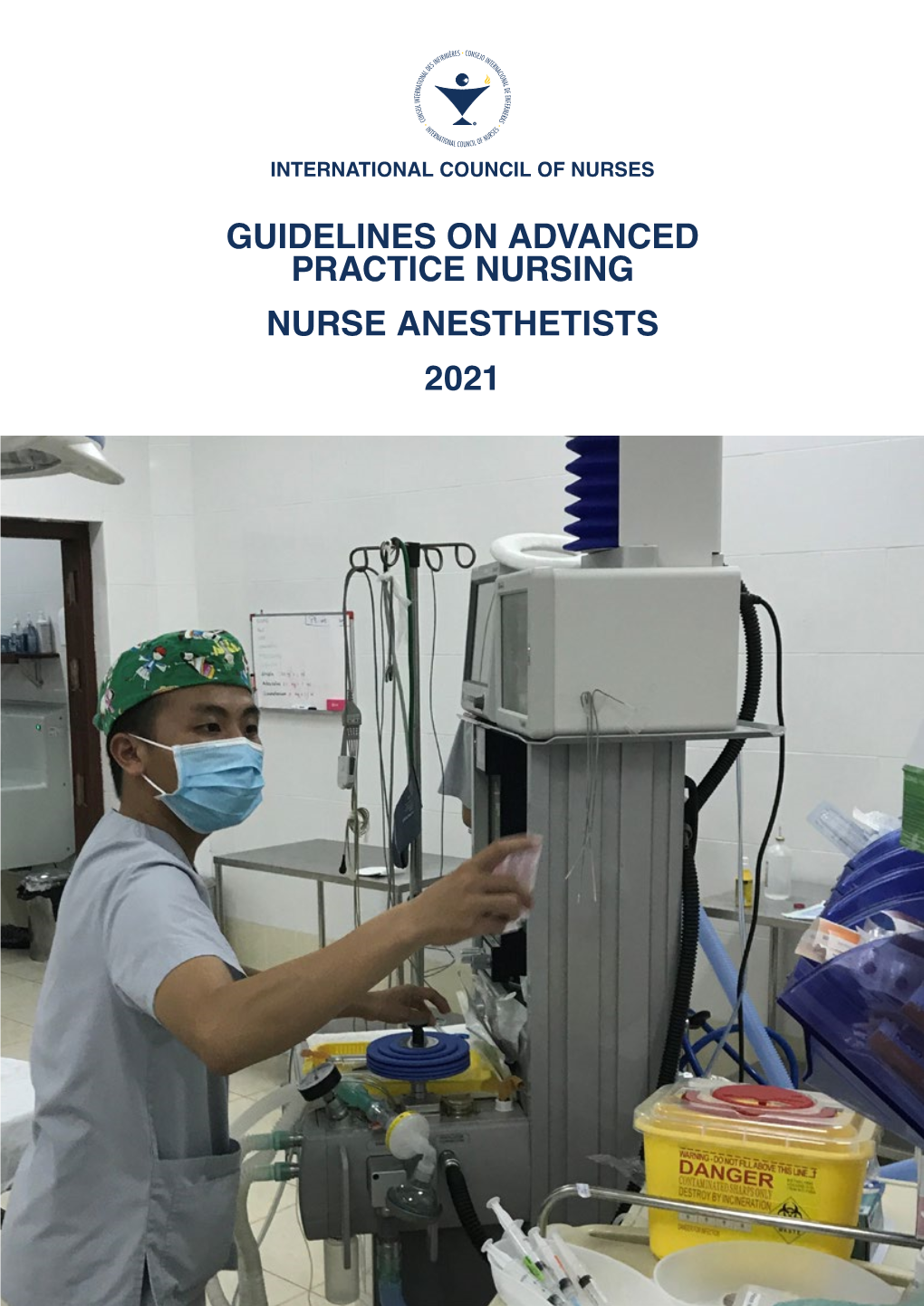

Guidelines for Nurse Anesthetists

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nursing Specialization in the UAE

Nursing Specialization in the UAE Specialization Committee Prepared by : Michelle Machon, RN, MSN Presented by: Aysha Al Mehri, RN Nursing Specialization Specialization refers to “the acquisition of a level of knowledge and skill in a particular area of nursing/ patient population which is greater than that acquired during the course of basic nursing education” (ICN, 2009) Levels of Specialty Description Education Qualification A nurse with experience in a certain area of No formal RN nursing who is recognized by the employer or education licensing authority as “specialized” in the field. Specialty specific certificate short courses e.g. one month RN wound care course Specialty nurses without general RN training (e.g. 3 year “direct RN pediatrics, psychiatry, etc.) entry” degree Post RN graduate specialty programs focusing on a 12-18 month post- Specialty RN patient population (e.g. peds, critical care, etc.) graduate diploma Specialized in a specific patient Masters level Specialty RN or population/disease process (e.g. Cardiology or program Advanced Neurosurgery Clinical Nurse Specialist) or in a Practice RN functional field of nursing (quality, education etc) “Advanced practice” nurse training resulting in Masters or PhD Advanced autonomous practitioners (Nurse level Practice RN Practitioner/Nurse Anesthetist). Possible Specialties worldwide 200 + including: Hyperbaric nursing Perioperative nursing Immunology and allergy nursing Private duty nursing Ambulatory care nursing Intravenous therapy nursing Psychiatric or mental health nursing -

Nurses: Are You Ready for Your New Role in Health Information Technology?

Nurses: Are You Ready for Your New Role in Health Information Technology? A 4-Part Educational Series Sponsored by TNA and TONE For 300,000 Texas Nurses Acknowledgement: Contribution by Susan McBride, PhD, RN and Mary Beth Mitchell, MSN, RN, BC-NI and the TNA/TONE HIT Task Force members © Texas Nurses Association, 2012 Webinar 4 Unintended Consequences of Using Electronic Health Records Mary Beth Mitchell, MSN, RN, BC Texas Health Resources Mari Tietze, PhD, RN, BC, FHIMSS Texas Woman’s University Introduction TNA/TONE Health IT Task Force • Charge: Determine implications of health care informatics for nursing practice and education in Texas • Include nationally-based Technology Informatics Guiding Education Reform (TIGER) initiative Vision: To enable nurses and interprofessional colleagues to use informatics and emerging technologies to make healthcare safer, more effective, efficient, patient-centered, timely and equitable by interweaving evidence and technology seamlessly into practice, education and research fostering a learning healthcare system. TNA = Texas Nurses Association http://www.thetigerinitiative.org/ TONE = Texas Organization of Nurse Executives 3 Introduction HIT Taskforce Membership Composed of TNA and TONE Members from practice and academia Task Force Members Texas Nurses Assoc. – David Burnett – Clair Jordan – Nancy Crider * – Joyce Cunningham – Mary Anne Hanley – Laura Lerma – Susan McBride – Molly McNamara – Mary Beth Mitchell – Elizabeth Sjoberg – Mari Tietze * * = Co-chairs 4 Why Does HIT Matter Introduction Environmental Forces: Deep in the Heart of • Health Care Reform/ARRA • Advanced Practice Nurse Roles Texas ? • EHR Incentives • IOM/RWJF Report Advancing Health Care • Informatics Nurse Standards by ANA Benchmark Reports on Progress CNE for Practicing Nurses Educational Content Dissemination Awareness Campaign HIT Orgs. -

Statement Comparing Anesthesiologist Assistant

STATEMENT COMPARING ANESTHESIOLOGIST ASSISTANT AND NURSE ANESTHETIST EDUCATION AND PRACTICE Committee of Origin: Anesthesia Care Team (Approved by the ASA House of Delegates on October 17, 2007, and last amended on October 17, 2012) Anesthesiologist Assistants (AA) and nurse anesthetists are both non-physician members of the Anesthesia Care Team. Their role in patient care is described in the American Society of Anesthesiologists' (ASA) Statement on the Anesthesia Care Team. The ASA document entitled Recommended Scope of Practice of Nurse Anesthetists and Anesthesiologist Assistants further details the safe limits of clinical practice. These documents state ASA's view that both AAs and anesthesia nurses have identical patient care responsibilities and technical capabilities--a view in harmony with their equivalent treatment under the Medicare Program. The proven safety of the anesthesia care team approach to anesthesia with either anesthesia nurses or AAs as the non-physician anesthetists confirms the wisdom of this view. Nevertheless, certain differences do exist between AAs and anesthesia nurses in regard to educational program prerequisites, instruction, and requirements for supervised clinical practice. Some of these differences are mischaracterized and misrepresented for the benefit of one category of provider over the other. The question that must be addressed is whether these differences in education and practice indicate superiority of one category of provider over the other in either innate ability or clinical capability. Historical Background of Nurse Anesthetists and Anesthesiologist Assistants- The Nurse Anesthesia discipline developed in the late 1800s and early 1900s out of surgeons' requests for more anesthesia providers since few physicians focused on anesthesia at that time. -

Preventive Health Care

PREVENTIVE HEALTH CARE DANA BARTLETT, BSN, MSN, MA, CSPI Dana Bartlett is a professional nurse and author. His clinical experience includes 16 years of ICU and ER experience and over 20 years of as a poison control center information specialist. Dana has published numerous CE and journal articles, written NCLEX material, written textbook chapters, and done editing and reviewing for publishers such as Elsevire, Lippincott, and Thieme. He has written widely on the subject of toxicology and was recently named a contributing editor, toxicology section, for Critical Care Nurse journal. He is currently employed at the Connecticut Poison Control Center and is actively involved in lecturing and mentoring nurses, emergency medical residents and pharmacy students. ABSTRACT Screening is an effective method for detecting and preventing acute and chronic diseases. In the United States healthcare tends to be provided after someone has become unwell and medical attention is sought. Poor health habits play a large part in the pathogenesis and progression of many common, chronic diseases. Conversely, healthy habits are very effective at preventing many diseases. The common causes of chronic disease and prevention are discussed with a primary focus on the role of health professionals to provide preventive healthcare and to educate patients to recognize risk factors and to avoid a chronic disease. nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com 1 Policy Statement This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the policies of NurseCe4Less.com and the continuing nursing education requirements of the American Nurses Credentialing Center's Commission on Accreditation for registered nurses. It is the policy of NurseCe4Less.com to ensure objectivity, transparency, and best practice in clinical education for all continuing nursing education (CNE) activities. -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Engineering Research, volume 205 Proceedings of the 3rd Green Development International Conference (GDIC 2020) The Development of Information Systems in Documentation Management of Critical Care Nursing Fadliyana Ekawaty1*, Dini Rudini2 1Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universitas Jambi 2Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Universitas Jambi *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Intensive Care Unit (ICU) is one of the units in the hospital that clients receive intensive medical care and monitoring. There, nurses carry out the nursing care process. All steps in the process must be properly documented. Although nursing care documentation is very important for both patients and nurses, but in reality there are still many incomplete nursing care documentations. The nurses’ awareness to completely fill the documents is still lack. Currently, many technological developments have been developed to support activities/work in various fields. one of them is the development of health information system, a nursing management system. So, this research aims to produce a product in the form of ICU nursing care documentation software that enable nurses in documenting their nursing care easier and well documented. The method used at this research is a product-oriented development model. The stages are: 1). Initiation System (initiation of the system), 2). Analysis System, 3). Design System and 4). Production that then tested through the prototype Black Box Testing. The research result shows that this software very useful because it shortens the time for preparing reports. Even this study uses students as research objects, nurses who work in the hospital also can use this software. -

Empowering Frontline Staff to Deliver Evidence-Based Care

Empowering frontline staff to deliver evidence-based care: The contribution of nurses in advanced practice roles Executive summary Kate Gerrish, Louise Guillaume, Marilyn Kirshbaum, Ann McDonnell, Mike Nolan, Susan Read, Angela Tod This Executive Summary presents the main findings from a major research study examining the contribution of advanced practice nurses1 (APNs) to promoting evidence-based practice among frontline staff. The study was commissioned by the Department of Health as part of its Policy Research Programme. Background The need for frontline staff to be empowered to deliver a quality service is a major aspect of contemporary healthcare policy.Within the nursing professions this has been supported by the introduction of new advanced practice roles such as consultant nurse and modern matron, to augment the existing clinical nurse specialist, nurse practitioner and practice development nurse roles. Policy guidance on advanced practice roles identifies the need for nurses in such positions to base not only their own practice on research evidence, but also through clinical leadership to act as change agents in promoting evidence-based care amongst frontline staff. Despite widespread recognition of the need for nursing practice to be based on sound evidence, frontline staff experience considerable challenges to implementing evidence-based care at an individual and organisational level. In particular, frontline nurses have difficulty interpreting research findings and although willing to use research they often lack the skills to do so. A lack of organisational support in the form of unsupportive colleagues and restricted local access to information is also problematic (Bryar et al 2003). Research examining evidence-based practice identifies the contribution that ‘opinion leaders’ such as advanced practice nurses make in influencing the practice of frontline staff (Fitzgerald et al 2003). -

Briefing Slides — Expanding the Role

Welcome! Briefing — Expanding the Role of Nurse Practitioners May 6, 2019 12:00 PM Expanding the Role of Nurse Practitioners Sandra Shewry, MPH, MSW Vice President, External Engagement Future Health Workforce Commission Independent one-year effort to develop and prioritize recommendations to meet California’s health care needs over the next 10 years. Recommendation 3.1 includes: (1) Expanding NP education to increase supply in underserved communities (2) Maximizing use of NP skills within current regulations (3) Giving NPs full practice authority after a transitional period of collaboration with a physician or experienced NP Full practice authority: Practicing and prescribing without physician supervision 28 states + DC allow NPs to have full practice authority No full practice authority Full practice authority upon licensure Full practice authority after transitional period Expanding the Role of Nurse Practitioners Joanne Spetz, PhD, Healthforce Center at UCSF Elizabeth Holguin, PhD, MPH, MSN, FNP-BC, Presbyterian Healthcare Services, New Mexico Tillman Farley, MD, Salud Family Health Centers, Colorado Susan VanBeuge, DNP, APRN, FNP-BC, University of Nevada School of Nursing, Nevada NPs are one of several types of advanced practice registered nurses • Advanced practice registered nurses (APRNs): – Nurse practitioners – Nurse-midwives – Nurse anesthetists – Clinical nurse specialists • Master’s or doctoral education, substantial clinical training • Education includes pharmacology and other content needed for safe prescribing of medications • Some states license NPs as APRNs and specify NP roles within their nurse practice act Most NPs are in primary care fields Educational focus of California’s NPs, 2017 100% 90% 80% 70% 62.8% 60% 50% 40% 30% 24.6% 20% 16.2% 15.8% 13.6% 9.7% 7.8% 10% 3.0% 2.9% 2.2% 0% Source: Spetz, J, Blash, L, Jura, M, Chu, L. -

Letter from ANA to the Office of National Coordinator for Health IT

November 6, 2015 Karen DeSalvo, MD, MPH, MSc National Coordinator Office of National Coordinator for Health IT Department of Health and Human Services 200 Independence Ave, SW Washington, DC 20201 Re: Comments on 2016 Interoperability Standards Advisory Best Available Standards and Implementation Specifications Submitted via: https://www.healthit.gov/standards-advisory/2016 Dear Dr. DeSalvo: The American Nurses Association (ANA) welcomes the opportunity to provide comments on the document “2016 Interoperability Standards Advisory Best Available Standards and Implementation Specifications.” As the only full-service professional organization representing the interests of the nation’s 3.4 million registered nurses (RNs), ANA is privileged to speak on behalf of its state and constituent member associations, organizational affiliates, and individual members. RNs serve in multiple direct care, care coordination, and administrative leadership roles, across the full spectrum of health care settings. RNs provide and coordinate patient care, educate patients, their families and other caregivers as well as the public about various health conditions, wellness, and prevention, and provide advice and emotional support to patients and their family members. ANA members also include the four advanced practice registered nurse (APRN) roles: nurse practitioners, clinical nurse specialists, certified nurse-midwives and certified registered nurse anesthetists.1 We appreciate the efforts of the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology -

History of Midwifery in the US Parkland Memorial Hospital

History of Midwifery in the US Parkland Memorial Hospital Parkland School of Nurse Midwifery History of Midwifery in the US [Download this file in Text Format] Midwifery in the United States Native Americans had midwives within their various tribes. Midwifery in Colonial America began as an extension of European practices. It was noted that Brigit Lee Fuller attended three births on the Mayflower. Midwives filled a clear, important role in the colonies, one that Laurel Thatcher Ulrich explored in her Pulitzer Prize winning book: A Midwife's Tale: The Life of Martha Ballard Based on Her Diary 1785-1812. (Published in 1990). Midwifery was seen as a respectable profession, even warranting priority on ferry boats to the Colony of Massachusetts. Well skilled practitioners were actively sought by women. However, the apprentice model of training still predominated. A few private tutoring courses such as those offered by Dr. William Shippman, Jr. of Philadelphia existed, but were rare. The Midwifery Controversy The scientific nature of the nineteenth century education enabled an expansive knowledge explosion to occur in medical schools. The formalized medical communities and universities not only facilitated scientific inquiry, but also communicated new information on a variety of subjects including Pasteur's theory of infectious diseases, Holmes' and Semmelweis' work on puerperal fever, and Lister's writings on antisepsis. Since midwifery practice generally remained on an informal level, knowledge of this sophistication was not disseminated within the midwifery profession. Indeed, medical advances in pharmacology, hygiene and other practices were implemented routinely in obstetrics, without integration into midwifery practices. The homeopathic remedies and traditions practiced by generations of midwives began to appear in stark contrast to more "modern" remedies suggested by physicians. -

Tele Critical Care Implementation and Education Project

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Master's Projects and Capstones Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects Summer 8-5-2020 Tele Critical Care Implementation and Education Project Jeffrey Dover [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone Part of the Critical Care Nursing Commons, and the Telemedicine Commons Recommended Citation Dover, Jeffrey, "Tele Critical Care Implementation and Education Project" (2020). Master's Projects and Capstones. 1059. https://repository.usfca.edu/capstone/1059 This Project/Capstone is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Projects and Capstones by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TCC IMPLEMENTATION & EDUCATION PROJECT 1 Practicum Prospectus: Tele Critical Care Implementation and Education Project Jeffrey Dover University of San Francisco TCC IMPLEMENTATION & EDUCATION PROJECT 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Section I: Title and Abstract Title ........................................................................................................................... 1 Abstract .................................................................................................................... -

JNR0120SE Globalprofile.Pdf

JOURNAL OF NURSING REGULATION VOLUME 10 · SPECIAL ISSUE · JANUARY 2020 THE OFFICIAL JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL COUNCIL OF STATE BOARDS OF NURSING JOURNAL Volume 10 Volume OF • Special Issue Issue Special NURSING • January 2020 January REGULATION Advancing Nursing Excellence for Public Protection A Global Profile of Nursing Regulation, Education, and Practice National Council of State Boards of Nursing Pages 1–116 Pages JOURNAL OFNURSING REGULATION Official publication of the National Council of State Boards of Nursing Editor-in-Chief Editorial Advisory Board Maryann Alexander, PhD, RN, FAAN Mohammed Arsiwala, MD MT Meadows, DNP, RN, MS, MBA Chief Officer, Nursing Regulation President Director of Professional Practice, AONE National Council of State Boards of Nursing Michigan Urgent Care Executive Director, AONE Foundation Chicago, Illinois Livonia, Michigan Chicago, Illinois Chief Executive Officer Kathy Bettinardi-Angres, Paula R. Meyer, MSN, RN David C. Benton, RGN, PhD, FFNF, FRCN, APN-BC, MS, RN, CADC Executive Director FAAN Professional Assessment Coordinator, Washington State Department of Research Editors Positive Sobriety Institute Health Nursing Care Quality Allison Squires, PhD, RN, FAAN Adjunct Faculty, Rush University Assurance Commission Brendan Martin, PhD Department of Nursing Olympia, Washington Chicago, Illinois NCSBN Board of Directors Barbara Morvant, MN, RN President Shirley A. Brekken, MS, RN, FAAN Regulatory Policy Consultant Julia George, MSN, RN, FRE Executive Director Baton Rouge, Louisiana President-elect Minnesota Board of Nursing Jim Cleghorn, MA Minneapolis, Minnesota Ann L. O’Sullivan, PhD, CRNP, FAAN Treasurer Professor of Primary Care Nursing Adrian Guerrero, CPM Nancy J. Brent, MS, JD, RN Dr. Hildegarde Reynolds Endowed Term Area I Director Attorney At Law Professor of Primary Care Nursing Cynthia LaBonde, MN, RN Wilmette, Illinois University of Pennsylvania Area II Director Philadelphia, Pennsylvania Lori Scheidt, MBA-HCM Sean Clarke, RN, PhD, FAAN Area III Director Executive Vice Dean and Professor Pamela J. -

Health Information Technology Basics Institute for Health & Socio-Economic Policy

Health Information Technology Basics Institute for Health & Socio-Economic Policy © Copyright IHSP 2009. All rights reserved. Table of Contents Part I Introduction 1 Part II Why Workplace Technologies Change 2 Section 1: Overview 2 Section 2: Confl icting Values 2 Section 3: Management Secrets 3 Part III Routinizing Patient Care 8 Section 1: Overview 8 Section 2: The Core Technologies 9 Section 3: Supplemental Technologies 17 Part IV Nursing Values and Resistance 19 I FOR CNA/NNOC Part I Introduction Health information technology (HIT) is widely celebrated as a universal healthcare fix. Promoters say it will contain costs, improve quality, and modernize medical care. But such promises are the public relations messages of the HIT and healthcare industries. Is HIT really the panacea to cure our healthcare crisis, or are there consequences that aren’t being discussed? RNs have good reason to be wary. Patient care processes in some hospitals have already been transformed by HIT, and many other hospitals will be adopting it in the next few years. Among other types, hospitals are adopting • electronic medical records, • clinical decision support systems, • e-prescribing, • medication dispensing, • radio frequency identification and tracking, • medical credit scoring, • telemedicine, and • robots. Clinical decision support systems (CDSS) are one widespread technology that affects patient care directly. Of the 5,139 U.S. hospitals reporting (almost all hospitals not run by the federal government), 67.6% have adopted fully automated CDSS and 8% have either begun the installation process or have contracted to do so. A revolution is well underway. It will soon reach RNs and patients in every hospital.