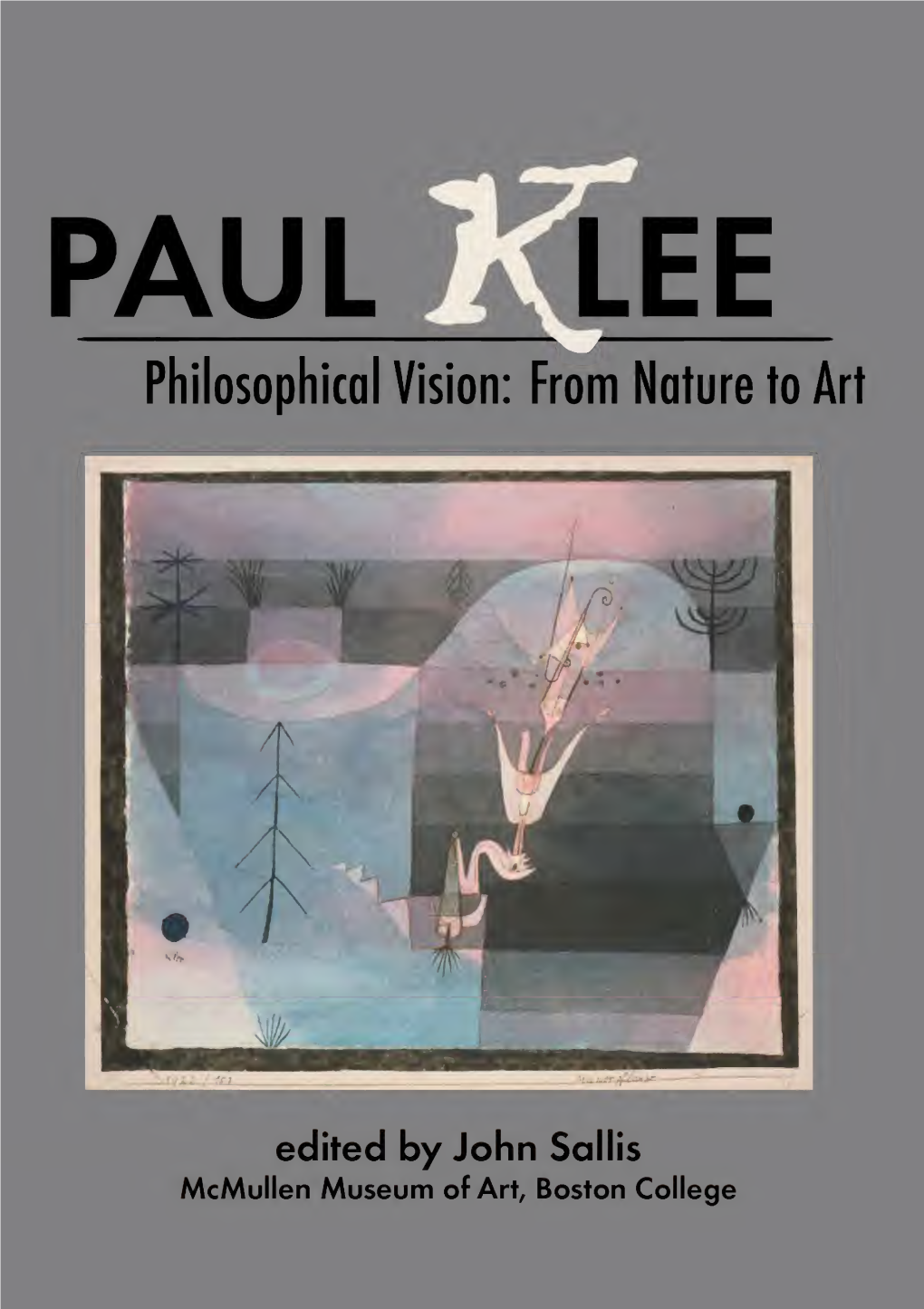

Paul Klee : Philosophical Vision, from Nature To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planning Curriculum in Art and Design

Planning Curriculum in Art and Design Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction Planning Curriculum in Art and Design Melvin F. Pontious (retired) Fine Arts Consultant Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction Tony Evers, PhD, State Superintendent Madison, Wisconsin This publication is available from: Content and Learning Team Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction 125 South Webster Street Madison, WI 53703 608/261-7494 cal.dpi.wi.gov/files/cal/pdf/art.design.guide.pdf © December 2013 Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction The Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction does not discriminate on the basis of sex, race, color, religion, creed, age, national origin, ancestry, pregnancy, marital status or parental status, sexual orientation, or disability. Foreword Art and design education are part of a comprehensive Pre-K-12 education for all students. The Wisconsin Department of Public Instruction continues its efforts to support the skill and knowledge development for our students across the state in all content areas. This guide is meant to support this work as well as foster additional reflection on the instructional framework that will most effectively support students’ learning in art and design through creative practices. This document represents a new direction for art education, identifying a more in-depth review of art and design education. The most substantial change involves the definition of art and design education as the study of visual thinking – including design, visual communications, visual culture, and fine/studio art. The guide provides local, statewide, and national examples in each of these areas to the reader. The overall framework offered suggests practice beyond traditional modes and instead promotes a more constructivist approach to learning. -

The American Abstract Artists and Their Appropriation of Prehistoric Rock Pictures in 1937

“First Surrealists Were Cavemen”: The American Abstract Artists and Their Appropriation of Prehistoric Rock Pictures in 1937 Elke Seibert How electrifying it must be to discover a world of new, hitherto unseen pictures! Schol- ars and artists have described their awe at encountering the extraordinary paintings of Altamira and Lascaux in rich prose, instilling in us the desire to hunt for other such discoveries.1 But how does art affect art and how does one work of art influence another? In the following, I will argue for a causal relationship between the 1937 exhibition Prehis- toric Rock Pictures in Europe and Africa shown at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and the new artistic directions evident in the work of certain New York artists immediately thereafter.2 The title for one review of this exhibition, “First Surrealists Were Cavemen,” expressed the unsettling, alien, mysterious, and provocative quality of these prehistoric paintings waiting to be discovered by American audiences (fig. ).1 3 The title moreover illustrates the extent to which American art criticism continued to misunderstand sur- realist artists and used the term surrealism in a pejorative manner. This essay traces how the group known as the American Abstract Artists (AAA) appropriated prehistoric paintings in the late 1930s. The term employed in the discourse on archaic artists and artistic concepts prior to 1937 was primitivism, a term due not least to John Graham’s System and Dialectics of Art as well as his influential essay “Primitive Art and Picasso,” both published in 1937.4 Within this discourse the art of the Ice Age was conspicuous not only on account of the previously unimagined timespan it traversed but also because of the magical discovery of incipient human creativity. -

Understanding the Value of Arts & Culture | the AHRC Cultural Value

Understanding the value of arts & culture The AHRC Cultural Value Project Geoffrey Crossick & Patrycja Kaszynska 2 Understanding the value of arts & culture The AHRC Cultural Value Project Geoffrey Crossick & Patrycja Kaszynska THE AHRC CULTURAL VALUE PROJECT CONTENTS Foreword 3 4. The engaged citizen: civic agency 58 & civic engagement Executive summary 6 Preconditions for political engagement 59 Civic space and civic engagement: three case studies 61 Part 1 Introduction Creative challenge: cultural industries, digging 63 and climate change 1. Rethinking the terms of the cultural 12 Culture, conflict and post-conflict: 66 value debate a double-edged sword? The Cultural Value Project 12 Culture and art: a brief intellectual history 14 5. Communities, Regeneration and Space 71 Cultural policy and the many lives of cultural value 16 Place, identity and public art 71 Beyond dichotomies: the view from 19 Urban regeneration 74 Cultural Value Project awards Creative places, creative quarters 77 Prioritising experience and methodological diversity 21 Community arts 81 Coda: arts, culture and rural communities 83 2. Cross-cutting themes 25 Modes of cultural engagement 25 6. Economy: impact, innovation and ecology 86 Arts and culture in an unequal society 29 The economic benefits of what? 87 Digital transformations 34 Ways of counting 89 Wellbeing and capabilities 37 Agglomeration and attractiveness 91 The innovation economy 92 Part 2 Components of Cultural Value Ecologies of culture 95 3. The reflective individual 42 7. Health, ageing and wellbeing 100 Cultural engagement and the self 43 Therapeutic, clinical and environmental 101 Case study: arts, culture and the criminal 47 interventions justice system Community-based arts and health 104 Cultural engagement and the other 49 Longer-term health benefits and subjective 106 Case study: professional and informal carers 51 wellbeing Culture and international influence 54 Ageing and dementia 108 Two cultures? 110 8. -

Outsider to Insider: the Art of the Socially Excluded

Derleme Makale YAZ 2020/SAYI 24 Review Article SUMMER 2020/ISSUE 24 Kartal, B. (2020). Outsider to insider: The art of the socially excluded. yedi: Journal of Art, Design & Science, 24, 141-149. doi: 10.17484/yedi.649932 Outsider to Insider: The Art of the Socially Excluded Dışarıdan İçeriye: Sosyal Dışlanmışların Sanatı Burcu Kartal, Department of Cartoon and Animation, İstanbul Aydın University Abstract Özet The term outsider art was coined by the art historian Roger Cardinal Toplum dışı sanat olarak da tanımlanan Outsider Art terimi ilk kez in 1972. Outsider art includes the art of the ‘unquiet minds,’ self- 1972 yılında Roger Cardinal tarafından kullanılmıştır. Toplum dışı taught and non-academic work. Outsider art is not a movement like sanat, akademik eğitim almamış, kendisini bu alanda geliştirmiş, Cubism or Expressionism with guidelines and traditions, rather it is a toplumun ‘normal’ olarak sınıflandırdığı grubun dışında kalan reflection of the social and mental status of the artist. The bireylerin yaptığı sanattır. Toplum dışı sanatın, kübizm veya classification relies more on the artist than the art. Due to such dışavurumculuk gibi belirli kuralları, çizgisi yoktur; sanatçının akli ve characteristics of the term, like wide range of freedom and urge to sosyal statüsü üzerinden sınıflandırılır. Bu nedenle toplum dışı sanat create, social discrimination, creating without the intention of profit, sınıflandırması sanat değil sanatçı üzerindendir. Toplum dışı sanatın people with Autism Spectrum Disorder also considered as Outsiders. ana özellikleri içerisinde önüne geçilemez yaratma isteği, sosyal However, not all people with Autism Spectrum Disorder has the dışlanma, kazanç sağlama hedefi olmadan üretme olduğu skillset to be an artist. -

Dialogues in Philosophy, Mental and Neuro Sciences Crossing Dialogues ORIGINAL ARTICLE

Dialogues in Philosophy, Mental and Neuro Sciences Crossing Dialogues ORIGINAL ARTICLE Association Madman and Philosopher: Ideas of Embodiment between Aby Warburg and Ernst Cassirer AEP Meeting of Psychopathologists at Hospital Corentin Celton, Paris (France), December 2016 N A Introduction 15.11.1921: Severe delusional ideas during lunchtime: cabage is the brain of his brother, potatoes are the heads of his children, meat is the human fl esh of his relatives, milk is not from the cow, eating a sandwich is eating his own son […] 19.11.1921: Three children have been slaughtered and have been eaten by patients. Three dead kids are lying in the nurse’s bed […] 09.04.1922: Patient very aggressive, boxing, hitting out and injuring nurse and doctor. Feels his nurse, coming back from leave has killed all his relatives on the order of Dr. Binswanger. Keywords: embodiement, psychopathology, Binswanger, Cassirer, Warburg. DIAL PHIL MENT NEURO SCI 2017; 10(1): 14-22 These are only a few of numerous reports form though, remains focussed on the abstract from the hospital-fi les of Aby Warburg during and conscious end of the symbolising process, his treatment in Kreuzlingen between 1921 thus gaining distance from concrete emotions and 1924. Despite his diagnosis of an ongoing and from being caught in physical interaction. schizohrenia (later changed to mixed manic- My presentation focusses on the original depressive state) philosopher Ernst Cassirer and encounter between Warburg and Cassirer, on historian of culture Fritz Saxl tried to convince the contemporary controversies about Warburg’s cilinic director Ludwig Binswanger to give madness, and on the wider implications the permission to Warburg to restart his cultural whole Kreuzlingen szenario might have with studies about the Hopi Snake-Ritual as it might regards to the implementation of symbolic/ stabilise his mental balance. -

Redalyc.La Colección Prinzhorn: Una Relación Falaz Entre El Arte Y La Locura

Arte, Individuo y Sociedad ISSN: 1131-5598 [email protected] Universidad Complutense de Madrid España SÁNCHEZ MORENO, IVÁN; RAMOS RÍOS, NORMA La colección Prinzhorn: Una relación falaz entre el arte y la locura Arte, Individuo y Sociedad, vol. 18, 2006, pp. 131-150 Universidad Complutense de Madrid Madrid, España Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=513551274005 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto 07. Sanchez Ivan.qxp 31/05/2006 10:22 Página 131 La colección Prinzhorn: Una relación falaz entre el arte y la locura Prinzhorn: a fallacious relation between art and madness IVÁN SÁNCHEZ MORENO Y NORMA RAMOS RÍOS Pontificia Universidad Católica de Valparaíso [email protected], [email protected] Recibido: 5 demayo de 2005 Aprobado: 4 de julio de 2005 RESUMEN: El presente artículo pretende mostrar cómo la psiquiatría, a lo largo de la historia, ha mantenido una relación falaz con el mundo del arte. Los autores se sirven de la colección de arte realizado por enfermos mentales que estudió el doctor Hans Prinzhorn a principios del siglo XX. La tradición histórica interesada en la relación entre la creatividad, el arte y la locura se remonta a la antigüedad llegando hasta la aparición de la psicología y la psiquiatría como ciencias autónomas. Destacados autores ahondaron en el campo de la psicología del arte e influyeron al doctor Prinzhorn quien, a su vez, se convertiría años después en un referente para los artistas de vanguardia. -

Modernist Ekphrasis and Museum Politics

1 BEYOND THE FRAME: MODERNIST EKPHRASIS AND MUSEUM POLITICS A dissertation presented By Frank Robert Capogna to The Department of English In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the field of English Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts April 2017 2 BEYOND THE FRAME: MODERNIST EKPHRASIS AND MUSEUM POLITICS A dissertation presented By Frank Robert Capogna ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the College of Social Sciences and Humanities of Northeastern University April 2017 3 ABSTRACT This dissertation argues that the public art museum and its practices of collecting, organizing, and defining cultures at once enabled and constrained the poetic forms and subjects available to American and British poets of a transatlantic long modernist period. I trace these lines of influence particularly as they shape modernist engagements with ekphrasis, the historical genre of poetry that describes, contemplates, or interrogates a visual art object. Drawing on a range of materials and theoretical formations—from archival documents that attest to modernist poets’ lived experiences in museums and galleries to Pierre Bourdieu’s sociology of art and critical scholarship in the field of Museum Studies—I situate modernist ekphrastic poetry in relation to developments in twentieth-century museology and to the revolutionary literary and visual aesthetics of early twentieth-century modernism. This juxtaposition reveals how modern poets revised the conventions of, and recalibrated the expectations for, ekphrastic poetry to evaluate the museum’s cultural capital and its then common marginalization of the art and experiences of female subjects, queer subjects, and subjects of color. -

ELEMENTARY ART Integrated Within the Regular Classroom Linda Fleetwood NEISD Visual Art Director WAYS ART TAUGHT WITHIN NEISD

ELEMENTARY ART Integrated Within the Regular Classroom Linda Fleetwood NEISD Visual Art Director WAYS ART TAUGHT WITHIN NEISD • Woven into regular elementary classes – integration • Instructional Assistants specializing in art – taught within rotation • Parents/Volunteers – usually after school • Art Clubs sponsored by elementary teachers – usually after school • Certified Art Teachers (2) – Castle Hills Elementary & Montgomery Elementary ELEMENTARY LESSON DESIGNS • NEISD Visual Art Webpage (must be logged in) https://www.neisd.net/Page/687 to find it open NEISD website > Departments > Fine Arts > Visual Art on left • Curriculum Available K-5 • Elementary Art TEKS • Lesson Designs (listed by topic and grade level) SOURCES FOR LESSON DESIGNS • Pinterest https://www.pinterest.com/ • YouTube • Art to Remember https://arttoremember.com/lesson-plans/ • SAX/School Specialty (an art supply source) https://www.schoolspecialty.com/ideas- resources/lesson-plans#pageView:list • Blick Lesson Plans (an art supply source) https://www.dickblick.com/lesson-plans/ LESSON TODAY, GRADES K-1 • Gr K-1, “Kitty Cat with Her Bird” • Integrate with Math Shapes • Based on Paul Klee • Discussion: Book The Cat and the Bird by Geraldine Elschner & Peggy Nile and watch the “How To” video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tW6MmY4xPe8 • Artwork: Cat and Bird, 1928 LESSON TODAY, GRADES 2-3 • Gr 2-3, “Me, On Top of Colors” • Integrate with Social Studies with Personal Identity, Math Shapes • Based on Paul Klee • Discussion: Poem Be Glad Your Nose Is On Your Face by Jack -

Art, Life Story and Cultural Memory: Profiles of the Artists of the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial Elise S

University of St. Thomas, Minnesota UST Research Online Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership School of Education Spring 2015 Art, Life Story and Cultural Memory: Profiles of the Artists of the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial Elise S. Roberts University of St. Thomas, Minnesota, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.stthomas.edu/caps_ed_lead_docdiss Part of the Art Education Commons, Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons, Educational Leadership Commons, Educational Methods Commons, Liberal Studies Commons, Other Education Commons, Other Educational Administration and Supervision Commons, and the Urban Education Commons Recommended Citation Roberts, Elise S., "Art, Life Story and Cultural Memory: Profiles of the Artists of the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial" (2015). Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership. 63. https://ir.stthomas.edu/caps_ed_lead_docdiss/63 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Education at UST Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership by an authorized administrator of UST Research Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Art, Life Story and Cultural Memory: Profiles of the Artists of the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE SCHOOL OF EDUCATION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ST. THOMAS ST. PAUL, MINNESOTA By Elise S. Roberts IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF EDUCATION May 2015 UNIVERSITY OF ST. THOMAS MINNESOTA Art, Life Story and Cultural Memory: Profiles of the Artists of the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial We certify that we have read this dissertation and approved it as adequate in scope and quality. -

Else Alfelt, Lotti Van Der Gaag, and Defining Cobra

WAS THE MATTER SETTLED? ELSE ALFELT, LOTTI VAN DER GAAG, AND DEFINING COBRA Kari Boroff A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2020 Committee: Katerina Ruedi Ray, Advisor Mille Guldbeck Andrew Hershberger © 2020 Kari Boroff All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katerina Ruedi Ray, Advisor The CoBrA art movement (1948-1951) stands prominently among the few European avant-garde groups formed in the aftermath of World War II. Emphasizing international collaboration, rejecting the past, and embracing spontaneity and intuition, CoBrA artists created artworks expressing fundamental human creativity. Although the group was dominated by men, a small number of women were associated with CoBrA, two of whom continue to be the subject of debate within CoBrA scholarship to this day: the Danish painter Else Alfelt (1910-1974) and the Dutch sculptor Lotti van der Gaag (1923-1999), known as “Lotti.” In contributing to this debate, I address the work and CoBrA membership status of Alfelt and Lotti by comparing their artworks to CoBrA’s two main manifestoes, texts that together provide the clearest definition of the group’s overall ideas and theories. Alfelt, while recognized as a full CoBrA member, created structured, geometric paintings, influenced by German Expressionism and traditional Japanese art; I thus argue that her work does not fit the group’s formal aesthetic or philosophy. Conversely Lotti, who was never asked to join CoBrA, and was rejected from exhibiting with the group, produced sculptures with rough, intuitive, and childlike forms that clearly do fit CoBrA’s ideas as presented in its two manifestoes. -

Outsider Art in Contemporary Museums: the Celebration of Politics Or Artistry?

L A R A O T A N U K E | T 2 0 1 S 8 I D E R A LET M E SAY THI S ABOUT THAT R T ANARTI STICCEL LETS EBRATIO NORAPO LITICALT RIUMPH TALK OUTSIDER ART IN CONTEMPORARY MUSEUMS: THE CELEBRATION OF POLITICS OR ARTISTRY? Student Name: Lara Tanke Student Number: 455457 Supervisor: B. Boross Master Art, Culture & Society Erasmus School of History, Culture and Communication Erasmus University Rotterdam ACS Master Thesis June, 2018 2 ABSTRACT Outsider Art is booming in the legitimate, contemporary art world (Tansella, 2007; Chapin, 2009). Contrary to Insider Art -objects that are created by trained artists on the basis of accepted, pre-existing concepts, frameworks or representations-, Outsider Art is made by untrained artists who create for no-one but themselves by reacting to internal, not external, prerequisites. It is their individual quirkiness and idiosyncrasy that stands out and for that reason, Outsider Art is celebrated because of the authentic autobiography of the maker. As Outsider Art is not based on a goldmine of traditions” (Tansella, 2007, p. 134) such as a predetermined vision and a stylistic framework -as it is the case with Insider Art-, gatekeepers want to make sure that audiences are aware of the difference between the oppositional categories: they deconstruct the aesthetic system by justifying the objects on the basis of the artist’s biography. The art evaluation of audience is affected by the authority that cultural institutions and the cultural elite enjoy when it comes to their legitimizing power to turn objects in to art (Becker, 1982; Bourdieu, 1984). -

The State of Art Criticism

Page 1 The State of Art Criticism Art criticism is spurned by universities, but widely produced and read. It is seldom theorized, and its history has hardly been investigated. The State of Art Criticism presents an international conversation among art historians and critics that considers the relation between criticism and art history, and poses the question of whether criticism may become a university subject. Participants include Dave Hickey, James Panero, Stephen Melville, Lynne Cook, Michael Newman, Whitney Davis, Irit Rogoff, Guy Brett, and Boris Groys. James Elkins is E.C. Chadbourne Chair in the Department of Art History, Theory, and Criticism at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. His many books include Pictures and Tears, How to Use Your Eyes, and What Painting Is, all published by Routledge. Michael Newman teaches in the Department of Art History, Theory, and Criticism at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and is Professor of Art Writing at Goldsmiths College in the University of London. His publications include the books Richard Prince: Untitled (couple) and Jeff Wall, and he is co-editor with Jon Bird of Rewriting Conceptual Art. 08:52:27:10:07 Page 1 Page 2 The Art Seminar Volume 1 Art History versus Aesthetics Volume 2 Photography Theory Volume 3 Is Art History Global? Volume 4 The State of Art Criticism Volume 5 The Renaissance Volume 6 Landscape Theory Volume 7 Re-Enchantment Sponsored by the University College Cork, Ireland; the Burren College of Art, Ballyvaughan, Ireland; and the School of the Art Institute, Chicago. 08:52:27:10:07 Page 2 Page 3 The State of Art Criticism EDITED BY JAMES ELKINS AND MICHAEL NEWMAN 08:52:27:10:07 Page 3 Page 4 First published 2008 by Routledge 270 Madison Ave, New York, NY 10016 Simultaneously published in the UK by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2007.