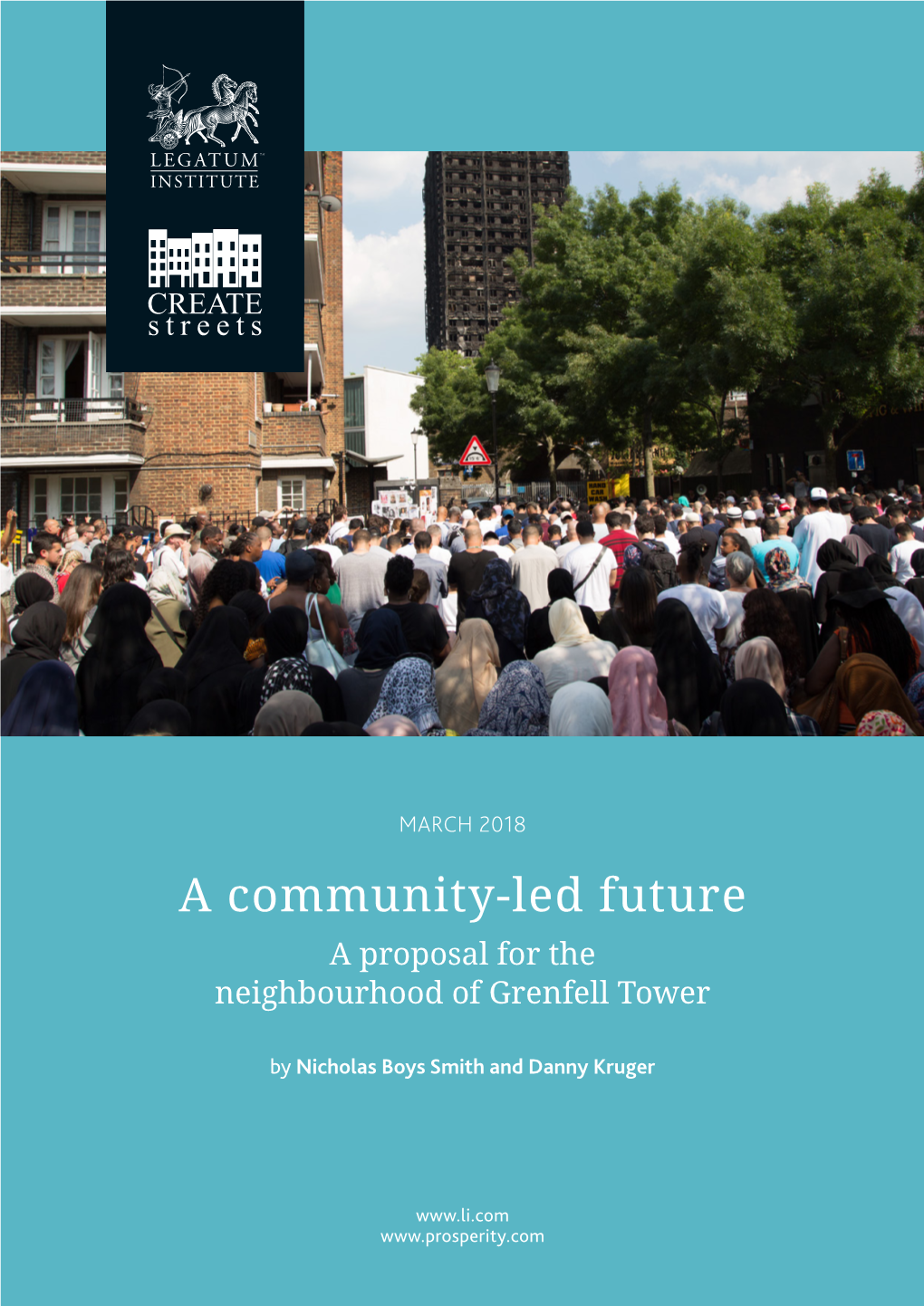

A Community-Led Future a Proposal for the Neighbourhood of Grenfell Tower

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Vision for Social Housing

Building for our future A vision for social housing The final report of Shelter’s commission on the future of social housing Building for our future: a vision for social housing 2 Building for our future: a vision for social housing Contents Contents The final report of Shelter’s commission on the future of social housing For more information on the research that 2 Foreword informs this report, 4 Our commissioners see: Shelter.org.uk/ socialhousing 6 Executive summary Chapter 1 The housing crisis Chapter 2 How have we got here? Some names have been 16 The Grenfell Tower fire: p22 p46 changed to protect the the background to the commission identity of individuals Chapter 1 22 The housing crisis Chapter 2 46 How have we got here? Chapter 3 56 The rise and decline of social housing Chapter 3 The rise and decline of social housing Chapter 4 The consequences of the decline p56 p70 Chapter 4 70 The consequences of the decline Chapter 5 86 Principles for the future of social housing Chapter 6 90 Reforming social renting Chapter 7 Chapter 5 Principles for the future of social housing Chapter 6 Reforming social renting 102 Reforming private renting p86 p90 Chapter 8 112 Building more social housing Recommendations 138 Recommendations Chapter 7 Reforming private renting Chapter 8 Building more social housing Recommendations p102 p112 p138 4 Building for our future: a vision for social housing 5 Building for our future: a vision for social housing Foreword Foreword Foreword Reverend Dr Mike Long, Chair of the commission In January 2018, the housing and homelessness charity For social housing to work as it should, a broad political Shelter brought together sixteen commissioners from consensus is needed. -

Hundreds of Homes for Sale See Pages 3, 4 and 5

Wandsworth Council’s housing newsletter Issue 71 July 2016 www.wandsworth.gov.uk/housingnews Homelife Queen’s birthday Community Housing cheat parties gardens fined £12k page 10 and 11 Page 13 page 20 Hundreds of homes for sale See pages 3, 4 and 5. Gillian secured a role at the new Debenhams in Wandsworth Town Centre Getting Wandsworth people Sarah was matched with a job on Ballymore’s Embassy Gardens into work development in Nine Elms. The council’s Work Match local recruitment team has now helped more than 500 unemployed local people get into work and training – and you could be next! The friendly team can help you shape up your CV, prepare for interview and will match you with a live job or training vacancy which meets your requirements. Work Match Work They can match you with jobs, apprenticeships, work experience placements and training courses leading to full time employment. securing jobs Sheneiqua now works for Wandsworth They recruit for dozens of local employers including shops, Council’s HR department. for local architects, professional services, administration, beauti- cians, engineering companies, construction companies, people supermarkets, security firms, logistics firms and many more besides. Work Match only help Wandsworth residents into work and it’s completely free to use their service. Get in touch today! w. wandsworthworkmatch.org e. [email protected] t. (020) 8871 5191 Marc Evans secured a role at 2 [email protected] Astins Dry Lining AD.1169 (6.16) Welcome to the summer edition of Homelife. Last month, residents across the borough were celebrating the Queen’s 90th (l-r) Cllr Govindia and CE Nick Apetroaie take a glimpse inside the apartments birthday with some marvellous street parties. -

JLTC Playscript

JUST LIKE THE COUNTRY BY JOYCE HOLLIDAY FOR AGE EXCHANGE THEATRE THE ACTION TAKES PLACE, FIRST IN THE CENTRE, AND THEN IN THE OUTSKIRTS, OF LONDON, IN THE MID-NINETEEN TWENTIES. THE SET IS DESIGNED FOR TOURING AND SHOULD BE VERY SIMPLE. IT GIVES THREE DIFFERENT DOUBLE SETS. THE FIRST DOUBLE SET SHOWS, ON ONE SIDE, A SLUM BEDROOM, AND, ON THE OTHER, A PUB INTERIOR. THE SECOND SHOWS TWO VERY SIMILAR COUNCIL HOUSE INTERIORS. THE THIRD SHOWS TWO COUNCIL HOUSE EXTERIORS WITH VERY DIFFERENT GARDENS. THE STAGE FURNITURE IS KEPT TO THE MINIMUM AND CONSISTS OF A SMALL TABLE, ONE UPRIGHT CHAIR, AN ORANGE BOX AND TWO DECKCHAIRS. THE PLAY IS WRITTEN SPECIFICALLY FOR A SMALL TOURING COMPANY OF TWO MEN AND TWO WOMEN, EACH TAKING SEVERAL PARTS. VIOLET, who doubles as Betty FLO, who doubles as Phyllis, Mother, and Edna LEN, who doubles as the Housing Manager, the Builder, and Charlie GEORGE, who doubles as Alf, the Organ Grinder, the Doctor, Mr. Phillips, and Jimmy. THE FIRST DOUBLE SET SHOWS, ON ONE SIDE, A SLUM BEDROOM WITH TWO B TOGETHER. THROUGH THE BROKEN WINDOW, A VIEW OF BRICK WALLS AND ROO IS A REMOVABLE PICTURE HANGING ON A NAIL. THE OTHER SCREEN SHOWS A DINGY BUT PACKED WITH LIVELY PEOPLE. THE ACTORS ENTER FROM THE PUB SIDE, CARRYING GLASSES, ETC. THEY GRE AND THE AUDIENCE INDISCRIMINATELY, MOVING ABOUT A LOT, SPEAKING TIME, USING AND REPEATING THE SAME LINES AS EACH OTHER. GENERA EXCITEMENT. ALL CAST: Hello! Hello there! Hello, love! Watcha, mate! Fancy seeing you! How are you? How're you keeping? I'm alright. -

Historical and Contemporary Archaeologies of Social Housing: Changing Experiences of the Modern and New, 1870 to Present

Historical and contemporary archaeologies of social housing: changing experiences of the modern and new, 1870 to present Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Leicester by Emma Dwyer School of Archaeology and Ancient History University of Leicester 2014 Thesis abstract: Historical and contemporary archaeologies of social housing: changing experiences of the modern and new, 1870 to present Emma Dwyer This thesis has used building recording techniques, documentary research and oral history testimonies to explore how concepts of the modern and new between the 1870s and 1930s shaped the urban built environment, through the study of a particular kind of infrastructure that was developed to meet the needs of expanding cities at this time – social (or municipal) housing – and how social housing was perceived and experienced as a new kind of built environment, by planners, architects, local government and residents. This thesis also addressed how the concepts and priorities of the Victorian and Edwardian periods, and the decisions made by those in authority regarding the form of social housing, continue to shape the urban built environment and impact on the lived experience of social housing today. In order to address this, two research questions were devised: How can changing attitudes and responses to the nature of modern life between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries be seen in the built environment, specifically in the form and use of social housing? Can contradictions between these earlier notions of the modern and new, and our own be seen in the responses of official authority and residents to the built environment? The research questions were applied to three case study areas, three housing estates constructed between 1910 and 1932 in Birmingham, London and Liverpool. -

Birmingham City Council Report to Cabinet 14Th May 2019

Birmingham City Council Report to Cabinet 14th May 2019 Subject: Houses in Multiple Occupation Article 4 Direction Report of: Director, Inclusive Growth Relevant Cabinet Councillor Ian Ward, Leader of the Council Members: Councillor Sharon Thompson, Cabinet Member for Homes and Neighbourhoods Councillor John Cotton, Cabinet Member for Social Inclusion, Community Safety and Equalities Relevant O &S Chair(s): Councillor Penny Holbrook, Housing & Neighbourhoods Report author: Uyen-Phan Han, Planning Policy Manager, Telephone No: 0121 303 2765 Email Address: [email protected] Are specific wards affected? ☒ Yes ☐ No If yes, name(s) of ward(s): All wards Is this a key decision? ☒ Yes ☐ No If relevant, add Forward Plan Reference: 006417/2019 Is the decision eligible for call-in? ☒ Yes ☐ No Does the report contain confidential or exempt information? ☐ Yes ☒ No 1 Executive Summary 1.1 Cabinet approval is sought to authorise the making of a city-wide direction under Article 4 of the Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) (England) Order 2015. This will remove permitted development rights for the change of use of dwelling houses (C3 Use Class) to houses in multiple occupation (C4 Use Class) that can accommodate up to 6 people. 1.2 Cabinet approval is also sought to authorise the cancellation of the Selly Oak, Harborne and Edgbaston Article 4 Direction made under Article 4(1) of the Town and Country Planning (General Permitted Development) (England) Order 1995. This is to avoid duplication as the city-wide Article 4 Direction will cover these areas. Page 1 of 8 2 Recommendations 2.1 That Cabinet authorises the Director, Inclusive Growth to prepare a non- immediate Article 4 direction which will be applied to the City Council’s administrative area to remove permitted development rights for the change of use of dwelling houses (C3 use) to small houses in multiple occupation (C4 use). -

Housebuilder & Developer

Grenfell Tower: The Social Network: Housebuilding sector Industry reaction as Patrick Mooney says offers words of the investigation gets lessons must be encouragement to underway learned from Grenfell new Housing Minister Page 05 Page 20 Page 08 07.17 Housebuilder & Developer A NEW WAY OF LIVING Report predicts £70bn growth in Build to Rent by 2020, with renters benefitting from a much wider range of extra amenities (see Industry News) The sound good factor is here and you can For your customers, this means enjoying build it into every property with Isover every room to the full without the worry acoustic insulation. of noise disturbing anyone else. Use Isover in your next build and see for yourself how This means you can create homes that sound the sound good factor can enhance build as good as they look, while not just passing quality and increase sales. acoustic regulations but surpassing them. Find out about turning sound into sales at soundgoodfactor.co.uk 07.17 CONTENTS 19 25 COMMENT CASE STUDY A CULTURE OF COLLABORATION COULD KODA BE THE ANSWER? As the dust begins to settle after the General A sustainable factory-made modular home has Election, those working in construction have had been launched in partnership with the BRE, an almighty challenge working out just what a which is hoped to provide a new answer to the hung Parliament might mean. growing UK housing crisis. FEATURES: 29 45 AIR CONDITIONING & VENTILATION SOCIAL HOUSING ALSO IN FAST RECOVERY NEW AGE BATHROOMS Martin Passingham of Daikin UK explores how a Martin Walker of Methven UK considers the role THIS ISSUE: 960 mm parapet wall nearly ruined air played by technology and design in the creation conditioning plans for a listed five-storey house of usable bathrooms for the country’s ageing 04-15 in Hyde Park, London. -

Final General Management Plan/Environmental Impact Statement, Mary Mcleod Bethune Council House National Historic Site

Final General Management Plan Environmental Impact Statement Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site Washington, D.C. Final General Management Plan / Environmental Impact Statement _____________________________________________________________________________ Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site Washington, District of Columbia The National Park Service is preparing a general management plan to clearly define a direction for resource preservation and visitor use at the Mary McLeod Bethune Council House National Historic Site for the next 10 to 15 years. A general management plan takes a long-range view and provides a framework for proactive decision making about visitor use, managing the natural and cultural resources at the site, developing the site, and addressing future opportunities and problems. This is the first NPS comprehensive management plan prepared f or the national historic site. As required, this general management plan presents to the public a range of alternatives for managing the site, including a preferred alternative; the management plan also analyzes and presents the resource and socioeconomic impacts or consequences of implementing each of those alternatives the “Environmental Consequences” section of this document. All alternatives propose new interpretive exhibits. Alternative 1, a “no-action” alternative, presents what would happen under a continuation of current management trends and provides a basis for comparing the other alternatives. Al t e r n a t i v e 2 , the preferred alternative, expands interpretation of the house and the life of Bethune, and the archives. It recommends the purchase and rehabilitation of an adjacent row house to provide space for orientation, restrooms, and offices. Moving visitor orientation to an adjacent building would provide additional visitor services while slightly decreasing the impacts of visitors on the historic structure. -

Journey of Recovery Needs Assessment

A Journey of Recovery Supporting health & wellbeing for the communities impacted by the Grenfell Tower fire disaster This report This report The report considers the primary impacts on the health and wellbeing of those affected by the Grenfell disaster, and makes a number of recommendations to support the journey to recovery. In doing so, it has attempted to draw on a range of evidence and insights, to help those involved with recovery at any level in the work they are doing. It brings together evidence about: ñ The characteristics of the communities prior to the fire. ñ Evidence from the impact of other disasters both from the UK and internationally to learn from the experience of elsewhere. ñ Analysis of data on the impact of Grenfell one year one to try and understand both the nature and scale of the impact. ñ The voice of people in the community on what matters most to those who have been affected and what is important in recovery to them. Report authors and contributors Jason Strelitz, Chris Lawrence, Clare Lyons-Amos, Tammy Macey Acknowledgements We would like to thank all the residents and those working across North Kensington who have contributed to this report in many ways, and in particular to Natasha Elcock and Bilal Elguenuni from Grenfell United for sharing their insights and reflections. We would also like to thank many colleagues in Kensington and Chelsea Council, West London Clinical Commissioning Group and Central and North West London (CNWL) NHS Foundation Trust who have helped developed this report. Thank you also to Shane Ryan from Working with Men, for his support in reaching out to young people to inform this work, Rajaa Bouchab and Hamza Taouzzale who led the young people’s peer research project, and William Degraft Johnson and Tayshan Hayden Smith, who carried out the interviews for the boys and young men research. -

Birmingham City Council City Council a G E N

BIRMINGHAM CITY COUNCIL CITY COUNCIL TUESDAY, 10 JULY 2018 AT 14:00 HOURS IN COUNCIL CHAMBER, COUNCIL HOUSE, VICTORIA SQUARE, BIRMINGHAM, B1 1BB A G E N D A 1 NOTICE OF RECORDING Lord Mayor to advise that this meeting will be webcast for live or subsequent broadcast via the Council's Internet site (www.civico.net/birmingham) and that members of the press/public may record and take photographs except where there are confidential or exempt items. 2 DECLARATIONS OF INTERESTS Members are reminded that they must declare all relevant pecuniary and non pecuniary interests arising from any business to be discussed at this meeting. If a disclosable pecuniary interest is declared a Member must not speak or take part in that agenda item. Any declarations will be recorded in the minutes of the meeting. 3 MINUTES 5 - 86 To confirm and authorise the signing of the Minutes of the meeting of the Council held on 12 June 2018. 4 LORD MAYOR'S ANNOUNCEMENTS (1400-1410) To receive the Lord Mayor's announcements and such communications as the Lord Mayor may wish to place before the Council. 5 PETITIONS (15 minutes allocated) (1410-1425) To receive and deal with petitions in accordance with Standing Order 9. As agreed by Council Business Management Committee a schedule of outstanding petitions is available electronically with the published papers for the meeting and can be viewed or downloaded. Page 1 of 118 6 QUESTION TIME (90 minutes allocated) (1425-1555) To deal with oral questions in accordance with Standing Order 10.3 A. -

Bromley Borough Guide the Drive for Excellence in Management

THE LONDON BOROUGH f floor central 1, library, high street, bromley br1 1ex answering arts »halls your sports • zoos leisure nature trails »parks information holiday activities needs museums »libraries Leisureline THE LONDON BOROUGH L A creative service that is designed to understand problems and provide lasting solutions. t o liter a to c o rp o rate i d e n t it y 1. e/ H I If I 4 0 1 r r l j m ¡têt* vdu WORKER creative consultants has the right idea Rushmore 55 Tweedy Road, Bromley, Kent BRI 3NH Telephone 081-464 6380/6389 Fax 081-290 1053 YOUNGS FENCING IS OUR BUSINESS! looking for new fencing?, or advice how to fix the old one?, ... perhaps a new shed!! “THEN COME TO THE REAL EXPERTS”, whatever the problem, we’re sure we can solve it. TRAINED & EXPERIENCED SALES S T A F F > ^ ^ WAITING TO HELP YOU! AND AS A BONUS Mon-Fri 8 am-12.30 pm With our new Celbronze plant we can now provide all our fencing 1.30 pm-5.30 pm and sheds in a rich walnut shade, with the added bonus of pressure Sat 8 am-5 pm treated wood guaranteed for long life and with the backing of Rentokil expertise. SHEDS 10 DESIGNS FENCING SIZES TO YOUR ALL TYPES SPECIFICATION SUPPLY ONLY: FREE AND PROMPT DELIVERY SUPPLY AND ERECT: INSPECTIONS AND ESTIMATES FREE SEVENOAKS WAY, ST PAULS CRAY (NEXT TO TEXAS HOMECARE) ORPINGTON (0689) 826641 (5 LINES) FAX (0689) 878343 2 The Bromley Borough Guide The Drive for Excellence in Management ia— Bntish TELECOM A«» u It,.......a ‘.A. -

Westminster, St. James's, Belgravia, Mayfair

Map of Public T ransport Connections in Westminster, St. James’s, Belgravia & Mayfair including Charing Cross, V ictoria & Victoria Coach Stations (click on bus/coach route numbers / train line labels for timetable information) This map does not show Use the Adobe Reader “Find” function to coach/commuter routes. search for streets, stations, places and bus routes “New Bus for London” last updated August 2021 are in service on Routes 3, 8, 9, 1 1, 12, 15, 16, 19, 21, 24, 27, 38, 55, 59, 68, 73, 76, 87, 91, 137, 148, 149, 159, 168, 176, 189, 21 1, 253, 254, 267, 313, 390, 453, EL1, EL2, EL3 6 Aldwych 12 Oxford Circus Margaret Street Fully electric buses in London on routes: 9 Aldwych Oxford Circus, Camden Town, 7, 23, 43, 46, 49*, 63*, 65*, 69, 70, 94, 100, 106, 1 11*, 125*, 132*,Aldwych, 134, St. 153, Paul’ s, Bank, 88 Kentish Town, Parliament Hill Fields 11 160*, 173, 174, 180*, 183*, 184, 200, 204*, 212, 214, 230, 235*, 281*, 290*, Moorgate Eldon Street 94 Oxford Circus, Marble Arch, Notting Hill, Aldwych, St. Paul’s, Tower Gateway, Shepherd’s Bush, Acton Green South Parade 15 Aldgate, Limehouse, Poplar, Blackwall Station Oxford Circus, Marylebone, St. John’s Wood, 312, 319*, 323, 357, 358*, 360, 371*, 398*, 444, 484, 507, 521, 660*, 139 West Hampstead, Golders Green 692, 699, C1, C3, C10, H9*, H10*, P5, U5*, W15*, X140*, N7*, N65* 87 Aldwych 159 Oxford Circus * indicates conversion to electric buses during 2021/22 Holborn, Euston, King’s Cross, Holloway, 91 Hornsey Rise, Crouch End Elmfield Avenue 453 Oxford Circus, Marylebone Station 139 Aldwych, Waterloo Station Tottenham Court Road, Camden Town, Aldwych, Waterloo, Camberwell Green, N3 Oxford Circus Harewood Place 24 Chalk Farm, Hampstead Heath South End Green 176 East Dulwich, Forest Hill, Penge Pawleyne Arms Tottenham Court Road, Tottenham Ct. -

W2 2014 London Market Focus

RESIDENTIAL RESEARCH W2 2014 LONDON MARKET FOCUS DEVELOPMENT POTENTIAL HOTEL TO RESIDENTIAL QUEENSWAY OUTPERFORMS NORTH OF HYDE PARK CONVERSION OPPORTUNITIES PRIME CENTRAL LONDON KEY FINDINGS THE RIGHT SIDE W2 has strong potential for OF THE PARK price growth and offers better Bordered by Hyde Park, Notting Hill, Maida Vale and value than other postcodes the Hyde Park Estate and to be served by a major adjoining Hyde Park. Price growth in other postcodes Crossrail station, W2 has arguably the strongest neighbouring the park exceeded development and regeneration potential of any prime the increase in W2 by an average of 27% in the decade to June central London residential market, says Tom Bill. 2014 Some of the most expensive residential It sits between the established prime Prices for the best new-build property in the world surrounds London’s residential markets of Notting Hill in the west schemes are likely to range Hyde Park. and the Hyde Park Estate in the east. Growth in both areas has outperformed the prime between £2,000 and £2,500 per The 625-acre area of green space is the central London average in the last two years square foot, and in some cases epicentre of the prime central London as buyers seek more value away from markets exceed £3,000 per square foot residential market and properties located further south like Kensington and Belgravia, close to the park can achieve large premiums. which experienced strong growth during the Low risk of oversupply, with While many of London’s globally renowned financial crisis due to their ‘safe haven’ appeal.