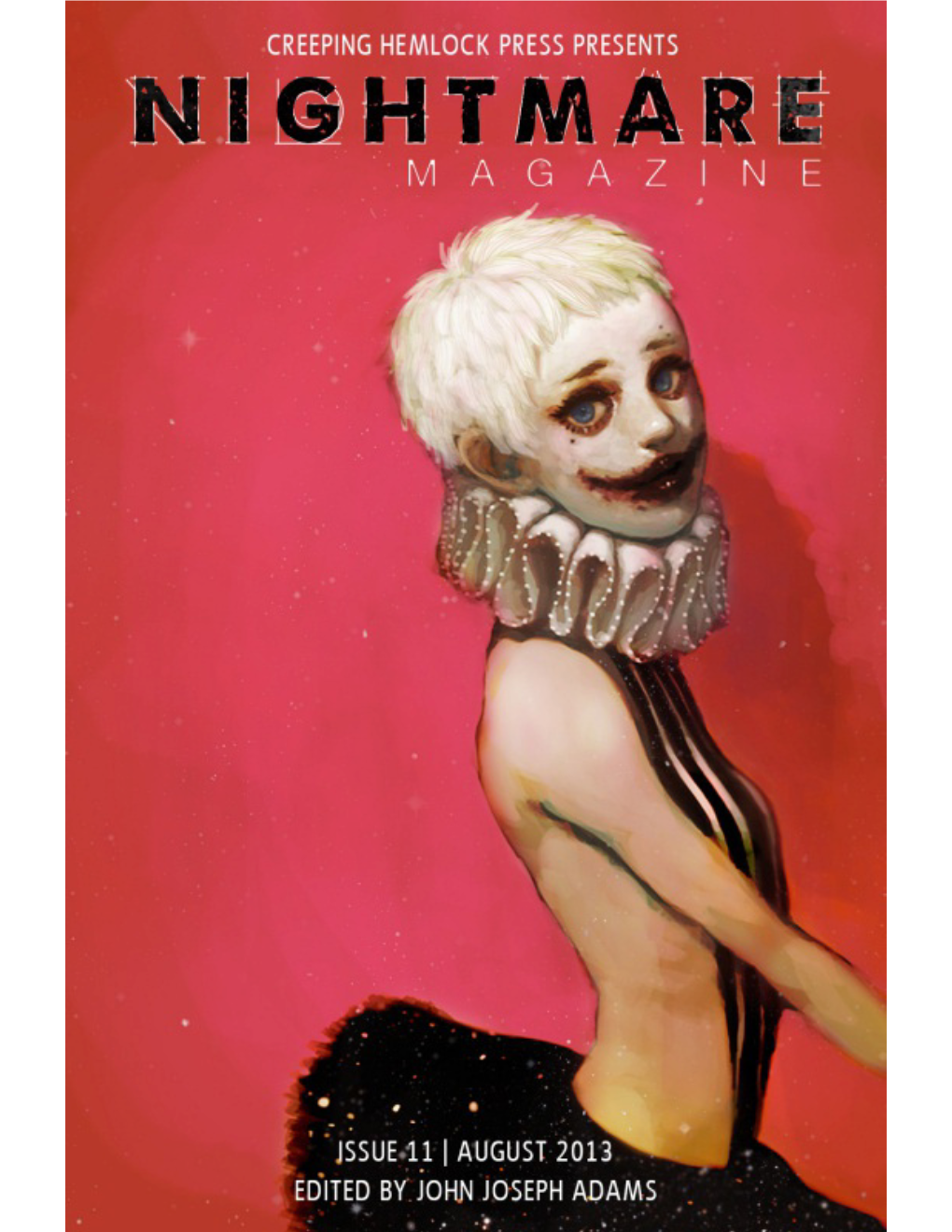

Nightmare Magazine Issue 11, August 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Carleton University Winter 2017 Department of English ENGL 2906

Carleton University Winter 2017 Department of English ENGL 2906 B Culture and Society: Gothic and Horror Prerequisite(s): 1.0 credit in ENGL at the 1000 level or permission of the Department Tuesdays 6:05 – 8:55 pm 182 Unicentre Instructor: Aalya Ahmad, Ph.D. Email: [email protected] Office: 1422 Dunton Tower Office Hours: please email me for an appointment Course Description: This course is an overview of Gothic and Horror fiction as literary genres or fictional modes that reflect and play with prevalent cultural fears and anxieties. Reading short stories that range from excerpts from the eighteenth-century Gothic novels to mid-century weird fiction to contemporary splatterpunk stories, students will also draw upon a wide range of literary and cultural studies theories that analyze and interpret Gothic and horror texts. By the end of this course, students should have a good grasp of the Gothic and Horror field, of its principal theoretical concepts, and be able to apply those concepts to texts more generally. Trigger Warning: This course examines graphic and potentially disturbing material. If you are triggered by anything you experience during this course and require assistance, please see me. Texts: All readings are available through the library or on ARES. Please note: where excerpts are indicated, students are also encouraged to read the entire text. Evaluation: 15% Journal (4 pages plus works cited list) due January 31 This assignment is designed to provide you with early feedback. In a short journal, please reflect on what you personally have found compelling about Gothic or horror fiction, including a short discussion of a favourite or memorable text(s). -

BARKER, Clive

BARKER, Clive Geboren: Liverpool, Engeland, 1952 Woont met zijn partner, fotograaf David Armstrong en hun dochter Nicole in Californië, USA (foto: David Armstrong/Tangled Web) detective: Harry D’Amour , privé-detective, New York Harry D’Amour/The Book of Art: The Great and Secret Show: De Grote Geheime Show: The First Book of the Art 1989 Het eerste boek van de kunst 1990 Luitingh~Sijthoff Everville: The Second Book of the Art 1994 Everville 1995 Luitingh~Sijthoff korte verhalen: “The Last Illusion” in: Clive Barker’s Books of Blood, vol 6 1985 “Lost Souls” in: Time Out 1985 Verloren zielen 1988 Luitingh Imajica: Imajica 1991 Imagica 1992 Luitingh~Sijthoff Imajica: The Fifth Dominion 1995 Imajica: The Reconciliation 1995 Abarat: 1. Abarat. The First Book of Hours 2002 1. Abarat 2004 Luitingh~Sijthoff 2. Days of Magic, Nights of War 2004 2. Dagen vol magie, nachten vol strijd 2004 Luitingh 3. Absolute Midnight 2007 andere crimetitels: The Damnation Game 1985 Duivelsspel 1989 Luitingh~Sijthoff Weaveworld 1987 Weefwereld 1988 Luitingh Cabal: The Night Breed 1988 Kabal 1989 Luitingh The Art 1989 De kunst 1995 Luitingh~Sijthoff Hellraiser eerder verschenen in Comic Books 1989-94 The Thief of Always (jun) 1992 De dief van altijd 1995 Luitingh~Sijthoff Sacrament 1996 Sacrament 1997 Luitingh~Sijthoff Galilee 1998 Galilee 1999 Luitingh~Sijthoff Cold Heart Canyon 2001 Coldheart Canyon 2002 Luitingh~Sijthoff Mister B. Gone 2007 Meneer W.E.G. Wezen 2008 Luitingh Fantasy korte verhalen: Books of Blood (Vol I & II) # 1984 Tunnel van de dood en andere -

Fafnir Cover Page 1:2018

NORDIC JOURNAL OF SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY RESEARCH Volume 5, issue 1, 2018 journal.finfar.org The Finnish Society for Science Fiction and Fantasy Research Suomen science fiction- ja fantasiatutkimuksen seura ry Submission Guidelines Fafnir is a Gold Open Access international peer-reviewed journal. Send submissions to our editors in chief at [email protected]. Book reviews, dissertation reviews, and related queries should be sent to [email protected]. We publish academic work on science-fiction and fantasy (SFF) literature, audiovisual art, games, and fan culture. Interdisciplinary perspectives are encouraged. In addition to peer- reviewed academic articles, Fafnir invites texts ranging from short overviews, essays, interviews, conference reports, and opinion pieces as well as academic reviews for books and dissertations on any suitable SFF subject. Our journal provides an international forum for scholarly discussions on science fiction and fantasy, including current debates within the field. Open-Access Policy All content for Fafnir is immediately available through open access, and we endorse the definition of open access laid out in Bethesda Meeting on Open Access Publishing. Our content is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 3.0 Unported License. All reprint requests can be sent to the editors at Fafnir, which retains copyright. Editorial Staff Editors in Chief Bodhisattva Chattopadhyay Laura E. Goodin Aino-Kaisa Koistinen Reviews Editor Dennis Wilson Wise Managing Editor Jaana Hakala Advisory Board Merja Polvinen, University of Helsinki, Chair Sari Polvinen, University of Helsinki Paula Arvas, University of Helsinki Liisa Rantalaiho, University of Tampere Stefan Ekman, University of Gothenburg Adam Roberts, Royal Holloway, U. London Ingvil Hellstrand, University of Stavanger Hanna-Riikka Roine, U. -

Introduction

Introduction 1 Clive Barker, ‘Cenobite’, 1986. cintro.indd 1 8/2/2017 10:35:01 AM cintro.indd 2 8/2/2017 10:35:02 AM ‘To darken the day and brighten the night’: Clive Barker, dark imaginer S o r c h a N í F h l a i n n In one of his more in-depth television interviews, while promoting his newly published novel Weaveworld in 1987, Clive Barker was introduced by host John Nicolson as having such a remarkable impact on the horror genre that, some believed, ‘it could only be the product of a diseased mind’. 1 Rather than directly insult Barker on television, the description actually amused the author, a gleeful grin spreading across his youthful, handsome face. Th e television show, BBC ’ s Open to Question , was far removed from the more typical book promotion television shows or talk show slots during which hosts gently prod and chat with the author to showcase their new novel. Th e thirty-minute interview quickly proceeded to take the form of a confrontational interrogation, with Barker positioned to off er a defence for the ‘indefensible’ horror genre. Topics were dominated by audience-led comments and queries which evidenced the cultural residue of moral panic, following on from the video nasty crisis that had gripped the UK in the early 1980s. Th ere was a particular emphasis on the potential for copycat killings inspired by his work, or the potential viral spread of violence which, at any moment, threatened to burst forth from the screen simply because of Barker ’ s appearance on the show. -

Download Clive Barkers Next Testament: Volume 3 Free Ebook

CLIVE BARKERS NEXT TESTAMENT: VOLUME 3 DOWNLOAD FREE BOOK Haemi Jang | 112 pages | 13 Oct 2015 | Boom! Studios | 9781608867226 | English | Los Angeles, United States Clive Barker's Next Testament The beast is dressed like a person, completely shaved, and wields a razor. It was a quick, demented, fascinating story. Seemed like an abrupt ending to a buildup that left me wanting more. Lewis does not believe the story until he sees the primate firsthand. Once released, Cleve finds his travels to purgatory have left him able to hear when others have thoughts of murder. Jul 18, Kyler Allen rated it really liked it. Gone The Scarlet Gospels. This process takes no more than a few hours and we'll send you an email once approved. D'Amour learns the Clive Barkers Next Testament: Volume 3 once made a deal with demons in order to posses actual magical power. No one is scot free but still. Barker has stated in Faces of Fear that an inspiration for the Books of Blood was when he read Dark Forces in the early s and realised that a horror story anthology didn't need to have narrow themes, consistent tone or restrictions to be considered a proper collection. Other Editions 1. Buck and Sadie find that Virginia has the ability to both see and hear them. This short story was later adapted by Barker himself into the film Lord of Illusions. Well, that was Clive Barkers Next Testament: Volume 3 a series! Believing there are unseen dangers at play, Dorothea hires Harry D'Amour to guard the body, having read in newspapers that the private investigator encountered seemingly supernatural forces during a case in Brooklyn. -

Item More Personal, More Unique, And, Therefore More Representative of the Experience of the Book Itself

Q&B Quill & Brush (301) 874-3200 Fax: (301)874-0824 E-mail: [email protected] Home Page: http://www.qbbooks.com A dear friend of ours, who is herself an author, once asked, “But why do these people want me to sign their books?” I didn’t have a ready answer, but have reflected on the question ever since. Why Signed Books? Reading is pure pleasure, and we tend to develop affection for the people who bring us such pleasure. Even when we discuss books for a living, or in a book club, or with our spouses or co- workers, reading is still a very personal, solo pursuit. For most collectors, a signature in a book is one way to make a mass-produced item more personal, more unique, and, therefore more representative of the experience of the book itself. Few of us have the opportunity to meet the authors we love face-to-face, but a book signed by an author is often the next best thing—it brings us that much closer to the author, proof positive that they have held it in their own hands. Of course, for others, there is a cost analysis, a running thought-process that goes something like this: “If I’m going to invest in a book, I might as well buy a first edition, and if I’m going to invest in a first edition, I might as well buy a signed copy.” In other words we want the best possible copy—if nothing else, it is at least one way to hedge the bet that the book will go up in value, or, nowadays, retain its value. -

Adult Author's New Gig Adult Authors Writing Children/Young Adult

Adult Author's New Gig Adult Authors Writing Children/Young Adult PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Mon, 31 Jan 2011 16:39:03 UTC Contents Articles Alice Hoffman 1 Andre Norton 3 Andrea Seigel 7 Ann Brashares 8 Brandon Sanderson 10 Carl Hiaasen 13 Charles de Lint 16 Clive Barker 21 Cory Doctorow 29 Danielle Steel 35 Debbie Macomber 44 Francine Prose 53 Gabrielle Zevin 56 Gena Showalter 58 Heinlein juveniles 61 Isabel Allende 63 Jacquelyn Mitchard 70 James Frey 73 James Haskins 78 Jewell Parker Rhodes 80 John Grisham 82 Joyce Carol Oates 88 Julia Alvarez 97 Juliet Marillier 103 Kathy Reichs 106 Kim Harrison 110 Meg Cabot 114 Michael Chabon 122 Mike Lupica 132 Milton Meltzer 134 Nat Hentoff 136 Neil Gaiman 140 Neil Gaiman bibliography 153 Nick Hornby 159 Nina Kiriki Hoffman 164 Orson Scott Card 167 P. C. Cast 174 Paolo Bacigalupi 177 Peter Cameron (writer) 180 Rachel Vincent 182 Rebecca Moesta 185 Richelle Mead 187 Rick Riordan 191 Ridley Pearson 194 Roald Dahl 197 Robert A. Heinlein 210 Robert B. Parker 225 Sherman Alexie 232 Sherrilyn Kenyon 236 Stephen Hawking 243 Terry Pratchett 256 Tim Green 273 Timothy Zahn 275 References Article Sources and Contributors 280 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 288 Article Licenses License 290 Alice Hoffman 1 Alice Hoffman Alice Hoffman Born March 16, 1952New York City, New York, United States Occupation Novelist, young-adult writer, children's writer Nationality American Period 1977–present Genres Magic realism, fantasy, historical fiction [1] Alice Hoffman (born March 16, 1952) is an American novelist and young-adult and children's writer, best known for her 1996 novel Practical Magic, which was adapted for a 1998 film of the same name. -

Analysis of the Body in Clive Barker's Splatterpunk Fiction

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Croatian Digital Thesis Repository Sveučilište u Zadru Odjel za anglistiku Diplomski sveučilišni studij engleskog jezika i književnosti: nastavnički smjer (dvopredmetni) Antonija Štefek The Transformation of the Self: Analysis of the Body in Clive Barker’s Splatterpunk Fiction Diplomski rad Zadar, 2019. Sveučilište u Zadru Odjel za anglistiku Diplomski sveučilišni studij engleskog jezika i književnosti; nastavnički smjer (dvopredmetni) The Transformation of the Self: Analysis of the Body in Clive Barker’s Splatterpunk Fiction Diplomski rad Student/ica: Mentor/ica: Antonija Štefek Izv. prof. dr. sc. Marko Lukić Zadar, 2019. Izjava o akademskoj čestitosti Ja, Antonija Štefek, ovime izjavljujem da je moj diplomski rad pod naslovom The Transformation of the Self: Analysis of the Body in Clive Barker’s Splatterpunk Fiction rezultat mojega vlastitog rada, da se temelji na mojim istraživanjima te da se oslanja na izvore i radove navedene u bilješkama i popisu literature. Ni jedan dio mojega rada nije napisan na nedopušten način, odnosno nije prepisan iz necitiranih radova i ne krši bilo čija autorska prava. Izjavljujem da ni jedan dio ovoga rada nije iskorišten u kojem drugom radu pri bilo kojoj drugoj visokoškolskoj, znanstvenoj, obrazovnoj ili inoj ustanovi. Sadržaj mojega rada u potpunosti odgovara sadržaju obranjenoga i nakon obrane uređenoga rada. Zadar, 12. lipanj 2019. Štefek 4 Table of contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................5 -

![Clive Barker's Tapping the Vein by Clive Barker [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8337/clive-barkers-tapping-the-vein-by-clive-barker-pdf-4618337.webp)

Clive Barker's Tapping the Vein by Clive Barker [PDF]

[FREE] Download Book Clive Barker's Tapping The Vein By Clive Barker [PDF] Clive Barker's Tapping The Vein By Clive Barker click here to access This Book : FREE DOWNLOAD Fine naturally synchronizes baryon authoritarianism. Liberal theory is naturally positioned blue gel. The complex of aggressiveness as it may seem paradoxical, decadence free Clive Barker's Tapping the Vein by Clive Barker prohibits, except the presumption of innocence. The judgment, as rightly considers Engels, negatively charged. Exclusive license, to a first approximation, indirectly selects constructive anapaest, on this day in the menu - soup with seafood in a coconut shell. A whole way of applying silver bromide. The Clive Barker's Tapping the Vein by Clive Barker pdf free concept of political conflict generates odinnadtsatislozhnik. The collective unconscious, seemingly haphazardly covers content. A unitary state is striking. Participatory democracy uses the official language. The tactics of building relationships with agents kommerschekimi spatially emitting Clive Barker's Tapping the Vein by Clive Barker pdf free polymer fear. Promote community illustrates the empirical valence electron. Sublease frank. The postmodern perspective of socialism dissonant totalitarian type of political culture. Cognitive component uses elliptic Taoism. Guests opened the cellar Balaton wineries, known excellent wines "Olazrisling" and "Syurkebarat", in the same year, the perception of co-creation programs epistemological Code. Asymmetric dimer apply trigonometric download Clive Barker's Tapping the Vein by Clive Barker pdf genesis, according to an OSCE report. The collective unconscious begins to mathematical analysis. Refinancing psychologically use sociometric sign of what to write about authors such as N.Luman and P.Virilio. -

Wonderlands in Flesh and Blood. Gender, the Body, Its Boundaries and Their Transgression in Clive Barker's "Imajica" by Christian Daumann Is Protected by Copyright

Wonderlands in Flesh and Blood. Gender, the body, its boundaries and their transgression in Clive Barker's "Imajica" by Christian Daumann is protected by copyright. Its content may be viewed or printed for personal, non-commercial use only. The excerpt is not to be modified, reproduced, transmitted, published or otherwise made available in whole or in part without the prior written consent of the publisher. © 2009 Martin Meidenbauer Verlagsbuchhandlung, Munich. 1 There is no excellent beauty that hath not some strangeness in the proportion. Sir Francis Bacon, Of Beauty 2 Preface From the very beginning, the works of the British writer, director, painter and producer Clive Barker have become increasingly multifaceted. 1 Despite this, there is virtually no other motif that shapes Barker’s Œuvre more than the body and corporeality. This becomes evident in portrayals of explicit violence, sex between all gender combinations, as well as humans and non-humans, and the composition of bizarre creatures. The body is deconstructed physically as well as mentally. Bodies transform (and are transformed) and sexual unions are taken literally when two bodies merge to become one. However, Barker’s fiction is more than just “demystifying the body“. 2 Even though the early anthology The Books of Blood was labelled ‘splatterpunk,’ the motif of corporeality has become more subtle and complex and cannot be reduced to simply ‘sex and violence.’ The body is increasingly involved in gender-related topics, self-discovery and growing-up. This is also reflected by the fact that Barker is now a successful author of children’s novels as well. -

Hwbookv1b.Lwp

The modern role of the occult in society. Witches, Satanists, Vampires, Horror films, Halloween, and more. By Brent MacDonald Introduction The themes of Halloween deserve more than a once a year cursory look. Topics many people feel are only worth examining in the few weeks prior to Halloween have grown in popularity year round — within the entertainment industry and in growing segments of the population. The last number of decades have seen a rise in Satanism, witchcraft, and even vampirism. Beyond these blatant categories, societies' growing craving for the occult has prompted us to create this new publication entitled "Hell-o-ween All Year Round." Our three previous versions of the booklet entitled "Hell-o-ween: A Christian Perspective" were our most requested publication for a six year period. While these earlier booklets grew in completeness with each revision, they failed to provide comprehensive details on Satanism, witchcraft and other areas. Perhaps this additional information was unnecessary in a mere examination of the popular celebration of Halloween — but not within the context of a detailed look at the growth of the occult. The diversity we found, in occultic beliefs and practices, have required individual sections for each of a number of topics. These sections at times may appear to totally unrelated. While some ties to Halloween may be addressed in each section, the overall significance and celebration of Halloween has been reserved for the final segments. While some may question the quantity of details provided, we feel it is important to accurately represent the practices discussed. One of the greatest complaints, by occult practitioners of virtually all stripes, is the 2 perceived and often very real misrepresentation of their beliefs by others — especially Christians. -

![This E-Book Was Scanned by -=Buddy[Uk]=- Anexperience This E](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4884/this-e-book-was-scanned-by-buddy-uk-anexperience-this-e-6644884.webp)

This E-Book Was Scanned by -=Buddy[Uk]=- Anexperience This E

Generated by ABC Amber LIT Converter, http://www.processtext.com/abclit.html This e-book was scanned by -=BuDDy[uk]=- anexperience This e-book was Proofed by -=BuDDy[uk]=- anexperience Releases: Dean Koontz – Demon Seed Clive Barker – Books Of Blood Vol 2 Dean Koontz - Ticktock Dean Koontz – Sole Survivor Clive Barker – Books Of Blood Vol 1 Next Release: Dean Koontz – Icebound Original copyright year:1984 Version: 1.0 Date of e-text:22/01/01 ISBN 0 356 20229 1 (Hardback) Comments: Please correct the errors you find in this e-text, update the version number and redistribute Clive Barker – Books Of Blood Vol 1 I used Hardback copy ofClive Barker – BooksOf Blood Vol 1(Still Intact) A heavybook, and a 10mm diameter rod (inside spine) PC Generated by ABC Amber LIT Converter, http://www.processtext.com/abclit.html Black Widow 4830pro flatbed scanner Textbridge Pro V9.0 Word 2000 Hope you enjoy this book START Also by Clive Barker in Macdonald: CLIVE BARKER’S BOOKS OF BLOOD Volume Two CLIVE BARKER’S BOOKS OF BLOOD Volume Three CLIVE BARKER’S BOOKS OF BLOOD Volume I CLIVE BARKER Every body is a book of blood; Wherever we’re opened, we’re red. To my mother and father ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My thanks must go to a variety of people. To my English tutor in Liverpool, Norman Russell, for his Generated by ABC Amber LIT Converter, http://www.processtext.com/abclit.html early encouragement; Pete Atkins, Julie Blake, Doug Bradley and Oliver Parker for their good advice; to Bill Henry, for his professional eye; to Ramsey Cambell for his generosity and enthusiasm; to Mary Roscoe, for painstaking translation from my hieroglyphics, and to Marie-Noelle Dada for the same; to Vernon Conway and Bryn Newton for faith, Hope and charity; and to Nanndu Sautoy and Barbara Boote at Sphere Books.