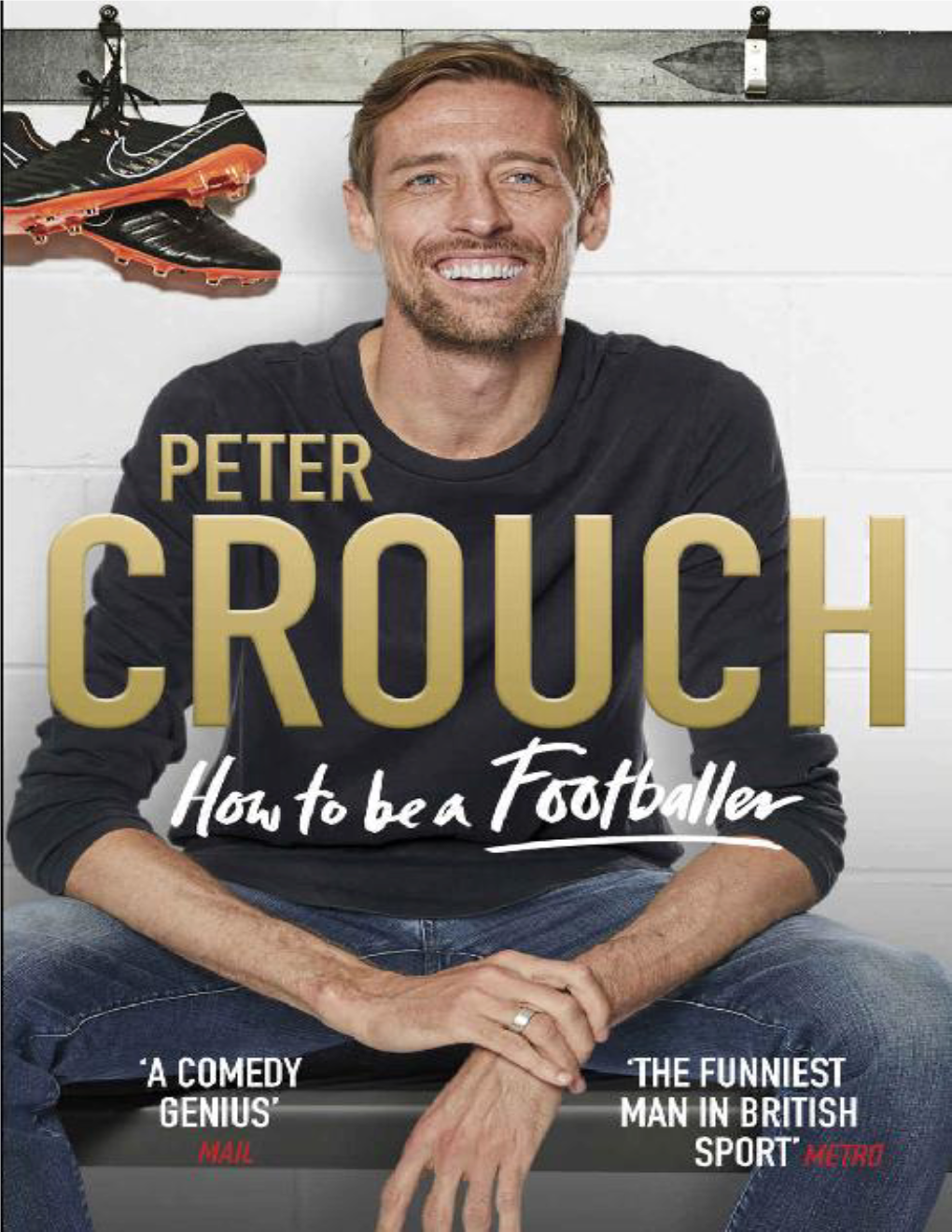

How to Be a Footballer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Save of the Season?

THE MAGAZINE FOR THE GOALKEEPING PROFESSION £4.50 TM AUTUMN 2011 Craig GORDON SAVE OF THE SEASON? The greatest saves of all time GK1 looks at the top 5 saves in the history of the game Coaching Corner The art of saving penalties Equipment Exclusive interviews with: Precision, Uhlsport & Sells Goalkeeper Products Gordon Banks OBE Gary Bailey Kid Gloves Kasper Schmeichel The stars of the future On the Move Also featuring: Summary of the latest GK transfers Alex McCarthy, Reading FC John Ruddy, Norwich City Business Pages Alex Smithies, Huddersfield Town Key developments affecting the professional ‘keeper Bob Wilson OBE Welcome to The magazine exclusively for the professional goalkeeping community. Welcome to the Autumn edition of suppliers, coaches and managers alike we are Editor’s note GK1 – the magazine exclusively for the proud to deliver the third issue of a magazine professional goalkeeping community. dedicated entirely to the art of goalkeeping. Andy Evans / Editor-in-Chief of GK1 and Chairman of World In Motion ltd After a frenetic summer of goalkeeper GK1 covers the key elements required of transfer activity – with Manchester a professional goalkeeper, with coaching United, Liverpool, Chelsea and features, equipment updates, a summary Tottenham amongst those bolstering of key transfers and features covering the their goalkeeping ranks – our latest uniqueness of the goalkeeper to a football edition of GK1 brings you a full and team. The magazine also includes regular comprehensive round-up of all the features ‘On-the-Move’, summarising all the ‘keepers who made moves in the Summer latest transfers involving the UK’s professional 2011 transfer window. -

Graham Budd Auctions Sotheby's 34-35 New Bond Street Sporting Memorabilia London W1A 2AA United Kingdom Started 22 May 2014 10:00 BST

Graham Budd Auctions Sotheby's 34-35 New Bond Street Sporting Memorabilia London W1A 2AA United Kingdom Started 22 May 2014 10:00 BST Lot Description An 1896 Athens Olympic Games participation medal, in bronze, designed by N Lytras, struck by Honto-Poulus, the obverse with Nike 1 seated holding a laurel wreath over a phoenix emerging from the flames, the Acropolis beyond, the reverse with a Greek inscription within a wreath A Greek memorial medal to Charilaos Trikoupis dated 1896,in silver with portrait to obverse, with medal ribbonCharilaos Trikoupis was a 2 member of the Greek Government and prominent in a group of politicians who were resoundingly opposed to the revival of the Olympic Games in 1896. Instead of an a ...[more] 3 Spyridis (G.) La Panorama Illustre des Jeux Olympiques 1896,French language, published in Paris & Athens, paper wrappers, rare A rare gilt-bronze version of the 1900 Paris Olympic Games plaquette struck in conjunction with the Paris 1900 Exposition 4 Universelle,the obverse with a triumphant classical athlete, the reverse inscribed EDUCATION PHYSIQUE, OFFERT PAR LE MINISTRE, in original velvet lined red case, with identical ...[more] A 1904 St Louis Olympic Games athlete's participation medal,without any traces of loop at top edge, as presented to the athletes, by 5 Dieges & Clust, New York, the obverse with a naked athlete, the reverse with an eleven line legend, and the shields of St Louis, France & USA on a background of ivy l ...[more] A complete set of four participation medals for the 1908 London Olympic -

Theory of the Beautiful Game: the Unification of European Football

Scottish Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 54, No. 3, July 2007 r 2007 The Author Journal compilation r 2007 Scottish Economic Society. Published by Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK and 350 Main St, Malden, MA, 02148, USA THEORY OF THE BEAUTIFUL GAME: THE UNIFICATION OF EUROPEAN FOOTBALL John Vroomann Abstract European football is in a spiral of intra-league and inter-league polarization of talent and wealth. The invariance proposition is revisited with adaptations for win- maximizing sportsman owners facing an uncertain Champions League prize. Sportsman and champion effects have driven European football clubs to the edge of insolvency and polarized competition throughout Europe. Revenue revolutions and financial crises of the Big Five leagues are examined and estimates of competitive balance are compared. The European Super League completes the open-market solution after Bosman. A 30-team Super League is proposed based on the National Football League. In football everything is complicated by the presence of the opposite team. FSartre I Introduction The beauty of the world’s game of football lies in the dynamic balance of symbiotic competition. Since the English Premier League (EPL) broke away from the Football League in 1992, the EPL has effectively lost its competitive balance. The rebellion of the EPL coincided with a deeper media revolution as digital and pay-per-view technologies were delivered by satellite platform into the commercial television vacuum created by public television monopolies throughout Europe. EPL broadcast revenues have exploded 40-fold from h22 million in 1992 to h862 million in 2005 (33% CAGR). -

Semangat Berolahraga

SEMANGAT BEROLAHRAGA | Tottenham vs Chelsea: Peluang Rusak Sejarah Copyright Nana Yuana [email protected] http://nanayuana.staff.ipb.ac.id/2011/12/21/tottenham-vs-chelsea-peluang-rusak-sejarah/ Tottenham vs Chelsea: Peluang Rusak Sejarah Sebuah laga menarik akan berlangsung jelang Perayaan Natal. Dua klub asal Kota London yang sedang berada di papan atas, Tottenham Hotspur dan Chelsea akan saling beradu, Kamis (22/12). Pertandingan nanti jelas cukup menentukan bagi kedua tim. Baik Spurs dan The Blues kini hanya terpisah satu strip di klasemen sementara Premier League. Spurs diperingkat ketiga dan Chelsea tepat di bawahnya dengans selisih dua angka. Keuntungan kini jelas berada di pihak tuna rumah, Tottenham. Jika menilik sejarah 11 laga terakhir di Premier League, tidak ada satu pun tim tamu yang berhasil membawa pulang kemenangan pada duel kedua tim ini. page 1 / 3 SEMANGAT BEROLAHRAGA | Tottenham vs Chelsea: Peluang Rusak Sejarah Copyright Nana Yuana [email protected] http://nanayuana.staff.ipb.ac.id/2011/12/21/tottenham-vs-chelsea-peluang-rusak-sejarah/ Namun, semua itu hanya catatan sejarah belaka. Sebab, kondisi The Lilywhites saat ini cukup mengkhawatirkan. Sayap lincah Aaron Lennon dipastikan absen karena cedera. Sayap lain yakni Gareth Bale mungkin bisa bermain namun dengan kondisi tidak 100 persen pascasembuh dari cedera. Sedangkan kondisi The Blues masih lebih baik. Hanya Michael Essien, David Luiz dan Josh McEachran yang tidak bisa tampil. Dengan begitu kesempatan tim tamu untuk merusak sejarah 11 laga terakhir cukup terbuka lebar. (Okky) STATISTIK PERTEMUAN - Kedua tim telah melakoni 132 laga di segala ajang. Chelsea masih unggul dengan 56 kemenangan, berbanding 46 kemenangan milik Spurs. -

Marco Sanna, Il Guerriero Ichnuso Di Claudio Nucci 27 Marzo 2021 – 11:38

1 “Album dei ricordi blucerchiati”: Marco Sanna, il guerriero ichnuso di Claudio Nucci 27 Marzo 2021 – 11:38 Genova. Sardegna e Liguria, si interfacciano da secoli sul mare; sono due popoli, che hanno nel proprio background una convivenza tra pescatori e contadini, magari alternando un lavoro all’altro, a seconda delle stagioni… ecco il perché di una simbiosi ed empatia fra genovesi e sardi, tali da affinare caratteristiche culturali simili. Facile, quindi, che l’un l’altro possano trovarsi bene, quando le opportunità della vita li portano a “giocare in trasferta”… E’ il caso di Marco Sanna, sardo nel profondo dell’anima, ma che, nei tre anni passati nellaSampdoria, ha saputo integrarsi perfettamente nella quotidianità della vita genovese. Piedi ben radicati a terra, Sanna trova nel Tempio il suo trampolino di lancio, per farsi, giovanissimo, un nome in Serie C2 e non accusa il triplice salto di categoria, quando a 23 anni, dopo 6 anni di gavetta, lo chiama il Cagliari del presidente Cellino e nemmeno si spaventa al primo incontro, in sede, con il dirigenteGigi Riva, il mitico ‘Rombo di tuono’, non solo il più forte attaccante della storia italiana, ma autentical’ icona rossoblù. In quel Cagliari, il campione è Enzo Francescoli (73 partite e 17 goal con ‘la celeste uruguaja’), ma l’anima della squadra è rappresentata dai“Quattro mori”, quelli della bandiera dell’isola: un poker di “volti bendati”, costituito da capitanGianfranco Matteoli, Vittorio Pusceddu, Gianluca Festa ed appuntoMarco Sanna: un quadrilatero di ferro, capace di incarnare lo spirito sardo. E’ Carlo Mazzone, a farlo esordire in Coppa Italia, contro il Milan (in uno 0-3, che vede in campo Van Basten, Rijkaard e Papin, ma non Gullit, costretto in panchina dalle regole di allora, che permettevano di scendere in campo, solo a tre dei quattro stranieri tesserati ed è sempre il grande “Sor Carletto” a lanciarlo anche in Serie A, in un Cagliari- Roma (vinto 1-0), mettendolo a marcare un certo Giuseppe Giannini, ex numero numero 10 della Nazionale azzurra… mica male per un esordiente. -

28 November 2012 Opposition

Date: 28 November 2012 Times Telegraph Echo November 28 2012 Opposition: Tottenham Hotspur Guardian Mirror Evening Standard Competition: League Independent Mail BBC Own goal a mere afterthought as Bale's wizardry stuns Liverpool Bale causes butterflies at both ends as Spurs hold off Liverpool Tottenham Hotspur 2 With one glorious assist, one goal at the right end, one at the wrong end and a Liverpool 1 yellow card for supposed simulation, Gareth Bale was integral to nearly Gareth Bale ended up with a booking for diving and an own goal to his name, but everything that Tottenham did at White Hart Lane. Spurs fans should enjoy it still the mesmerising manner in which he took this game to Liverpool will live while it lasts, because with Bale's reputation still soaring, Andre Villas-Boas longer in the memory. suggested other clubs will attempt to lure the winger away. The Wales winger was sufficiently sensational in the opening quarter to "He is performing extremely well for Spurs and we are amazed by what he can do render Liverpool's subsequent recovery too little too late -- Brendan Rodgers's for us," Villas-Boas said. "He's on to a great career and obviously Tottenham want team have now won only once in nine games -- and it was refreshing to be lauding to keep him here as long as we can but we understand that players like this have Tottenham's prodigious talent rather than lamenting the sick terrace chants in the propositions in the market. That's the nature of the game." games against Lazio and West Ham United. -

Silva: Polished Diamond

CITY v BURNLEY | OFFICIAL MATCHDAY PROGRAMME | 02.01.2017 | £3.00 PROGRAMME | 02.01.2017 BURNLEY | OFFICIAL MATCHDAY SILVA: POLISHED DIAMOND 38008EYEU_UK_TA_MCFC MatDay_210x148w_Jan17_EN_P_Inc_#150.indd 1 21/12/16 8:03 pm CONTENTS 4 The Big Picture 52 Fans: Your Shout 6 Pep Guardiola 54 Fans: Supporters 8 David Silva Club 17 The Chaplain 56 Fans: Junior 19 In Memoriam Cityzens 22 Buzzword 58 Social Wrap 24 Sequences 62 Teams: EDS 28 Showcase 64 Teams: Under-18s 30 Access All Areas 68 Teams: Burnley 36 Short Stay: 74 Stats: Match Tommy Hutchison Details 40 Marc Riley 76 Stats: Roll Call 42 My Turf: 77 Stats: Table Fernando 78 Stats: Fixture List 44 Kevin Cummins 82 Teams: Squads 48 City in the and Offi cials Community Etihad Stadium, Etihad Campus, Manchester M11 3FF Telephone 0161 444 1894 | Website www.mancity.com | Facebook www.facebook.com/mcfcoffi cial | Twitter @mancity Chairman Khaldoon Al Mubarak | Chief Executive Offi cer Ferran Soriano | Board of Directors Martin Edelman, Alberto Galassi, John MacBeath, Mohamed Mazrouei, Simon Pearce | Honorary Presidents Eric Alexander, Sir Howard Bernstein, Tony Book, Raymond Donn, Ian Niven MBE, Tudor Thomas | Life President Bernard Halford Manager Pep Guardiola | Assistants Rodolfo Borrell, Manel Estiarte Club Ambassador | Mike Summerbee | Head of Football Administration Andrew Hardman Premier League/Football League (First Tier) Champions 1936/37, 1967/68, 2011/12, 2013/14 HONOURS Runners-up 1903/04, 1920/21, 1976/77, 2012/13, 2014/15 | Division One/Two (Second Tier) Champions 1898/99, 1902/03, 1909/10, 1927/28, 1946/47, 1965/66, 2001/02 Runners-up 1895/96, 1950/51, 1988/89, 1999/00 | Division Two (Third Tier) Play-Off Winners 1998/99 | European Cup-Winners’ Cup Winners 1970 | FA Cup Winners 1904, 1934, 1956, 1969, 2011 Runners-up 1926, 1933, 1955, 1981, 2013 | League Cup Winners 1970, 1976, 2014, 2016 Runners-up 1974 | FA Charity/Community Shield Winners 1937, 1968, 1972, 2012 | FA Youth Cup Winners 1986, 2008 3 THE BIG PICTURE Celebrating what proved to be the winning goal against Arsenal, scored by Raheem Sterling. -

2016 Veth Manuel 1142220 Et

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Selling the People's Game Football's transition from Communism to Capitalism in the Soviet Union and its Successor State Veth, Karl Manuel Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 03. Oct. 2021 Selling the People’s Game: Football's Transition from Communism to Capitalism in the Soviet Union and its Successor States K. -

Man Utd Destroys City with Owen's Injury Time Goal 10:15, September 21, 2009

Man Utd destroys City with Owen's injury time goal 10:15, September 21, 2009 Manchester City showed a never-say-die attitude in their Sunday's derby by drawing level three times at Old Trafford, but Man United substitute Michael Owen wrecked their hope of snatching one point with a stunning goal in the stoppage time. Togo ace Emmanuel Adebayor's absence due to a three-match ban weakened City's attack, but Carlos Tevez was back to the pitch after resting for two weeks because of a knee injury. The Argentina striker was so aggressive in front of his ex-club that he stole the ball from a hesitating United keeper Ben Foster before assisting Gareth Barry to shot home in the 16th minutes. But it was only an equalizer as Wayne Rooney had put United ahead after two minutes. Being overlooked by United boss Sir Alex Ferguson in the previous two seasons, Tevez was thirsty for the derby after joining City this Summer. But he squandered his best chance of punishing United as he stroke the post in close range on the stroke of half-time, United managed to claimed an early lead again when Darren Fletcher nodded in Ryan Giggs's fine cross four minutes after the break, but Craig Bellamy fired home three minutes later to snuff United joy quickly. The defending champions then surged to attack ceaselessly, but Shay Given disappointed them by making two brilliant saves to Dimitar Berbatov's threatening headers and turned a powerful drive from Giggs over the top. It seemed that Ferguson was quite unsatisfied with the result and he replaced Belgarian Berbatov with Owen on 77 minutes. -

En Equipo. 33 (Sep.2008)

REVISTA OFICIAL de la Federación de Castilla y León de Fútbol Número 33 Julio 2008 CCDD NNuummaanncciiaa ddee SSoorriiaa,, aa lloo ggrraannddee LLaa AAssaammbblleeaa rraattiiffiiccaa aa MMaarrcceelliinnoo MMaattéé hhaassttaa 22001122 www.fcylf.es editorial Revista oficialdelaFederación CastillayLeóndeFútbol BUENAS NOTICIAS El calendario electoral ha seguido su curso. Las fechas para la consecución del proceso electoral federativo se han cumplido. Antes de que la Real Federación Española de Fútbol inicie su transcurso electoral en el último trimestre del año, muchas de Número 33 las Federaciones Autonómicas habremos finalizado con nuestras elecciones. Son buenas noticias. Julio editorial La Federación de Castilla y León tiene ya asam- de 2008 blea general y su comisión delegada, presidente y junta directiva para los próximos cuatro años de trabajo. La gestión que bajo mi directiva se pro- longará en este nuevo periodo olímpico estará marcada por la continuidad en los valores y acti- • NUMANCIA, EQUIPO DE 4 tudes definidos hasta ahora. PRIMERA La unidad con la que ha vivido el fútbol regional los meses electorales demuestra, una vez más, el grado de consenso existente. Aunque, por supues- to, no debe ser ésta razón para permanecer estan- cados sino para estimularnos en el trabajo diario. • MARCELINO MATÉ, 8 Esta Federación aún debe dar más de sí y será REELEGIDO PRESIDENTE ese nuestro empeño. Aunque haya transcurrido casi un mes desde el importantísimo logro deportivo para la Selección Nacional, no puedo dejar de felicitar a quienes lo • MIGUEL DE MENA Y hicieron posible y sentirme, como tantos otros, GUERRERO ALONSO 12 enormemente identificado con el júbilo vivido esos días en Austria y Suiza. -

European Qualifiers

EUROPEAN QUALIFIERS - 2014/16 SEASON MATCH PRESS KITS Ernst-Happel-Stadion - Vienna Saturday 15 November 2014 18.00CET (18.00 local time) Austria Group G - Matchday -9 Russia Last updated 12/07/2021 15:38CET Official Partners of UEFA EURO 2020 Previous meetings 2 Match background 3 Squad list 4 Head coach 6 Match officials 7 Competition facts 8 Match-by-match lineups 9 Team facts 11 Legend 13 1 Austria - Russia Saturday 15 November 2014 - 18.00CET (18.00 local time) Match press kit Ernst-Happel-Stadion, Vienna Previous meetings Head to Head FIFA World Cup Stage Date Match Result Venue Goalscorers reached 06/09/1989 QR (GS) Austria - USSR 0-0 Vienna Mykhailychenko 47, 19/10/1988 QR (GS) USSR - Austria 2-0 Kyiv Zavarov 68 1968 UEFA European Championship Stage Date Match Result Venue Goalscorers reached Austria - USSR Football 15/10/1967 PR (GS) 1-0 Vienna Grausam 50 Federation Malofeev 25, Byshovets 36, USSR Football Federation - 11/06/1967 PR (GS) 4-3 Moscow Chislenko 43, Austria Streltsov 80; Hof 38, Wolny 54, Siber 71 FIFA World Cup Stage Date Match Result Venue Goalscorers reached 11/06/1958 GS-FT USSR - Austria 2-0 Boras Ilyin 15, Ivanov 63 Final Qualifying Total tournament Home Away Pld W D L Pld W D L Pld W D L Pld W D L GF GA EURO Austria 1 1 0 0 1 0 0 1 - - - - 2 1 0 1 4 4 Russia 1 1 0 0 1 0 0 1 - - - - 2 1 0 1 4 4 FIFA* Austria 1 0 1 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 1 3 0 1 2 0 4 Russia 1 1 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 1 0 0 3 2 1 0 4 0 Friendlies Austria - - - - - - - - - - - - 11 3 3 5 9 14 Russia - - - - - - - - - - - - 11 5 3 3 14 9 Total Austria 2 1 1 0 2 0 0 2 1 0 0 1 16 4 4 8 13 22 Russia 2 2 0 0 2 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 16 8 4 4 22 13 * FIFA World Cup/FIFA Confederations Cup 2 Austria - Russia Saturday 15 November 2014 - 18.00CET (18.00 local time) Match press kit Ernst-Happel-Stadion, Vienna Match background Austria are taking on Russia for the first time since the end of the Soviet Union in UEFA EURO 2016 qualifying Group G, having failed to score in two previous friendly encounters. -

Designer Handbags, Watches, Shoes, Clothing & More

Michael Kors: Designer handbags, clothing, watches, shoes, and more--Shop Michael Kors for jet set luxury: designer handbags, watches, shoes, clothing & more. Receive free shipping and returns on your purchase.real jordans for cheap prices - FindSimilar.com Search results--real jordans for cheap prices - FindSimilar.com Search results The feather-pattern neckline striping can be clearly have you heard throughout the 'arena green' on going to be the Seahawks' new another one jerseys. (Seahawks image) The betting lines as what's all around the the Seahawks' new a completely new one pants. (Seahawks image) Marshawn Lynch shows having to do with the Seahawks' new violet home uniform,NCAA team jerseys,unveiled Tuesday on the basis of Nike. (Seahawks image) The many of the new a replacement uniform. (Seahawks image) Marshawn Lynch shows off going to be the Seahawks' many of the new white away uniform. (Seahawks image) The new away uniform. (Seahawks image) Marshawn Lynch shows ly the Seahawks' new gray alternate uniform. The fresh paint is always called wolf gray." (Seahawks image) The new gray alternate uniform. (Seahawks image) A blue jersey, white pants combo. (Seahawks image) A white jersey,glowing blue pants combo. (Seahawks image) A red jersey, gray pants combo. (Seahawks image) A gray jersey,custom football jersey,red pants combo. (Seahawks image) A white jersey, gray pants combo. (Seahawks image) A gray jersey, white pants combo. (Seahawks image) The many of the new Nike mittens show the modernized Seahawks logo allowing you to have