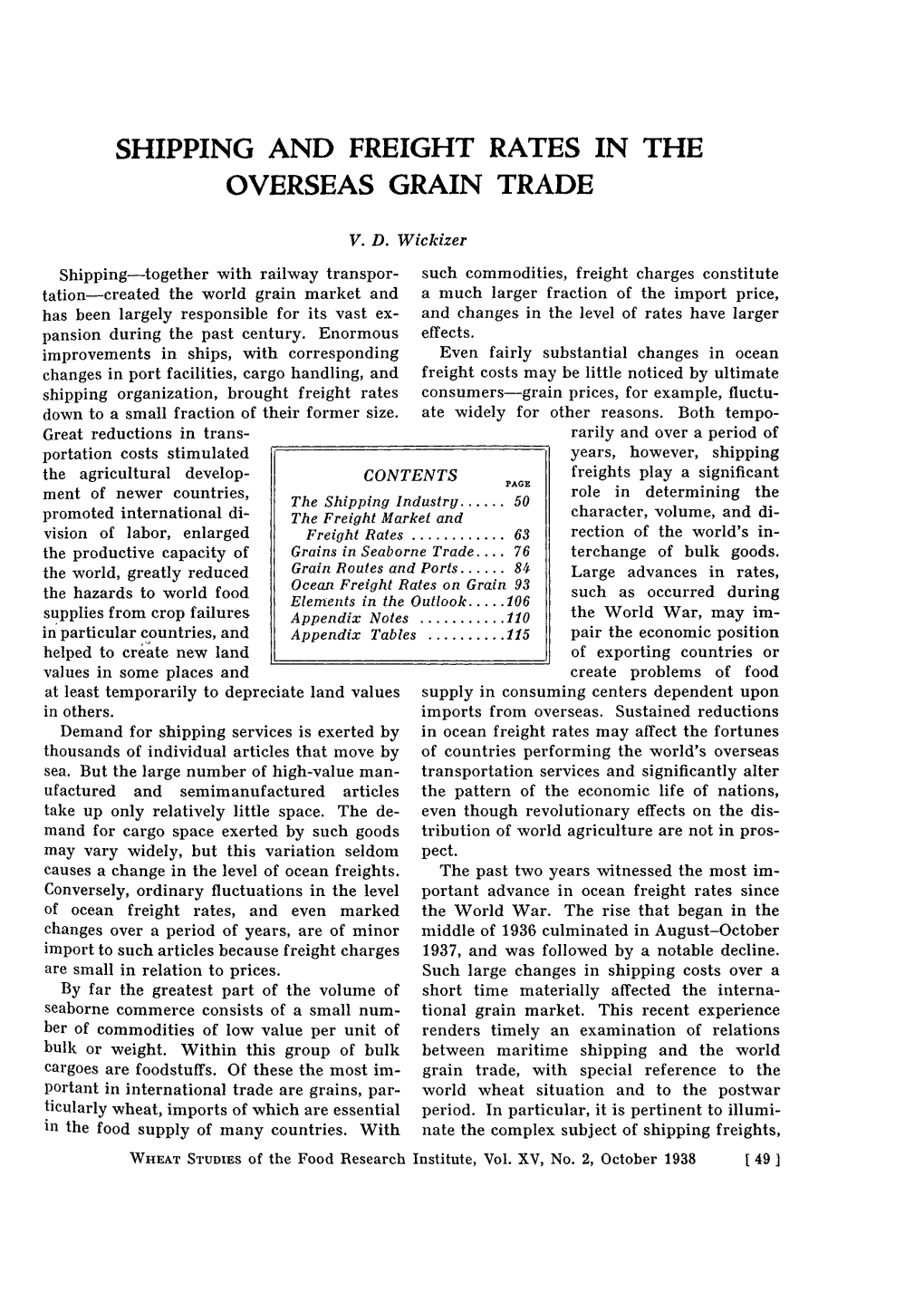

Shipping and Freight Rates in the Overseas Grain Trade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regulatory Issues in International Martime Transport

Organisation de Coopération et de Développement Economiques Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development __________________________________________________________________________________________ Or. Eng. DIRECTORATE FOR SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY AND INDUSTRY DIVISION OF TRANSPORT REGULATORY ISSUES IN INTERNATIONAL MARTIME TRANSPORT Contact: Mr. Wolfgang Hübner, Head of the Division of Transport, DSTI, Tel: (33 1) 45 24 91 32 ; Fax: (33 1) 45 24 93 86 ; Internet: [email protected] Or. Eng. Or. Document complet disponible sur OLIS dans son format d’origine Complete document available on OLIS in its original format 1 Summary This report focuses on regulations governing international liner and bulk shipping. Both modes are closely linked to international trade, deriving from it their growth. Also, as a service industry to trade international shipping, which is by far the main mode of international transport of goods, has facilitated international trade and has contributed to its expansion. Total seaborne trade volume was estimated by UNCTAD to have reached 5330 million metric tons in 2000. The report discusses the web of regulatory measures that surround these two segments of the shipping industry, and which have a considerable impact on its performance. As well as reviewing administrative regulations to judge whether they meet their intended objectives efficiently and effectively, the report examines all those aspects of economic regulations that restrict entry, exit, pricing and normal commercial practices, including different forms of business organisation. However, those regulatory elements that cover competition policy as applied to liner shipping will be dealt with in a separate study to be undertaken by the OECD Secretariat Many measures that apply to maritime transport services are not part of a regulatory framework but constitute commercial practices of market operators. -

Frequently Overlooked Risk Management Issues in Contracts of Affreightment and Sale Contracts

Frequently overlooked risk management issues in contracts of affreightment and sale contracts 2021 AMPLA Queensland Conference Chris Keane MinterEllison 18 June 2021 The focus of today’s presentation - risk associated with two contracts used to facilitate the export of Australian commodities: . the sale contract / offtake agreement / supply agreement (sale contract) . the contract of affreightment / voyage charterparty / bill of lading (sea carriage contract) Specific focus is on risk and risk mitigation options that are frequently overlooked (both at the time of contract formation and also when disputes arise) 2 Risk arising out of seemingly straightforward issues . Duration of the sale contract - overarching issue that impacts on many other considerations; legal and commercial considerations will overlap . Port(s) of loading and port(s) of discharge - relevant considerations include: access to certain berths; special arrangements regarding loading and unloading; port congestion and other factors likely to cause delay; and the desirability of not requiring a CIF buyer to nominate a specific port of unloading (e.g. “one safe port and one safe berth at any main port(s) in China…”) . Selection of vessel - risk will depend on which party to the sale contract is responsible for arranging the vessel; CIF sellers need to guard against the risk of selecting an unsuitable vessel; FOB sellers need to ensure they have a right to reject an unsuitable vessel nominated by the buyer 3 Risk arising out of seemingly straightforward issues . Selection of contractual carrier - needs to be considered as an issue separate from the selection of the vessel; what do you know (and not know) about the carrier?; note the difficulties the contractual carrier caused for both the seller and buyer in relation to the ‘Maryam’ at Port Kembla earlier this year; proper due diligence is critical; consider (among other things) compliance with anti-slavery, anti-bribery and sanctions laws and issues concerning care of seafarers, safety and environment . -

Volume Contracts of Affreightment – Some Features and Principles

Volume Contracts of Affreightment – Some Features and Principles Lars Gorton 1 Introduction ………………………………………………………………….…. 62 1.1 General Background ……………………………………………………… 62 1.2 Some Contractual Points …………..……………………………………... 62 1.3 Frame Agreements ………………………………………………………... 64 1.4 Some General Points Related to Distributorship Agreements and Volume Contracts ………………………………………. 66 1.5 Some Further Overriding Points ……………………………………….…. 67 2 Contract Forms ………………………………………………………………… 68 3 Law, Contract and Terminology ……………………………………………… 69 4 The SMC Rules on Volume Contracts ……………………………………..…. 70 5 Characteristics of COA’s ……………………………………………………… 71 6 The Generic Nature of the COA ………………………………………………. 72 7 Some of the Parameters of the COA ………………………...……………….. 76 7.1 The Ships Involved Under the Volume Contract ………………………… 76 7.2 Time Elements in Connection with COA’s ………………………………. 76 7.3 Cargo and Cargo Quantity and Planning of Voyages ………………….… 77 8 Breach and Consequences of Breach …………………………………………. 78 8.1 Generally, Best Efforts and Cooperation …………………………………. 78 8.2 Consequences of the Owners’s Breach …………………………………... 78 8.3 Consequences of the Charterer’s Breach …………………………………. 78 9 Some Comparisons with Distributorship Agreements in English Law ….…. 78 10 Some COA Cases Involving “Evenly spread” ……………………………….. 82 10.1 “Evenly spread” …………………………………………………………... 82 10.2 Mitigation of Damages …………………………………………………… 85 11 Freight, Demurrage and Similar ……………………………………………… 88 11.1 General Points ………..…………………………………………………... 88 11.2 Freight Level …………………………………………………………….. -

The Rail Freight Challenge for Emerging Economies How to Regain Modal Share

The Rail Freight Challenge for Emerging Economies How to Regain Modal Share Bernard Aritua INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT IN FOCUS INTERNATIONAL INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT IN FOCUS The Rail Freight Challenge for Emerging Economies How to Regain Modal Share Bernard Aritua © 2019 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org Some rights reserved 1 2 3 4 22 21 20 19 Books in this series are published to communicate the results of Bank research, analysis, and operational experience with the least possible delay. The extent of language editing varies from book to book. This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpre- tations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Nothing herein shall constitute or be considered to be a limitation upon or waiver of the privileges and immunities of The World Bank, all of which are specifically reserved. Rights and Permissions This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo. -

Freight Services the Alaska Railroad (ARRC) Provides Seam- ARM Barge Move from Whittier to Anchorage Or Less Freight Operation Between Shipping Points in Fairbanks

Freight Services The Alaska Railroad (ARRC) provides seam- ARM barge move from Whittier to Anchorage or less freight operation between shipping points in Fairbanks. Barges also move railcar shipments the Lower 48 to many destinations in Alaska. Port to/from Alaska via Prince Rupert, interchanging facilities in Seattle, Whittier, Seward and Anchor- with Canadian National Railway (CN). The CN age provide crucial links between marine and land barge was discontinued in early spring 2021. transportation modes. Rail yards in Seward, Whit- tier, Anchorage and Fairbanks offer centralized • Trailers/Containers on Flat Cars — TOFC/ distribution hubs for other transportation modes. COFC moves north and south between Seward, Whittier, Anchorage and Fairbanks. Freight Revenue & Expense • Coal — Coal from Usibelli Coal Mine in Healy Freight is the Alaska Railroad’s bread-and- moves to the Fairbanks area for local markets. butter, typically generating more than half of operating revenues (excluding capital grants). In • Gravel — Seasonally (April – October) aggregate 2019, a more typical year, the railroad hauled 3.49 products move from the Matanuska-Susitna million tons of freight, generating 56% of operating Valley to Anchorage. revenues. In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic dev- • Miscellaneous/In-state Local — Other freight astated ARRC’s passenger business and lowered includes specialty movements of very large or freight demand. As a result, ARRC hauled 2.8 mil- lion tons of freight, generating three-fourths (76%) oddly-shaped equipment and materials, as well of operating revenues. as in-state shipments of cement, scrap metal, Major lines of freight business include: military equipment and pipe. • Petroleum — Most petroleum products have While freight-hauling is a major revenue source, it also involves capital- and maintenance- moved from Anchorage to a fuel distribution intensive expense. -

Draft Final Report on Mtcp Tonnage Measurement Study

Tonnage Measurement Study MTCP Work Package 2.1 Quality and Efficiency Final Report Bremen /Brussels, November 2006 Disclaimer: The use of any knowledge, information or data contained in this document shall be at the user's sole risk. The members of the Maritime Transport Coordination Platform accepts no liability or responsibility, in negligence or otherwise, for any loss, damage or expense whatever sustained by any person as a result of the use, in any manner or form, of any knowledge, information or data contained in this document, or due to any inaccuracy, omission or error therein contained. The contents and the views expressed in the document remain the responsibility of the Maritime Transport Coordination Platform. The European Community shall not in any way be liable or responsible for the use of any such knowledge, information or data, or of the consequences thereof. Content 0. Executive Summary............................................................................................1 1 Introduction and Background ............................................................................2 2 Structure of Report..............................................................................................3 3. The London Tonnage Convention (1969) .......................................................4 3.1 Brief History..................................................................................................4 3.2 Purpose and Regulations of the Convention..................................................5 3.3 Definitions......................................................................................................8 -

Case 3:19-Cv-01259-JR Document 88 Filed 01/06/21 Page 1 of 16

Case 3:19-cv-01259-JR Document 88 Filed 01/06/21 Page 1 of 16 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF OREGON SHELTER FOREST INTERNATIONAL Case No. 3:19-cv-01259-JR ACQUISITION, INC., an Oregon Corporation, OPINION AND ORDER Plaintiff, v. COSCO SHIPPING (USA) INC., a Delaware Corporation; COSCO SHIPPING LINES (NORTH AMERICA) INC., a Delaware Corporation; COSCO SHIPPING TERMINALS (USA) LLC, a Delaware LLC; RUDY ROGERS, an individual; COSCO SHIPPING LINES CO., LTD.; and JANE AND JOHN DOES NOS. 1-3, Defendants. _______________________________________ RUSSO, Magistrate Judge: Shelter Forest International Acquisition, Inc. (“SFI”) filed this action against defendants COSCO Shipping (USA) Inc., COSCO Shipping Lines (North America) Inc., COSCO Shipping Terminals (USA) LLC, Rudy Rogers, and COSCO Shipping Lines Co., Ltd. (“CSL”) alleging multiple contractually-based claims under state law.1 All parties have consented to allow a Magistrate Judge enter final orders and judgment in this case in accordance with Fed. R. Civ. P. 73 and 28 U.S.C. § 636(c). CSL now moves for summary judgement on its remaining counterclaim pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 56. For the reasons stated below, CSL’s motion is granted in part and denied in part. 1 All parties except CSL were subsequently voluntarily dismissed. Page 1 – OPINION AND ORDER Case 3:19-cv-01259-JR Document 88 Filed 01/06/21 Page 2 of 16 BACKGROUND CSL is a shipping company based in China operating a fleet of oceangoing containerships that transport cargo internationally, including between China and the United States. SFI is an Oregon corporation that imports and distributes lumber, plywood, and other building materials. -

13-SHIPPING-GLOSSARY.Pdf

GLOSSARY 2H SECOND HALF A/S ALONGSIDE A&CP ANCHORS AND CHAINS PROVED A/C AIRCRAFT CARRIER A/C ACCOUNT CURRENT A/D ALTERNATIVE DAYS A/M (ANTE MERIDIEM) BEFORE NOON A/O ACCOUNT OF A/S AFTER SIGHT A/S ALONGSIDE AA ALWAYS AFLOAT AA AFTER ARRIVAL AA ALWAYS ACCESSIBLE AA AVERAGE ADJUSTER AAA AGRICULTURAL ADJUSTMENT ACT AAAA ALWAYS AFLOAT, ALWAYS ACCESSIBLE AAOSA ALWAYS AFLOAT OR SAFE AGROUND AAR AGAINST ALL RISKS AARA ALWAYS ACCESSIBLE OR REACHABLE ON ARRIVAL AB ABLE SEAMAN AB ABLE BODIED SEAMAN AB AVERAGE BOND ABS AMERICAN BUREAU OF SHIPPING ABT ABOUT AC ALTERNATIVE CURRENT AC ACCOUNT AC ALTERNATING CURRENT ACC ACCOUNT ACC ACCEPTED ACK ACKNOWLEDGE ACV AIR CUSHION VEHICLE AD AFTER DATE AD AREA DIFFERENTIAL AD VAL (AD VALOREM) ACCORDING TO VALUE ADCOM ADDRESS COMMISSION ADF AUTOMATIC DIRECTION FINDER ADJ ADJUSTMEN ADV ADVANCEMENT OF SPECIAL SURVEY ADVT ADVERTISEMENT AF ANTI-FOULING AF ADVANCED FREIGHT AF ALSO FOR AFFF AQUEOUS FILM FORMING FOAM AFRA AVERAGE FREIGHT RATE ASSESSMENT AG ARABIAN GULF AGB ICE BREAKER AGC AMPHIBIOUS VESSEL AGT AGENT AGW ACTUAL GROSS WEIGHT AGW ALL GOING WELL AH AFTER HATCH AHD AHEAD AHL AUSTRALIAN HOLD LADDERS AHTS ANCHOR HANDLING TUD AND SUPPLY VESSEL AIS AUTOMATIC IDENTIFICATION SYSTEM ALERT AUTOMATIC LIFE-SAVING EMERGENCY RADIO TRANSMITTER ALRS ADMIRALTY LIST OF RADIO SIGNALS ALT ALTERNATING AM ABOVE MENTIONED AM AIR MAIL AMSL ABOVE MEAN SEA LEVEL AMT AMOUNT AMVER AUTOMATED MUTUAL ASSISTANCE VESSEL RESCUE SYSTEM AMWELSH AMERICANISED WELSH COAL CHARTER PARTY ANERA ASIA-NORTH AMERICA WESTBOUND RATE AGREEMENT ANOP -

Cargo-Handling Equipment on Board and in Port

Unit 16 CARGO-HANDLING EQUIPMENT ON BOARD AND IN PORT Basic terms cargo-handling equipment front/side loader cargo gear van carrier handling facilities transtainer lifting gear container crane / portainer conveyor belt transit shed elevator warehouse pumping equipment cranes: derrick dockside crane, fork lift truck quay crane, mobile crane container crane straddle carrier gantry crane, tractor deck crane tug-master (ship’s) cargo gear The form of cargo-handling equipment employed is basically determined by the nature of the actual cargo and the type of packing used. The subject of handling facilities raises the important question of mechanization. BULK CARGO HANDLING EQUIPMENT So far as dry bulk cargoes are concerned, handling facilities may be in the form of power-propelled conveyor belts, usually fed at the landward end by a hopper (a very large container on legs) or grabs, which may be magnetic for handling ores, fixed to a high capacity travel1ing crane or travel1ing gantries. These gantries move not only parallel to the quay, but also run back for considerable distances, and so cover a large stacking area, and are able to plumb the ship's hold. These two types of equipment are suitable for handling coal and ores. In the case of bulk sugar or when the grab is also used, the sugar would be discharged into a hopper, feeding by gravity a railway wagon or road vehicle below. Elevators (US) or silos are normally associated with grain. They may be operated by pneumatic suction which sucks the grain out of the ship's hold. SHIP UNLOADERS FRONT LOADER BELT CONVEYOR HOPPER HOPPER SILO / ELEVATOR GRAB TYPE UNLOADERS LOADING BOOM LIQUID CARGO HANDLING EQUIPMENT The movement of liquid bulk cargo , crude oil and derivatives, from the tanker is undertaken by means of pipelines connected to the shore-based storage tanks. -

An Appraisal of Demurrage Policies and Charges of Maritime Operators

An Appraisal of Demurrage Policies and Charges of Maritime Operators in Nigerian Seaport Terminals: the Shipping Industry and Economic Implications Procjena politika i trošarina pomorskih operatora na prekostojnice u nigerijskim morskim terminalima: implikacije na brodarstvo i ekonomiju Obed Ndikom Nwokedi, Theophilus C. Sodiq, Olusegun Buhari Department of Maritime Management Department of Maritime Management Department of Maritime Management Technology Technology Technology Federal University of Technology Federal University of Technology Federal University of Technology Owerri Owerri Owerri e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] Kenneth Okeke Okechukwu Department of Maritime Management DOI 10.17818/NM/2017/3.3 Technology UDK 656.615:330.13 Federal University of Technology Review / Pregledni rad Owerri Paper accepted / Rukopis primljen: 27. 2. 2017. Summary This research evaluated the demurrage policies and charges of selected shipping KEY WORDS companies and terminal operators in the Lagos ports and the implications in the demurrage economy and shipping industry in Nigeria. It adopted the survey approach to gather policies data from the dominant container operators (carriers) and the terminal operators. maritime operators Demurrage duration and categorization of the demurrage periods and charges for each seaports period by the selected operators were collected and compared using the statistical tool shipping industry of analysis of variance to determine if there are differences among the charges and charging systems. It was found that, significant differences do not exist in the average rate of demurrage charges per container per day among the shipping companies and terminal operators in Lagos seaports. The study also found that there is no significant difference in the average amount charged as demurrage among the shipping companies and terminal operators in the three differing periods of demurrage duration in Lagos ports, Nigeria. -

Dangerous Solid Cargoes in Bulk

A selection of articles previously Dangerous solid published by Gard AS cargoes in bulk DRI, nickel and iron ores 3 Contents Carriage of dangerous cargo - Questions to ask before you say yes .............................................. 4 Understanding the different direct reduced iron products ................................................................ 7 Carriage of Direct Reduced Iron (DRI) by Sea - Changes to the IMO Code of Safe Practice for Solid Bulk Cargoes ....................................................................................................... 8 The dangers of carrying Direct Reduced Iron (DRI) .......................................................................... 11 Information required when offered a shipment of Iron fines that may contain DRI (C) ................ 12 Liquefaction of unprocessed mineral ores - Iron ore fines and nickel ore ...................................... 14 Intercargo publishes guide for the safe loading of nickel ore ......................................................... 18 Shifting solid bulk cargoes .................................................................................................................. 19 Cargo liquefaction - An update .......................................................................................................... 22 Cargo liquefaction problems – sinter feed from Brazil ..................................................................... 26 Liquefaction of cargoes of iron ore ................................................................................................... -

Cargo Liens for Unpaid Hire and Freight Due Under a Time Or Voyage Charterparty

Cargo liens for unpaid hire and freight due under a time or voyage charterparty During periods in which the global shipping economy is volatile, the likelihood of unpaid freight or hire occurs with higher frequency. Recently, the Club has witnessed charterers facing difficulty in meeting their obligation to pay freight due under a charterparty. In such circumstances, the shipowner may want to know if he is able to exercise a lien on the cargo until he has been paid the freight or hire due under the charterer. There must be a right of lien in the charterparty By Gho Sze Kee, Deputy Claims Manager The shipowner needs to determine if the charterparty will grant him a possessory lien over the cargo for the unpaid freight and As such, where the bill of lading incorporates a lien clause for unpaid hire. The more clearly a lien clause is drafted, the easier it is for the hire (as opposed to freight), the shipowners then has a right under shipowner to determine the scope of the lien clause and therefore the bill of lading to lien the cargo regardless of whether it is owned exercise his possessory lien for the unpaid freight or hire. by the charterers. Examples of widely drafted lien clauses that extend to and protect the shipowners right to lien, are clause 8 of GENCON 1994 Clause 1 of CONGENBILL All terms and conditions, liberties and exceptions of the Charter charterparty and clause 23 of NYPE 93. Party, dated as overleaf, including the Law and Arbitration Only when hire or freight under a charterparty becomes ‘due’ and Clause, are herewith incorporated.