Four Days in September 11-09-2001

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MAP01-T-2 – Airspace Classifications

MAPT01-T-1 - Airspace Classification Systems This document contains information and suggestions that while not mandatory are never-the-less important advice for all MAAC members. To ensure that you have the latest version always check the MAAC Web Site. 1.0 Title. MAP01 - Tutorial 2 (MAP01-T-2) – Airspace Classification Systems 2.0 Purpose. To provide MAAC Clubs and members an expanded plain language guide on the North American Airspace Classification system. This information is essential for members who are not familiar with the aviation system as they navigate the new regulatory realities. 3.0 Definitions Glossary of Terms. The following new definitions were added to as they are related specifically to this topic. References, expansion and examples of meaning will be provided in the text of this document. NONE 4.0 Contents The following topics will inform a MAAC member on the relevant parts of the North American Airspace system needed to comply with the exemption: A. Overview of North American Air Space • NAV CANADA and its basic structure • FAA and its role with Canadian Airspace • Other “controlling agencies” B. Relevant parts of the Canadian Airspace system • Airspace types and classifications • Controlled Airports & Aerodromes & Airspace • Alert and Restricted Airspace C. General Aviation concepts MAAC members need to know: • ACC versus Tower • IFR versus VFR Page 1 of 11 Airspace Classification Tutorial, MAP01-T-2 ver 1 This is an uncontrolled copy when printed, June 29, 2020 MAPT01-T-1 - Airspace Classification Systems A. Overview of North American Air Space One big picture distinction a MAAC member should know is who owns what and who controls whom – how does the aviation system work? In layman’s terms the hierarchy is as follows: 1. -

NAV CANADA and DATA LINK IMPLEMENTATION

NAV CANADA and DATA LINK IMPLEMENTATION Shelley Bailey NAV CANADA May 2016 – Sint Maarten OPDWLG – Operational Data Link Working Group • 5 members here today representing ANSPs, manufacturers and regulators • Small representation of a multi-disciplinary group made up of such groups as, human factors specialists, regulators, aircraft systems specialists, air carriers, pilots, and controllers. • Make recommendations on operational datalink to the ANC. About NAV CANADA • Private, non-share capital company • 18 million square km of airspace • 2nd largest ANSP in the world • Regulated by Federal Government • 12 million aircraft movements on safety performance annually 3 Our People 4,600 employees across the country • Air Traffic Controllers • Engineering and IM • Flight Service Specialists • Corporate Functions • Electronics Technologists 4 Canadian Airspace Characteristics • Vast distances • Busiest oceanic airspace • Climate varies from polar in the world to temperate • Unique northern airspace operations • Crossroads of global air traffic flows • Stimulus for innovation 5 6 System Progress Investment $2 billion in new technology and facilities since 1996. 7 DATA LINK IN CANADA • OCEANIC SERVICES • DOMESTIC SERVICE • TOWERS 8 Gander Oceanic Controls between 1400-1600 transatlantic flights per day Two primary traffic flows Eastbound – catches the winds of the Jetstream Westbound – avoid the Jetstream winds First data link services to a FANS1/A aircraft was in 2001 Introduced the NAT Data Link Mandate in 2013 Now using 3 data link based -

600 Aviation Avenue &

600 Aviation Avenue & 100 Agnew Drive Brandon Manitoba ~ 5 Acres Land For Sale SUBJECT PROPERTIES Dan Fontaine Business Development Specialist 204.729.2133 or 1.866.729.2132 [email protected] EconomicDevelopmentBrandon.com 600 Aviation Ave & 100 Agnew Drive Page 1 of 5 Property Overview PROPERTY SUMMARY Roll Numbers: 540492 & 540476 Addresses: 600 Aviation Avenue & 100 Agnew Avenue Legal Description: Lots 1&2, Block 1, Plan 38795 Zoning: Industrial General (MG) Zoning By-law 7124.pdf Lot size: 600 Aviation Ave: 1.5 Acres approx. 100 Agnew Drive: 3.5 Acres approx. Assessed value: 600 Aviation Ave: $39,300 (land only) 100 Agnew Drive: $90,900 (Land only) Property Taxes: 600 Aviation Ave: $1,039 (2018 Net) 100 Agnew Drive: $2,403 (2018 Net) Property Search Asking Price: Negotiable HIGHLIGHTS • Located on the City of Brandon Municipal Airport (McGill Field). • Easy access to the Trans-Canada Hwy, via Highway #10/1st Street. • All utilities are available in the area. • Two parcels of land same ownership can be purchased individually or as one parcel. • The Airport provides daily West Jet air service to Calgary AB. • The Airport is home to: o New Terminal Building (arrival & departure lounges and extensive parking). o Nav Canada Flight Service Station. o Enterprise Rent-A-Car Services. o The Brandon Flight Centre. o The Manitoba Emergency Services College Training facility. o Maple leaf aviation, Clarks Poultry, The Commonwealth Air Training Plan Museum. 600 Aviation Ave & 100 Agnew Drive Page 2 of 5 Economic Overview of Brandon Manitoba At the very heart of North America lies Brandon Manitoba, a city that has built its reputation on providing an environment in which business can succeed. -

Annual Report 2017-EN.Pdf

We Are NAV CANADA ANNUAL REPORT 2017 We Are NAV CANADA ANNU A L REPO R T 2017 "I perform corrective and preventive maintenance or field modifications on electronic navigational aids used by NAV CANADA, helping to ensure the safety of the air navigation system." Marc Alivio Electronics Technologist St. John’s Control Tower For definitions of the abbreviations and acronyms that appear in this report, please refer to our glossary on page 48. Corporate Profile NAV CANADA is a private, not-for-profit company, established in 1996, providing air traffic control, airport advisory and aeronautical information services, and weather briefings for more than 18 million square kilometres of Canadian domestic and international airspace. The Company is internationally recognized for its safety record, and innovative technology used by ANSPs worldwide. OUR VISION, MISSION AND OBJECTIVES Our Vision Our Overarching NAV CANADA’s Vision is to be the world’s most Objectives respected ANSP: The Company will achieve its Mission by: • in the eyes of the public for our safety record; 1 Maintaining a safety record in the top decile • in the eyes of our customers for our fee levels, of major ANSPs worldwide; customer service, efficiency and modern technology; and 2 Maintaining ANS customer service charges, on average, in the bottom quartile (lowest charges) • in the eyes of our employees for establishing of major ANSPs worldwide by ensuring that the a motivating and satisfying workplace with growth in costs of providing air navigation services competitive compensation -

NAV CANADA and Airspace Change

NAV CANADA and Airspace Change Jonathan Bagg Senior Manager, Stakeholder and Industry Relations Blake Cushnie National Manager, Performance Based Operations Overview • NAV CANADA and Airspace Change • Non-acoustic factors that impact our work • Noise mitigation through PBN About NAV CANADA • Canada’s Air Navigation Services Provider • Private, not-for-profit organization • One of the largest in the world in terms of aircraft movements • ~5,000 employees at more 100 corporate and operational sites Airspace Change Context • Well in to a significant airspace modernization program. • Driven by our State Mandate, informed by ICAO Aviation System Block Upgrades (ASBU). • NavAid modernization program – shift from ground-based to satellite-based infrastructure. • 16 airports in the last three years, where we have deployed PBN improvements including RNP-AR Airspace Change Process Airspace Change Communication and Consultation Protocol – Established in 2015 – How and when consultation should occur • Altitude of change • Changes in frequency • Impact driven • Outreach mechanisms • Noise Modelling • Reporting Requirements – Promotes industry participation and highlights ANS-Airport Authority relationship Airspace Change Process Integration of our teams and stakeholders • Deployment Team and Stakeholder Relations work closely together from the beginning. • Airport and airline involvement participation. • Community Consultation on airspace proposals. PBN Opportunities • Increase use of quieter continuous descent operations. • Better avoidance of residentially populated areas in some cases. Non Acoustical Challenges • Range of individual concern can vary in relation to expected/actual level of exposure. • An information/understanding vacuum can be easily be filled with apprehension or misinformation. • It can take time for real improvements to the noise environment to result in improved community perception. -

Arctic Surveillance Civilian Commercial Aerial Surveillance Options for the Arctic

Arctic Surveillance Civilian Commercial Aerial Surveillance Options for the Arctic Dan Brookes DRDC Ottawa Derek F. Scott VP Airborne Maritime Surveillance Division Provincial Aerospace Ltd (PAL) Pip Rudkin UAV Operations Manager PAL Airborne Maritime Surveillance Division Provincial Aerospace Ltd Defence R&D Canada – Ottawa Technical Report DRDC Ottawa TR 2013-142 November 2013 Arctic Surveillance Civilian Commercial Aerial Surveillance Options for the Arctic Dan Brookes DRDC Ottawa Derek F. Scott VP Airborne Maritime Surveillance Division Provincial Aerospace Ltd (PAL) Pip Rudkin UAV Operations Manager PAL Airborne Maritime Surveillance Division Provincial Aerospace Ltd Defence R&D Canada – Ottawa Technical Report DRDC Ottawa TR 2013-142 November 2013 Principal Author Original signed by Dan Brookes Dan Brookes Defence Scienist Approved by Original signed by Caroline Wilcox Caroline Wilcox Head, Space and ISR Applications Section Approved for release by Original signed by Chris McMillan Chris McMillan Chair, Document Review Panel This work was originally sponsored by ARP project 11HI01-Options for Northern Surveillance, and completed under the Northern Watch TDP project 15EJ01 © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as represented by the Minister of National Defence, 2013 © Sa Majesté la Reine (en droit du Canada), telle que représentée par le ministre de la Défense nationale, 2013 Preface This report grew out of a study that was originally commissioned by DRDC with Provincial Aerospace Ltd (PAL) in early 2007. With the assistance of PAL’s experience and expertise, the aim was to explore the feasibility, logistics and costs of providing surveillance and reconnaissance (SR) capabilities in the Arctic using private commercial sources. -

Annual Reportopen a New Window

2019 › BEYOND THE SKIES NAV CANADA FIRST TO LAUNCH SPACE-BASED DOMESTIC AIRCRAFT SURVEILLANCE SAFER MORE EFFICIENT LOWER EMISSION AIR TRAVEL No matter how you look at it, space-based ADS-B (SB ADS-B) air traffic surveillance is a true game-changer. As an investor in Aireon, the joint venture deploying SB ADS-B, NAV CANADA continues to play a leading role in bringing this remarkable innovation to the world. For decades, air traffic surveillance and monitoring has relied mostly on ground-based radar—a system that has some shortcomings. Because it needs a line-of-sight to its target, ground-based radar can’t always track aircraft in hilly or mountainous terrain, and it can’t be deployed at all in the oceans. These kinds of limitations mean that the systems we have relied on to monitor global air traffic actually covered just 30 percent of global airspace. Looking down from a network of 66 satellites in orbit around Earth, Aireon SB ADS-B has no such limitations. It provides complete coverage—100 percent of global airspace—and it does it in real time, relaying the position, speed, heading and other data from transponder-equipped aircraft twice every second. The implementation of SB ADS-B offers tremendous benefits, especially where safety is concerned. With total coverage in real time, air traffic systems will be able to identify and address potential loss of separation between aircraft before it occurs. Should an aircraft go missing, its precise location will be known in a matter of seconds—at a time when seconds matter. -

The RIAT: a Look at the World's Largest Air Show

the Vol. 40 No. 30 AuroraAUGUST 19, 2019 NO CHARGE www.auroranewspaper.com Regional soccer takes to Greenwood fields 14 Wing Greenwood hosts the Canadian Armed Forces Atlantic regional soccer tournament Au- gust 19 to 23. RIAT: August 19 will see teams arriving for the 4 p.m. coaches’ meeting at the 14 Wing Fitness A look and Sports Centre, followed by a 5:30 p.m. meet and greet. Action gets underway August at the 20, immediately following the 8 a.m. opening ceremony on the Church Street Apple Bowl fi eld. world’s The round robin games are 70 minutes long; the play-off games are 90 minutes long. largest In the women’s division, Gage- town takes on Halifax in the fi rst game, at 8:30 a.m. August 20. At air show 2 p.m., the 14 Wing Greenwood Some of the members of 405 (Long Range Patrol) Squadron’s CP140 Aurora crew waited out some women take on Halifax. August rain on day one at the Royal International Air Tattoo, including, left Captain Fortin, front centre 21, 14 Wing meets Gagetown at Major Paquette, back Master Corporal Hovey, and right Major MacSween. Submitted 10 a.m. The women’s semi-fi nal Captain Nick Fortin, photographers, who spent their entire day will be at 10 a.m. August 22, with 405 (Long Range Patrol) Squadron snapping away at the jet aircraft, aerobatic the fi nal at 8:15 a.m. August 23. teams, propeller aircraft and any other visiting In the men’s division, the fi rst The Royal International Air Tattoo (RIAT) aircraft fortunate enough to garner an aerial game will be Halifax versus 14 began with a short flight from Newquay, photoshoot. -

Tc Aim Rac 1.1.2.2

TP 14371E Transport Canada Aeronautical Information Manual (TC AIM) RAC—RULES OF THE AIR AND AIR TRAFFIC SERVICES MARCH 26, 2020 TC AIM March 26, 2020 TRANSPORT CANADA AERONAUTICAL INFORMATION MANUAL (TC AIM) EXPLANATION OF CHANGES EFFECTIVE—MARCH 26, 2020 NOTES: 1. Editorial and format changes were made throughout the TC AIM where necessary and those that were deemed insignificant in nature were not included in the “Explanation of Changes”. 2. Effective March 31, 2016, licence differences with ICAO Annex 1 standards and recommended practices, previously located in LRA 1.8 of the TC AIM, have been removed and can now be found in AIP Canada (ICAO) GEN 1.7. RAC (1) RAC 1.1.2.1 Flight Information Centres (FICs) In (b) FISE, fireball reporting procedures were removed. The reporting of fireball occurrences is no longer required by the government or military. (2) RAC 1.1.2.2 Flight Service Stations (FSSs) (a) AAS As NAV CANADA moves ahead with runway determination at FSSs with direct wind reading instruments, the phraseology will be changing from “preferred runway” to “runway”. (3) RAC 9.2.1 Minimum Sector Altitude (MSA) A note was added regarding the flight validation of MSA. (4) RAC 9.6.2 Visual Approach Additional text was added to clarify information about ATC visual approach clearance and missed approach procedures for aircraft on an IFR flight plan. (5) RAC 9.17.1 Corrections for Temperature Information was added to clarify some temperature correction procedures. (6) RAC 9.17.2 Remote Altimeter Setting The information was updated to specify the instrument approach procedure segments to which the RASS adjustments are applied. -

Canadian ATC Exam Study Guide

AIR TRAFFIC CONTROL STUDY GUIDE Foreword This study guide contains information considered necessary for the successful completion of the examination conducted in association with the selection process for Air Cadet candidates of the Air Traffic Control course. This information is not intended for any other purpose. The information in this guide is taken from several publications and was accurate at time of printing. This study guide will not be amended. Excerpts from, "From The Ground Up, 28th Millennium Edition", have been reprinted with the permission of the publisher, Aviation Publishers Co. Limited, and each direct quote will be indicated thus; " . "FTGU and page number. Date of Printing 01 April 2001 TABLE OF CONTENTS DEFINITIONS ABBREVIATIONS Chapter 1 COMMUNICATION PROCEDURES Chapter 2 AIRPORTS Chapter 3 NAVIGATION Chapter 4 NAVIGATION AIDS Chapter 5 CANADIAN AIRSPACE AND AIR TRAFFIC CONTROL Chapter 6 AERODYNAMICS Chapter 7 AIRCRAFT OPERATING SPECIFICATIONS Chapter 8 METEOROLOGY Chapter 9 AERONAUTICAL CHARTS DEFINITIONS As used in this study guide, the following terms have the meanings defined. NOTE: Some definitions have been abridged. AIR TRAFFIC CONTROL The objective of Air Traffic Control is to maintain a safe, orderly and expeditious flow of air traffic under the control of an appropriate unit. AIR TRAFFIC CONTROL CLEARANCE Authorization issued by an ATC unit for an aircraft to proceed within controlled Airspace in accordance with the conditions specified by that unit. AIR TRAFFIC SERVICES The following services are provided by ATC units: a. IFR CONTROL SERVICES 1. Area Control Service Provided by ACC's to IFR and CVFR aircraft. 2. Terminal Control Service Provided by ACC's and TCU's (incl. -

Student Background Pack Cross Curricula Learning Covering English, PSHE and Citizenship, Drama, Geography, History

Student Background Pack Cross curricula learning covering English, PSHE and Citizenship, Drama, Geography, History. Created in collaboration with The ArtsLink, TDF Education Department, La Jolla Playhouse and Seattle Repertory Theatre Contents From David and Irene, the writers 3 Come From Away – background and story 4 Getting to Know Newfoundland 5 History and culture 6 Geographical location 7 How do people make money in Gander? 8 Some steps to becoming a Newfoundlander 9 OPERATION YELLOW RIBBON 11 2011 – 10 Year Reunion 12 Post-show notes 14 Going further 17 (Original Broadway cast photography by Matthew Murphy, 2017) 2 FROM DAVID AND IRENE Hello, Welcome to the Rock! When we traveled to Newfoundland in September 2011 on the tenth anniversary of 9/11, we had no idea that our journey would bring us to London. We spent a month in Gander, Newfoundland and the surrounding communities meeting with the locals, returning flight crews and pilots, and returning “come from aways” (a Newfoundland term for a visitor from beyond the island) who gathered to celebrate the hope that emerged from tragedy. We didn’t know what we were looking for, but thankfully the people of Newfoundland are incredible storytellers. As we heard numerous tales of ordinary people and extraordinary generosity, it became clear that during the week of 9/11, for the 7,000 stranded passengers and people of Newfoundland, the island was a safe harbor in a world thrown into chaos. We laughed, we cried, we were invited over for dinner and offered cars. We made lifetime friends out of strangers and we came home wanting to share every story we heard – about 16,000 of them! Through this journey, we’ve learned it’s important to tell stories about welcoming strangers and stories of kindness. -

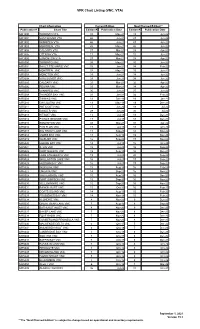

VFR Chart Listing (VNC, VTA)

VFR Chart Listing (VNC, VTA) Chart Information Current Edition Next Planned Edition** Publication # Chart Title Edition # Publication Date Edition # Publication Date AIR1900 TORONTO VTA 48 May-21 49 Jun-22 AIR1901 VANCOUVER VTA 46 Jun-21 47 Jun-22 AIR1902 WINNIPEG VTA 46 Jun-21 47 Jun-22 AIR1903 MONTREAL VTA 45 May-21 46 Jun-22 AIR1904 CALGARY VTA 27 Mar-21 28 Apr-22 AIR1905 OTTAWA VTA 11 May-21 12 Jun-22 AIR1906 EDMONTON VTA 27 Mar-21 28 Apr-22 AIR5000 TORONTO VNC 39 May-21 40 Jun-22 AIR5001 SAULT STE MARIE VNC 33 Jan-21 34 Feb-22 AIR5002 MONTREAL VNC 32 May-21 33 Jun-22 AIR5003 MONCTON VNC 33 Jun-21 34 Jun-22 AIR5004 VANCOUVER VNC 33 Jun-21 34 Jun-22 AIR5005 CALGARY VNC 31 Mar-21 32 Apr-22 AIR5006 REGINA VNC 33 Mar-21 34 Apr-22 AIR5007 WINNIPEG VNC 36 Jun-21 37 Jun-22 AIR5008 THUNDER BAY VNC 33 Jan-21 34 Feb-22 AIR5009 TIMMINS VNC 18 Dec-19 19 Jan-22 AIR5010 CHICOUTIMI VNC 18 May-19 19 Dec-21 AIR5011 ANTICOSTI VNC 17 Jun-20 18 Jul-22 AIR5012 GANDER VNC 29 Jun-20 30 Jul-22 AIR5013 KITIMAT VNC 17 Jul-19 18 Dec-21 AIR5014 PRINCE GEORGE VNC 17 Jul-19 18 Dec-21 AIR5015 EDMONTON VNC 33 Mar-21 34 Apr-22 AIR5016 FLIN FLON VNC 17 Jul-19 18 Oct-23 AIR5017 BIG TROUT LAKE VNC 17 Sep-20 18 Nov-22 AIR5018 JAMES BAY VNC 18 Aug-19 19 Nov-23 AIR5019 WABUSH VNC 16 Sep-20 17 Nov-22 AIR5020 GOOSE BAY VNC 14 Jul-19 15 Oct-23 AIR5021 ATLIN VNC 15 Jul-20 16 Sep-22 AIR5022 FORT NELSON VNC 15 Aug-19 16 Dec-21 AIR5023 LAKE ATHABASCA VNC 19 Jul-20 20 Sep-22 AIR5024 WOLLASTON LAKE VNC 16 Jul-20 17 Sep-22 AIR5025 HUDSON BAY VNC 16 Jul-20 17 Sep-22 AIR5026 INUKJUAK