Origin and Development of Denotified Communities in Tamil Nadu - a Study of Pranmalai Kallars: a Re-Look

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

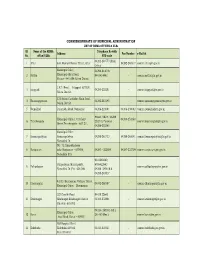

LIST of RDMA OFFICES & Ulbs

COMMISSIONERATE OF MUNICIPAL ADMINISTRATION LIST OF RDMA OFFICES & ULBs Sl. Name of the RDMA Telephone No with Address Fax Number e-Mail id No. office/ULBs STD code 04282-240773 (Main 1 Attur 634, Ranipet Bazaar Street, Attur 04282-240317 [email protected] Office) Municipal Office, 04298-244018, 2 Mettur Municipal office Road, 9443414443 - [email protected] Mettur – 641 604,Salem District J.K.P. Road, Idappadi-637101, 3 Idappadi 04283-222201 - [email protected] Salem District. 121 Salem Cuddalore Main Road, 4 Narasingapuram 04282-281495 - [email protected] Salem District 5 Namakkal Paramathi Road, Namakkal 04286-221001 04286-230002 [email protected] Phone: Office : 04288 Municipal Office,1, Cutchery 04288-252360 6 Tiruchengode 252310, Personal : [email protected] Street,Tiruchengode - 637 211, 04288-252360 Municipal Office 7 Komarapalayam Komarapalayam 04288-261733 04288-261041 [email protected] Namakkal Dt. NO. 72, Bharathidasan 8 Rasipuram salai,Rasipuram - 637408, 04287 – 222859 04287-222709 [email protected] Namakkal (Dt) 9444289849, Pallipalayam Municipality, 9789422842 9 Pallipalayam - [email protected] Namakkal Dt.,Pin : 638 006 04288- 240816 & 04288-240817 43/13, Kandasamy Vathiyar Street, 10 Dharmapuri 04342-260387 - [email protected] Municipal Office, Dharmapuri 327 Gandhi Road 94439 22640 11 Krishnagiri Krishnagiri.Krishnagiri District. 04343-232664 - [email protected] Pin code -635 001 04324- 260341 (Off.) Municipal Office, 12 Karur 261480 (Res.) - [email protected] Azad Road, Karur – 639001 Old Hospital Street 13 Kulithalai Kulithalai-639104 04323-222321 - [email protected] Karur District 14 Theni-Allinagaram Theni-Allinagaram Municipal 04546-252470 -- [email protected] Office, Nehruji Road, Theni Allinagaram - 625 531. -

District Survey Report of Madurai District

Content 1.0 Preamble ................................................................................................................. 1 2.0 Introduction .............................................................................................................. 1 2.1 Location ............................................................................................................ 2 3.0 Overview of Mining Activity In The District .............................................................. 3 4.0 List of Mining Leases details ................................................................................... 5 5.0 Details of the Royalty or Revenue received in last Three Years ............................ 36 6.0 Details of Production of Sand or Bajri Or Minor Minerals In Last Three Years ..... 36 7.0 Process of deposition of Sediments In The River of The District ........................... 36 8.0 General Profile of Maduari District ....................................................................... 27 8.1 History ............................................................................................................. 28 8.2 Geography ....................................................................................................... 28 8.3 Taluk ................................................................................................................ 28 8.2 Blocks .............................................................................................................. 29 9.0 Land Utilization Pattern In The -

South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal , Free-Standing Articles Madurai Formula Films: Caste Pride and Politics in Tamil Cinema 2

Edinburgh Research Explorer Madurai Formula Films Citation for published version: Damodaran, K & Gorringe, H 2017, 'Madurai Formula Films', South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal (SAMAJ), pp. 1-30. <https://samaj.revues.org/4359> Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal (SAMAJ) General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 28. Sep. 2021 South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal Free-Standing Articles Madurai Formula Films: Caste Pride and Politics in Tamil Cinema Karthikeyan Damodaran and Hugo Gorringe Publisher Association pour la recherche sur l'Asie du Sud (ARAS) Electronic version URL: http://samaj.revues.org/4359 ISSN: 1960-6060 Electronic reference Karthikeyan Damodaran and Hugo Gorringe, « Madurai Formula Films: Caste Pride and Politics in Tamil Cinema », South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal [Online], Free-Standing Articles, Online since 22 June 2017, connection on 22 June 2017. URL : http://samaj.revues.org/4359 This text was automatically generated on 22 June 2017. -

SNO APP.No Name Contact Address Reason 1 AP-1 K

SNO APP.No Name Contact Address Reason 1 AP-1 K. Pandeeswaran No.2/545, Then Colony, Vilampatti Post, Intercaste Marriage certificate not enclosed Sivakasi, Virudhunagar – 626 124 2 AP-2 P. Karthigai Selvi No.2/545, Then Colony, Vilampatti Post, Only one ID proof attached. Sivakasi, Virudhunagar – 626 124 3 AP-8 N. Esakkiappan No.37/45E, Nandhagopalapuram, Above age Thoothukudi – 628 002. 4 AP-25 M. Dinesh No.4/133, Kothamalai Road,Vadaku Only one ID proof attached. Street,Vadugam Post,Rasipuram Taluk, Namakkal – 637 407. 5 AP-26 K. Venkatesh No.4/47, Kettupatti, Only one ID proof attached. Dokkupodhanahalli, Dharmapuri – 636 807. 6 AP-28 P. Manipandi 1stStreet, 24thWard, Self attestation not found in the enclosures Sivaji Nagar, and photo Theni – 625 531. 7 AP-49 K. Sobanbabu No.10/4, T.K.Garden, 3rdStreet, Korukkupet, Self attestation not found in the enclosures Chennai – 600 021. and photo 8 AP-58 S. Barkavi No.168, Sivaji Nagar, Veerampattinam, Community Certificate Wrongly enclosed Pondicherry – 605 007. 9 AP-60 V.A.Kishor Kumar No.19, Thilagar nagar, Ist st, Kaladipet, Only one ID proof attached. Thiruvottiyur, Chennai -600 019 10 AP-61 D.Anbalagan No.8/171, Church Street, Only one ID proof attached. Komathimuthupuram Post, Panaiyoor(via) Changarankovil Taluk, Tirunelveli, 627 761. 11 AP-64 S. Arun kannan No. 15D, Poonga Nagar, Kaladipet, Only one ID proof attached. Thiruvottiyur, Ch – 600 019 12 AP-69 K. Lavanya Priyadharshini No, 35, A Block, Nochi Nagar, Mylapore, Only one ID proof attached. Chennai – 600 004 13 AP-70 G. -

Golden Research Thoughts

GRT Golden ReseaRch ThouGhTs ISSN: 2231-5063 Impact Factor : 4.6052 (UIF) Volume - 6 | Issue - 7 | January – 2017 ___________________________________________________________________________________ RAMANATHAPURAM : PAST AND PRESENT- A BIRD’S EYE VIEW Dr. A. Vadivel Department of History , Presidency College , Chennai , Tamil Nadu. ABSTRACT The present paper is an attempt to focus the physical features, present position and past history of the Ramnad District which was formed in the tail end of the Eighteenth Century. No doubt, the Ramnad District is the oldest district among the districts of the erstwhile Madras Presidency and the present Tamil Nadu. The District was formed by the British with the aim to suppress the southern poligars of the Tamil Country . For a while the southern poligars were rebellious against the expansion of the British hegemony in the south Tamil Country. After the formation of the Madras Presidency , this district became one of its districts. For sometimes it was merged with Madurai District and again its collectorate was formed in 1910. In the independent Tamil Nadu, it was trifurcated into Ramnad, Sivagangai and Viudhunagar districts. The district is, historically, a unique in many ways in the past and present. It was a war-torn region in the Eighteenth Century and famine affected region in the Nineteenth Century, and a region known for the rule of Setupathis. Many freedom fighters emerged in this district and contributed much for the growth of the spirit of nationalism. KEY WORDS : Ramanathapuram, Ramnad, District, Maravas, Setupathi, British Subsidiary System, Doctrine of Lapse ,Dalhousie, Poligars. INTRODUCTION :i Situated in the south east corner of Tamil Nadu State, Ramanathapuram District is highly drought prone and most backward in development. -

Khadi Institution Profile Khadi and Village Industries Comission

KHADI AND VILLAGE INDUSTRIES COMISSION KHADI INSTITUTION PROFILE Office Name : SO CHENNAI TAMIL NADU Institution Code : 99027 Institution Name : TAMIL NADU KHADI & V. I. BOARD, Address: : KURALAGAM ANNEXE, 5TH FLOOR, Post : Chennai City/Village : Chennai Pincode : 600104 State : TAMIL NADU District : CHENNAI Aided by : KVIB District : A+ Contact Person Name Email ID Mobile No. Chairman : L.K.TIRUPATHY [email protected] 9566012097 Secretary : Nodal Officer : Registration Detail Registration Date Registration No. Registration Type 12-11-2020 99027 SOC Khadi Certificate No. TND/1254 Date : 31-MAR_2021 Khadi Mark No. 0068 Khadi Mark Dt. 01-Oct-2019 Sales Outlet Details Type Name Address City Pincode Sales Outlet KHADI KRAFT SHANMUGAR SALAI MADRAS 600045 ROAD ,TAMBARAM Sales Outlet KHADI KRAFT NORTH PARK AMBATTUR 600052 STREET , AMBATTUR Sales Outlet GRAMSHILPA KURUUNJIPADI, LUDDALORE 607302 NO.11, BUS STAND Sales Outlet KHADI KRAFT 99/ ERODE MAIN TIRUCHCHIRAPPAL 639104 ROAD, LI Sales Outlet KHADI KRAFT THOTHIYAM, THOTHIYAM 621215 TIRUCHCHIRAPPAL LI Sales Outlet KHADI KRAFT NO-294, K H ROAD AYANAVARM 600023 Sales Outlet KHADI KRAFT NO-173 G A ROAD, CHENNAI 600021 Sales Outlet KHADI KRAFT A D2 BLUE STAR, ANNANAGAR 600040 ANNA NAGAR Sales Outlet KHADI KRAFT 172, ANNASALAI ANNA SALAI 600002 Sales Outlet KHADI KRAFT THIRAVATTIYAR, CHENNAI 600019 Sales Outlet KHADI KRAFT NO-9 ESPLANADE, PARRYS 600001 KURALAGAM Sales Outlet DEPARTMENTAL UNIT OF 26,27 BROTHESTER NAZARATH 600018 KVIB STREET Sales Outlet KHADI KRAFT NO-9 ESPLANADE, PARRYS 600001 KURALAGAM 01 October 2021 Page 1 of 7 Sales Outlet KHADI KRAFT MYLAPORE CHENNAI 600028 ROAD,CHENNAI Sales Outlet DEPARTMENTAL UNIT OF 26,27 BROTHESTER NAZARATH 628617 KVIB STREET Sales Outlet KHADI KRAFT PALANI MAIN ROAD KHADI KRAFT UDU, 642204 , UDUMALPET PALANI M Sales Outlet KHADI KRAFT KUMAR NAGAR , THATTI POLYAM 676103 TIRYAR Sales Outlet KHADI KRAFT PENNAGARAM DHARMAPURI 63670 ROAD , Sales Outlet KHADI KRAFT 7/95, M.G. -

Thiruchirappal Disaster Managem Iruchirappalli

Tiruchirappalli District Disaster Management Plan – 2020 THIRUCHIRAPPALLI DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN-2020 Tiruchirappalli District Disaster Management Plan – 2020 INDEX S. Particulars Page No. No. 1. Introduction 1 2. District Profile 2-4 3. Disaster Management Goals (2017-2030) 5-11 4. Hazard, Risk and Vulnerability Analysis with Maps 12-49 (District map, Division maps, Taluk maps & list of Vulnerable area) 5. Institutional Mechanism 50-52 6. Preparedness Measures 53-56 7. Prevention and Mitigation measures (2015 – 2030) 57-58 8. Response Plan 59 9. Recovery and Reconstruction Plan 60-61 10. Mainstreaming Disaster Management in Development Plans 62-63 11. Community and other Stake holder participation 64-65 12. Linkages / Co-ordination with other agencies for Disaster Management 66 13. Budget and Other Financial allocation – Outlays of major schemes 67 14. Monitoring and Evaluation 68 15. Risk Communication Strategies 69-70 16. Important Contact Numbers and provision for link to detailed information 71-108 (All Line Department, BDO, EO, VAO’s) 17. Dos and Don’ts during all possible Hazards 109-115 18. Important Government Orders 116-117 19. Linkages with Indian Disaster Resource Network 118 20 Vulnerable Groups details 118 21. Mock Drill Schedules 119 22. Date of approval of DDMP by DDMA 120 23. Annexure 1 – 14 120-148 Tiruchirappalli District Disaster Management Plan – 2020 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS S. Abbreviation Explanation No. 1. AO Agriculture Officer 2 AF Armed Forces 3 BDO Block Development Officers 4 DDMA District Disaster Management Authority 5 DDMP District Disaster Management Plan 6 DEOC District Emergency Operations Center 7 DRR Disaster Risk Reduction 8 DERAC District Emergency Relief Advisory Committee. -

Government of Tamilnadu Tamilnadu Irrigated

GOVERNMENT OF TAMILNADU TAMILNADU IRRIGATED AGRICULTURE MODERNISATION AND WATER BODIES RESTORATION AND MANAGEMENT PROJECT (TN – IAMWARM) PROCUREMENT OF WORKS BIDDING DOCUMENT 02/IAMWARM/WRD/TKR/Addl.Schemes/Works/2013-2014 REHABILITATION OF LEFTOUT LINING OF BRANCH CANAL IV & V OF THIRUMANGALAM MAIN CANAL IN THERKKAR SUB BASIN IN USILAMPATTI TALUK OF MADURAI DISTRICT TAMIL NADU – SOUTH INDIA. GOVERNMENT OF TAMILNADU TAMILNADU IRRIGATED AGRICULTURE MODERNISATION AND WATER BODIES RESTORATION AND MANAGEMENT PROJECT (TN – IAMWARM) PROCUREMENT OF WORKS BIDDING DOCUMENT 02/IAMWARM/WRD/TKR/Addl.Schemes/Works/2013-2014 REHABILITATION OF LEFTOUT LINING OF BRANCH CANAL IV & V OF THIRUMANGALAM MAIN CANAL IN THERKKAR SUB BASIN IN USILAMPATTI TALUK OF MADURAI DISTRICT TAMIL NADU - SOUTH INDIA Issue to …………………………………………………………………………………….. …………………………………………………………………………………….. ……………………………………………………………………………………… Superintending Engineer, PWD, Periyar Vaigai Basin Circle, WRD, Madurai. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU TAMIL NADU IRRIGATED AGRICULTURE MODERNISATION AND WATER BODIES RESTORATION AND MANAGEMENT PROJECT (TN IAMWARM) AGREEMENT NO LOAN-4846-IN AND CREDIT – 4255 NATIONAL COMPETITIVE BIDDING (CIVIL WORKS) NAME OF WORK : REHABILITATION OF LEFTOUT LINING OF BRANCH CANAL IV & V OF THIRUMANGALAM MAIN CANAL IN THERKKAR SUB BASIN IN USILAMPATTI TALUK OF MADURAI DISTRICT PERIOD OF SALE OF : FROM 29.11.2013 TO 30.12.2013 BIDDING DOCUMENT TIME AND DATE OF : DATE 19.12.2013 - 11.00 HOURS IST PRE-BID CONFERENCE LAST DATE AND TIME FOR : DATE 31.12.2013 TIME 15.00 HOURS IST RECEIPT OF BIDS TIME AND DATE OF OPENING : DATE 31.12.2013 TIME 15.30 HOURS IST OF BIDS PLACE OF OPENING OF BIDS : Office of the Superintending Engineer, PWD, Periyar Vaigai Basin Circle, Madurai 625 001. -

Tamil Nadu Government Gazette

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2012-14. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2013 [Price: Rs. 27.20 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 10] CHENNAI, WEDNESDAY, MARCH 13, 2013 Maasi 29, Nandhana, Thiruvalluvar Aandu–2044 Part VI—Section 4 Advertisements by private individuals and private institutions CONTENTS PRIVATE ADVERTISEMENTS Pages Change of Names .. 553-619 Notice .. 620 NOTICE NO LEGAL RESPONSIBILITY IS ACCEPTED FOR THE PUBLICATION OF ADVERTISEMENTS REGARDING CHANGE OF NAME IN THE TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE. PERSONS NOTIFYING THE CHANGES WILL REMAIN SOLELY RESPONSIBLE FOR THE LEGAL CONSEQUENCES AND ALSO FOR ANY OTHER MISREPRESENTATION, ETC. (By Order) Director of Stationery and Printing. CHANGE OF NAMES 8416. I, Barakathu Nisha, wife of Thiru Syed Ahamed 8419. My son, P. Jayakodi, born on 10th October 2010 Kabeer, born on 1st April 1966 (native district: (native district: Virudhunagar), residing at Old No. 8-23, New Ramanathapuram), residing at Old No. 4-66, New No. 4/192, No. 8-99, West Street, Veeranapuram, Kalingapatti, Chittarkottai Post, Ramanathapuram-623 513, shall henceforth Sankarankoil Taluk, Tirunelveli-627 753, shall henceforth be be known as BARAKATH NEESHA. known as V.P. RAJA. BARAKATHU NISHA. M. PERUMALSAMY. Ramanathapuram, 4th March 2013. Tirunelveli, 4th March 2013. (Father.) 8420. I, Sarika Kantilal Rathod, wife of Thiru Shripal, born 8417. I, S Rasia Begam, wife of Thiru M. Sulthan, born on on 3rd February 1977 (native district: Chennai), residing at 2nd June 1973 (native district: Dindigul), residing at Old No. 140-13, Periyasamy Road, R.S. Puram Post, Coimbatore- No. 4/115-E, New No. -

Assessment of Fluoride Contaminations in Groundwater of Hard Rock

Appl Water Sci DOI 10.1007/s13201-015-0312-0 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Assessment of fluoride contaminations in groundwater of hard rock aquifers in Madurai district, Tamil Nadu (India) 1 1 2 1 3 C. Thivya • S. Chidambaram • M. S. Rao • R. Thilagavathi • M. V. Prasanna • S. Manikandan1 Received: 19 February 2015 / Accepted: 7 July 2015 Ó The Author(s) 2015. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract The fluoride contamination in drinking water is fluoride bearing minerals in groundwater. The higher already gone to the alarming level and it needs the concentration of fluoride ions are observed in the lower EC immediate involvement and attention of all people to solve concentration. The isotopic study suggests that fluoride is this problem. Fluoride problem is higher in hard rock ter- geogenic in nature. In factor scores, fluoride is noted in rains in worldwide and Madurai is such type of hard rock association with pH which indicates the dissolution region. Totally 54 samples were collected from the process. Madurai district of Tamilnadu with respect to lithology. The samples collected were analysed for major cations and Keywords Groundwater Á Fluoride Á Lithology Á anions using standard procedures. The higher concentration Weathering of fluoride is noted in the Charnockite rock types of northern part of the study area. 20 % of samples are below 0.5 ppm and 6 % of samples are above 1.5 ppm exceeding Introduction the permissible limit. The affinity between the pH and fluoride ions in groundwater suggests that dissolution of The highly reactive fluorine exists in the form of fluoride in natural waters (Leung and Hrudey 1985). -

Prefix Gpfno Name 06/96 04/98 09/13 07/03 02/12 04/93 01/15 08/10 11/91 11/09 03/99 09/91 07/91 09/92 07/91 10/91 03/97 05/13 01

Subscribers with one or two missing credits upto February 2015 18-JAN-21 05:32 PM (Press Ctrl+F and type your gpf number to identify your record in this list) Send recovery amount of subs/refund and month of encashment for clearance of missing credit(s) PREFIX GPFNO NAME DRAWING AND DISBURSING OFFICER MISSING MONTHS AGRI 23136 SENTHIL M SUPDT ENGR AE)LAND DEVELOPMENT O/O THE CHIEF ENGR(AE) CH 35 06/96 , 27131 JOHN DURAIRAJ S ADMN OFFICER O\O THE JOINT DIR OF AGRICULTURE TIRUVALLUR 04/98 , 09/13 , 27365 BALAN S DY DIR OF AGRI WATER MGT TRAINING CENTRE VINAYAGAPURAM MDU 07/03 , 28080 PARTHIBAN K ASST DIR OF AGRI SARKARSAMAKULAM COIMBATORE DIST 02/12 , 28216 AGALYASAMUNDESWARI C JOINT DIRECTOR OF AGRI COIMBATORE 04/93 , 28244 SELVARAJU S ASST DIR OF AGRI PAVINJUR KANCHEEPURAM DIST 01/15 , 08/10 , 28620 VINAYAGAMOORTHY K ASST DIR OF AGRI RAJAPALAYAM 11/91 , 28651 MOHAN DOSS M ASST EXE ENGR (AE) TANJORE 11/09 , 28748 RAVICHANDAR A K ASST EXE ENGR (AE) KUMBAKONAM 03/99 , 09/91 , 28820 MANI R ASST DIR OF AGRI MELBHUVANAGIRI CUDDALORE DIST 07/91 , 09/92 , 28832 BALASUBRAMANIAN T ASST DIR OF AGRI VALANGAIMAN TIRUVARUR 07/91 , 10/91 , 28957 EMMANUEL RAJAA D DY DIR OF AGRI PA TO COLLECTOR (AGRI) COIMBATORE 03/97 , 05/13 , 28960 SAMPATH KUMAR V ADMN OFFICER DIR OF AGRL CHEPAUK CHENNAI - 5 01/95 , 11/91 , 29126 CHANDRANAGAR T DY DIR OF AGRI (AGRI BUSINESS) VIRUDHUNAGAR 11/91 , 29258 RAMASWAMY K ASST EXE ENGR (AE) KRISHNAGIRI 05/93 , 29317 DEVARAJ I ASST EXE ENGR AGRL ENGINEERAING DEPT UDUMALPET TIRUPPUR DIST 09/00 , 29447 KUMARASAMI D DY DIR OF AGRI -

Madurai District 12 5

Page Chapter Content No. 1. Introduction 1 2. Overview of Mining Activity in the District 4 3. General Profile of the District 6 4. Geology of Madurai District 12 5. Drainage of Irrigation pattern 17 Land Utilisation Pattern in the District: Forest, Agricultural, 6. 18 Horticultural, Mining etc., 7. Surface Water and Ground Water scenario of the District 20 8. Climate and Rainfall of the District 21 9. Details of Mining Leases in the District 23 10. Details of Royalty or Revenue received in last three years 28 11. Details of Production of Minor Mineral in last three years 29 12. Mineral Map of the District 30 List of Letter of Intent (LOI) Holder in the District along with 13. 31 its validity 14. Total Mineral Reserve available in the district 32 15. Quality/Grade of Mineral available in the district 33 16. Use of Mineral 34 17. Demand and supply of the Mineral in the last three years 34 18. Mining Leases marked on the map of the district 35 Details of the area of where there is a cluster of the mining 19. 36 leases 20. Details of Eco-sensitive area 36 21. Impact on the environment due to Mining activity 37 Remedial measures to mitigate the impact of mining on the 22. 38 environment 23. Reclamation of the mined out area 39 24. Risk assessment & Disaster Management Plan 39 25. Details of Occupational health issue in the District 41 Plantation and Green belt development in respect of leases 26. 41 already granted in the district 27. Any other information 42 LIST OF PLATES Plate 1.